Preface

Latina/o/xThrough this essay I use multiple suffixes and variants to illustrate the ethno-racial and gender complexities of the terms and the evolving usage of the identifier Latino. identity or its cultural expressions—LatinidadPadilla, Felix M. Latino Ethnic Consciousness: The Case of Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans in Chicago. 1st Edition. Notre Dame, Ind: University of Notre Dame Press, 1985. This study is generally considered one of the groundbreaking studies of pan-latinidad in the United States, known for coining the panethnic term latinismo and for its attention to the tension between self-identification and state-ordained labeling., which exist through shared cultural experiences among Latinx people—is complicated by conquest and colonization, resistance, liberation, geography, social class, gender and race, to name a few. It is multi-racialLatina/o/x people may be from any race including white. The U.S. Census Bureau uses the term Hispanic origin and defines it as, “Hispanic origin can be viewed as the heritage, nationality, lineage, or country of birth of the person or the person’s parents or ancestors before arriving in the United States. People who identify as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be any race.” Hispanic is generally considered to refer to anyone of Spanish-speaking origin. This essay uses the term Latino and its variants to identify people of Latin American origin, not only those of Spanish-speaking origin. Latino exists as a multi-racial identifier and also a racialized one determined by cultural attitudes towards a person- “how they are seen”, location of use, geography and histories. For more reading on the 2010 and 2020 U.S. Census two-part question format on ethnicity and race, visit: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/will-2020-census-miss-reality-latino-numbers-identity-n897976 and multi-ethnic and includes Latin America and Afro Latinx and Latinx people within North America, Central America and South America, and the Caribbean and Latinx Indigenous people of these geographies. The existence of these complexities, which are intersectional and deeply nuanced, resist, break, and challenge both the shifting terms of how race is understood in the United StatesThis essay intentionally considers the negotiation of race and brownness in the U.S. and challenge singular ideas of what is meant when a person identifies as Latinx. Historical tactics of exploitation and exclusion against many Latinx people of color have been transformed and further instrumentalized today.Latinx people, if there can even be a singular identity, do not possess a singular narrative of immemorial relationship to land, to home, to freedom, of subjugation, or of resistance and liberation, but many valuable narratives which also intersect deeply with experiences of immigration, migration, violence, and removal from, and occupation of homelands. I personally feel that historical tactics of exploitation and exclusion against many Latinx people of color have been transformed and further instrumentalized today. Parts of this essay were written during the 2018-2019 U.S. government partial shutdown as President Trump demanded more than 5 billion dollars for a U.S.- Mexico Border wall.U.S. Department of Commerce: (December 22, 2018). Retreived From https://www.commerce.gov/news/blog/2018/12/shutdown-due-lapse-congressional-appropriations.

Like the present manifestations of the U.S.-Mexico border, a physical fence running into the Pacific Ocean at one end, a virtual fence in some areas, and a fence topped with razor wire in others, an incongruous boundary, for me, brown as a racialized concept is difficult to trace with consistency and finitude. Each is shaped in part by experiences and sometimes shifting policy. Each is constructed and reconstructed by those living in and moving through and across it. Some friends in my Mexican-American Latinx community instead speak of “the borderlands” and a Mestizo identity—plural, rolling, a complicated idea in motion through history and the present. The term Mestizo means “mixed” in Spanish and is generally used throughout Latin America to describe people of mixed ancestry with a white European and Indigenous background.Stavans, Ilan. “The United States of Mestizo.” National Endowment for the Humanities, 2010, www.neh.gov/humanities/2010/septemberoctober/feature/the-united-states-mestizo. Mestizaje identity, meaning “mixing or blending” can be an acknowledgement of multi-ethnic rootsAnzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands: La Frontera, San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999, Second Edition. Print. or, an example of policies enacted by governments and attitudes to promote a unified identity that elevates European lineage and intentionally invisibilizes specific Indigenous, African, or Black people and their cultures.Champagne, Duane. “Indigenous Nationalities and the Mestizo Dilemma.” Indian Country Today, 8 Aug. 2017. https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/indigenous-nationalities-and-the-mestizo-dilemma-Y6i-GobMUkymt1lG9bM5ZA/, Accessed 14 Feb. 2019. As Taunya Lovell Banks also writes, “Contemporary anti-black bias in Latin American countries like Mexico is a vestige of Spanish colonialism and nationalism that must be acknowledged, but is often lost in the uncritical celebration of Latina/o mestizaje.”Lovell Banks, Taunya. Mestizaje and the Mexican Mestizo Self: No Hay Sangre Negra, so There is No Blackness. U of Maryland Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2005-48 Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 199-234, Spring 2006.What’s deeply valuable here are the continuing practices of understanding personal connections to language, evolving usage, and the experiences of those within communities represented by the language so as to work together to not reinscribe colonial oppression.

When I speak of a personal Latinx identity, language is a difficult starting point; to know how to identify and articulate living Latinidad, or, “brownness”—particularly in dance works in the full expansiveness of its possibilities. Acknowledging the inter-racial, inter-cultural complexities in attempting to celebrate and embrace brownness is one strategy as well as holding space collectively for the expansiveness and in-between-ness—or multitudes of Latinidad as it shifts and unfolds, moving through modes of recognition or challenging them, or sometimes refusing them, and back again, as artists and dance makers make and (re)make its many manifestations.

Introduction

Works presented over many years by choreographers of Latin American descent may be found in the Jacob’s Pillow Archives. The collection includes the work of José Limón who performed at the Pillow several times since 1946, Manuel Alum in the 1970s and ’80s, and more.

Still, Latinx artists are under-represented in proportion to Latinx peoples in the U.S. and those making dance.This is important to note as in 2016 Latino people comprised 18% of the U.S. population. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/

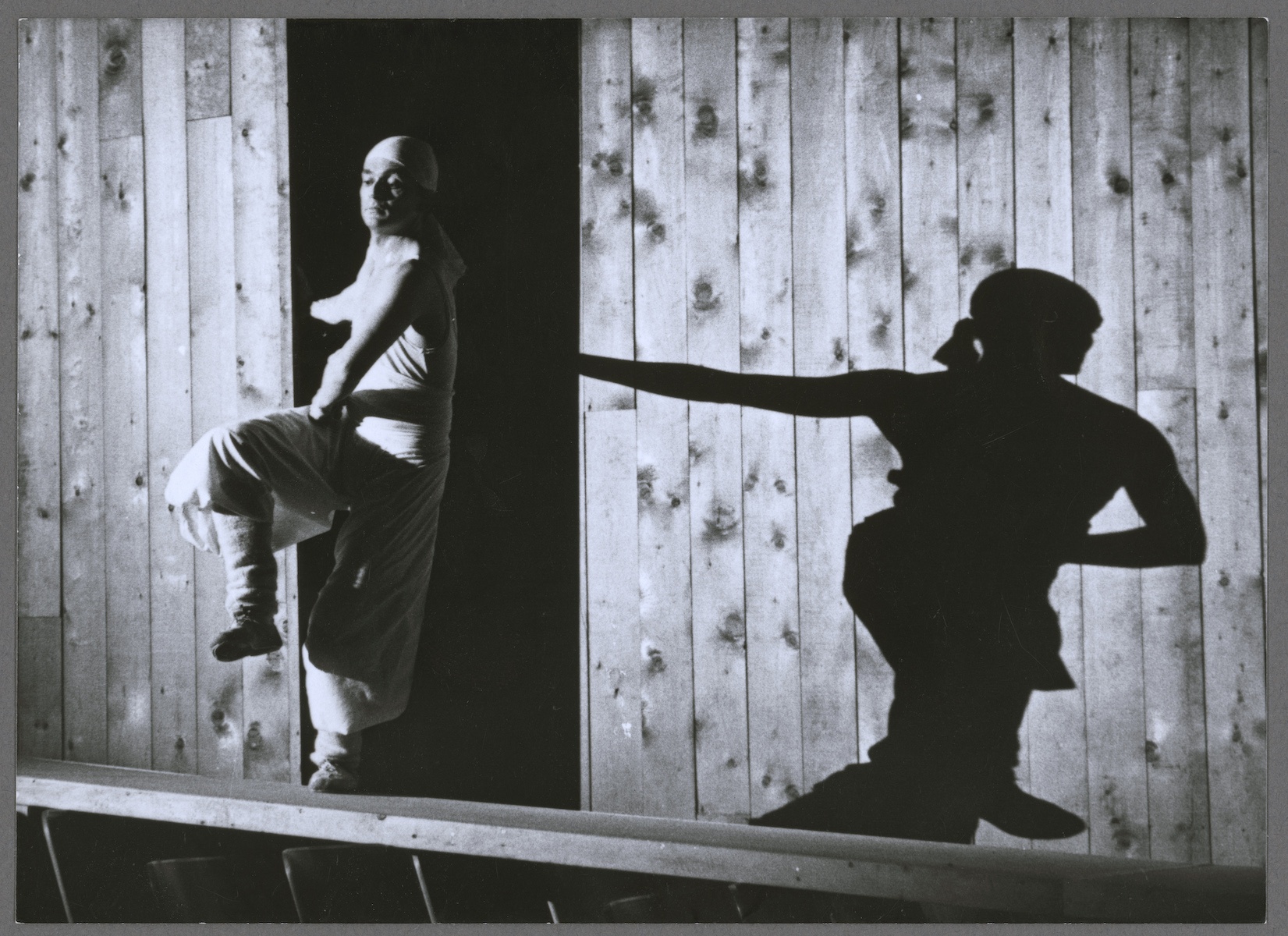

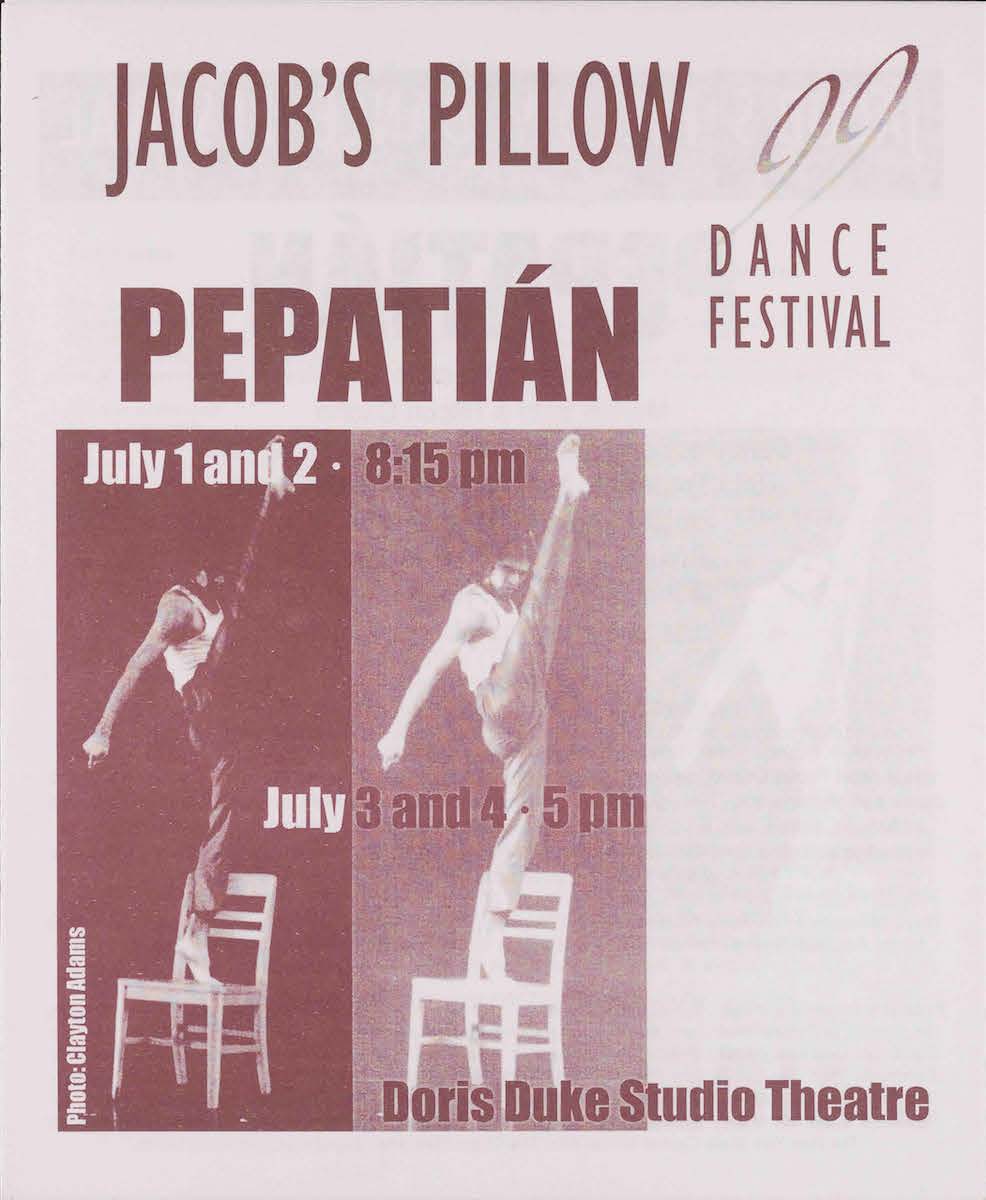

The late 1990s and 2000s were a vibrant time of artists of color embodying resistance and visibility through dance and other art forms in popular culture. I look on this time fondly as a person whose formulations of racial belonging and possibility began to take shape then as a teenager. In 1999 Merián Soto presented a program of her work at Jacob’s Pillow blending styles of Salsa and Afro Caribbean rhythms. The program was an evening of three performances that included dancers Sonny Allen, Gina Benitez, Niles Ford, Sita Frederick, Antonio Ramos, Ivan Rivera, Noemí Segarra, and Stephanie Tooman. It reflected an exploration of gender dynamics within Afro Caribbean dance styles with a Nuyorican aesthetic.

Later, in the 2000s, Jacob’s Pillow featured work with choreographers such as Victor Quijada and his Montreal-based RUBBERBANDance Group blending break, ballet, and dance theater.

I have tried through my research in the Jacob’s Pillow Archives to determine a uniting device between the 1999 performance of Sacude and the 2009 performance of Punto Ciego which are vastly different in concept and scale, yet each deeply valuable in its own right. For me, that device is time viewed through the lens of Latinidad which may be perceived clearly in the works or a subtle presence perhaps only perceptible to people sharing these affinities—a recognition of the Latina/x/o cultural attributes which informed the maker and/or the work. Each of these works in the Jacob’s Pillow Archives captivated me years after they were performed. It is exciting to consider the continued development of the artform and the field through these performances and others, over ten years on the same stages, in distant conversation, integrating and negotiating histories, dance lineages, form, and content that reflect the makers and also the complexities of intersectional and limitless identities. I hope that this is an invitation to be captivated also, and to further consider dance, the functions of archives, and how people of color have always been foundational in the development of dance and movement culture.

Merián Soto’s Sacude (Shake) and Self-Empowerment

Pepatián is a South Bronx-based arts organization, co-founded by choreographers Merián Soto and Patti Bradshaw and visual artist Pepón Osorio in 1983. Its mission in 1999, outlined in the performance program reads, “dedicated to creating, presenting, and supporting multi-disciplinary Latino dance and performance”.Printed performance program from Jacob’s Pillow Archives for Pepatián. Merián Soto & Pepón Osorio, Artistic Directors. Performances by Sonny Allen, Gina Benitez, Niles Ford, Sita Frederick, Antonio Ramos, Ivan Rivera, Noemí, Segarra, Stephanie Tooman, Chucho Valdés and Iraquere. The organization continues today under the leadership of Jane Gabriels with a mission of creating, producing, and supporting contemporary multi-disciplinary art by Latino and Bronx-based artists. Pepatián served as the conduit for the 1999 program at Jacob’s Pillow presenting Merián Soto’s work, which included three pieces.

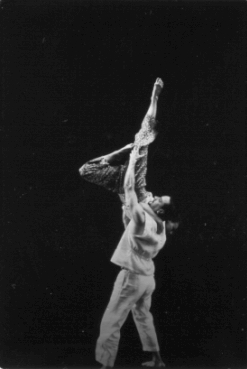

Soto’s first piece of the evening, a 15-minute long performance titled Sacude(Shake) illustrates a visceral energy of the moment, combining social dance and improvising on Salsa rhythms to bring about a palpable infectious energy. In it, dancer Noemí Segarra sings “Atrevimiento” accompanied by Chucho Valdés, founder of the renowned Cuban band Iraquere. The set, designed by Soto in collaboration with installation artist Pepón Osorio, is a series of five portraits of handsome men smiling, all with a particular suavecito-charm within stylized picture frames. Valdés begins to play the piano solo only after Segarra sings the introduction. About this choice, choreographer Merián Soto says, “In having the female dancer sing the words herself, without the accompaniment of musical instruments, the meaning shifts. It becomes a dance of self-empowerment and liberation from sexist norms, and I would add, musicalist colonizing of dance.”Merián Soto. (personal communication, October 25, 2018) The performance begins with an expression of a spirit of resistance and strength of women of color through voice.

1990s Crossover

The spirit and quality of Sacude is also a reflection of a ’90s attitude of visibility of people of color and powerful Latina/x, Afro Latina, and Black women leads in pop culture. First developed as an improvisational solo for Soto in 1989, Sacude was first performed in 1990 and developed theatrically over the years. The 1990s also witnessed the rise and devastating loss of the Queen of Tejano Music, Selena Quintanilla (1995), played by Jennifer Lopez in the 1997 biopic Selena, the release of the record-breaking album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), and also a feature-length film about the Buena Vista Social Club (1999) aimed at resurrecting the music of pre-revolutionary Cuba, featuring Cuban singer Omara Portuondo, which has been described as a crossing-over of Latino culture into mainstream U.S. popular culture. This crossover phenomenon is also mentioned in Maura Keefe’s pre-show talk on the program in 1999, as she articulates, “a real fascination with Latino culture that’s crossing cultural boundaries and divides.”Keefe, Maura “Pre-Performance Talks, July 2, 1999, Tape 1, 1999/06/24-07/07. Much of the dialogue here around this ’90s cultural moment is embedded in a discourse of crossing-over of Latino culture into mainstream culture.

What the ideas of crossing-over fail to recognize is that mainstream culture in the U.S. is built upon a composition of multi-racial, pan-ethnic identities, people, and their contributions. Contributions by Latina/o/x peoples, Black, African American, Afro Latinx, and Afro Caribbean people continue to play foundational roles in the creation of and remaking of Salsa and hip-hop music among other forms of popular song and dance. It is especially important to note the implied distinction between Latino and mainstream in the idea of crossing over. Here, Latino is racialized, and represents a specific grouping of cultural contributions made by Latina/o/x peoples from various geographies including the U.S. These ideas work to both perpetuate the idea of a singular U.S. American culture, and also make invisible the contributions made by artists of color to the cultural fabric of the U.S.When discussed in comparison to the idea of a singular mainstream U.S. American culture, which can be crossed-over-into, and whose members can feel fascination for Latino culture, “mainstream” becomes coded as non-Latino of color and/or white. More broadly, it also creates distinctions between the influences of folk dance on popularized forms and mainstream dances, which make it difficult to fully hold and consider the overlap, evolution, and deep connections between them. These ideas work to both perpetuate the idea of a singular U.S. American culture, and also make invisible the contributions made by artists of color to the cultural fabric of the U.S. and its territories, such as Puerto Rico in this case. In her talk, Keefe also mentions the popularity of the Rumba in the 1920s and the Mambo in the 1950s, noting the impact of these forms within popular U.S. culture’s past.

The live band playing from behind a sheer scrim recalls the lively environment of a neighborhood street, making it part of the history of live accompaniment at Jacob’s Pillow and also part of the legacy of neighborhood street music, reflecting its power and importance as part of the cultural fabric of Latina/o/x communities and life. The music combined with the improvised Salsa movements, incorporating shaking and singing, is a signature of Soto’s style of incorporating form, content, and structure. The feeling of communication from solo performer to audience transcends the concert-dance structure, drawing the audience in and taking them through a journey of emotions along with Segarra. Here, the integral role of storytelling is featured not only verbally, but also through movement and music, as well as spoken text.

Using Osorio’s intimately-crafted Nuyorican BaroqueOsorio’s aesthetic is referenced in the following article: Anna Indych (2001) Nuyorican Baroque: Pepón Osorio’s Chucherías, Art Journal, 60:1, 72-83, DOI: 10.1080/00043249.2001.10792052 style and Merián Soto’s choreographic skill and expression, Sacude articulates a resounding timeless moment of liberation for all those witnessing it, even experienced nearly twenty years later through the Jacob’s Pillow Archives. Through the sentiments of Sacude carried exquisitely through Soto’s concept and choreography, the audience is united in a shared experience with Segarra’s experience on stage. This union comes to life in the final moments of the work when she extends her hand, spins, and makes one final charged motion with her body gesturing upwards. The remaining portraits then fall to the floor together and the audience erupts in applause. Soto explains further about her set design choices, “The pictures of “papitos” in overly decorated frames gave the piece a visual frame that translated the message of female liberation and self-empowerment.”Merián Soto. (personal communication, October 25, 2018) This liberation is foundational to understanding the decade in which the work was made and how dance made by women of color continues to create moments of self and collective empowerment.

Innovation of RUBBERBANDance Group

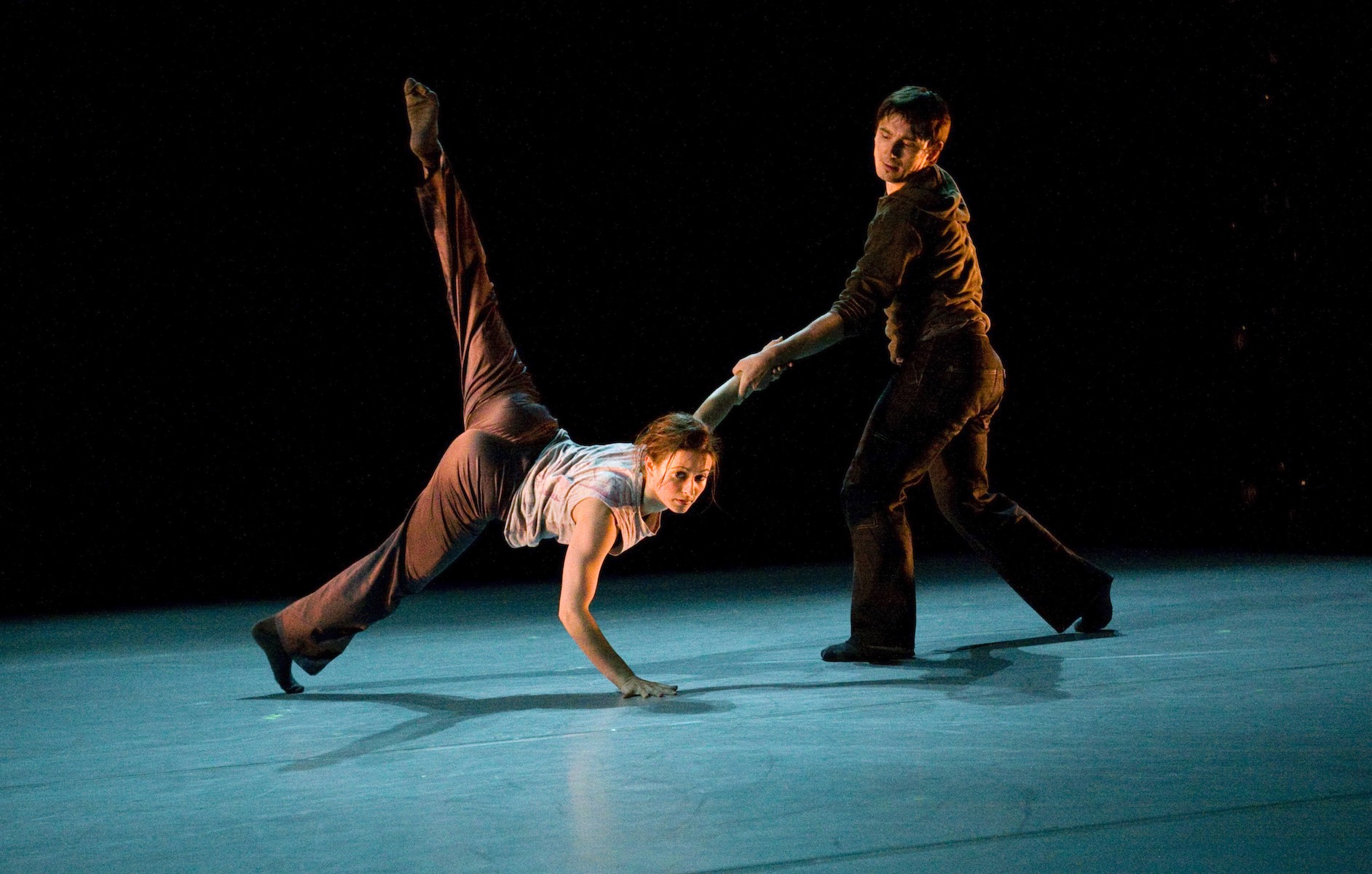

Like Sacude, work presented at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in the early 2000s showcased productions highlighting cultural attitudes and shifts, sometimes subtly. Montreal-based RUBBERBANDance Group’s Punto Ciego, choreographed by Victor Quijada in 2008 and performed at Jacob’s Pillow in 2009, is a journey through a non-linear narrative which shifts focus rapidly from self to others. At its core is a preoccupation with a collective reality that is constructed by the six dancers—Louise Michel Jackson, Mariusz Ostrowski, Anne Plamondon, Victor Quijada, Lila-Mae G.Talbot, and Frédéric Tavernini—just as fast as it is coming apart. Quijada’s choreography is a fluid blend of neo-classical ballet, hip hop, capoeira, break, and postmodern dance, operating as a style uniquely the company’s own. A former student of Rudy Perez—one of the early contributors to Judson Dance TheaterJanevski, Ana and Thomas J. Lax, The Museum of Modern Art, Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done. Edited by Sarah Resnick (New York, NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018, Exhibition Catalog.—Quijada’s movement style is distinct and includes a simple certainty of everyday movement with the explosive energy of hip hop street dance.

Quijada, with co-artistic director Anne Plamondon, weave together a loose and jagged tragicomedy which is both a product of the 1990s and also forward-looking. Punto Ciego’s total running time is 80 minutes and throughout uses the form of a confessional talk show, which grew dramatically in popularity in the 1990s and 2000s. Ahead of its time, through its strategic use of video and narrative, the dance also hints at the destabilizing nature of social media on concepts of self and personal relationships.

You Are the Next Participator

Influenced by his early days dancing in the hip-hop and breakdance cyphers of Los Angeles, Quijada’s performances often include the audience in a participatory role. Noting this early influence in the post-show talk for Punto Ciego, he says, “as a spectator, you are also the next participator.”Post Show Talk, 3961: RUBBERBANDance Group, 2009/08/14, camera angle: mix

The piece concludes with a presumably younger Quijada guiding the audience through a meditative exercise via video while Quijada onstage negotiates both a present and former self represented on the screen. This dividing of selves calls to mind both defiance and conformity, past and present lives, and the tensions in self-representation—what we choose to make visible, and what we choose to conceal. In Punto Ciego, RUBBERBANDance Group journeys through all of these, drawing a constant dynamic connection to the audience. This connection is most keenly felt in these final moments of the work.

Quijada’s movement style feels distinctly migratory to me. It’s worth noting that he moved from his hometown of Los Angeles to New York City then to Montreal and has developed the RUBBERBAND method, which blends the urban street dance styles Quijada came to know in his youth with multiple forms of contemporary dance performed traditionally on stage. He has been credited with “opening the stage to street dance,” and has been breaking down barriers between these dance styles and forms for more than 15 years.

For me, the company’s amalgam of precise techniques offers a story of migration of person(s), of dance training, and of artistry, where ethnocultural experiences and places are partnered in the evolution of place, identity, and style.

Conclusion

Latina/o/x contributions to dance, those perceived as traditional or experimental and those beyond, which are influenced by pan-ethnic cultural forms and featured on the Jacob’s Pillow stage, have been and remain vital to the dance community at large and the health of its ongoing ecology. Here, I am left with my own questions, which inevitably speak to a personal hunger. Where can we trace our own internal dance understandings to? How can we understand in ways that do not reinscribe the lines of colonization upon form, style, and body? And how can these understandings also welcome the refusal of definitions and transcend toward the spaces between? The dance field must include support for more Latinx dance makers and must welcome the full spectrum of possibility for articulating our individual as well as collective Latinidades.