Introduction

Every day during her pregnancy, Twyla Tharp videotaped herself performing the same movement material, documenting her thorough exploration of the ways in which her changing body changed her dancing. This is typical dancemaking by Tharp: at the same time as she is deeply involved in the kinesthetics of the actions, she is also coolly analytical in her observation of the evolving form of each dance from the outside.

Tharp’s Early Career

From early in her career as a choreographer, Tharp was undaunted by conventions that held dance forms apart from each other, compartmentalizing them into distinctly separate ideas. Her own training was wide-ranging. She studied ballet with Margaret Craske; modern dance with Lester Horton, Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Alwin Nikolais, and Erick Hawkins; jazz with Luigi; as well as baton, flamenco, tap, and violin. Despite her familiarity with such a diverse range of dance techniques, what she liked best—and could find at places in each of the different techniques that she studied—was when, as she explained in her autobiography, “the movement had nothing to do with theories or steps but simply burst into space.”Twyla Tharp, Push Comes to Shove. Bantam, 1992. For example, Tharp loved Cunningham’s rigorous technique and rhythmic sophistication, but was unwilling to leave her own choreography up to chance operations. Further, while deeply appreciative of Graham’s choreography, it was not the kind of work Tharp wanted to do. She was uncomfortable with grand narratives and character portrayals. Again, as she says in her autobiography,

I could not picture myself as other than I was—an Indiana farm girl to whom seeds meant plants, not metaphors.”

Tharp and her dancers have always performed in a seemingly offhand manner that makes the virtuosic displays all the more startling. Without a moment’s notice, the dancers seamlessly shift from effortlessly placed arabesques to off-center, shoulder-twitching jumps. Shuffling footwork is replaced by dead-on balances with an extended leg. The foot flexes, and the pelvis spirals downward as the spine carves an upward arc. The hallmarks of the dancing in Tharp’s works are these surprising combinations of movements, as well as split-second timing, complicated rhythms, and intricate spatial arrangements. Tharp has assimilated classical technique into her movement vocabulary, insisting that her dancers have a thorough grounding in ballet, while also being able to ignore it. Tharp wants her dancers to be able to perform multiple pirouettes with exquisite turnout, but she also wants them just as easily to detour unexpectedly into loose-limbed squiggles.

Tharp Discusses Choreography

Unafraid to admit just how challenging her early choreographic expeditions were, Tharp and early dance company members, including Sara Rudner and Rose Marie Wright, often carried around lists of instructions to keep their places in the choreography. The dancers moved with acute mathematical precision, stoic faces revealing nothing about their individual personalities. All those early dances Tharp counts as lessons preparing for her 1970 signature work, The Fugue, which has remained in the repertory, even as she moved on to new challenges.

Like many of her works, The Fugue demands equal parts concentration, intelligence, and physical capability, with the three dancers performing twenty variations on a single movement theme. Tharp delves deeply into the phrase: she inverts it (things that curve up, curve down), retrogrades it (as if running a movie camera backwards), resequences it (varies the order), changes the timing, alters the spacing, makes the phrase travel in all dimensions. While the basic vocabulary of The Fugue is pedestrian, its structural complexities make it quite sophisticated.

Of the dozens of works that Tharp has made, it is possible to point to any number of them to detail the ways in which her work has confronted boundaries in dance, and leapt over them with verve, wit, and style. Dances like Eight Jelly Rolls (1971), Sue’s Leg (1975), Nine Sinatra Songs (1982), The Catherine Wheel (1983), and In the Upper Room (1986) all incorporate and comment on multiple dance styles.

From her early experiments in the 1960s, through the running of her modern dance company in the 1970s and ‘80s, to her forays into the ballet world, first as guest choreographer and then as associate artistic director of American Ballet Theatre, Tharp has been known for her scrupulous logic and commitment to rigorous technique.

Tharp and the Joffrey Ballet

Tharp considers Robert Joffrey’s invitation to make a piece for the Joffrey Ballet the event that pushed her into the mainstream of dance. It may also be said that her choreography pushed the mainstream of dance in a new direction. Deuce Coupe (1973) challenged long-held perceptions of ballet on several levels. First off, Tharp used music by The Beach Boys, picking the slang of her own youth as the vernacular for the dance. The juxtaposition of 20th-century popular music with the conventions of the 19th-century ballet aesthetic was jarring and invigorating to the audiences as well as to balletic vocabulary and form. Further, Tharp interpolated pedestrian movements, like running and tumbling, and interwove snippets of social dance forms, like the mashed potato, into the ballet. Finally, Tharp insisted that a place be made for her dancers to perform in the piece alongside the ballet dancers. This mixing of dancers, modern and ballet, shaped Tharp’s future. It led her to choreograph for American Ballet Theatre, creating important works for Mikhail Baryshnikov, whom she eventually joined as associate artistic director of this important ballet company.

Tharp’s Works for Her Own Company and Others

In addition to bringing her own company of dancers to the Pillow, Tharp’s works have been performed at the Pillow by other companies. In 2001, a collection of community volunteers performed The One Hundreds (1970) under Tharp’s personal direction. In that work, 100 eleven-second movement phrases are performed in sequence by two dancers, and then each phrase is performed by one of the 100 volunteers.

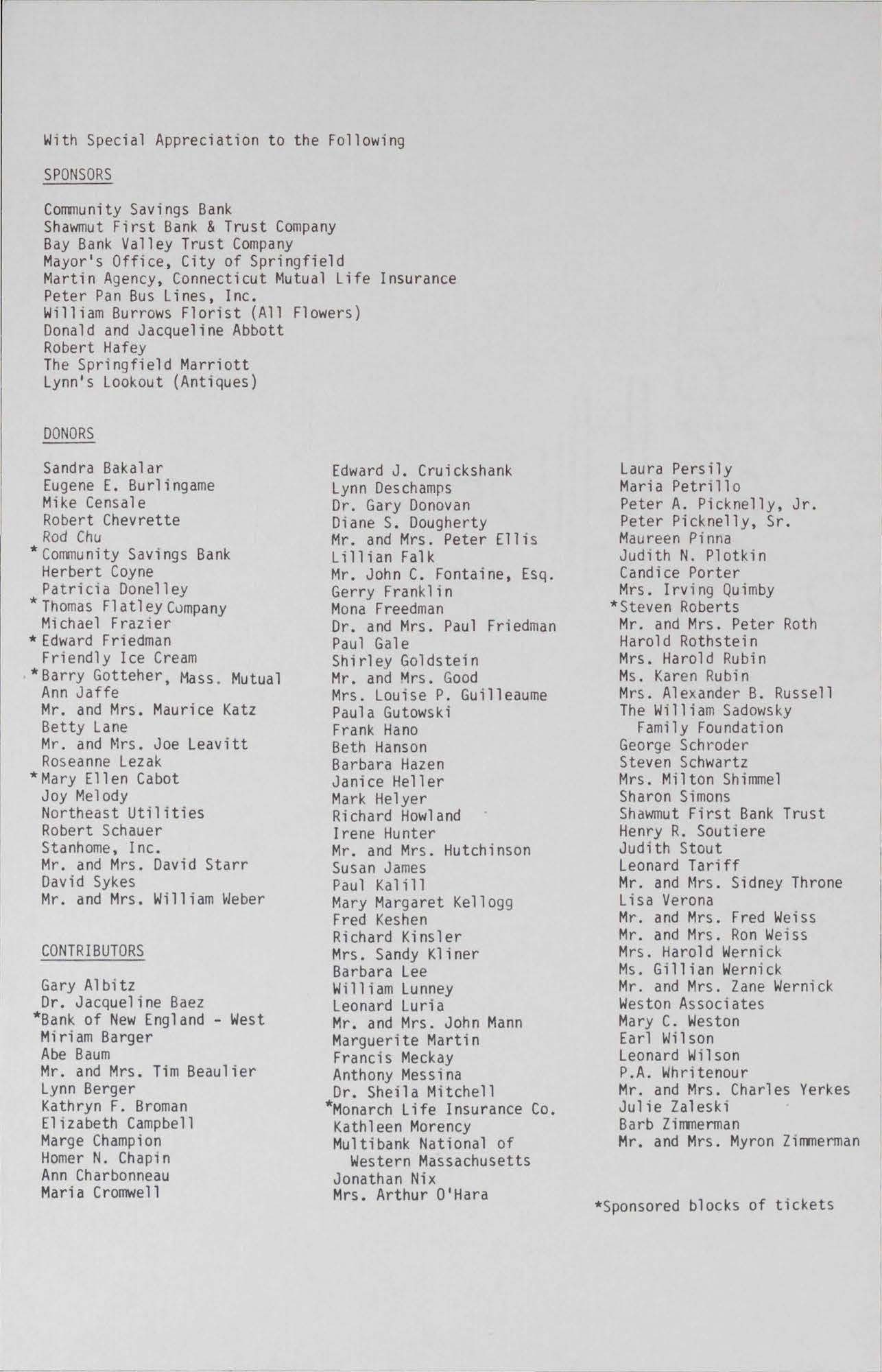

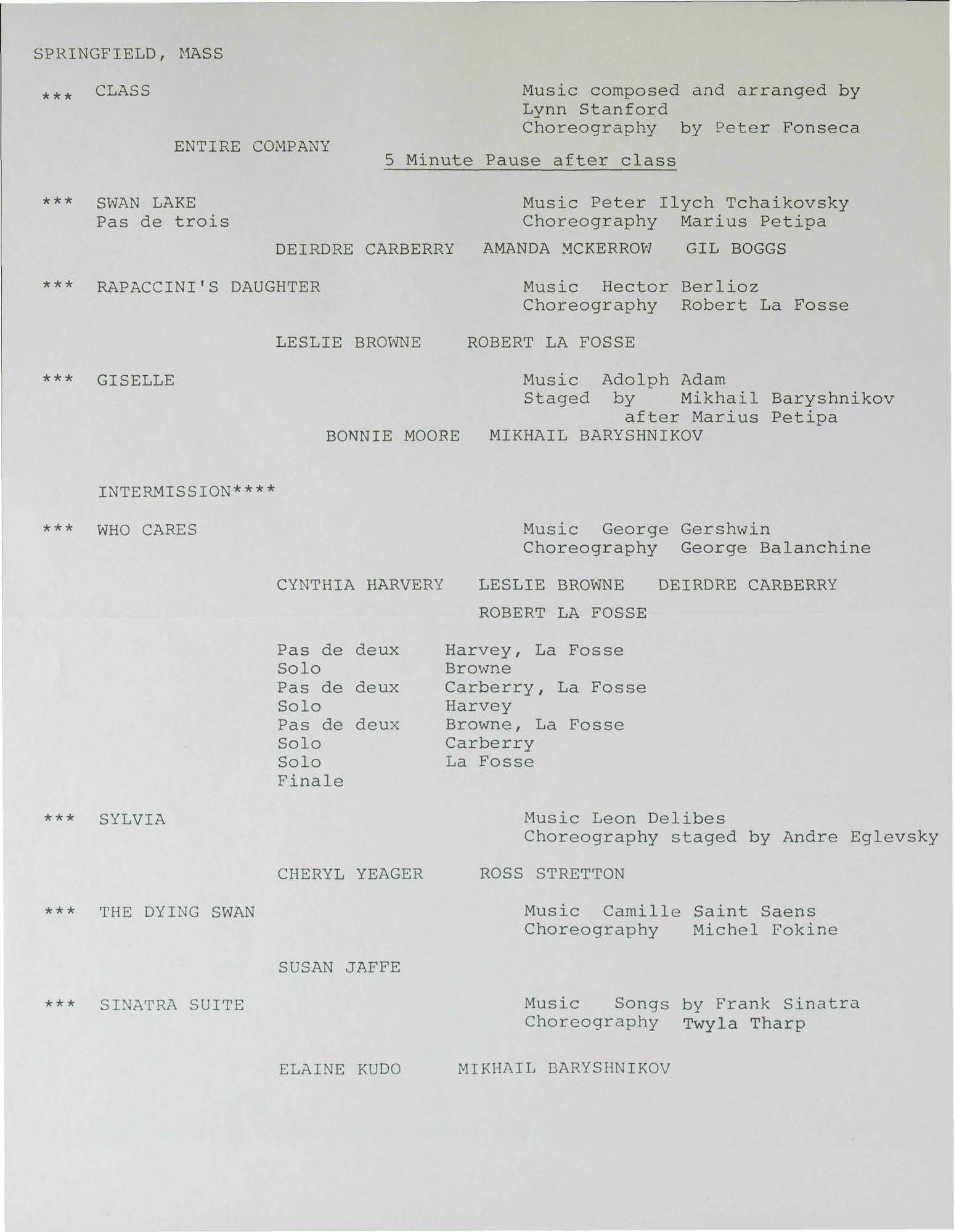

Tharp’s works have also been danced at the Pillow by Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, Aspen Santa Fe Ballet, and in 1985, an ensemble called Baryshnikov and Company performed Tharp’s Sinatra Suite (1983) in a Pillow-produced program at Springfield’s Symphony Hall.

Tharp’s openness to different styles of dance techniques also has always meant an openness to different opportunities for presenting her dances. In addition to her commissions for ballet companies, she and her dancers have worked on films, video and television projects, and commercials.

Tharp was named after a Pig Princess at an Indiana State Fair, so it is only appropriate that she reigns over a whole host of dance styles, seizing what she considers the best and most exciting from all different sources. For Tharp, the movements of dance—the jumps, turns, gestures, and postures—are endlessly intriguing. Just as her body changed during the nine months before her son’s birth, Tharp’s body of work has changed over the five decades of choreographing. Fundamentally, what remains constant is her perpetual fascination with movement, the juxtaposition of different forms, and the complicated structuring of that movement. Not surprisingly, it turns out to be fascinating for us as well.

PUBLISHED March 2017