Introduction

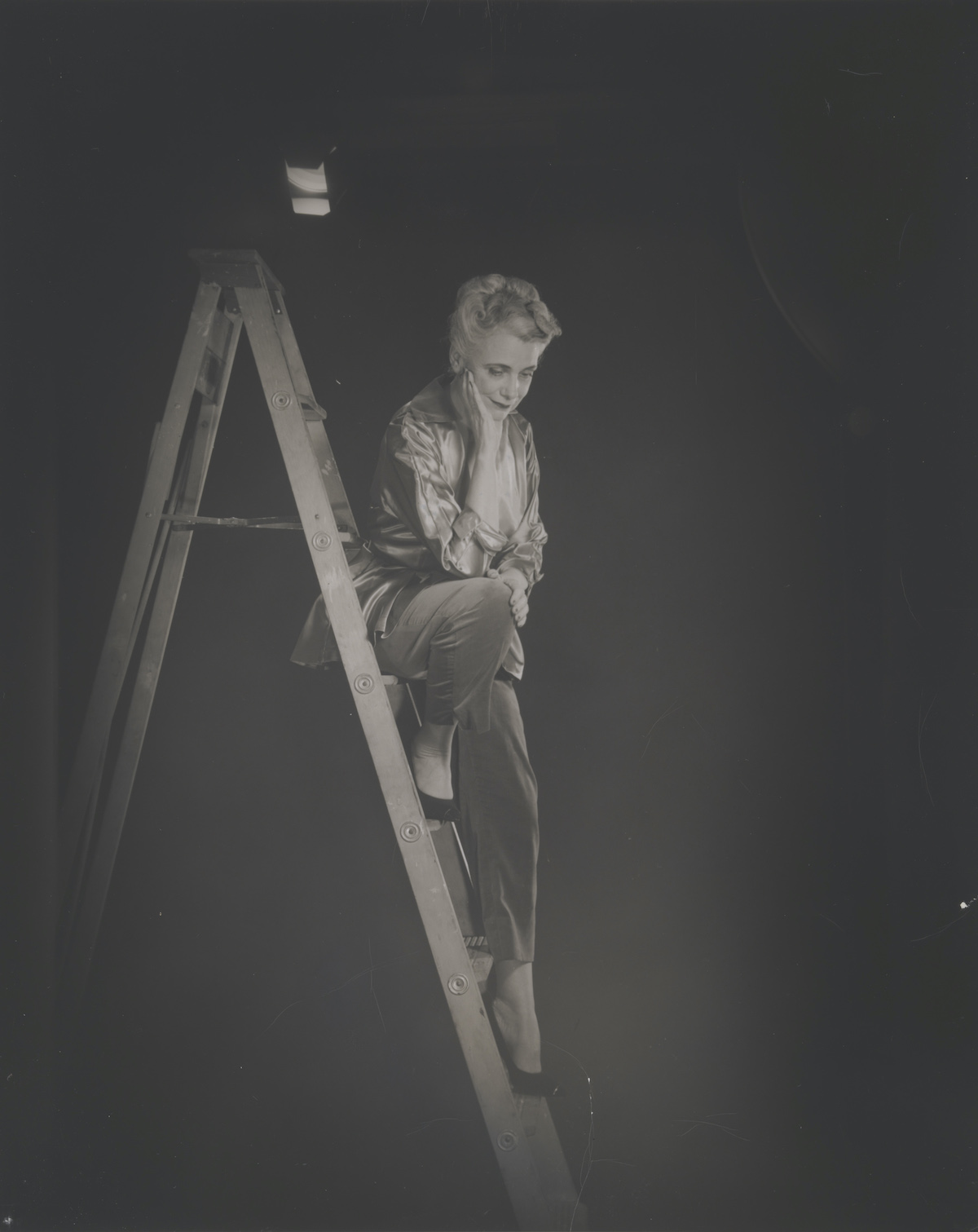

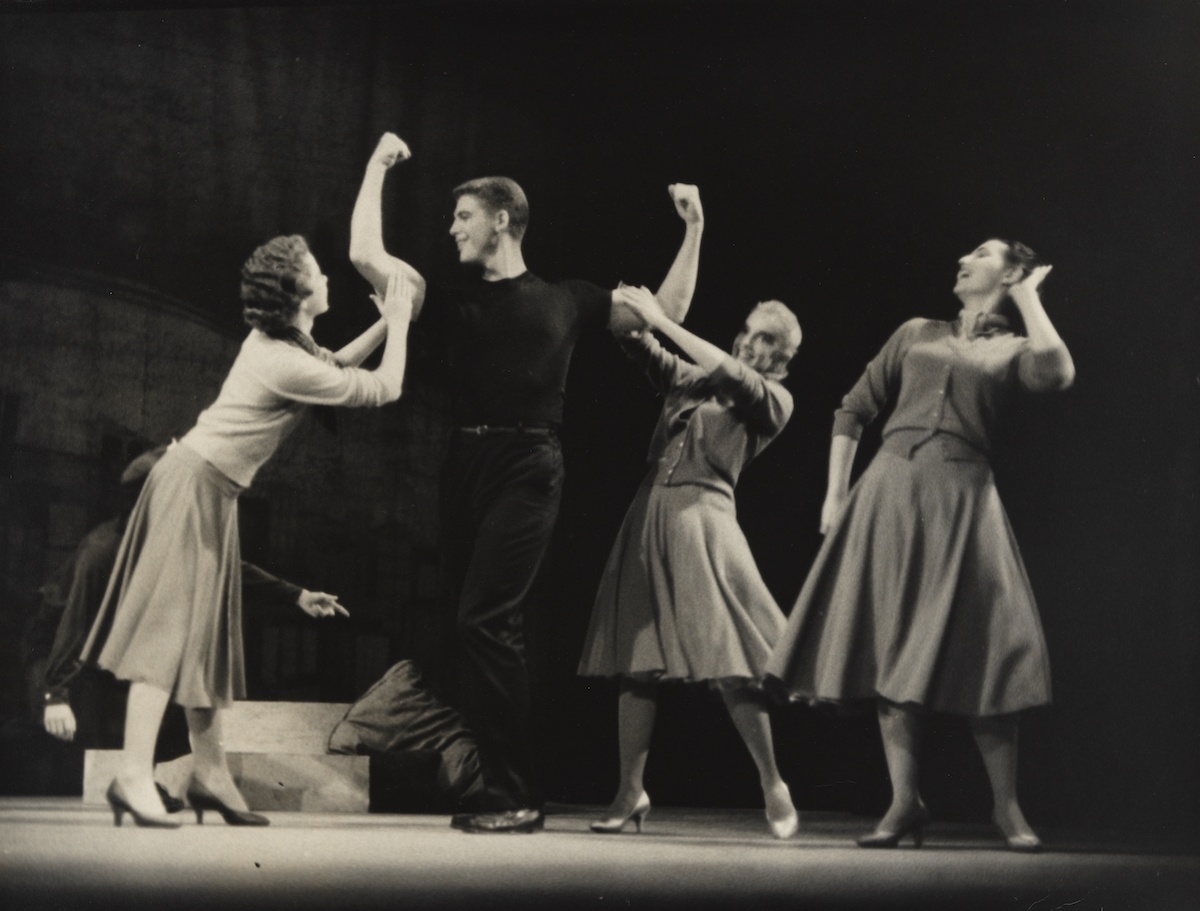

Watching a video of dancers performing Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Biches in 1969 at Jacob’s Pillow, I had to marvel at two things: That the young troupe harked from Buffalo, New York, a city known more for Bethlehem Steel than ballet; and that the director of this young troupe was Kathleen Crofton, a former protegée of Anna Pavlova and a good friend of Nijinska. The lead, Anna-Marie Holmes, had a stellar performing career, directed the Boston Ballet 1997-2001, and headed up the Ballet Program at the School at Jacob’s Pillow for two decades. The Buffalo Center of Dance and its associated company were short-lived, but its dancers went on to impact the ballet world in profound ways.

Such is the story of regional ballet in America: ballet in unlikely places, birthed by a set of circumstances. The glamour of New York City’s ballet history can sometimes overshadow the remarkable spread of this art form throughout the country. Dance/USA estimates there are approximately 34 ballet companies in the U.S. outside of New York City with a budget over $3 million. Surely, there are countless more smaller troupes, pre-professional companies and ballet academies. One would be hard pressed to find a major American city without a professional ballet company, along with several training options.

How did they get there? What confluence of factors gave companies the infrastructure to take root in a city outside of New York? There’s no doubt that Diaghilev’s Paris-based Ballets Russes company (1909-1929), and its next iterations—the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Col. de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe—introduced a generation of Americans to ballet. Anna Pavlova’s American tours also had an impact.

The Russian Influence

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo criss-crossed the U.S. by train from the mid 1930s to 1962, performing one and two-night stands, wowing audiences and slowly developing a ballet-watching habit. We can certainly trace several companies, such as Houston Ballet and Tulsa Ballet, as a direct lineage to the Russians, and those companies are still going strong.

The Russians may have seeded the country with an appetite for ballet, but Americans had to take the next step to claim the art form as their own. The American business ethic is a furious one, as they certainly didn’t wait for the Russians to leave to get going. A Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo program from 1936-37 season features several advertisements from ballet academies. It took some serious entrepreneurial spirit, network building, training opportunities, and strong vision to sustain ballet in this country. We can drop into the history page of any notable American ballet company and see how its origins reveal variations on these factors.

Both World Wars scattered dancers and some ended up in the States, retiring here and starting schools. In my home state of Texas, five Ballet Russe veterans ended up retiring throughout the state. The post-war generation was all about growth and ballet and other arts jumped on that optimism train riding it all the way to the dance boom of the 1970s.

National Association of Regional Ballet

A new unruly art form cannot be sustained without some infrastructure, and that’s where the National Association of Regional Ballet, founded by Dorothy Alexander, comes in. The festivals this organization sponsored throughout the country brought together knowledge, best practices, and talent. Pillow Founder Ted Shawn was a devoted advocate and wrote enthusiastically in his newsletter about hosting and attending such events.

Alexander would go on to create Dorothy Alexander Dance Concert Group, which was renamed Atlanta Civic Ballet in 1946. In 1967, the institution became a full fledged company as the Atlanta Ballet, still growing strong under the direction of Gennadi Nedvirgin. This process of growing into professionalism has been replicated throughout the country.

Boston Ballet

So we had the Russians and a grassroots network. Would that be enough to build infrastructure? Not really. Ballet in America was built in part by visionary individuals who possessed an unwavering dedication to this artform. We see a second pattern of stability when the founder is eventually succeeded by another long-tenured director.

The regional ballet story is an unfolding one and could fill volumes; I chose to start with Buffalo because it’s my birthplace. When I examine the history of the cities where I have lived, we can see all of these elements at work. This quick glance at some of the country’s major companies represents just a small swathe of a much larger movement. For dancers, we look to our local company the way a person might follow the local football team.

In 1973, I moved to Boston, where the Boston Ballet, founded by E. Virginia Williams in 1963, would be my home ballet company. Williams was one of those early ballet pioneers, who unlike most of today’s artistic directors, did not have a performance career. Like Alexander, Williams was dedicated to dance education, and had a trajectory that we see all over the country: first a school, then a civic company, followed by a professional company.

Williams caught the dance bug early watching ballroom sensation Irene Castle when she was only four. Of course, the Russians came through and her parents took her to see those shows, too. In 1959, when Williams took Boston Ballet’s first iteration, New England Civic Ballet, to the First Annual Northeastern Regional Ballet Festival, she encountered Alexandra Danilova, Shawn, and George Balanchine, whose recommendation was crucial for their transformational 1963 Ford Foundation Grant.

Williams retired in 1983 after an extraordinary tenure. She was followed by a string of directors: Violette Verdy, Bruce Marks, and Holmes. Mikko Nissinen has served as director since 2001, and the company once again had the benefit of a director serving over time.

The company returned to the Pillow during the 2019 season with a program that highlighted Nissinen’s achievement with works by William Forsythe, Leonid Yakobson, and resident choreographer Jorma Elo.

Washington Ballet

From Boston, I moved to Washington, DC in 1977, where the Washington Ballet, founded by Mary Day, would become my go-to company. Again, we have a school (founded in 1944) growing into a company. The school was founded by Day and Lisa Gardiner, who danced in Anna Pavlova’s company. More Russian connections were present during the brief time that Ballet Russe veteran Frederic Franklin co-directed the company, which is also the period when the company made its 1960 Pillow debut. Franklin left Washington Ballet to start the National Ballet with a young Ben Stevenson, who would go on to create epic ballet roots in the Lone Star State, first with Houston Ballet, then with Texas Ballet Theater in North Texas.

Day, another strong personality, presided over the helm of the organization for an astonishing 55 years, training such legends as Kevin McKenzie (who would become the longtime Director of American Ballet Theatre) and Amanda McKerrow, as well as nurturing the talent of choreographer Choo-San Goh, the company’s first resident choreographer.

A charismatic young Cuban-American, Septime Webre, took the reins in 1999, taking the company in new directions and increasing its flash and visibility during his 15-year tenure. Former ABT principal Julie Kent took over in 2017 as The Washington Ballet’s story continues to evolve, having the backbone of two long term directors who worked tirelessly to entrench the company into the city’s cultural landscape.

San Francisco Ballet

From Washington, DC, I moved to the Bay area, where San Francisco Ballet (SFB), the oldest troupe in the U.S., would move into the home team spot. It was only a two-year stint for me, but long enough for me to learn of the famous Christensen brothers and their extraordinary efforts to bring ballet to the West Coast. The San Francisco Ballet story demonstrates that Americans were eager to get things going on their own early on in the spread of ballet across the country. It was back in 1937 that Willam Christensen became the director of the San Francisco Opera Ballet’s Oakland branch. By 1947, SFB was its own entity, the same year that his brother Harold was appointed director of the SF Ballet School, a position he held for 33 years.

Willam Christensen would leave SFB to found Ballet West, and the first ballet program at the University of Utah. His brother Lew took over SFB in 1951, a post he held until 1984. Helgi Tomasson took the helm in 1985 and remained until 2022. Three long-tenured leaders are among the many reasons that SFB continues to shine as a beacon of excellence and new work.

Houston Ballet

From San Francisco, I moved to Houston, a city known for oil, rockets, football, floods, and Beyoncé. Yet, ballet has persisted, largely thanks again to the Russians. Houston’s ballet baptism occurred when the legendary Anna Pavlova danced on the Majestic Theater stage in 1916. Later that same year, another troupe dropped in, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, with none other than Vaslav Nijinsky, considered to be the greatest dancer alive at the time. After Diaghilev’s death, Col. de Basil’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo came to Houston every holiday season from the 1930s to the early sixties.

But there came a point when Houston’s ballet fans longed for a hometown ballet team of their own, and here’s where the plot thickens. Most ballet companies are started by one headstrong person; Houston Ballet was started by a group of its citizens, determined to grow a ballet company in their city.

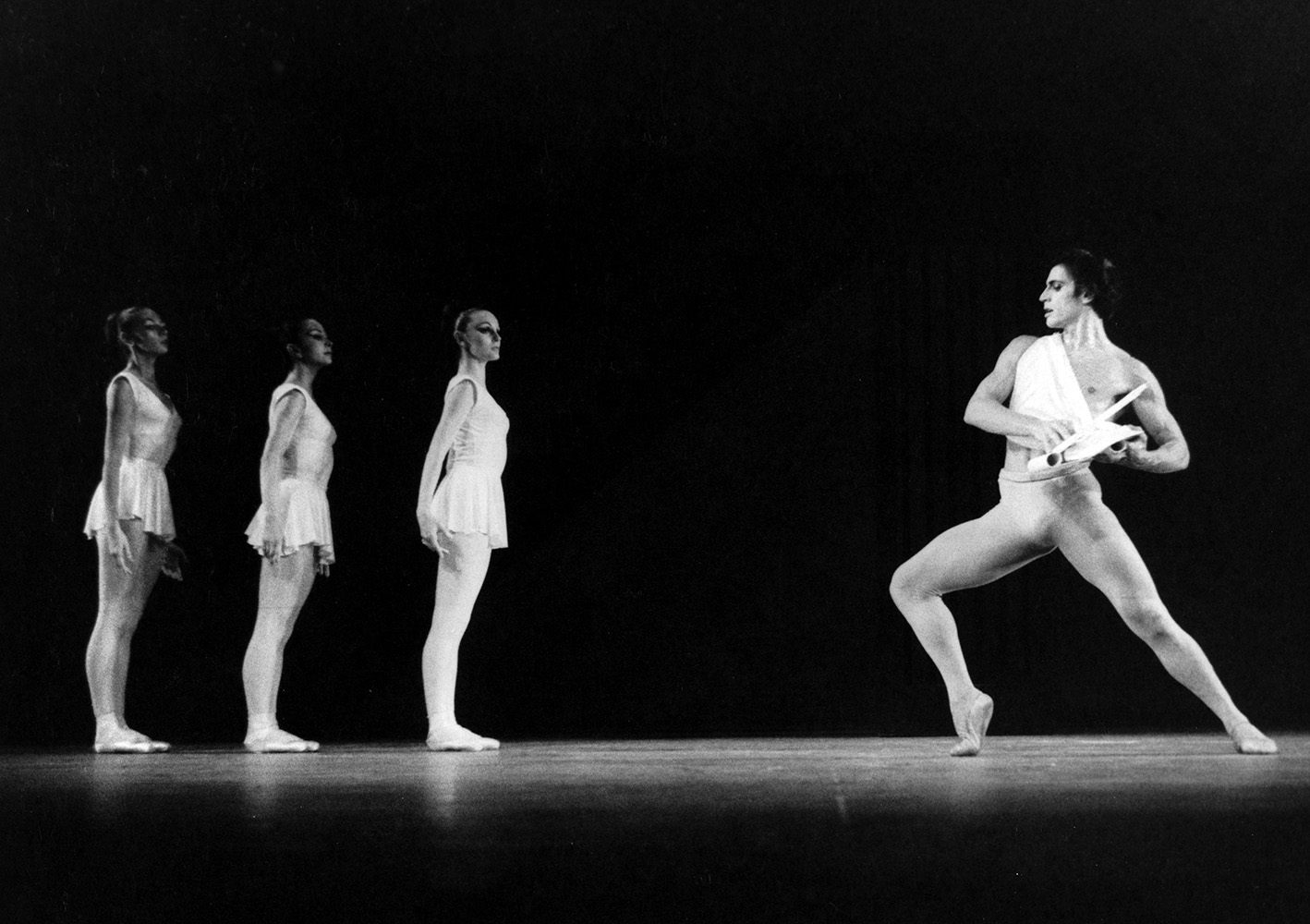

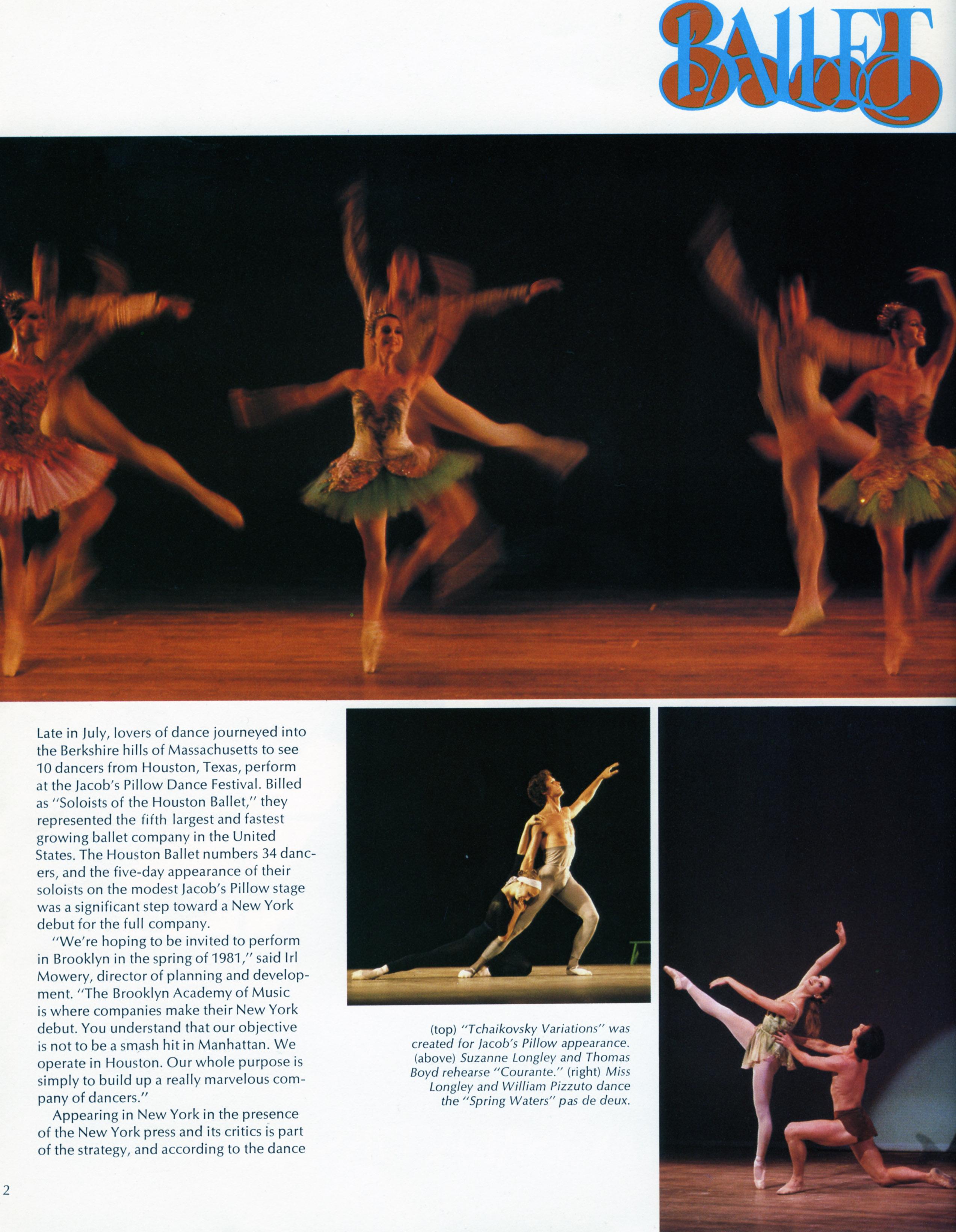

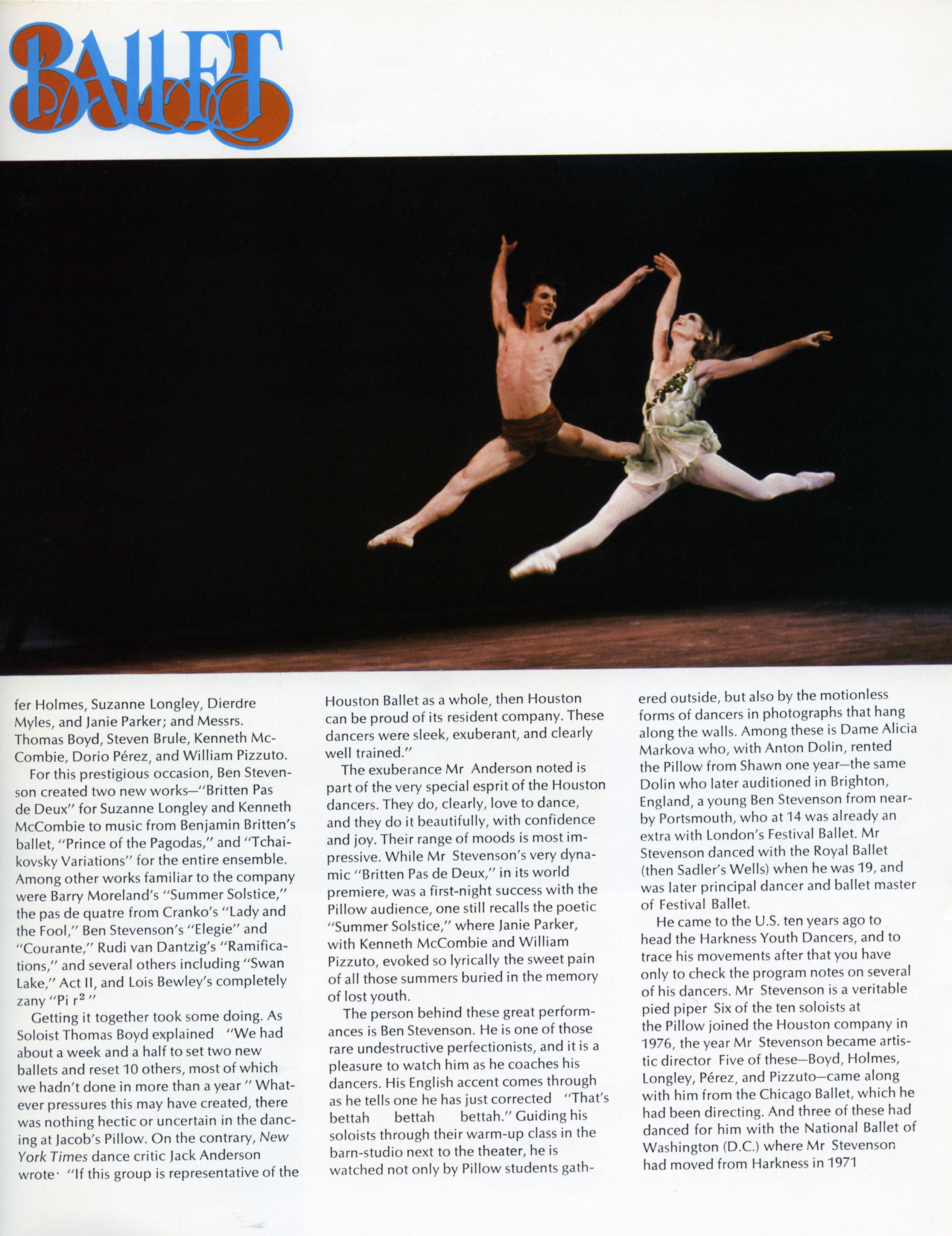

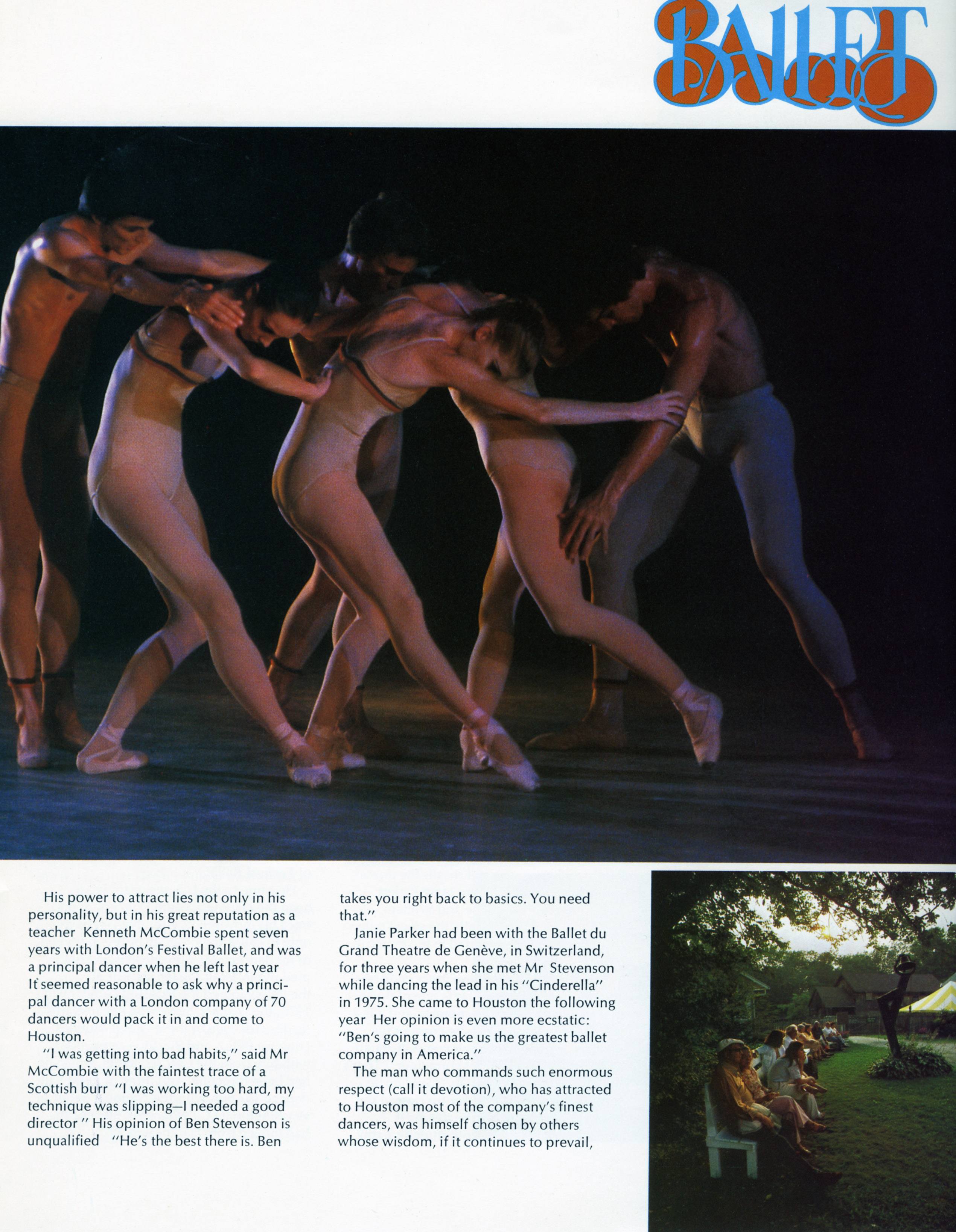

This community of early ballet lovers, which called itself the Houston Ballet Foundation, hired Ballet Russe veteran Tatiana Semenova in 1955. Nina Popova, another Ballet Russe dancer, took over the operation in 1967 as the Foundation moved toward growing a professional company. When it was time to take the next step to grow the operation, the board hired Stevenson, who would transform this fledgling troupe into a world class operation during his remarkable 27-year tenure from 1976-2003. It was during his tenure that the company made its Pillow debut in 1979, with a program of works by Stevenson, Rudi van Dantzig, and John Cranko.

Stanton Welch assumed the leadership in 2003, ushering in a new era, building on Stevenson’s legacy of featuring 19th century classics and strong contemporary work. The Russians may have gotten the company going, but it was Stevenson and Welch who secured the institution’s roots.

Sarasota Ballet

Overlaying my travels gave me a structure to examine ballet’s epic story in America, but it’s only one of many ways to consider regional ballet. Today, it’s a dense, interconnected network of relationships that continue to bring ballet to places outside of New York, and Dance/USA has become an important network-building entity for the field.

Jennifer Homans writes in her epic tome, Apollo’s Angels,“Classical Ballet was everything America was against. It was lavish aristocratic court art, a high—and hierarchical—elite art with no pretense of egalitarianism.” Yet, ballet has in fact taken hold here. Perhaps something else in the American imagination connected with ballet’s largesse. The art form’s expansion also gives us a chance to examine American ideals of entrepreneurship and leadership at work.

Regional ballet allows us to see American exceptionalism at work. Consider the extraordinary achievement of Iain Webb’s Frederick Ashton repertoire at Sarasota Ballet. During the company’s 2015 visit, the campus was filled with Sarasotans beaming with pride over their gem of a local troupe.

Trey McIntyre Project

We also see regionalism within regional ballet! We see choreographers make work deeply tied to place, such as Trey McIntyre’s homage to the Basque people of Idaho, Arrantza, created for Trey McIntyre Project (TMP), then based in Boise, Idaho, Stanton Welch’s Tales of Texas, which highlighted the state’s rich mythology, and Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux’s rousing Shindig for Charlotte Ballet (formerly North Carolina Dance Theatre), which featured clogging in pointe shoes. Ballet has certainly benefited from the fact that we are a nation of distinct identities.

TMP closed its doors as a full-time dance company as McIntyre returned to freelance choreography and other projects, yet he left Boise a changed place. Former company member Lauren Edson, who appears in the above video with Brett Perry, has started a multi-media company known as LED, building on the dance energy fostered during the TMP years. Companies close but they leave seeds of possibility. My hometown of Buffalo never grew into a ballet hub, yet commercial and musical theater dance flourished, and produced the Pulitzer Prize-winning choreographer Michael Bennett. Tracing ballet to other dance forms is a whole other story.

Conclusion

Just like our sports teams, Americans possess a fierce sense of loyalty and civic pride. We own our cultural pillars, which is why I wasn’t remotely surprised to see Houston Mayor Bill White give the curtain speech on the opening night of Stanton Welch’s Swan Lake in 2006. The story of regional ballet in this country is indeed one of belonging.