Introduction to Bharatanatyam

Bharatanatyam has been the most popular Indian classical dance style performed at Jacob’s Pillow since the 1940s. The first part of this article is a brief overview of historical and aesthetic facets of the form. The second part chronicles the Pillow’s connections to two of Bharatanatyam’s hereditary dance artists, marking the beginning of an exceptional dance tradition which was propagated in the U.S. since 1962.

Bharatanatyam is the name of a courtly form of dance from South India that, until the 1930s, was the exclusive preserve of a professional community of artists including female courtesans (devadasis) and their male musicians and dance-masters (nattuvanars). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these artists performed dance and music at a range of sites: royal courts, salons of the landowning elites, at marriages, and occasionally in temples, particularly at the time of calendrical festivals. Each of these contexts had its own set of dance and music compositions, though there was also a natural overlap, and technique and texts could sometimes be transferred from one context to another.

The most virtuosic dances were performed in courtly and salon settings, and not in temples. The court or salon repertoire was variously known as chaduru or sadir (“performed before an audience”), melam (“troupe” or “band”), mejuvani (“entertainment for a host”), kaccheri (“concert”) and kelika (“play”) in the Southern Indian states of Tamilnadu and Andhra Pradesh during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This court repertoire forms the basis of the modern art form known as Bharatanatyam. This suite of dances, consisting of seven to eight major compositional genres, was crystallized by four brothers, known as the Thanjavur Quartet in the nineteenth century, in the Maratha-period court of the city of Thanjavur. It displays a logical and gradual unfolding of the form, and provides a balanced representation of the two elements of nritta (abstract dance) and abhinaya (mimetic dance). The majority of dance compositions in the traditional repertoire were meant to be embodied interpretations on poetic texts that were usually erotic in nature. Longing, separation, and union were the core situations that characterized the poetic texts that were performed in courtly and salon contexts.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, a series of social reforms were ushered in by reform-minded Indians that dislodged devadasis from their traditional socio-cultural and religious roles. This included passing legislation that criminalized devadasi lifestyles, over a drawn-out nearly hundred-year-long public debate. Devadasis, who had non-conjugal sexual relationships with men as their mistresses or second wives, In the twentieth century, T. Balasaraswati emerged as one of the few women from the devadasi community who managed to carve a livelihood for herself despite the challenges of such social stigma and marginalization.did not fit into the new paradigms of womanhood that were being enforced by the Victorian ethics of colonialism and a nationalist resurgence of indigenous patriarchy that valued women’s domestic roles. Today, the art of the devadasi community has emerged on urban stages in India through a complex process that re-populated and re-structured it, and many women of the devadasi community have been severely marginalized and socially and economically disenfranchised. In the twentieth century, T. Balasaraswati (1918-1984), emerged as one of the few women from this community who managed to carve a livelihood for herself despite the challenges of such social stigma and marginalization.

The technical aspects of Bharatanatyam can be divided into two major elements: (1) nritta, or abstract, non-representational movement; and (2) abhinaya, or textual interpretation, representational movement.

(1) Abstract movement, non-representation dance includes a technique grounded in mathematically-oriented rhythmic structures. The technique follows principles of symmetry and geometry. Musically it is rooted in abstract vocalized rhythms called solkattus (“bundles of sounds”). The basic unit of movement in Bharatanatyam nritta is called adavu from the Tamil √adu (“to dance”). The movements usually involve all of the major limbs of the body, and are accented by decorative hand gestures which do not carry any meaning. A typical adavu is divided into several “steps,” each indicated by a different vocalized rhythm (solkattu).

(2) Representational, narrative dance is grounded in stylized mimetic technique. The Sanskrit word, Abhinaya is from the √ni (“to carry”) plus the prefix abhi (“toward”), thus signifying the act of communication. It is musically rooted in songs that essentially contain erotic poetic content. Abhinaya in Bharatanatyam consists of a kind of stylized vocabulary of gestures. The basic sites connected with these gestures are the face and the hands. Hand gestures (also called hastas or mudras) are of two kinds: single-hand gestures and combined-hand gestures. The meaning of the gestures is almost entirely derived from context. The same gesture—the one called hamsasya, for example—can refer to concepts and objects as unrelated as a swan, dew-drop, truth, time, nose-ring, and bee. The thematic content of most of the traditional repertoire of Bharatanatyam focused on love and eroticism. Consider the song-text of this popular Padam (“Payyada”), an erotic genre of musical poetry, composed by the poet Kshetrayya in the seventeenth century:

The Lord who always slept with head on my breasts…

Ayyayyo! now he’s sick of me.

His eyes fixed, unblinking on my face,

He would say, “When dusk falls, your face, alas, will be hidden in the dark,”

and then ask me, in broad daylight for a lamp

Ayyayyo! now he’s sick of me.

Performances of abhinaya involve not only a literal, word-for-word representation of the text or poem, but also the creation of an improvised “commentary” on the text. This “commentarial” elaboration is sometimes called sanchari-bhava (“feelings produced while wandering, roaming about”). The dancer may take up a line from the poem and elaborate upon it, while the musicians sing the line over and over again. Each repetition references a new thought or situation related to the line of text that is being elaborated upon. Traditionally these presentations of sanchari-bhava may be very complex, and the quality of the sanchari-bhava was an index of the performer’s virtuosity. Expert dancers can interpret a single line of text for as long as half an hour or even more.

The Legacy of T. Balasaraswati at the Pillow

There is a long-standing tradition of presenting non-Western dance at Jacob’s Pillow, where Indian dance forms have been de-mystified for American audiences since the 1940s. Several celebrated Indian dance artists have performed consistently at the Pillow. This is a testimony to the discerning taste of Ted Shawn who personally sought out these dancers and invited them to the Pillow. A great aficionado of Indian dance, Shawn himself championed some of the greatest Indian dancers of the twentieth century.

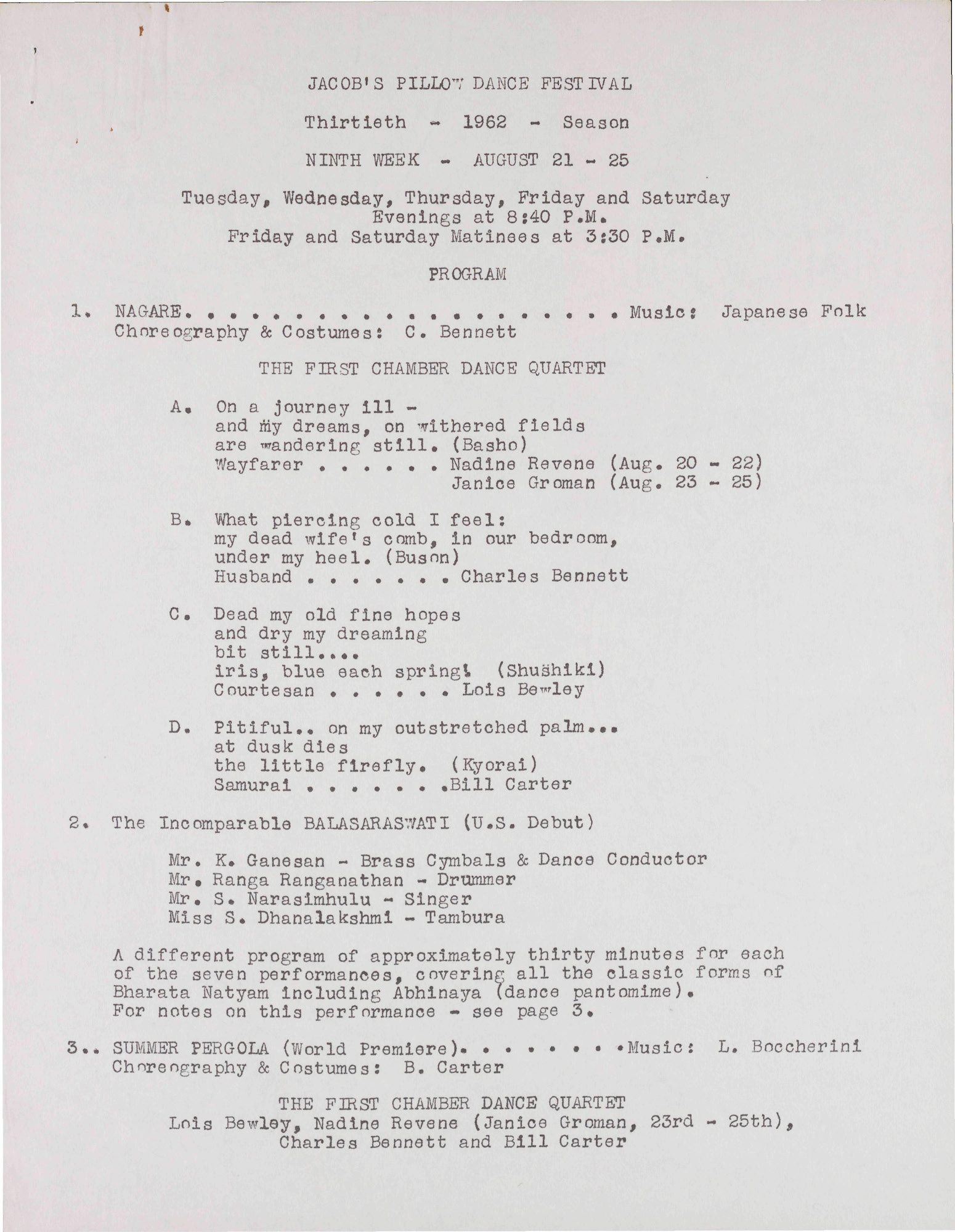

The artists presented at the Pillow most notably included T. Balasaraswati in her 1962 U.S. debut.

T. Balasaraswati (familiarly known as Bala) was from a traditional hereditary devadasi family whose roots as court dancers go back to the 18th century at the royal court of Thanjavur, South India. Her earliest ancestor Pappammal was a court dancer and since then most of her family members have been either singers or musicians. This includes Bala’s grandmother, Veena Dhanammal (1867–1938), an iconic veena player of the 20th century and cousins T. Brinda (1912-1996) and T. Mukta (1914–2007), who were respected singers. Bala’s immediate family also boasted of several eminent musicians including her mother, T. Jayammal (1890–1967) and her brothers, percussionist T. Ranganathan (1925-87) and flautist T. Viswanathan (1927-2002).

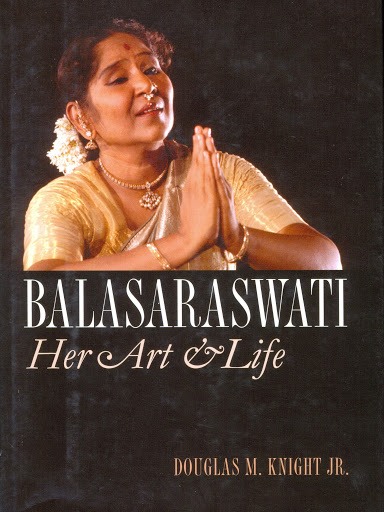

Through arduous training in music and dance, including her own family’s musical legacy, Bala’s inspiring artistry was an original blend of a heightened musicality, a fertile, creative imagination, and solid training in the grammar of courtly Bharatanatyam. Her hallmark was improvisation in abhinaya and the ability to create layers of metaphor through gesture and music. In an environment where Bharatanatyam was being institutionalized and most non-hereditary dancers performed pre-set choreography, Bala, like most dancers from the courtesan community, created a spontaneous expression of improvised abhinaya and music.

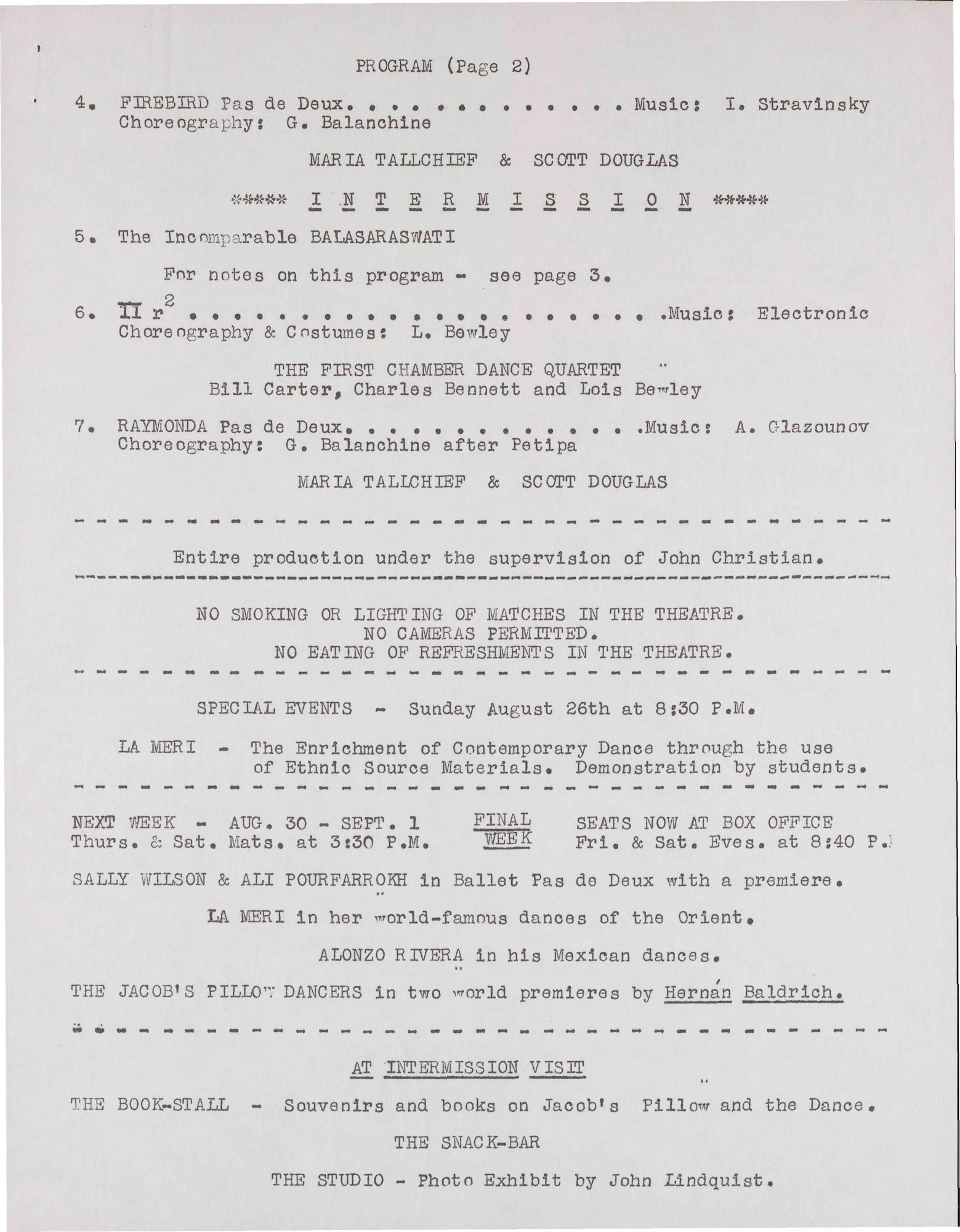

For more on Bala’s brilliance and her unique place in dance history, visit the Jacob’s Pillow campus to watch a 2010 PillowTalk with her son-in-law Douglas Knight where he discusses her work through a commentary on his book, Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life (2010). Or watch online a 2010 video interview of Douglas Knight discussing his book on Bala, along with his son Aniruddha Knight at the Asia Society.

Bala’s daughter Lakshmi Knight (1943–2001) was an exquisite dancer herself who trained directly from her mother. Lakshmi was also a gifted musician and was married to Douglas Knight, a talented percussionist who was trained by T. Ranganathan. Lakshmi and Douglas’s son, Aniruddha Knight (b. 1980) was trained by his mother. Aniruddha made his debut at the Jacob’s Pillow in 1997 when his mother performed and returned once again as a soloist in 2010 as part of the Pillow’s Inside/Out Series. Here is an obituary in the New York Times by respected critic Anna Kisselgoff on the demise of Lakshmi Knight.

While we do not have video recordings of Bala’s performance at the Pillow, we do have a series of still images recorded by longtime staff photographer John Van Lund. And there are documented performances of Bala’s daughter Lakshmi on both the mainstage as well as on Inside/Out. Through Lakshmi’s performances and her post-performance discussion, we are able to understand Bala’s artistic prowess, and also hear an anecdote about Bala’s initial meeting with Ted Shawn on the Pillow premises for the first time. The musicians accompanying Bala’s performance at the Pillow included hereditary dance master K. Ganesan (conductor/nattuvangam), S. Narasimulu (vocals), T. Ranganathan (percussion/mridangam) and Lakshmi on the tanpura (drone).

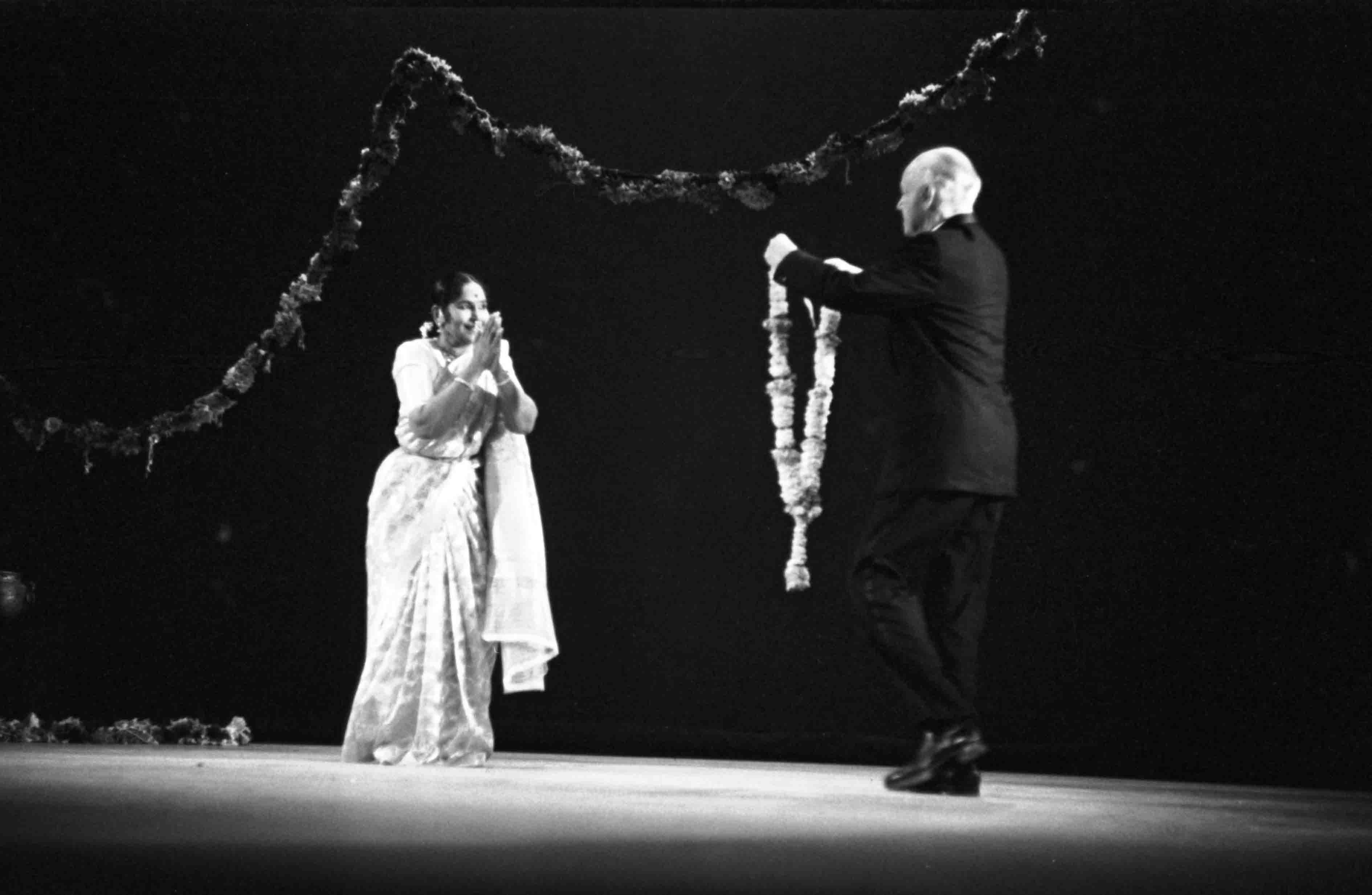

In typical South Indian fashion of traditionally honoring the artist, Ted Shawn honored Bala with a flower garland after her performance.

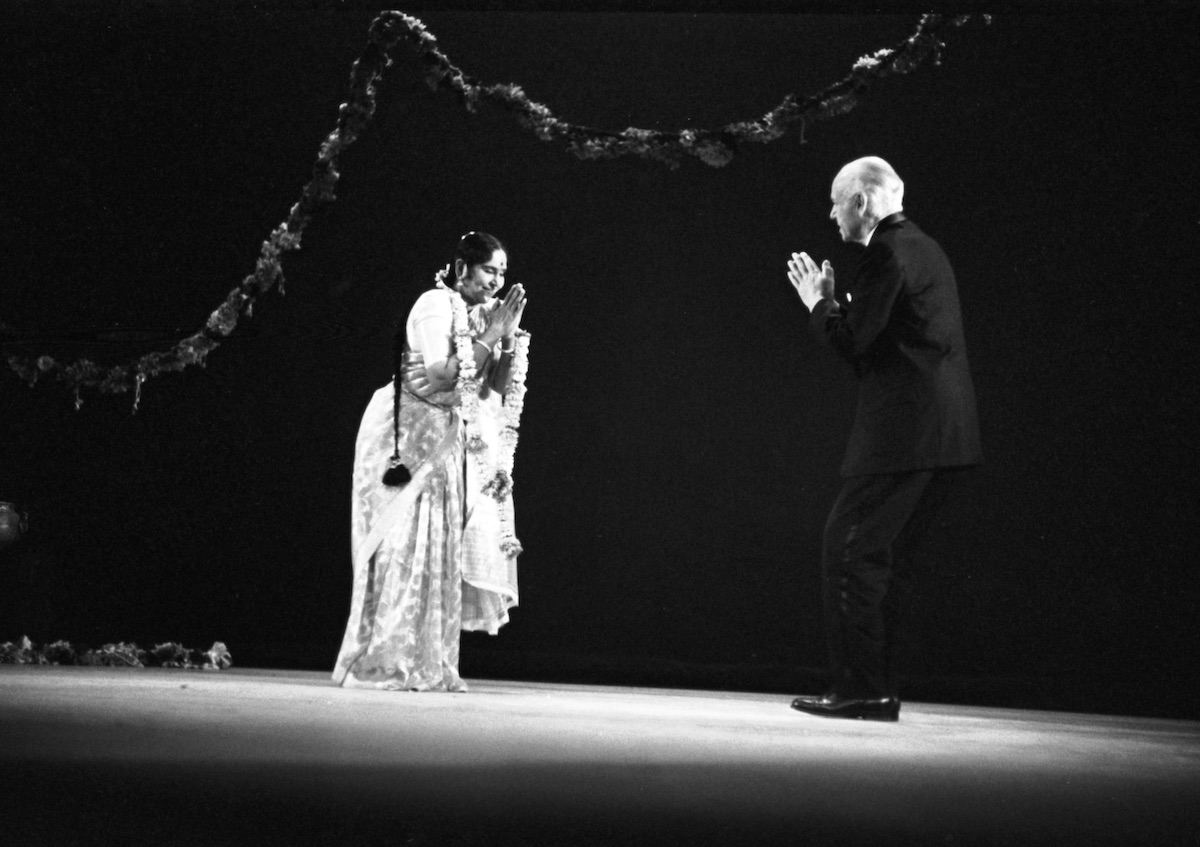

The longtime Pillow fixture, Ruth Alexander, who was also present during the performance, garlanded Lakshmi.

In addition to Ted Shawn and La Meri, Bala interacted with other great dancers such as Nala Najan (1932-2002) during this time.

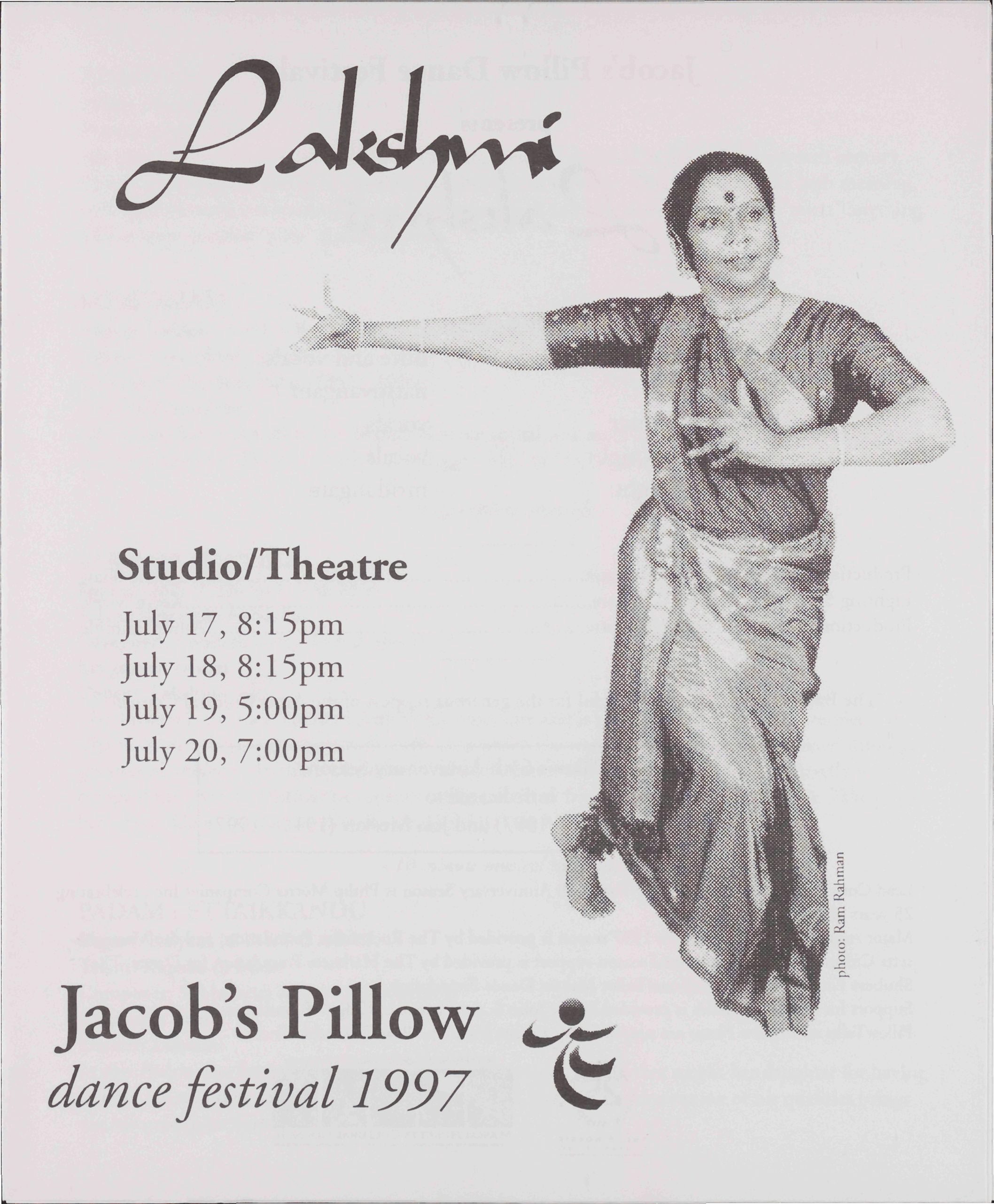

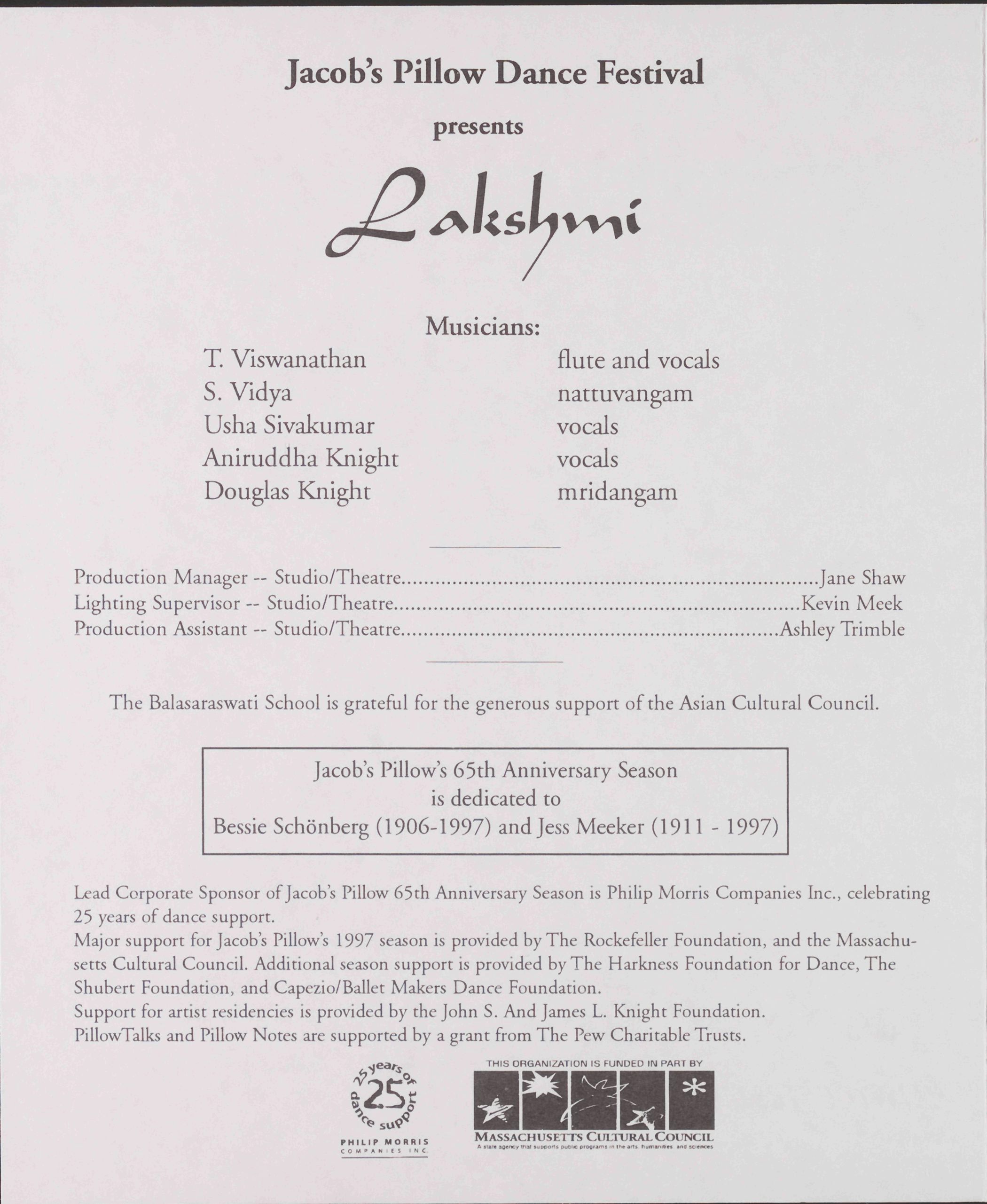

From July 17-20, 1997, Lakshmi Knight was invited to perform by Pillow director Sali Ann Kriegsman in the Festival’s Doris Duke Theatre (then known as the Studio/Theatre) for four nights, when she shared full evenings of Bala’s rich repertoire, accompanied by T. Viswanthan, Douglas Knight, vocalist Usha Shivakumar and dance conductor Vidya Narayan. Her son, Aniruddha Knight, performed the first two pieces (Alarippu and Jatisvaram) as a warm-up before Lakshmi performed for the rest of the evening. Her repertoire at the Pillow included some of the gems of her mother’s repertoire including staple courtesan dance genres such as the Varnam and the Padam.

Below are two examples of abstract dance and abhinaya as they came to life on the modern stage through Bala’s unique style, carried forward by her daughter Lakshmi.

First, here is an example of Lakshmi performing a jati, a cluster of complex rhythmic sequence from the Varnam:

This is a classic example of Bala’s technique culled from the great hereditary dance master (nattuvanar) Kandappa Pillai (1899-1945), whose son K. Ganesan (d.1987) had earlier conducted for Bala at the Pillow in 1962. Although the sequence is short, it is extremely complex. This kind of short but fiery example of rhythmic sequences is also representative of the abstract aspects of the courtesan dance from Thanjavur as it survived into the early part of the twentieth century.

For more on Bala’s teacher Kandappa Pillai read this description written by one of Bala’s students.

Here is Lakshmi performing a line from “Payyada,” the famous 17th century Padam in the Telugu language:

This kind of leisurely, unhurried depiction of a love lyric is very much part of Bala’s aesthetic. Notice Lakshmi singing over the vocalist as she gets very involved in the interpretation of the poetry. She is economical in her selection of how many gestures she chooses to deploy for a single line or idea. Sometimes she chooses to just make a single glance with her eyes, or at other times, she chooses to interpret each word of a line with individual gestures.

In the post-performance discussion moderated by scholar David Gere, Lakshmi shares an anecdote about Bala’s first meeting with Ted Shawn at the Pillow:

Bala’s brother Viswa and Douglas Knight discuss the complexities of ideas of “tradition” and “modernity” in terms of how they relate to Bala and her family’s legacy.

On July 15, Lakshmi and her musicians presented a free Inside/Out demonstration to make their family’s tradition of dance and music accessible to larger audiences. As an example of such engagements with American audiences, Lakshmi performs abhinaya spontaneously to everyday English words, engaging the audiences with humor and wit:

The Pillow continues to function as an important site for a range of such engagements between global dance forms, issues of political and aesthetic representation, and American audiences-at-large. 2018 was T. Balasaraswati’s birth centenary, and the Pillow celebrated this event with a performance of contemporary Bharatanatyam by the Minneapolis-based Ragamala Dance Company, a short excerpt of which can be seen here.

Balasaraswati (Bala) represented a very unique legacy of Bharatanatyam, integrating a rich musical tradition (through the lineage of her iconic grandmother, Veena Dhannammal) with Bala’s own personal creative genius. Bala’s performances at the Pillow are significant in several ways. First, it was the very first time a member from the hereditary courtesan community of South India performed at the august Pillow stage. It also heralded a new chapter in Bala’s propagation of her unique art in the U.S., a relationship she would continue until 1979, just a few years before she died.https://www.nytimes.com/1984/02/10/obituaries/balasaraswati-is-dead-at-64-classical-dancer-from-india.htm Bala would continue to perform and teach extensively in the U.S. to a whole new group of American-born dancers, and much of this was enabled by Ted Shawn’s original vision of inviting Bala to dance at the Pillow in 1962.

Further Readings

Allen, Matthew Harp. 1997. “Rewriting the Script for South Indian Dance.” The Drama Review, 41 (3), 63-100.

Gaston, Anne-Marie. 1996. Bharata Natyam: From Temple to Theatre. Delhi: Manohar.

Gaston, Anne-Marie. 2018. Bharata Natyam Evolves: From Temple to Theatre and Back Again. Delhi: Manohar.

Khokar, Mohan. 1964. Bharata Natyam Vidwan Muthukumara Pillai. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Knight, M. Douglas Jr. 2010. Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Kothari, Sunil (ed.) 1997. Bharata Natyam. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Krishnan, Hari. 2008. “Inscribing Practice: Reconfigurations and Textualizations of Devadasi Repertoire in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century South India.” In Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India, ed. Indira Viswanathan Peterson and Davesh Soneji. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Krishnan, Hari. 2009. “From Gynemimesis to Hyper-Masculinity: The Shifting Orientations of Male Performers of South Indian Court Dance.” In When Men Dance: Choreographing Masculinities Across Borders, ed. Jennifer Fisher and Anthony Shay. New York: Oxford University Press.

Krishnan, Hari. 2019. Celluloid Classicism: Early Tamil Cinema and the Making of Modern Bharatanatyam. Wesleyan University Press.

O’Shea, Janet. 2007. At Home in the World: Bharata Natyam on the Global Stage. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Peterson, Indira Viswanathan and Davesh Soneji (eds.). 2008a. Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Soneji, Davesh (ed.). 2010. Bharatanatyam: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Soneji, Davesh. 2012. Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Srinivasan, Amrit. 1985. “Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance.” Economic and Political Weekly 20 (44): 1869-76.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. Indian Classical Dance. New Delhi: Publications Division, Government of India, 1992.