Introduction

Ann Carlson finds dance in the mundane, and, in the process, reveals the arcane in the familiar. She recognizes choreographic possibilities in the rhythmic tapping of canes, the beauty and grace of fly fishing, the punctuated wave of hailing a cab. Unlike early modern dance choreographers such as Martha Graham, Carlson sees no reason to delve into classic Western myths and literature to elucidate present-day situations. Rather, she looks to the world immediately around her, garnering delight in fathoming the distinct ways in which different people around her move, observing the topics that interest them, and grasping the ways in which they speak.

Real People Series

Carlson is renowned for a group of dances in which she collaborated with local community members, typically non-trained dancers. One series, called Real People, was started in 1986, as Carlson sought information outside of the insularity of the dance studio. In each of these pieces, Carlson turns her attention to groups of people who hold something in common, such as an occupation, a hobby, or a recreational sport. Carlson develops choreography based on movement and words from the “real lives” of her subjects, who are also her collaborators and dancers. These collaborators have included lawyers, fly fishermen, basketball players, cigarette company executives, and security officers.

Carlson immerses herself in the worlds of her subjects. For example, for a section of White (1992) in which Carlson auctions off ballerinas as cattle, Carlson attended cattle auctioneering school in Oklahoma. Also with White, she worked with other kinds of communities, including nuns and visually impaired people. Oftentimes, Carlson plays with the performers’ words, varying their rhythms and injecting repetition, to create scores that are at once music and speech. In See, the visually-impaired performers accompany their dancing with a sing-song chanting based on the phrase “can’t you see me coming?” all the while tapping a rhythmic pattern on the floor with their white canes. This constitutes a soundscape as well as the means for the performers to situate themselves on stage through aural cues.

Carlson’s dances do not put the ordinary onto a pedestal. Rather, through her attention to the detail of their lives and her unmistakable fascination with diversity, she opens a door for us. Through Carlson’s conscientious artistry, we are not voyeurs, but are welcomed inside. For example, in See, the stage lights intermittently go to black, leaving the audience in the dark, unable to see the action of the dance. With this single act of removing the lights, Carlson makes us all visually impaired.

Solo Works

Carlson’s solo works are equally impressive. In her dances, she explores private fears, which she recognizes as shared human experience. Employing choreographic metaphors, she investigates aging, death, sexual identity, and love with incisive clarity, dry wit, and empathy.

Carlson’s Grass/Bird/Rodeo (1998) was a solo dance work, accompanied by live music by Sunrise String Quartet that also included singing and storytelling. One of her starting places was the concept/idea of triptych from art, a painting or carving in three side-by-side panels. In Grass/Bird/Rodeo, Carlson takes on a series of different characters, including a representation of herself as a performer, an androgynous figure in a grass suit, a half-Vegas showgirl/half-bird, and a rodeo announcer. Carlson has a particular and distinct way of moving in each place on the stage, as well as distinct movement vocabularies within each piece. Grass is primarily pedestrian, combining repetitive gestural patterns, with long pauses. Bird interrupts a showgirl learning a new dance routine with flapping wings and bobbing heads. Rodeo brings together trick roping and slow motion rodeo riding with master-of-ceremony type gesticulations.

In between each of the named sections, Carlson acts as a moderator, answering audience questions, as she changes from one elaborate costume to another, preparing for the next solo. As the moderator, she is friendly, approachable and witty. She also gives glimpses of her personal life when she describes the impetus for making the pieces. What she says and how she says it is as choreographed as any movement or gesture in the dance. There are a variety of stories in this piece. Some are complete, some are only suggested, some remain unresolved. As Carlson talks with the audience in between the three sections, she tells some deeply personal stories, revealing details of her private life. Some are quite poignant, like her description of the disjuncture between being at home with her children while the muted TV plays CNN scenes of war-torn Bosnia; other stories are funny. There are some stories that occur in every performance, and others that depend on questions from the audience.

Night Light

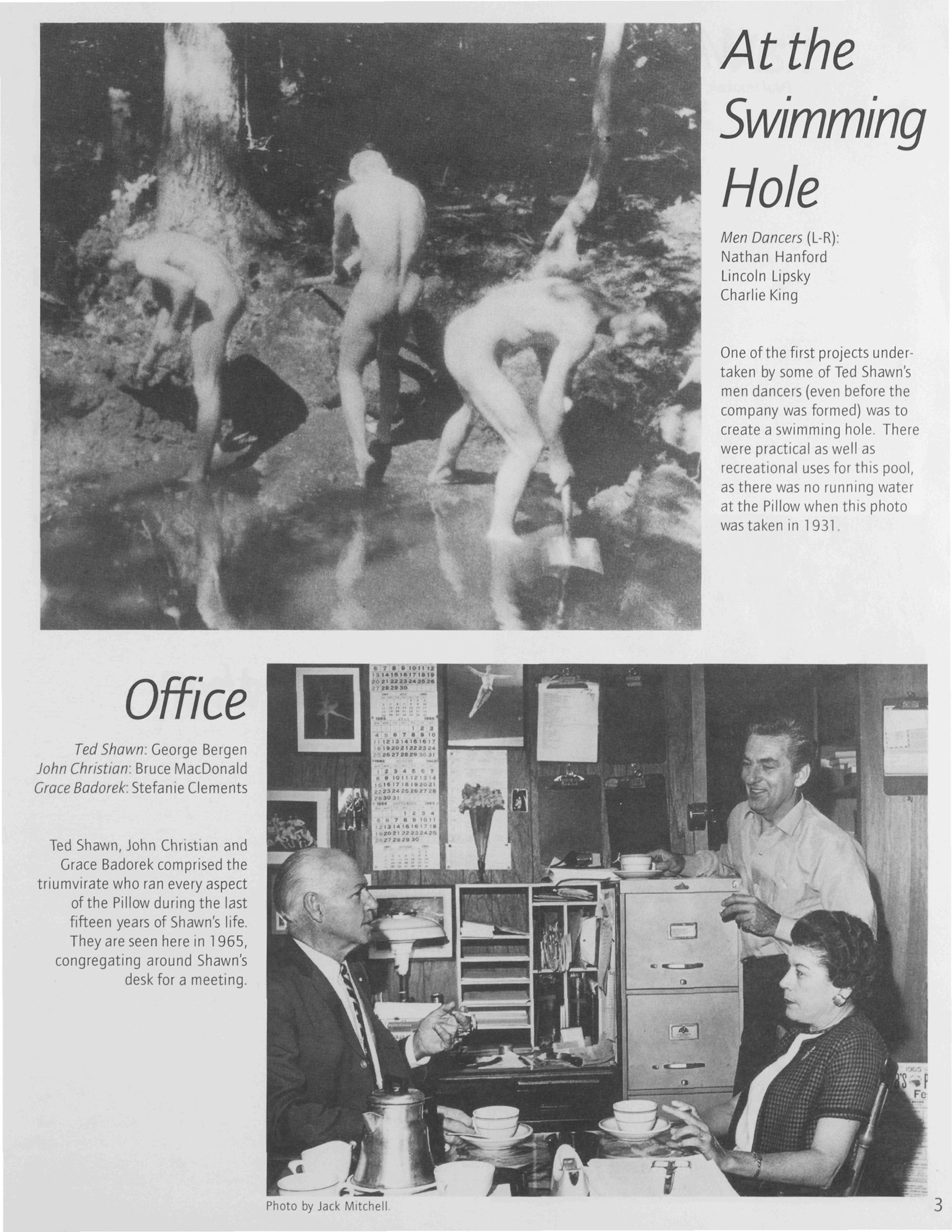

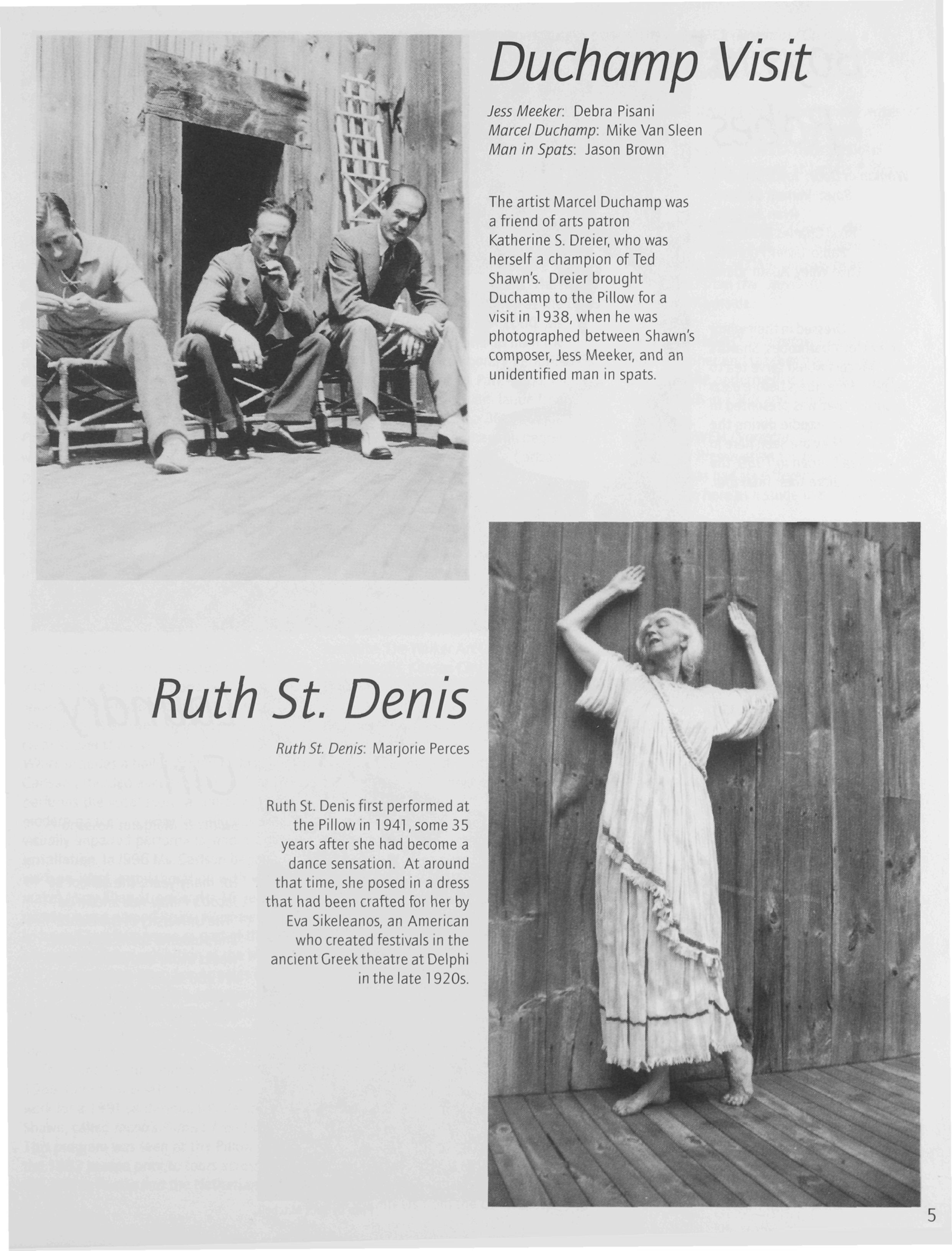

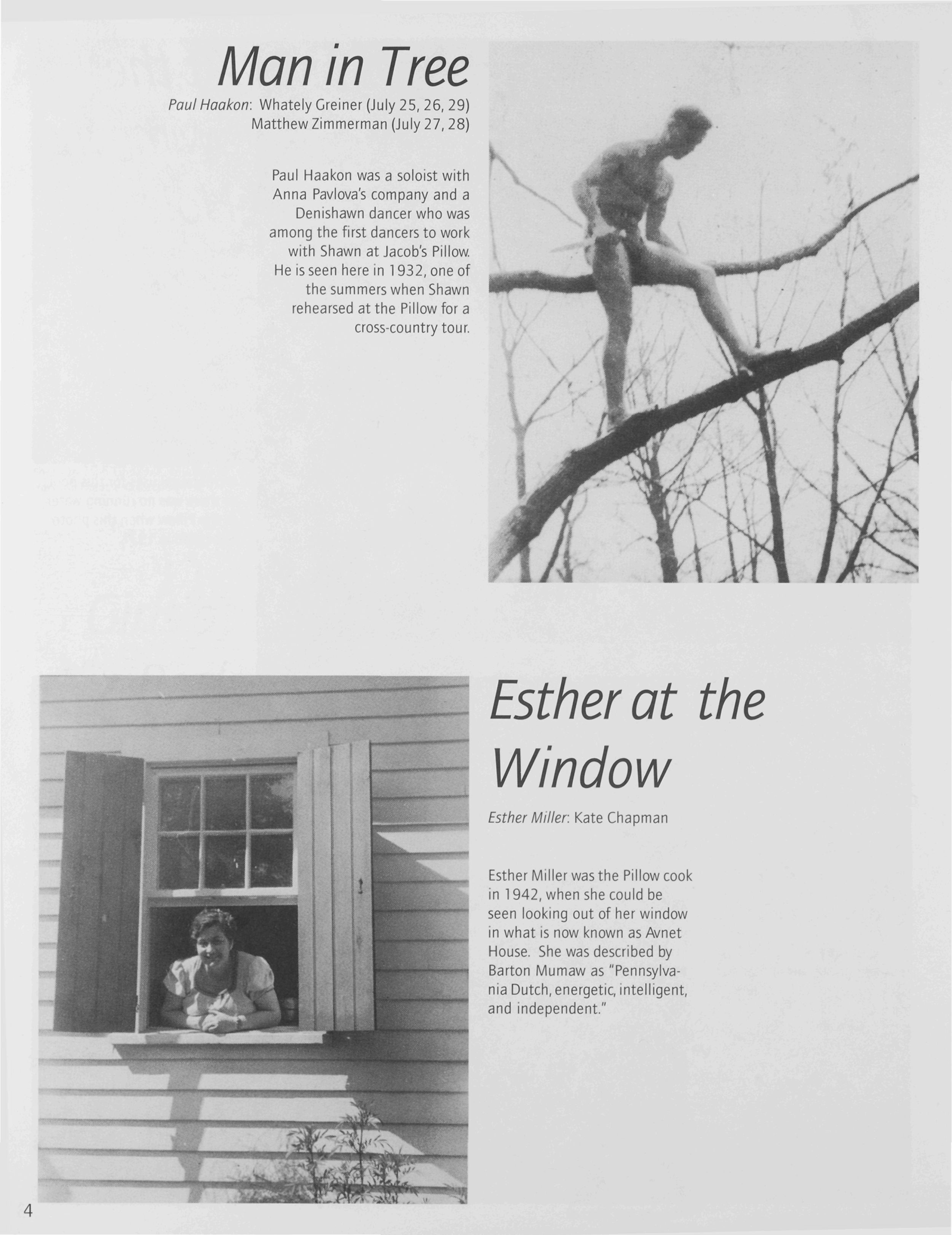

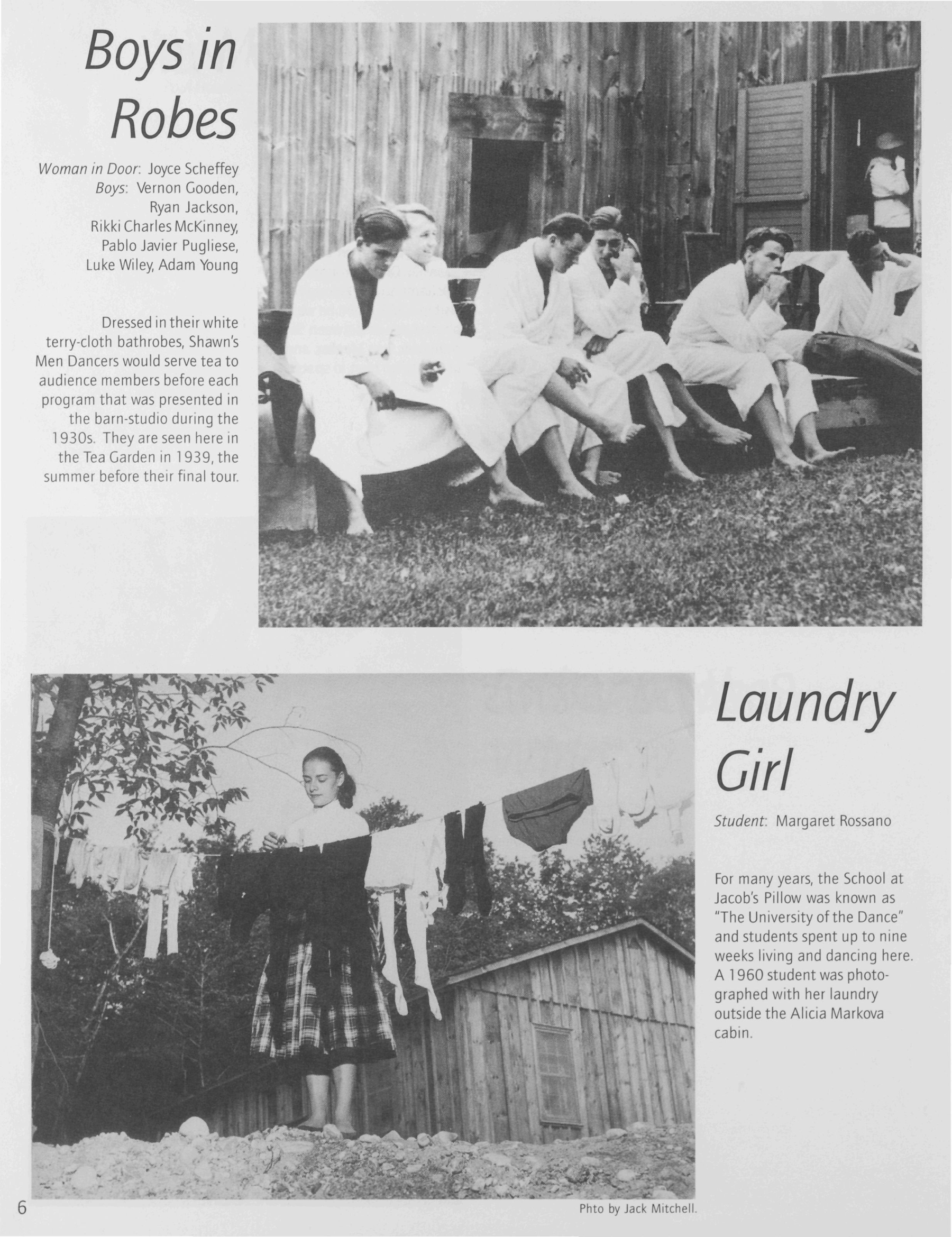

With Night Light (created and presented at the Pillow in 2001), Carlson approached the intersections of choreography and photography. Working from a collection of photographs originally taken at or near each performance site, Carlson presented the audience with the history of a place. Through a series of tableaux vivants, Carlson vivified the lives of the people in an earlier era.

The audience follows a tour, with tour guides narrating the history of various places, each from their own perspective.

Rescaled back to life-size proportion, the staged versions of the photographs do more than induce the spectator to reflect on the historical moments. Rather, as the audience travels, armed with the original photographs to compare with the tableaux, it is almost as if they have spontaneously happened upon those moments occurring.

Carlson does not present these images as ageless icons, with many of them instead possessing a slice-of-life character. But with her attention to accurate historical detail, the tableaux have an enduring quality.

PUBLISHED July 2017