Introduction

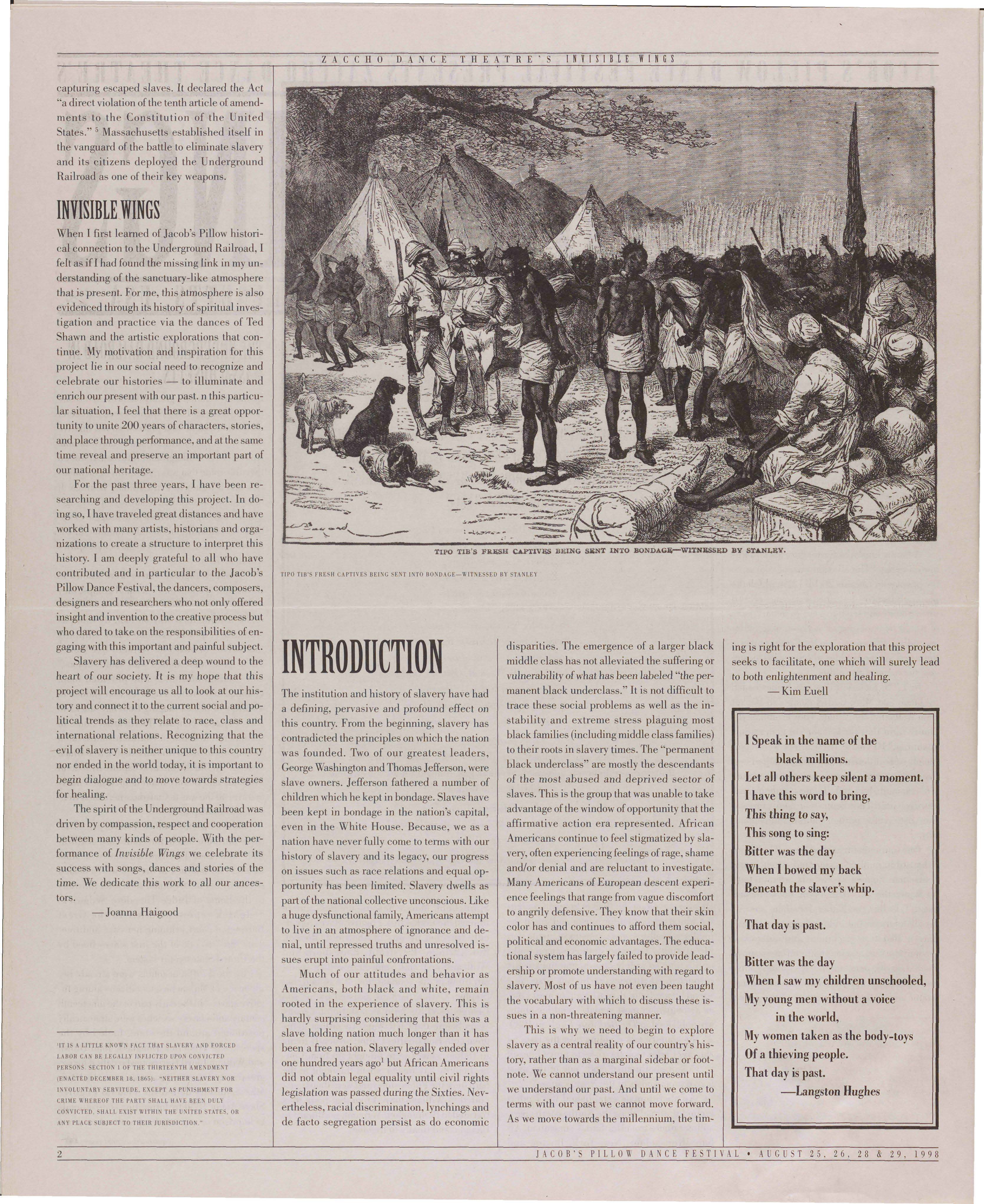

Traditionally, in many dance forms—west African traditions, Greek theater, Indian dance, Native American dance—the performer is seen as a conduit. Art is a creation of gods, ancestors, spirits; art is a way to commune with a consciousness from another time and place. Today we often refer to a ‘muse’ inspiring a human to create. However, in Greek and Roman times the human was the vessel through which the Muse created. Musicians, dancers and theater performers were tools of divination so that we could experience a deeper understanding of the interactions between place, time, and silent truths that inhabit a space. Under the influence of dominant, Eurocentric perspectives that place the artist at the center of their creation as genius and maker, rather than skilled artisan and divinator, dance writing has historically struggled to view the art form in this way. But when exploring the work of Eiko Otake and Joanna Haigood, this distinction becomes unavoidable. Both artists seem to pull dances from the earth of a place, embodying its very essence, and translating one time to another, through their work. The resulting performances are very different. Eiko uses only her own body, whereas Haigood builds work for and with others’ bodies and voices, through her company, Zaccho Dance Theatre. However, there is a common thread of surrender to the work, and to the site itself, that connects them.

Eiko Otake: A Body in Places

In 2011 Eiko Otake, formerly of Eiko & Koma, traveled to Japan to bear witness to the effects of the Tsunami and subsequent nuclear disaster which leveled Fukushima and caused 15,854 deaths (as well as 1,600 additional deaths caused by the nuclear reactor meltdown, while more than 2,500 people are still missing). The experience haunted her and, in 2014, she returned with a collaborator, the Japanese historian and photographer, William Johnston. Prior to this trip, the duo had worked on a project titled A Body in Station, set in Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station. Upon returning from Japan, Eiko and Johnston broached an idea of expanding the concept of A Body in Station to reach beyond Philadelphia. Thus, launched A Body in Places and deepened the meaning and import of the piece for both Eiko and Johnston. The work immediately became a bridge and a vessel to carry the embodied experience of the destruction of Fukushima to other locations around the world. Eiko’s focus on subtle provocation, in the silence of her movement, is meant as a tool for heightened awareness and experience.

A master of Butoh, the Japanese dance/theater form developed in response to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1941, Eiko has devoted her life’s work to augmenting our realities by inserting her body, as a channel, into performative spaces. With this piece, she is even more direct in her disruption.

In a PillowTalk moderated by Maura Keefe, Eiko spoke about what drives her. “Society is like DNA,” Eiko said. “It is born moving forward. I want to say stop.”

Society is like DNA. It is born moving forward. I want to say stop.”

Eiko wants us to pause and think of our lives and actions purposefully, pointing to the irresponsibility of the Japanese government. Noting that the Fukushima area is known for its earthquakes and tsunamis, she makes the point that to build nuclear reactors in regions prone to such natural disasters is highly irresponsible. It is this type of social awareness she wants to ignite through her work.

The work itself carries the emotional resonance of Fukushima, of destruction, and of loss, and brings it to a living, interpersonal, human level. Dressed in an ivory kimono that she wore and danced in while in Fukushima (a kimono that has been tested and carries low, non-harmful levels of radiation), Eiko responds to her surroundings. Her movement is deeply intentional. She wraps her body around a tree, the hem of her garment catches and suddenly she is transfixed, investigating the sapling that holds her skirt. The piece unfolds as audience members walk the grounds, following, stopping when Eiko pauses in a space—at the Pillow Rock, or in a clearing in the woods. She flows between natural objects, scooping water from a large metal bowl, gracefully stumbling backward as if blown by the wind or carried by an ocean current. She is in nature and she is the elements themselves. By placing her body in place, in time, under our gaze, Eiko, as one audience member says at the end of the aforementioned PillowTalk, IS art. “You are not an artist,” the audience member states emphatically to Eiko,“you are art. And art comments on itself.”

You are not an artist, you are art. And art comments on itself.”

Dance, perhaps more than any other form, allows for this when it is permitted. A Body at the Pillow is a raw reflection of Eiko’s experience; without flourish or embellishment, she brings Fukushima to Jacob’s Pillow, opens a passageway and offers a mirror to all.

Joanna Haigood: Invisible Wings

In a 1998 PillowTalk moderated by Maura Keefe, Joanna Haigood described Invisible Wings as a piece she was more “receiving,” than a work she was creating. Begun several years prior, during a site visit to Jacob’s Pillow when she was working on the piece Cho-Mu, Invisible Wings grew from a single line of text she encountered in some promotional materials for the Pillow that were found in the Archives. Invisible Wings grew from a single line of text she encountered in some promotional materials for the Pillow that were found in the Archives. That line indicated that Jacob’s Pillow had been a station for the Underground Railroad, and this immediately captured Haigood’s imagination. As a woman of African descent, she knew that this was an important impulse to follow, one that was as much about discovery and learning as it was about making a performance piece.

So began a years-long journey of listening to stories told by the elderly descendants of the Carter family who had owned the land that is now Jacob’s Pillow. Haigood shares that no one really knew this part of the history of the region in regard to enslaved individuals fleeing their captors. However once she heard enough similar stories from unrelated sources, she had material to piece together, validaing this important part of the Pillow’s history.

She began the process of excavating the dances, stories, and songs that might have been carried in the bodies and souls of enslaved people making their way to freedom through the Underground Railroad. This took her home—to family in South Carolina and to the Sea Islands. There she visited Gullah Geechee communities where language, song and dance has existed untouched for some 150 years, passed down generation to generation, along with the land, by descendants of freed slaves.

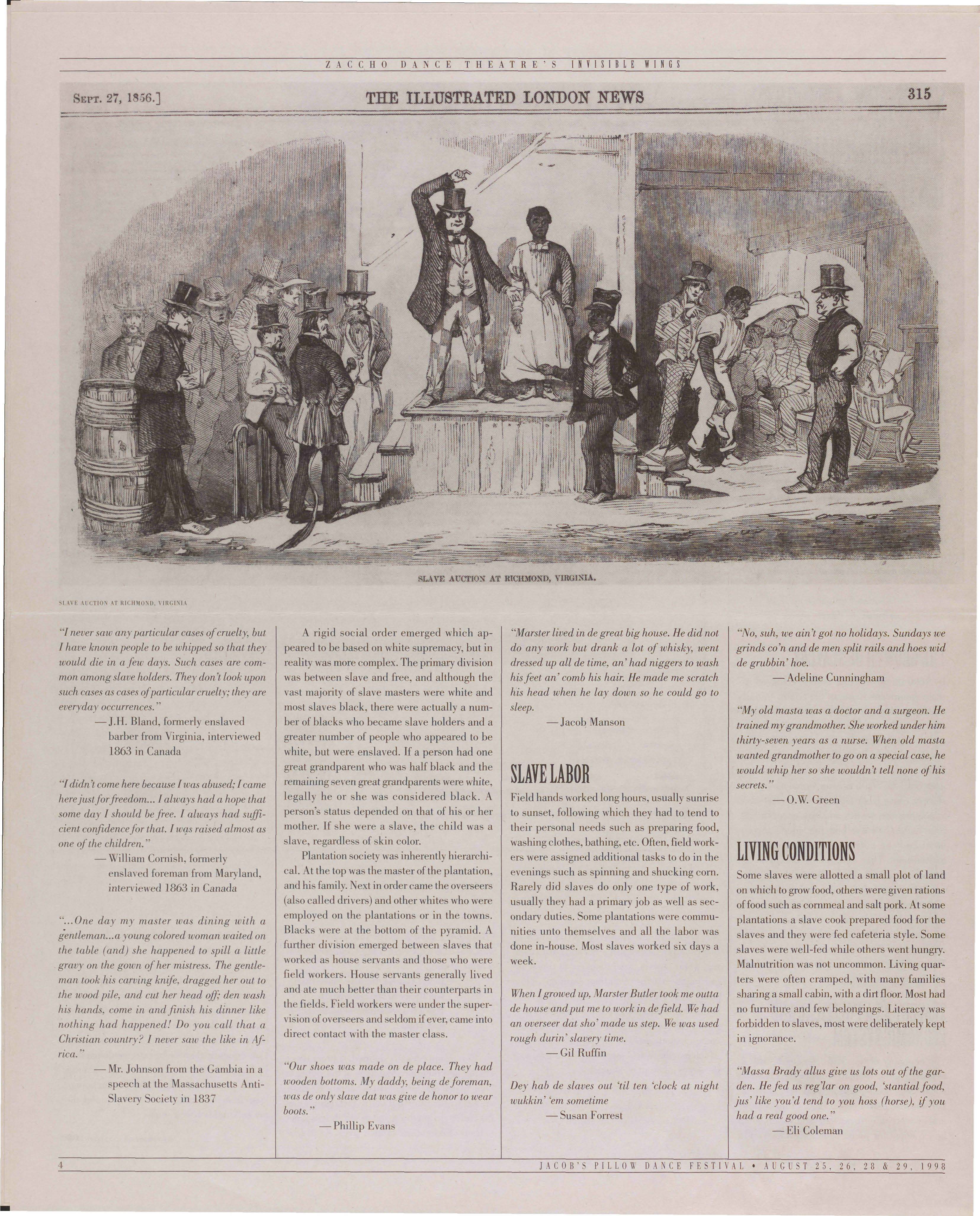

Haigood describes how elders in these communities, even her own uncle, shared traditional dances like the Ring Shout and Snake Hip, movement that, she indicates, is still visible in the Moon Walk and other afro-based pop-culture and hip-hop forms. They also shared Gullah songs and stories with her. This material formed the foundational movement vocabulary along with the narrative and sound score created by storyteller Diane Ferlatte and musician Linda Tillery, respectively.Slavery art, says Haigood, was filled with the purpose of elevating the spirit—it was meant to help transcend the conditions under which they lived. Slavery art, says Haigood, was filled with the purpose of elevating the spirit—it was meant to help transcend the conditions under which they lived. Even the title of the work refers to the narrative and hope that daily burdens would be lifted by spontaneous ascension, through divine intervention. A long-held belief, this is echoed in songs like Summertime with the lyrics, “One of these mornings, you’re gonna rise up singing, and you’ll spread your wings and you’ll take to the sky…” In Invisible Wings, Haigood brings to light and to life history that hangs around us, but needed her gaze for us to truly see.

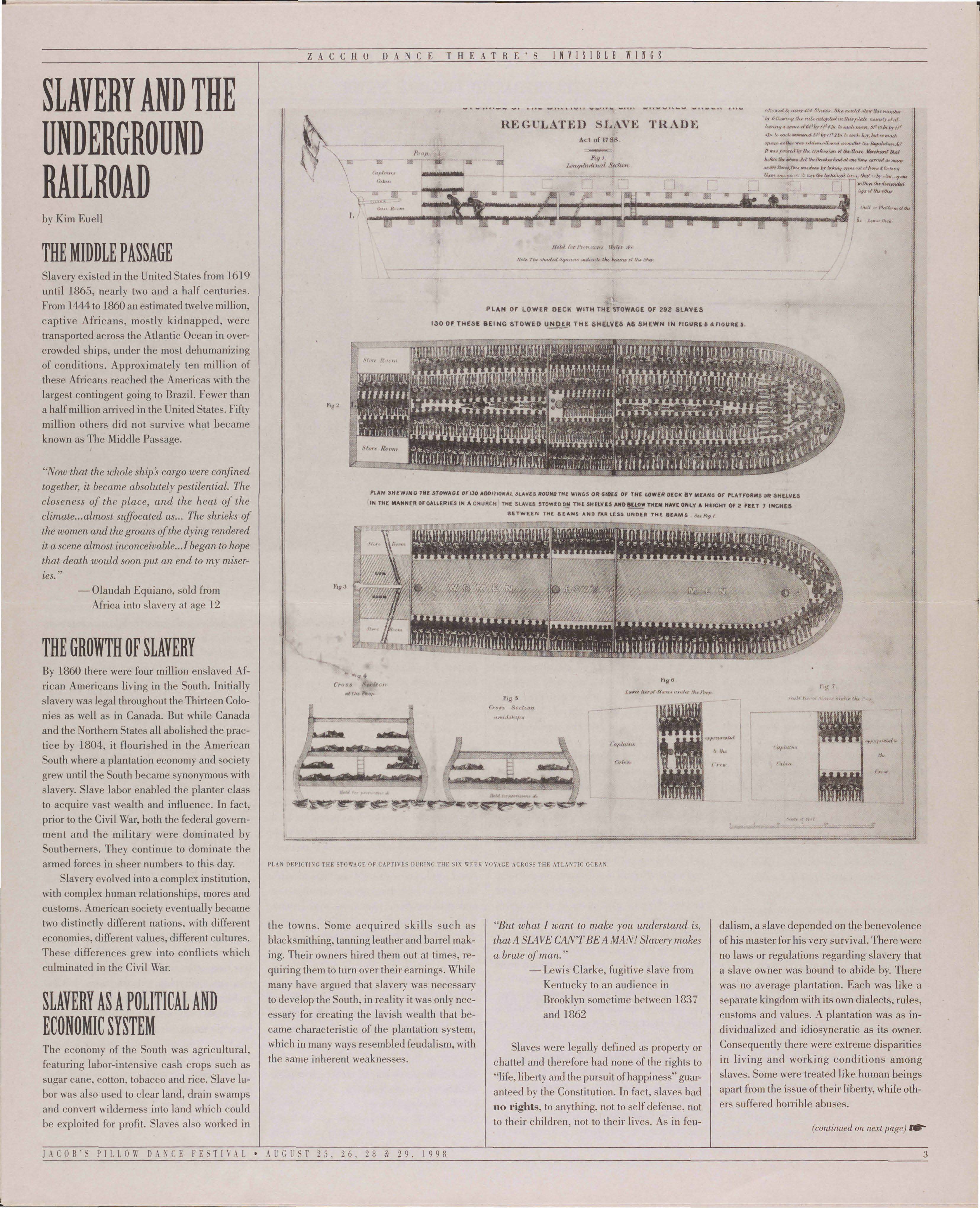

Like A Body at the Pillow, Invisible Wings uses the Pillow grounds as the ‘stage.’ Haigood uses rooftops of houses, an open barn, a flat-bed horse drawn wagon, constructed stages, large flat rocks, the woods and open fields of the Pillow to create a journey back in time. Performers are dressed in period costumes, women in long layered skirts, boots, cotton blouses, and white headwraps. Men wear straight-legged trousers, linen vests and collared shirts. Some men wear coveralls and bare feet. There is a weight in all of their movements; a tension between hope, uplifting and struggle. As audience members journey through the performance, they move from storyteller to singer, and from staged performance in blackface to intimate scenes between family members. As visitors travel, they carry a newspaper that outlines the history of enslaved people in the United States. Vignettes they witness are reflected in the written pages in their hands.

Conclusion

Dance serves an incredibly important role in society, one that is in danger of being lost if we do not declare its utility, when channeled through the artist, to make the unseen, seen. It allows us to pierce the veil, to tap into the emotional resonance of shared, yet sometimes unspoken, human experience—past, present, and future.

Endnotes

Note: In the twenty years since the creation of Invisible Wings, Gullah Geechee communities have been dispersed and this culture continues to fade. The development of resorts, golf courses, and gated communities called ‘plantations’ have overtaken Gullah land and forced the Gullah Geechee people out. Learn more here.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to the following readers: Amy Latimore, Teena Marie Custer, and Matthew Pardo.

Bibliography:

A Body in Places website

Zaccho Dance Theatre website

Statistics for Fukushima

PUBLISHED October 2018