Silent Beginnings: the Shawn Years

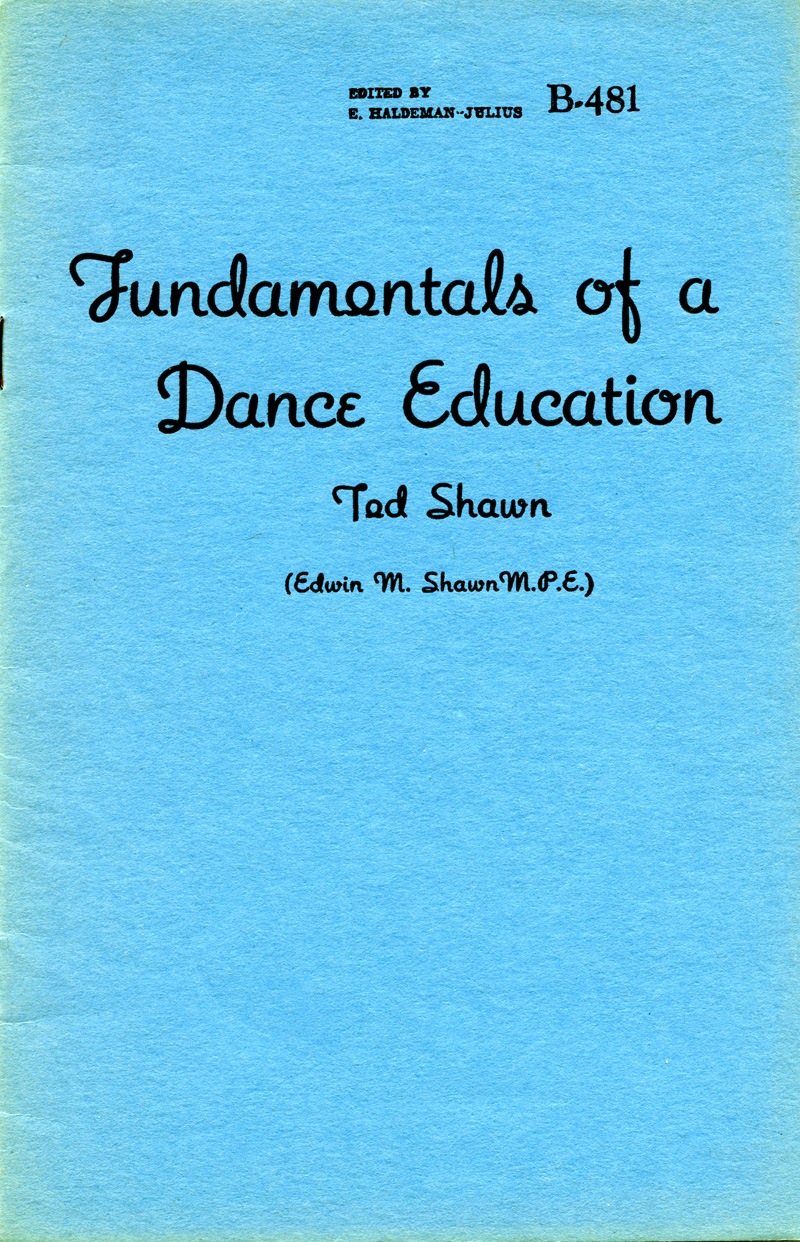

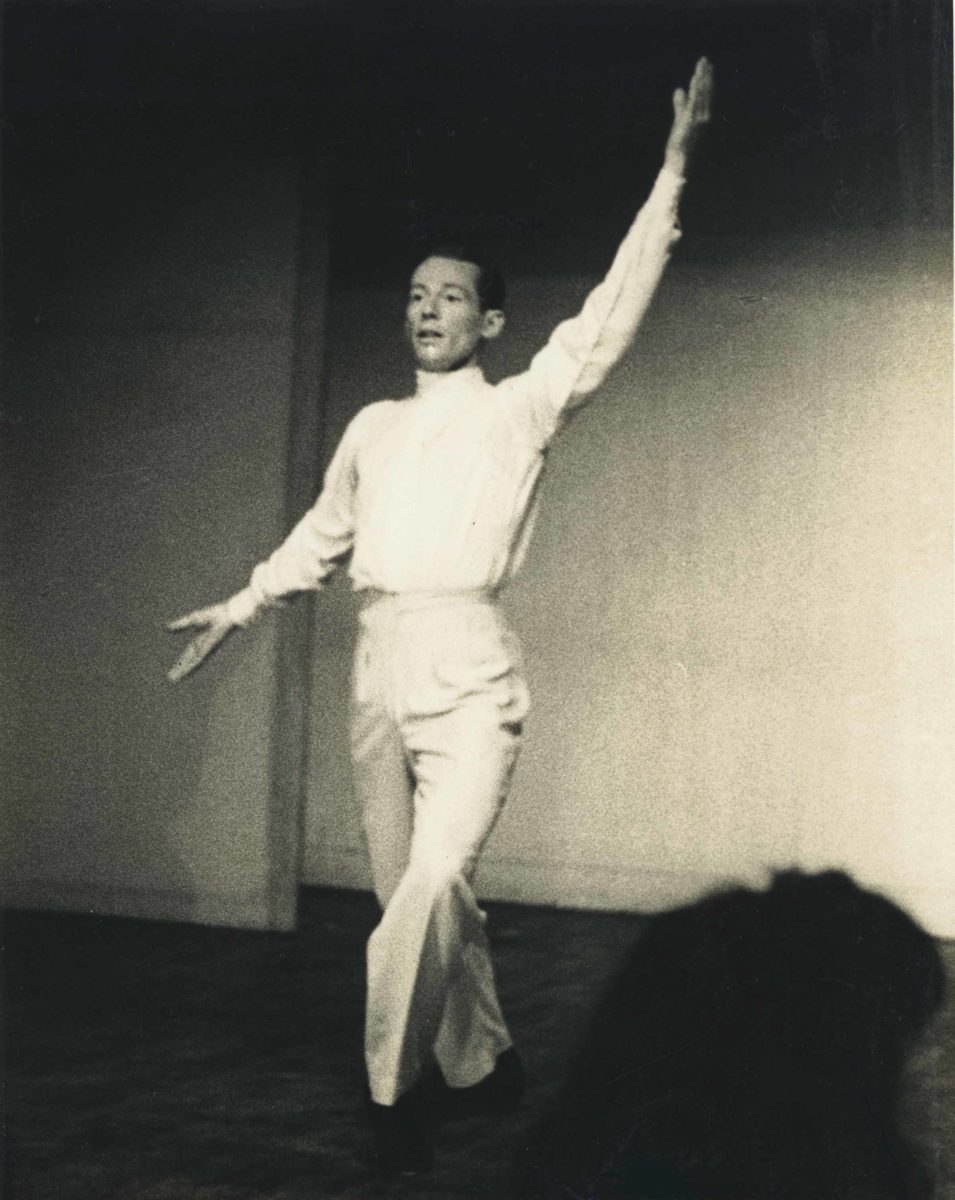

During the lifetime of Ted Shawn, the sounds of tap dancing were heard at Jacob’s Pillow almost never. This was no accident or oversight. Shawn held systematically developed views about every kind of dance, and he was far from shy about asserting them. In his 1937 book Fundamentals of a Dance Education, he railed against tap as “an invention of the devil.”

If Shawn believed that tap was “the scourge of the dance world today,” that was partly because tap was very popular in 1937. Fundamentals of a Dance Education was broadminded in its insistence that an educated dancer know many kinds of dance. Tap was the most common one in Hollywood musicals—in addition to vaudeville, Broadway musicals, nightclubs, and the shows of touring jazz bands. Shawn felt that this commercial popularity pushed out other forms, creating “standardization” and “destroying the taste for better things.”

So far, so reasonable. Yet “better things” is telling. In Shawn’s view, tap wasn’t art; it was “movement without significance,” a mere “dexterity of the feet.” The most grudging value he could give it was as “a cheap form of entertainment.” This snobbery yielded blindness and deafness: Shawn couldn’t hear jazz as music, either. He had to explain away the appeal of Fred Astaire as a matter of mere personality and of Astaire’s supposed (but actually minimal) training in classical ballet.

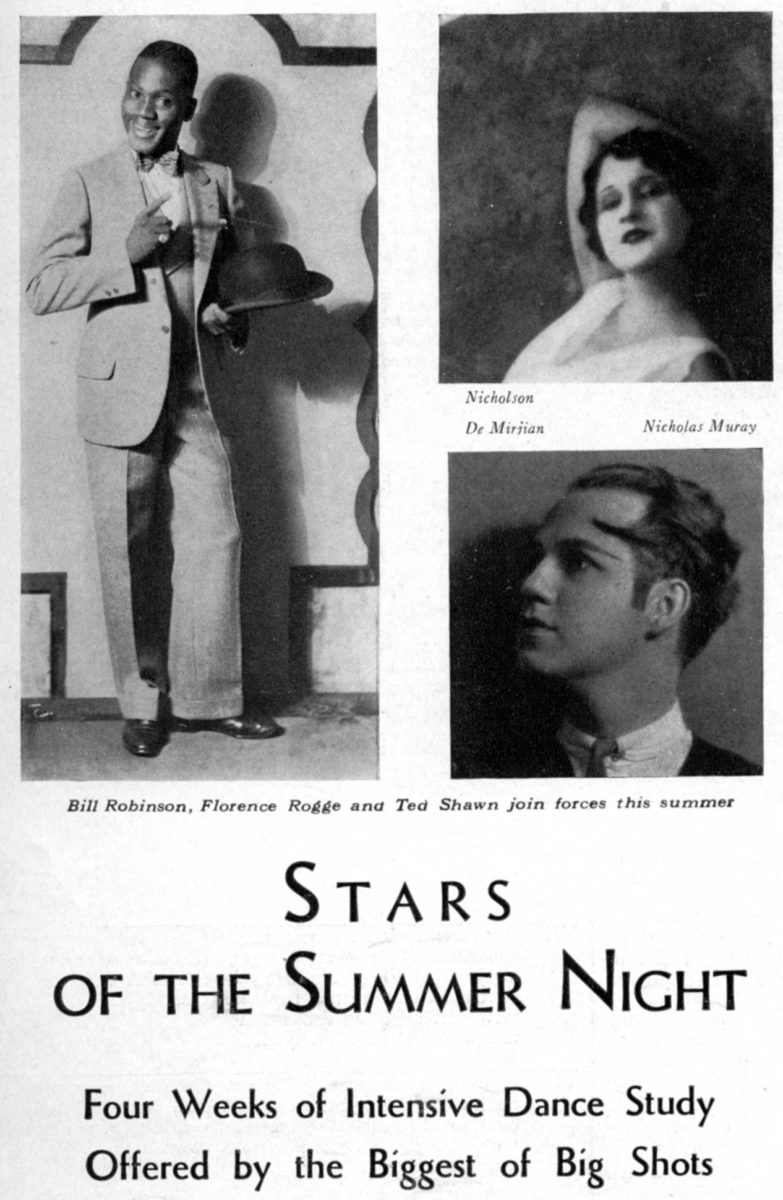

The cultural hierarchy was connected to a racial one. Shawn acknowledged the African-American origins of tap as “a Negro dance” (a simplification of mixed origins). He could admit the virtuosity of Bill Robinson, condescending to it as amusing, and in general, he found tapping by blacks to be “less repulsive,” since he felt that tap “belongs rightfully to them.” But he disparaged tap—as he did the ballroom dances of the thirties whose African-Americans origins he considered “alien to American nature and temperament”—for having arisen not from “plantation Negroes” but from “the sophisticated, hectic Harlem Negro.” This, in Shawn’s mind, made them less “pure.” It seems that advances in black sophistication did not strike Shawn as positive.

In his supercilious opinions of tap, Shawn was far from alone. “Serious dance lovers rate tap pretty low,” wrote the critic Walter Terry in a 1941 column about tap for the New York Herald-Tribune. Terry (who would serve as artistic director of the Pillow in 1973) also recognized tap as “America’s most popular form of theater-dance.” And he expressed the widely held assumptions that tap was limited in technique, range, body movement, associated music, and emotional scope. But since tap was “America’s only indigenous dance form,” Terry hoped that it might be expanded to “become a valid facet of the American dance art. . . no longer limited to the field of pure entertainment.”

In Shawn’s view, though, “places of cheap entertainment” were where tap belonged. He argued in favor of “keeping it out of those places where it decidedly does not belong,” including educational institutions and “the home.” He could keep it out of his home, Jacob’s Pillow, and he did, mostly.

The main exception came near the beginning, when there was a Jacob’s Pillow but not quite yet a Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. In the 1941 International Festival of Dance, organized by the British ballet stars Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin, a tap dancer appeared at Jacob’s Pillow: Paul Draper.

Walter Terry’s column about tap was prompted by this very appearance, because Terry—as was common among critics of the day—considered Draper to be the best hope for raising the standards of tap.

Draper’s family was socially and artistically prominent. He had studied enough ballet at the School of American Ballet to incorporate ballet body placement, positions, and steps into his tapping. He danced to classical music. The Saturday Evening Post rated him the best tap dancer in the world. The Washington Post decreed that “to denominate him a ‘tap dancer’ is a desecration.” Critics recognized what Draper did as “serious art.” If any tap dancer could make it past the prejudices of Shawn and the like-minded, Draper was the one.

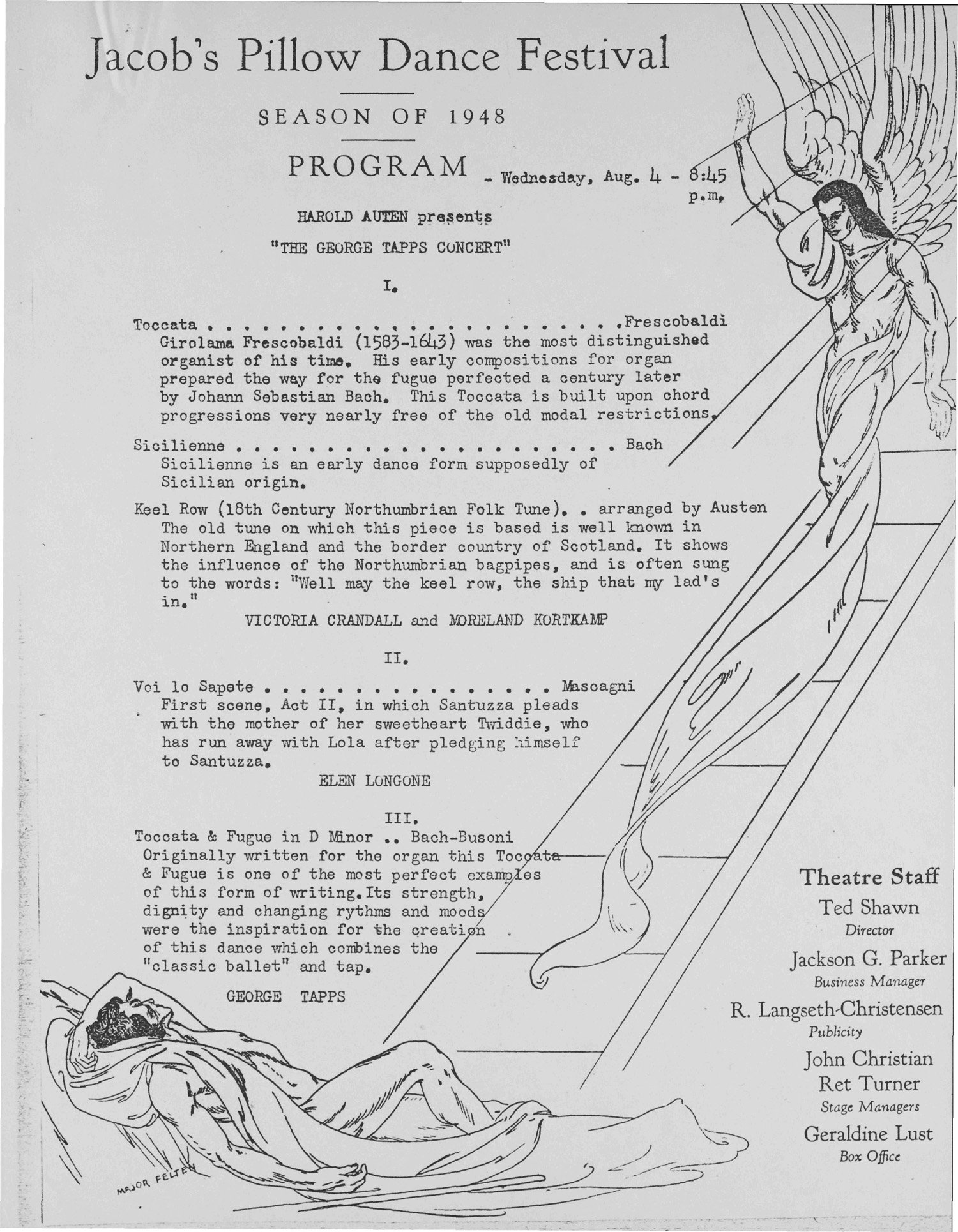

But after the Jacob’s Pillow Festival started up the following year, not even Draper was asked to return. In a kind of fluke, George Tapps did perform on a mixed program in 1948.

Born Mortimer Alphonse Becker, Tapps was a Broadway and cabaret performer who followed Draper’s lead in tapping to classical music and borrowing from ballet. At the Pillow, Tapps tapped to Bach and Schubert and De Falla’s “Ritual Fire Dance,” and he ended with a we-know-better-now parody of low vaudeville hoofers. A few years later, Tapps would blame tap dancers who didn’t study ballet for a slump in tap’s commercial popularity. It was the start of slow, decades-long decline of tap away from the center of American popular culture. No longer an invasive species, it became endangered, and yet was not offered protection in sanctuaries like the Pillow.

Tap Lands on Pillow Rock: “It’s About Time”

After Shawn’s death in 1972, the place of tap at the Pillow didn’t change quickly. In 1976, Norman Walker, who was then artistic director, hired a young woman named Jane Goldberg to teach a three-week course in tap as a form of American ethnic dance. Goldberg herself had been studying tap for only a few years, but she was an uncommonly dedicated student who was also a journalist. She had been seeking out many of the great black tap artists who had found other lines of work when the tap jobs dried up. She was on a mission to bring them back, and their kind of tap, too, and to gain it some of the respect it had never gained before.

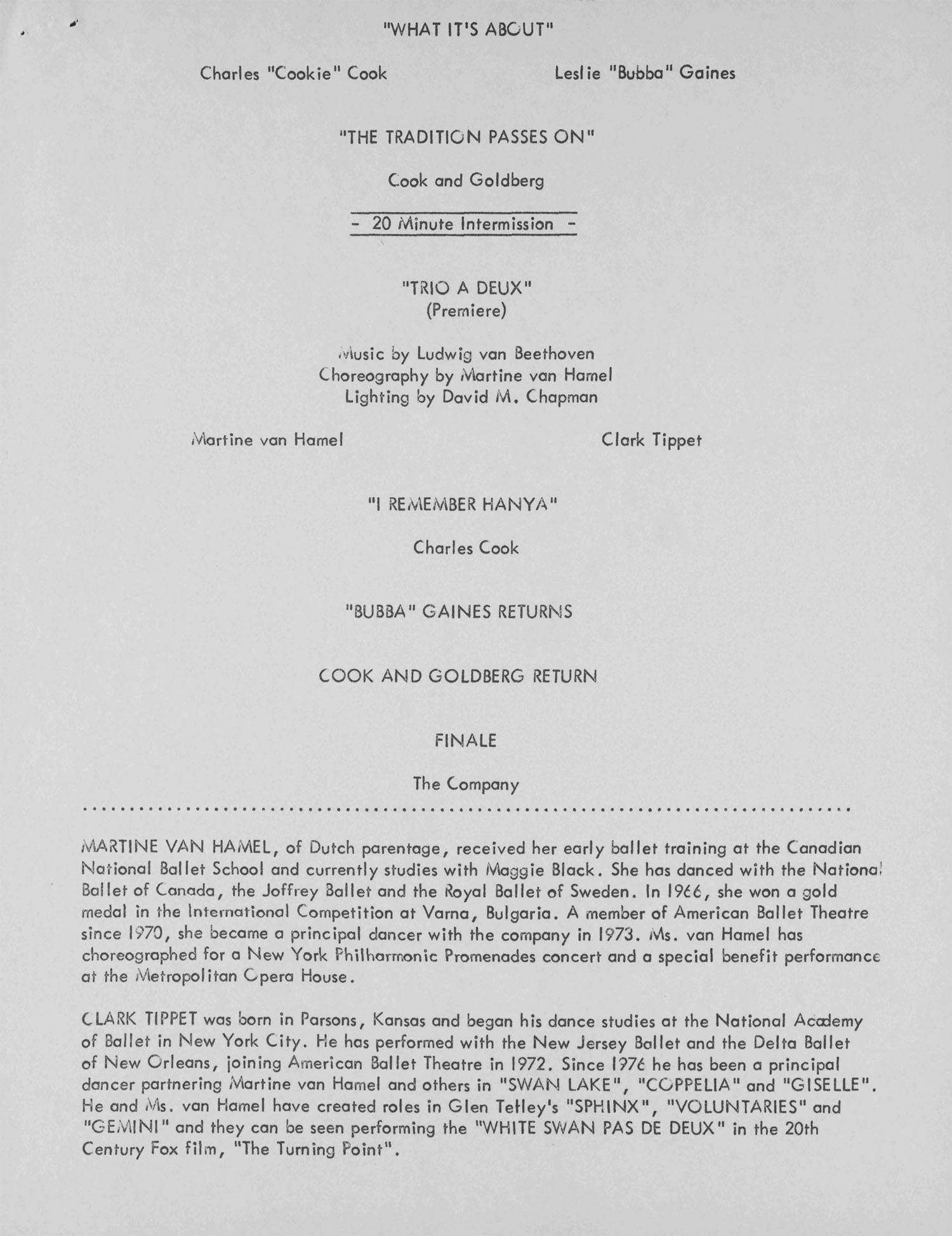

Soon, Goldberg began performing with her teachers. In 1978, she presented her first show, “It’s About Time,” and after it received rave reviews (“Break down the doors if you have to,” Jennifer Dunning wrote in the New York Times), she began to receive other offers. That summer, she appeared at the American Dance Festival, which hadn’t presented tap since a Draper performance in 1963. A month later, after a last-minute cancellation, Goldberg was added to a performance at the Pillow, sharing a program with the ballet stars Martine van Hamel and Clark Tippet.

No footage exists of that particular show, but photos capture some of the fun and cross-generational camaraderie among Goldberg and the charismatic veterans Charles “Cookie” Cook and Leslie “Bubba” Gaines.

The next time Goldberg appeared at the Pillow—only 31 years later for a PillowTalk about her memoir, Shoot Me While I’m Happy—she was filmed, and the footage of her trademark tapping-while-talking (below) captures much of her cheerily delivered dark humor and flighty charm. (It was an act and not an act: no sooner had the talk started than she began wandering around looking for her purse; later, she ceremonially returned a Ruth St. Denis costume she had taken in 1976.) Laugh at her jokes, but don’t underestimate this woman: she was instrumental in saving tap. Bringing tap to the Pillow was an important part of that achievement.

As Norman Walker remembers it, Goldberg’s performance was a hit. But Walker, who left the following year, didn’t have a chance to ask Goldberg back, and he wasn’t aware of anyone else like her. In fact, there was a whole movement brewing, a tap renaissance.

The Boston chapter made it to the Pillow in 1983, on a pre-season program celebrating winners of the Massachusetts Artists Foundation Fellowship in choreography. One surprising winner was Leon Collins, a 61-year-old bebop hoofer from Chicago who had toured with the Jimmy Lunceford Orchestra but had retired to Boston, where he reupholstered cars and didn’t dance for fourteen years. In the mid-70s, he had returned to performing and to teaching.

Collins, who would die in 1985, was an understated, fastidious dancer whose exactitude could serve his droll wit. That was especially true in the signature number he brought to the Pillow (below), an arrangement of “Flight of the Bumblebee” that segued into “Begin the Beguine.” It was Rimsky-Korsakov approached from the perspective of Charlie Parker, no less brilliant for acknowledging what some might find incongruously humorous about an old black man tapping to classical music. What would Ted Shawn have made of it?

Also in 1983, from Los Angeles, came Jazz Tap Ensemble. This was something new: a collaborative of jazz musicians and tap dancers—dancers who were applying their educations in modern dance to the jazz tap they had learned from veterans of Collins’s vintage, such as Eddie Brown and Honi Coles. These young white dancers, mixing improvisation and choreography in fresh and inventive ways, had college degrees in modern dance and choreography, but that imprimatur wasn’t what attracted the notice of the Pillow’s artistic director at the time, Liz Thompson. She was interested in jazz, and had instituted a Sunday jazz series as one of several ways of broadening the Pillow’s range beyond Shawn’s tastes. She recalled remarking at the time that Shawn was probably turning over in his grave.

Thompson, though, was not, in her words, “very interested in tap.” And apart from a repeat performance by the Jazz Tap Ensemble’s Fred Strickler on “Jazz Parade” mixed bill in 1984, Thompson didn’t program any more tap during the remaining seven years of her tenure. The innovative tap choreographer Brenda Bufalino was on the Pillow teaching faculty in 1986, but Bufalino’s pioneering American Tap Dance Orchestra wasn’t invited to perform, nor were any of the other tap companies of the era: Manhattan Tap, Anita Feldman, Gail Conrad. In 1986, the Colorado Dance Festival held a landmark summit, bringing this younger generation together with venerable and revitalized tap masters: Honi Coles, Jimmy Slyde, and others, joined by tap’s middle-aged star, Gregory Hines. It was a tap festival that gave birth to other festivals. Yet none of this ferment was reflected at the Pillow.

When Sam Miller took over as Pillow director in 1990, he had many ideas about continuing tradition and “getting as much variety on the stage as possible in an equally valued way.” Tap was part of that variety, sometimes. In 1991, Miller programmed Steps Ahead, a sleek male trio led by Mark Mendonca, who had danced with Jazz Tap Ensemble. And twice, Miller brought Rhythm in Shoes, a music-and-dance troupe that was experimenting with Appalachian clogging. This, Miller recalled, seemed American to him and befitting the Pillow’s barns. In 1993, he also brought back Jazz Tap Ensemble—which now included the virtuoso Sam Weber and evidence of a greatly talented new generation in Derick Grant and Dormeshia Sumbry. Outside the Pillow, tap had been growing.

Tap in Residence: The Kriegsman Years

Sali Ann Kriegsman, the Pillow’s next director, knew all about it. She had been a co-director (with Marda Kirn) of that 1986 tap summit in Colorado; earlier, she had brought tap to the Smithsonian. She came to the Pillow with a love of tap and a belief that it had been neglected. At the opening night gala for the first season she programmed, Bross Townsend’s jazz band accompanied arguably the best tap dancers in Massachusetts: Dianne Walker and the great Jimmy Slyde.

And then Gregory Hines walked on, a unique master of blending informality with hard-hitting tap, marrying in-the-moment experimentation with the comic deftness of a seasoned entertainer. He seemed completely at ease and happy on the stage, which made the hint of bitterness and hurt in his voice startling when he suggested that the Pillow “could be a place for tap dancers.”

Kriegsman understood that the wooden stage floor of the Ted Shawn Theatre was an uncommonly fine instrument– “the finest floor to dance on in America,” in the words of the Jazz Tap Ensemble director, Lynn Dally. Given a chance to play it with their feet, tap dancers were often moved, mid-show, to share their gratitude with the audience. “We usually get kicked off a floor like this,” said Dianne Walker.

The stage was an ideal surface for Jimmy Slyde to slide across, and that was what Kriegsman allowed him to do (below), opening her first Pillow season with a “Jazz Tap Fest” featuring Jimmy Slyde and Friends. Slyde was nearly seventy, but most of the friends he brought were much younger. They were mentees, acolytes, regular participants in a jam session he ran at the small Manhattan club La Cave, where he gave his upstarts the chance (rare then and still rare now) to improvise regularly with a live band. Among them were many future leaders of tap, including Max Pollak and Herbin Van Cayselle (later known as Tamango).

Another friend was Dianne Walker. An elegant dancer of mature artistry, she had become a beloved teacher, carrying on the tradition of her own teacher, Leon Collins. Kriegsman wanted to take advantage of these pedagogical skills. And so, as a way of opening up a conversation with local residents who she felt were underserved by the Pillow, Kriegsman established a Jazz Tap Residency project, sending Slyde and especially Walker out to perform, teach, and lead workshops throughout the Berkshires. The project had an impact. Visiting the Pillow twenty years later, Kriegsman met a teacher from Pittsfield who told her that the Residency had changed her life.

Kriegsman was open to shaking up the Pillow in other ways, too. From Boston’s Dance Umbrella, she imported Jazz Tap and Hip-Hop. It was a touring project that, by combining tap with hip-hop, illuminated family resemblances and a lineage that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. “Hip-hop might have seemed risky at the time, considering our subscriber base,” Kriegsman recalled. “I remember a bit of trembling myself when the newly appointed president of the Doris Duke Charitable Trust brought her son to the show (I’d just been invited to put in a formal request for $1 million). I needn’t have been concerned; both she and her son loved it. As did our audiences. And we got the $1 million.”

Hip-hop was the expression of black and urban youth, as tap had been—and was, in a smaller way, becoming again. Vincent Bingham, one of the tap dancers in the project, was fresh off Bring in ‘da Noise/Bring in ‘da Funk—the groundbreaking, award-winning Broadway show, starring and choreographed by a young Savion Glover, whose aggressive style some people were calling “hip-hop tap.” In Jazz Tap and Hip-Hop, the hip-hop came courtesy of Rennie Harris, a Philadelphia b-boy with an uncommon gift for translating hip-hop to the concert stage. And among the tappers was Van Cayselle, a Slyde protégé of African descent, born in French Guiana and raised in France, a suave trickster with the quick wits of a longtime busker. Watch the interplay between him and Harris (below); electric in 1997, electric now.

Before handing off the reins to Ella Baff in 1998, Kriegsman summoned Jazz Tap Ensemble one more time, with Slyde and Walker as guests. Among her plans, if she had continued, was a tap residency lab: a program granting tap dancers and tap choreographers space and time to create new work and ready it for performance, opportunities still less available to tap dancers than to practitioners of modern dance and ballet.

A Crescendo of Support: The Baff Years

Giving a curtain speech for Jazz Tap Ensemble during her first season as director of the Pillow, Ella Baff admitted to being “a little in love with tap” and its connection to music and the connections among generations. Years later, she would recall that she “always loved tap” and believed it to be “unjustly marginalized” and “one of the most important cultural forms in American history.” Still, during the first decade of her tenure, the Pillow grew quieter again.

Van Cayselle (now Tamango) came back, in 2001, with Urban Tap, his African-diaspora jam session And at the gala in 2002, none other than Savion Glover brought the noise and funk (below). Tap was more often heard in the free Inside/Out program (notably from two members of the international wing of the Slyde school: Roxane Butterfly, from France, and Max Pollak, who was born in Austria but who was crossing tap with Afro-Cuban culture). But there was no tap on the Pillow’s main stages until Glover returned in 2005.

The most famous tap dancer in the world since the 2003 death of Gregory Hines, Glover brought some younger dancers along and he brought back Slyde and Walker, who by now stood for what “Tap Dance at the Pillow” meant.

Between those veterans representing classic tap and Glover pushing tap to unprecedented heights of virtuosity, traveling far and deep in long flights with a jazz band, it was an exhibition of tap that would have been hard to follow. No tap dancer got a shot for four more years.

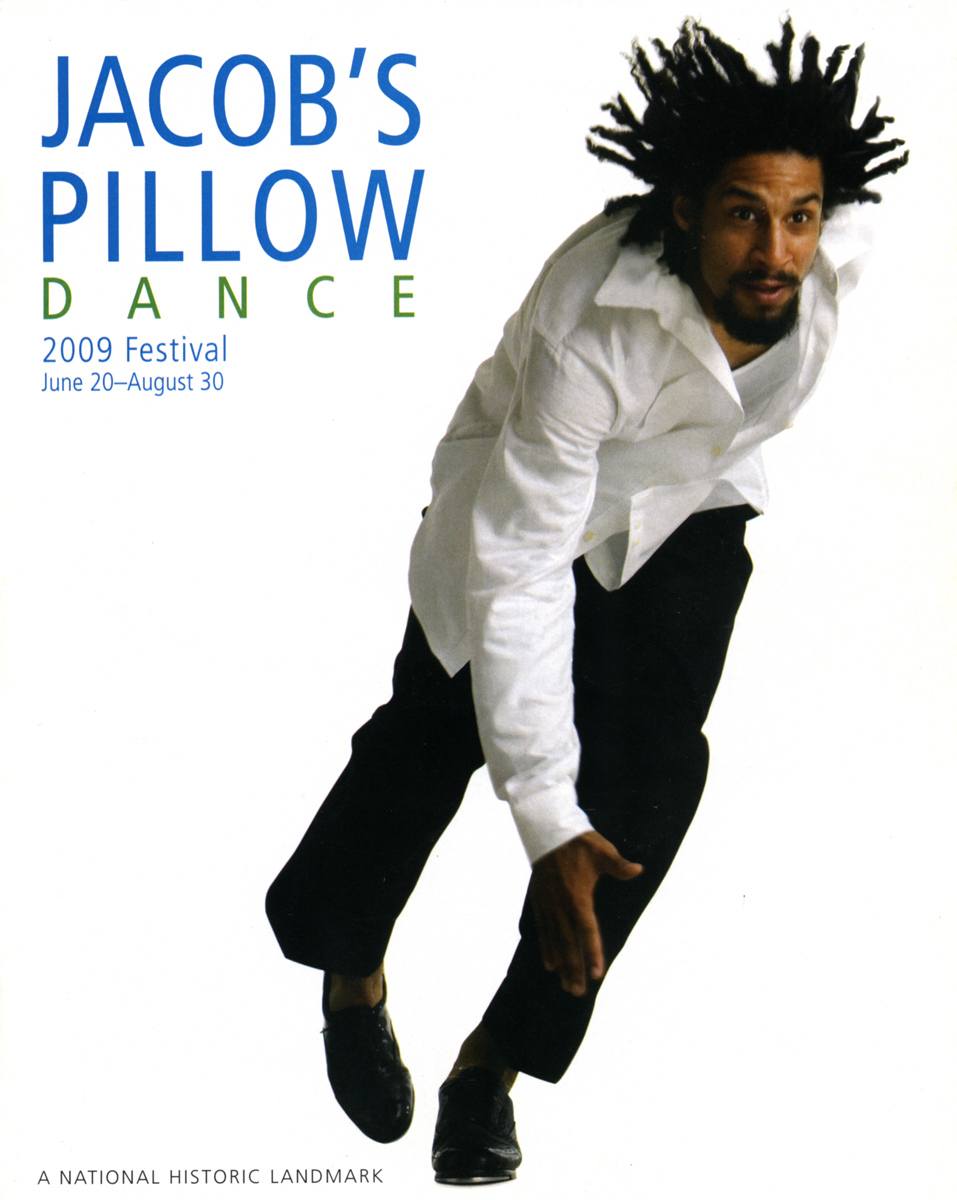

Then, at the end of the 2009 gala, Jason Samuels Smith took the stage.

He took the whole Ted Shawn Theatre, really, spreading his mind-boggling technique up and down the aisles and stairs. “I knew the theater was made of wood,” Smith remembered, “and I wanted to use as much of it as possible.” It was an attention-grabbing entrance and an ear-opening introduction, as intended. Smith was on the cover of the 2009 Pillow brochure.

“That made a big statement,” Baff recalled. “It said, This is important.” So did the two-week run that she granted Smith and his company, Anyone Can Get It.

The 29-year-old Smith and his company of young hotshots represented a new generation of tap dancers: inspired by Glover, strongly rooted in tap tradition, and making technical advances at a high rate, but struggling to find an audience. In 2003, his choreography for the Jerry Lewis Telethon had won an Emmy Award, and in 2007, he had made one appearance on the hit Fox TV show So You Think You Can Dance?. Yet, apart from Glover, tap had largely disappeared from the concert dance circuit; most of the tap companies founded in the 1980s and ‘90s had disbanded.

Smith’s show at the Pillow—mixing tight, complex group choreography with improvisational solos and the informal rhythmic conversations of jam sessions and challenge matches—made a strong case for more attention. In his program note, Smith gave a shout out to “dancers who didn’t get to the Pillow” and registered his hope that he “wouldn’t have to wait years to get invited back.”

That same year, Jane Goldberg returned to the Pillow, to talk about her memoir. In the thirty years since she had infiltrated America’s longest-running international dance festival with the invention of the devil, tap had been a sporadic guest. Its place in the School at Jacob’s Pillow became more regular from 2010 onward (with help, again, from the indefatigable Dianne Walker), but anyone interested in the future of tap at the Pillow had to wait for an Inside/Out performance in 2011: another group of talented young tap dancers looking for a break. This time, they got one.

The company was Dorrance Dance, led by Michelle Dorrance. Having grown up in North Carolina, she brought some bluegrass into a Pillow barn but also a tribute in socks to Jimmy Slyde. She had also grown up in tap festivals, and had danced in one of Savion Glover’s companies. Out of that experience, she had forged a compelling style of her own, fleet-footed and gangly, dorky and vulnerable and charming. Even more unusually, she had developed a sense of choreographic shape and a knack for exposing tender emotions in tap technique.

Dorrance was already gaining recognition on the concert dance scene. Her 2011 program at Danspace Project in New York won her a “Bessie” award, the dance world’s closest equivalent to Tonys or Oscars. In 2012, the Princess Grace Foundation gave her its first ever award for tap choreography, and Danspace Project commissioned from her its first evening-length work of tap choreography. At the Pillow, Ella Baff followed suit, granting Dorrance a creative residency, and then, in 2013, the Jacob’s Pillow Award.

Because of the residency and the $25,000 of award money, Dorrance was able to collaborate with one of her idols, the musician Toshi Reagon, and her BigLovely band. Dorrance also pulled in co-choreographers: Derick Grant and Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, who had grown into tap-world leaders since their previous appearance at the Pillow, with Jazz Tap Ensemble two decades prior.

The resulting show, The Blues Project, was an advance in Dorrance’s inclusive aesthetic, with subtle nods to tap’s mixed racial history embodied by a mixed-race cast of friends and their shared love for tap. Audiences shared the love, too. Baff provided Dorrance with another creative residency for her next project, ETM: The Initial Approach, an innovative crossing of tap and technology. The work debuted in a two-week engagement at the Pillow. “It was a conscious strategy to build support,” Baff remembered, “not just for Michelle, but for the art form. I had belief.” Such support came to seem prescient when Dorrance won a MacArthur “Genius” Award in 2015.

And the support continued, as Blues Project and ETM made repeat appearances at the Pillow, each of them improved as Dorrance proceeded to tour the shows and tinker. A conversation between Baff and Sumbry-Edwards during one of these appearances led to a Pillow project that brought together the all-star trio of Sumbry-Edwards, Grant, and—returning to the Pillow seven years after he expressed his hope to be invited again—Jason Samuels Smith. Fueled by these dancers’ profound knowledge of tap tradition, their unsurpassed virtuosity, their musicality, and their continual innovation, And Still You Must Swing was a return to first principles. Its title borrowed a Jimmy Slyde remark about insufficiency of mere technique; a jazz trio aided in the musical, spiritual goal of swinging. The guest artist, Camille A. Brown (winner of that year’s Jacob Pillow Award), swirled in other, related dances, born in and of slavery.

The timing of the show gave it extra meaning, in two ways. First: the week of performances coincided with news of the killing of black men by police officers in Louisiana and Minnesota, One night, the show became about that, addressed by the dancers in unplanned verbal outbursts and tears but also through their primary mode of expression: improvisational tap. It wasn’t all bleak. These African-American artists—the three tap dancers were old friends—challenged, surprised, astonished one another. They made one another laugh. They accessed all the joy that is usually associated with tap dance, without hiding the pain that is often forgotten. The dancing that night seemed their way not just of expressing the moment but of surviving it: a visceral, indisputable demonstration of tap’s significance, throughout American history and into the present.

Second: And Still You Must Swing made its debut the same year that Dorrance’s ETM returned. This made the 2016 season, Ella Baff’s final one, the first ever to feature two different tap shows on the Pillow’s main stages, an important step in the American art of tap becoming more than a novelty, closer to joining ballet and modern dance as normal parts of the programming at America’s foremost dance festival. “I hope I’ve left tap in a better place,” Baff said. Even considering the shaky, inconsistent history of tap at the Pillow, lovers of tap had some reason to believe.

PUBLISHED December 2017