Introduction

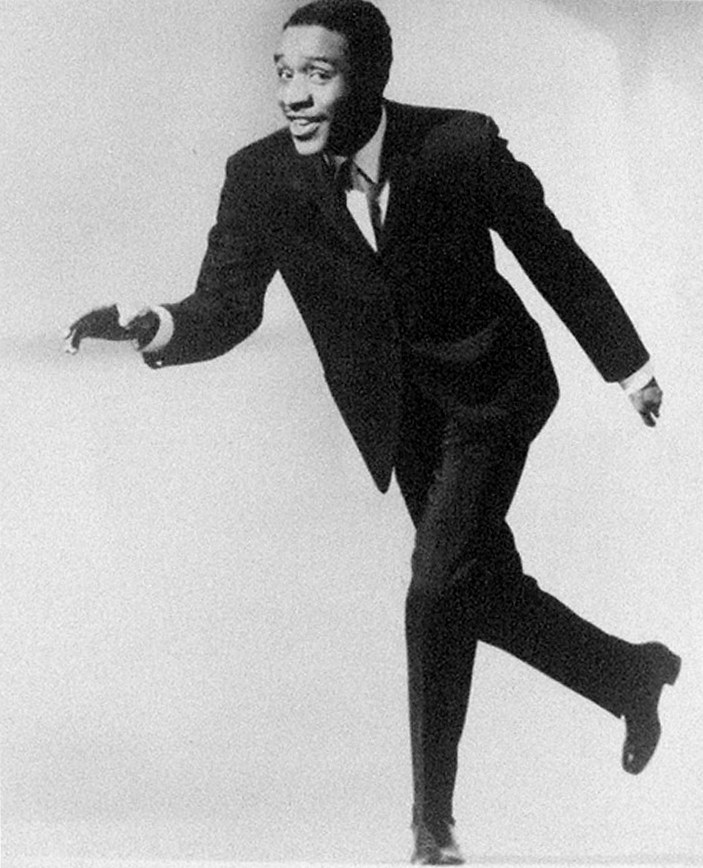

Very few ballet and modern dancers perform into their sixties. Tap dancers are a different breed. At his Jacob’s Pillow debut in 1996, Jimmy Slyde was almost seventy. He jokingly labeled his solo spot “Senior Citizens’ Time” but there was nothing superannuated about his performance, nothing broken-down in the least. Instead, the advanced age of the dancer seemed something to boast about, like the age of a whiskey—a sign of maturation and the richness resulting from processes that take decades:

The sliding could be a gimmick, but Slyde makes it into an entire expressive idiom, with slides of different kinds and sizes functioning like different parts of speech.His name announces his trademark locomotion, the spelling signals his attitude: as laid-back as a lowercase y. The sliding could be a gimmick, but Slyde makes it into an entire expressive idiom, with slides of different kinds and sizes functioning like different parts of speech. The slides are visually compelling, the magical beauty of the horizontal flow compounded by the way Slyde’s thin figure tilts and twists and glides, his knees flexing and compressing like a skier’s. But the slides, though silent, are equally musical. They’re dancing rests that Slyde uses to anticipate the beat and suspend it, to fall behind and to catch up. Their speeding and slowing suggests crescendos and diminuendos; their stretch implies sustained notes, slurred sounds, breath. The slides are integral to Slyde’s percussive music: his bebop phrasing, his swing, his aural pithiness, his wit. They connect and complete the rest of his vocabulary, setting up and amplifying the spins and spurts and hepcat poses. He always stressed that slides could not be controlled exactly. The factor of slippage—of chance—was inescapable, and this element of accident kept him and his audiences alert.

In the clip above, notice how he starts nice and easy, warming up along with his viewers. After a while, he opens the throttle a bit, testing out the floor and his body with some scoots but quickly pulling back. It’s a tease, a taste, just a glimpse of how he can make your eyes widen and your vision expand, especially if you’re not expecting an old guy to cover so much ground so quickly. There’s some magical-seeming relation between Slyde’s fluid command of gravity—weight, balance, friction, momentum—and his approach to aging. It feels miraculous when, between songs, he spreads out and the spotlight operator struggles to keep up. Near the end, he slips in a backslide, an old tap move that Michael Jackson made famous as the Moonwalk (below). This kind of cool never goes out of style.

As Slyde explains (below) in a post-show discussion after a 1998 Pillow performance, he thought the term “improvisation” was overused. He preferred the word “ad-libbing” to describe what he did: selecting from a vast mental library of steps, invented by him and those who came before him, in response to the music.

Slyde’s manner of speaking was often cryptic. He liked to communicate in metaphors, letting the lessons of dance resonate as lessons about life. “You run into uneven floors,” he would say, “nails sticking up, things that get in the way.” How to respond to such obstacles? “You’ve got to fall, and you’ve got to learn how to get up, gracefully. Like you never fell. Everybody slides sometimes.”

Learning to Get Up Gracefully

He was born James Titus Godbolt in 1927. When he was two years old, his family moved from Atlanta to Boston, and though he would later live for spells in California, New York, and Europe, he would always return to Boston. (He sometimes related his sliding to the slippery sidewalks of New England winters.) His father worked for the railroad. His mother loved theater and music. Dreaming of her boy becoming a concert violinist, she enrolled him in violin classes at the New England Conservatory of Music. He liked music, but he was also athletic and wanted to move around more. Fortunately, there was a solution, a way to make music while in motion. Across the street from the Conservatory stood the dancing school of Stanley Brown.

Brown had been a professional dancer himself, and he was friends with black show business royalty, men such as Bill Robinson and John Bubbles, who sometimes came by to teach. Most of the teachers at the studio were black, most of the students white. Tap was the core of the curriculum, as it still occupied the center of American entertainment, but there were also classes in ballet and acrobatics. The school’s recitals attracted talent scouts and agents. Brown was a stickler, a disciplinarian. (“He was a great shouter,” Slyde recalled.) “You’ll never become anything if you don’t practice,” he told the boy.

But this boy did practice. Starting classes at 12, he studied at Brown’s studio until he was 17 and one of the teachers, “Schoolboy” Eddie Ford, paired him with an age-mate named Jimmy Mitchell. The young duo tapped and did flips and slid through each other’s legs in the manner of the famous Nicholas Brothers, but they also specialized in Ford’s specialty: slides. They called themselves the Slyde Brothers, and when James Godbolt joined the performer’s union, he took the name Jimmy Slyde.

The act lasted only about a year, until Mitchell got drafted into the army. Slyde spent two years at Shaw University on a football scholarship, still dancing. He was small for football, but the problem he faced as a tap dancer was larger than himself. The world of show business that Brown trained students like Slyde to enter—revues, musicals, touring jazz bands, nightclubs that always hired tap dancers —that world was disappearing.

Slyde went on the burlesque circuit as “a novelty act,” touring to Chicago and the Midwest. In the late fifties, he moved to Los Angeles, hoping to break into movies. But Hollywood wasn’t interested in tap dancers anymore, especially not in tap dancers of his color. He found a job with a band now and then; sometimes the clubs paid only in food. When clubs started putting in carpeting—both a sign and a cause of tap’s fall from favor—he starting bringing along a little wooden board that didn’t give him much room to slide.

“Maybe that was one of my most creative times,” Slyde recalled, “because I was very angry. It made me want to be a better dancer to show them what they missed.” On the Los Angeles TV show Club Checkerboard in 1958 he briefly displayed to a larger audience what he meant: the footage stands as some of the very best and most original tap of that (or any) period. The show led to a gig with Bing Crosby’s golf tournament in Pebble Beach, a brush with celebrity that made Slyde hopeful, yet neither that job nor anything else led to steady work.

“I just felt that there had to be some room for tap dancing somewhere out there,” Slyde remembered thinking. “There’s room for everything else.” In 1966, George Wein, the influential impresario of the Newport Jazz Festival (which had featured tap dancers as popular novelties announced as a “dying breed” a few years earlier), included Slyde in a group of hoofers he brought to the Berlin Jazz Festival. With Baby Laurence, Buster Brown, and Chuck Green—all master tap dancers, a little older than Slyde—he joined an all-star swing-era band (Roy Eldridge, Illinois Jacquet, and Jo Jones, among others). In Germany, and then in France and Sweden and Switzerland, the dancers received huge ovations and respect as artists. Slyde assumed that lots of work for tap dancers on the thriving jazz festival circuit would follow. But it didn’t. He never forgave George Wein. (Years later, Wein explained that as much as he loved tap dancers, their names didn’t sell tickets.)

Something similar happened in 1969, when a group of hoofers including Slyde took over Monday nights at a seedy New York theater for a gathering called “Tap Happening.” Astonished reviewers and grateful audiences praised it as the best dance show in town, and it moved to another theater for a full run, seeming to herald a tap revival. And yet it, too, fell apart. Squabbles over money were at fault, but Slyde had grounds to blame other cultural forces for the perpetual sputtering of his career. With the skilled white tap dancer Ray Malone, and later with another named Jack Ackerman, Slyde practiced for months and months. But very few clubs in the 1960s wanted to hire an interracial team. The name of their act, “Just in Time,” was overly optimistic.

Europe still offered some hope. Slyde was filmed for the 1972 French documentary L’Aventure du Jazz, and he toured Europe as a live counterpart to the film. “I got such a different response,” Slyde recalled. “I shed all these layers that were starting to decay my thoughts about being an artist. I started breathing again.” In 1974, he recorded an album in Paris, tapping as the lead soloist of a jazz combo—an achievement that he felt could happen only in Europe. “The Europeans want to make up for the lack of respect that has been shown here,” he told Jerry Ames and Jim Siegelman for The Book of Tap (1977). Apart from frequent trips home to visit his mother, Slyde spent many years in France.

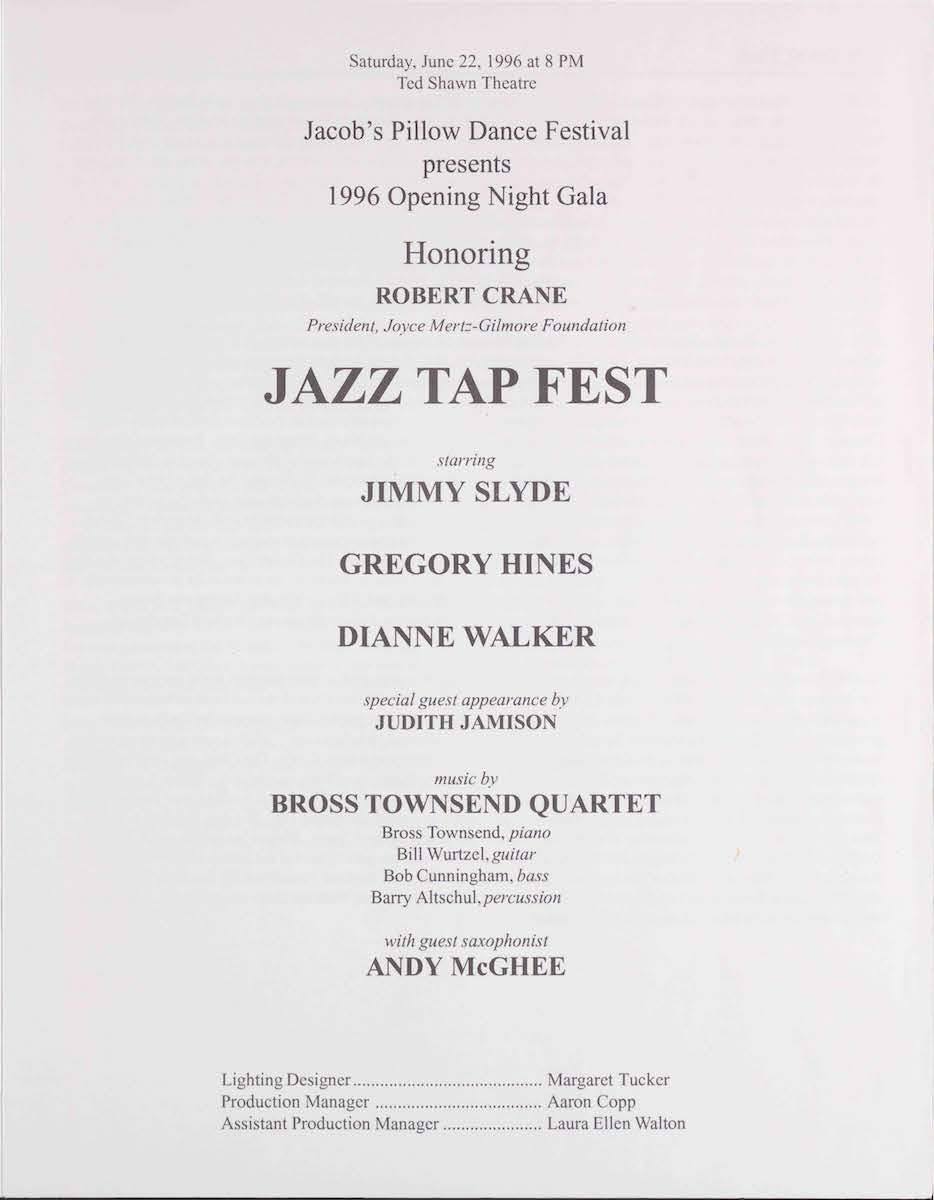

By the end of the 1970s, the long-awaited revival of tap in the United States was gaining momentum.By the end of the 1970s, though, the long-awaited revival of tap in the United States was gaining momentum. Tap companies such as Jazz Tap Ensemble were getting jazz tap into concert-dance venues (such as Jacob’s Pillow) and bringing the old masters along with them. Slyde toured with some of his “Tap Happening” buddies in the revue 1000 Years of Jazz, but he was also invited to perform at the Smithsonian Institution and featured in the film documentary About Tap. Tap now had a movie star in Gregory Hines, who pressed to give Slyde and other hoofers of his generation cameo appearances in the Hollywood movies The Cotton Club (1984) and Tap (1989). Slyde lit up his featured spot in the 1986 Paris revue Black and Blue (impressing the young Savion Glover, who was also in the cast). His dancing in the Broadway version (1989-1991) earned him a Tony Award nomination.

He was now a silver-haired elder statesman of tap, regularly celebrated at tap festivals and tap events. Though he rarely gave formal classes and didn’t think of himself as a teacher (he preferred the term “nudge”), he was an influential educator, offering help through gnomic comments and, most of all, by hosting jam sessions in the small Manhattan club La Cave, where young dancers could practice in public with a jazz band. The young participants came to consider themselves enrolled in “The University of La Cave.” Savion Glover, already commonly referred to as the future of tap, was Slyde’s most famous acolyte but far from the only one.

Slyding at the Pillow

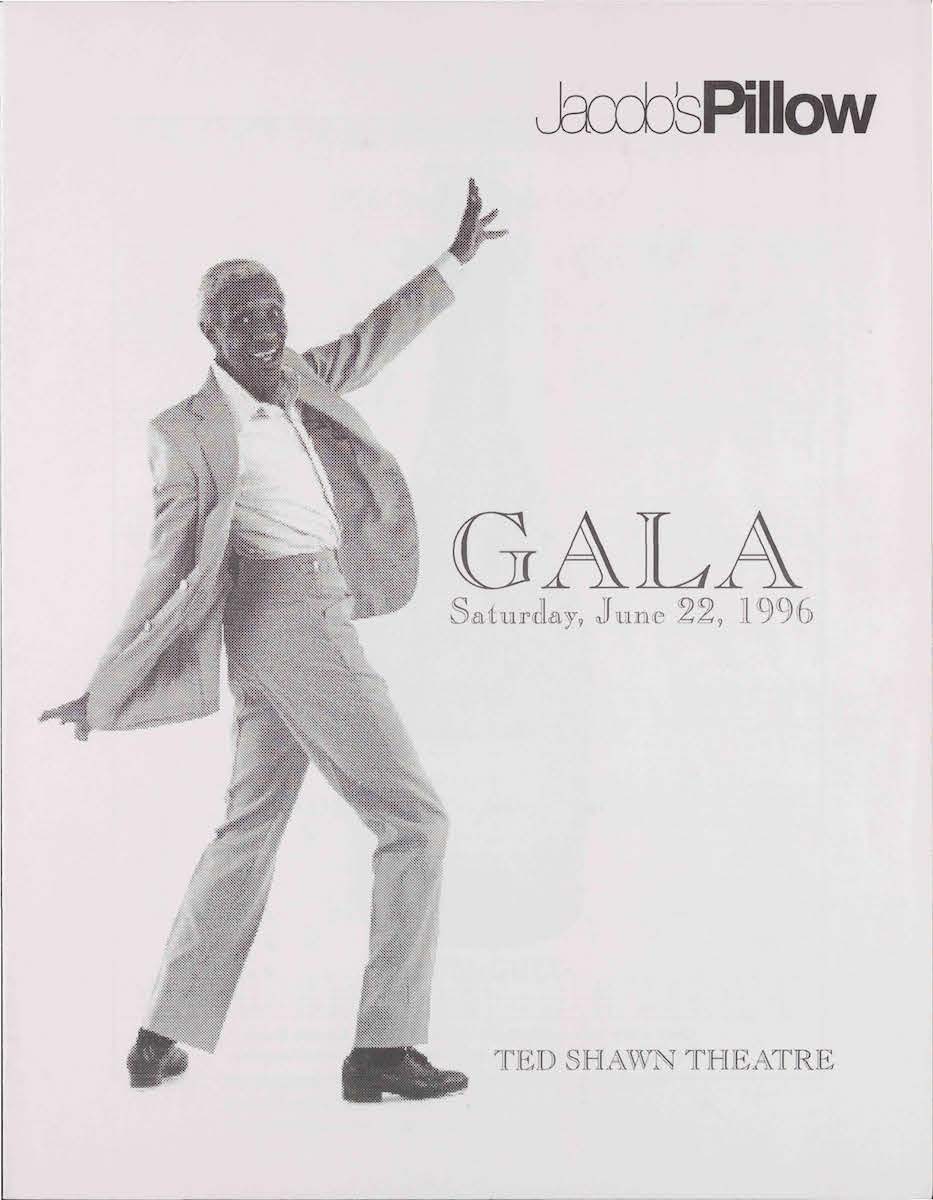

It was a group of these protégés that Slyde brought to Jacob’s Pillow in 1996, when he was invited to present a “Jazz Tap Fest” called “Jimmy Slyde and Friends.” Along with Slyde’s fellow Bostonian Dianne Walker, the lineup was stacked with La Cave regulars: Karen Callaway, Van Porter, Herbin Van Cayseele, and Max Pollak. The last two—born, respectively, in Guyana and Austria—were representatives of what Slyde called “the international language of tap.” (Both would return to the Pillow several times: Van Cayseele with “Hip Hop & Jazz Tap” and his own carnivalesque Urban Tap, Pollak with his Afro-Cuban tap ensemble RumbaTap.) As he often did at La Cave, Slyde called out the names of deceased tap dancers, some famous, some not, a litany he spoke of as “remembering.”

Just before Slyde returned to the Pillow in 1998 as a guest artist with Jazz Tap Ensemble, he fell and injured an arm. He watched the first night of the run from the audience. During the second night, he surprised viewers by walking onstage with one wrist in a brace, telling them, “Don’t laugh at me right away.” As he began dancing, he asked the audience if anyone recognized what he was doing: the signature steps of Steve Condos, a friend who had died of heart failure moments after a performance on a bill with Slyde in 1990. Slyde was now 71, the age at which Condos had died, and he was undoubtedly more fragile than he had been as a younger man. But his self-deprecation and oh-my-aching-back gestures were mostly for show. His dancing embodied no one’s idea of the degradations of age, though a viewer’s awareness of how easily an aging body can break heightened the sense of risk and increased the heroism of Slyde’s nonchalance. As Dianne Walker, who appears in the wings in the middle of the clip below, said afterward,

No matter how many times we see Slyde, it’s always like the first time.”

Sali Ann Kriegsman, the director of the Pillow from 1995 to 1997, established a Jazz Tap Residency Project that sent Walker and Slyde around the Berkshires to teach, perform, and lead workshops. One afternoon, Slyde and the pianist Bross Townsend were scheduled to do a short demonstration in a public park in Pittsfield for the residents of the public houses nearby.

“A stage had been set up,” Kriegsman recalled, “but just before the start the heavens opened and the performance had to be scratched. Jimmy was determined not to disappoint the few youngsters who had stayed behind. But the stage was soaked. [We] found a piece of plywood; it was laid down under a small tent that had been set up with refreshments. Jimmy proceeded to do a few steps, then turn to the kids and say ‘let’s see what you’ve got.’ We had to pry him away—it was a very nasty, chill, wet day and we were concerned about his health. This was Jimmy through and through.”

For Slyde’s next appearance at the Pillow, in 2005, he was again a guest, this time of Savion Glover. Since their days together in Black and Blue and at La Cave, Glover had honored Slyde in the hit Broadway show Bring in ‘da Noise/Bring in ‘da Funk and had brought him to the White House for a 1997 special that was broadcast on PBS. The Pillow program opened with a Hoofer’s Line, also known as The Track, a format in which dancers in a row keep up the beat as one by one they step out to make personal statements in percussion, responding to the statements of the others. It is an enactment of how tap is passed down, especially when the participants span multiple generations. That was true when a pubescent Glover joined the Hoofer’s Line with Slyde in Black and Blue, and it was true again at the Pillow when Slyde and Walker and Glover shared a Hoofer’s Line with the younger dancers Marshall Davis, Jr. and Cartier Williams:

Slyde’s introduction of his own solo, later in the show, as “stumbling and fumbling” was belied by his enduring mastery. Many of the signature steps he deploys in the footage of his 1996 Pillow performances recur in footage from 2005 (below), undiminished. His slides still seem to open the world up, to make it suddenly feel larger. But the special warmth of this clip arises from Glover, who watches Slyde smittenly, singing along and scatting to “Satin Doll.” The love and pride in Glover’s face cast a glow over the performance, one of Slyde’s last before his death less than three years later:

The Slyde Legacy

“They haven’t left us,” Slyde liked to say about dancers who had passed on. “They left something for us.” Well before Slyde was offstage for good, his influence could be sensed in his absence, when other dancers were on the boards. Most obviously, his style was suffused throughout the young disciples he brought to the Pillow for “Jimmy Slyde and Friends.” Most formally, his approach was packaged in the choreography for Jazz Tap Ensemble’s Interplay, a suite of solos, duets, and ensemble sections, all set to some of Slyde’s favorite songs. To create the piece, the company’s director, Lynn Dally, and the dancer Derick Grant traveled to Boston, where Slyde gave them some steps and ideas and left to play golf. What Dally and her dancers put together is a near-ideal balance of set choreography and patches of improvisation, one prompting the other. It’s a collection of steps created by the man whom the Ensemble member Sam Weber called “the most ripped-off dancer in tap dancing,” an encapsulation of his style, but it’s one that nurtures the styles of others:

A few years after Slyde’s death, Michelle Dorrance, just emerging as a major force in tap, choreographed a tribute to him called Remembering Jimmy. The choice of socks rather than tap shoes was partly a response to prohibitions against floor-scarring taps in many of the modern-dance venues that were starting to hire Dorrance’s company, but the footwear also imparted a ghostly hush that was appropriate for a work in memoriam. The time-stretching silences of slides, punctuated by soft thuds, resounded without accompaniment. Setting some of Slyde’s steps and phrases in counterpoint with one another, Dorrance created a ritual for dancers in white, captured below in Dorrance Dance’s 2011 Pillow debut:

Most recently, in 2016, a tap show commissioned by the Pillow took its title and its ethos from one of Slyde’s remarks. Explaining the difficulty of tap in the 1985 documentary About Tap, Slyde said,

There’s balance involved, there’s movement involved, and still you must swing.”

Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, who had performed with Slyde as a teenager in the Broadway production of Black and Blue, fixed on the quote as a truth she felt was in danger of being lost as young tap dancers concentrated too much on technical advancement, missing music and soul.

And Still You Must Swing, the show she created with Derick Grant and Jason Samuels Smith, two peers as well versed in tradition as she was and as cutting-edge, abounded in tap that was extraordinarily complex without sacrificing swing. It channeled some of Slyde’s sublimated anger and more of his joy. It echoed with allusions to him and other departed masters. And among its implied messages was this: as long as such dancing persists, Slyde’s spirit still swings.

PUBLISHED July 2017