Introduction

In 1993, photographer Philip Trager and choreographers Eiko & Koma collaborated on a series of portraits taken on the grounds of Jacob’s Pillow. The Pillow has a rich history of capturing images of dancers in the fields and among the trees, starting with Pillow founder Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers leaping off rocks and Ruth St. Denis clothed in great swathes of fabric against a Berkshire blue sky. Artists of all sorts have been inspired by the landscape of the Pillow.

As Trager recounts in the wonderful book titled Eiko & Koma: Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty, the Pillow commissioned the artists to provide an opportunity “to engage in a true collaboration, the three of us endeavored to create something unique and new.” Trager goes on to explain,

Even before I started photographing them, I knew that we were totally attuned to one another, that everything would work out beautifully. The day before I arrived, Eiko & Koma chose locations for our session. I then chose some myself. From the myriad possibilities at Jacob’s Pillow, we had selected exactly the same sites.Philip Trager, “Collaborating with Eiko & Koma.” Eiko & Koma: Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2011).

In keeping with Eiko & Koma’s exploration of natural surroundings as both source and site for their choreographic work, they posed nude, in January, at various sites around the Pillow grounds. In the photographs, which are housed in the Pillow Archives, their black hair and pale bodies etch distinct shapes against the dark trees, harsh granite, and burnished snow.For an in-depth consideration of Eiko and Koma’s career, see Pillow Scholar Suzanne Carbonneau’s essay, “Naked: Eiko & Koma in Art & Life” in Eiko & Koma: Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2011).

While their collaboration on the grounds of Jacob’s Pillow resulted in photographs, it was not the last time Eiko & Koma would appear on site, nor are they the only artists who have responded choreographically to the landscape. The Pillow’s natural environment has inspired several choreographers who have collaborated not only with other artists but also with the site itself to make work, such as Joanna Haigood, Ann Carlson, and Pilobolus. Despite the starting place of the grounds of the Pillow, the artists are very different from each other, thus their works are very different.

Site-Specific Dance

In their introduction to Site Dance: Choreographers and the Lure of Alternative Spaces, editors Melanie Kloetzel and Carolyn Pavlik suggest that there are worlds that live within the notion of “site dance,” including works inspired by the site, works that adapt the site to suit the work, and works that have been adapted to fit the space.Site Dance: Choreographers and the Lure of Alternative Spaces, ed. Melanie Kloetzel and Carolyn Pavlik (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013) In addition to artists who made work inspired by the site of Jacob’s Pillow, there are also numerous works that have adapted the theater or the grounds to suit a performance. In this essay, I consider three Pillow site-specific works. In a related essay, I discuss several site-adapted works and their impact on the relationship between the artists and the audience.

One of the best-known site-specific works to occur at Jacob’s Pillow was Invisible Wings choreographed by Joanna Haigood.

Prior to conceiving of and beginning her research for Invisible Wings, which drew on the cultural history of the Pillow and its pre-history as a stop on the Underground Railroad, Haigood explored the physical environment of the Pillow in collaboration with visual artist Reiko Goto. Cho-Mu (1993), also known as CHOMU, was an installation on the grounds of the Pillow inspired by life cycles of butterflies and performed by ZACCHO Dance Theater. Haigood describes the work as a metaphor.

Cho-Mu, which translates loosely from Japanese as “butterfly dreams,” uses movement and naturally occurring elements such as common urban butterflies and their host plants to suggest a metaphorical relationship between human growth and spiritual evolution. With an original score by Chicago composer Lauren Weinger, the work highlights the butterfly’s metamorphosis as a transformation common in our everyday environment yet hidden amidst the distractions and fast pace of 20th century urban living.Joanna Haigood, “Cho-Mu (butterfly dreams)” https://www.flickr.com/photos/zaccho/10754440275

Dancers float and swim, appear and disappear, walk on stilts, and emerge unexpectedly, as the audience walks from station to station.

To read more about Haigood in the context of Black Dancers in the Berkshires, see John Perpener’s essay in the Dance of the African Diaspora section.

To read more about Invisible Wings, see the essay on Haigood in the Women in Dance section.

Choreographer and dance writer Gus Solomons jr. wrote about Cho-Mu when he was contemplating site works for New York Public Library’s blog. In that piece, he reflected on works he has choreographed as well as on the works of others. He wrote:

When my company and I began doing dances outside of theaters, I called them “environmental” dances. That is, they were performed in alternative kinds of locations that were not conventional concert dance venues. Not all those works were site-specific. Some of them could be described as site non-specific: that is, they could be adapted to various locations rather than requiring a single, specific place.Gus Solomons jr, “Everybody’s Guide to Gus Solomons jr’s Dances for Alternative Spaces” May 4, 2016 https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/05/04/everybodys-guide-gus-solomons-jrs-dances

Night Light (2001) is an intriguing example to consider of a site non-specific work, to use Solomons’s term. For Night Light, performed at the Pillow in 2001, choreographer Ann Carlson adapts the work not only to the site, but also to the people who occupied the place in the past. A series of tableaux vivants that stage historic black and white photographs in grey scale, Night Light requires the performers to remain motionless while the audience walks from place to place on the grounds. While the environment is important to her work, in this case, it frames the action of the people. (For further discussion of Carlson’s work, including moving images and interviews, please read the essay on Carlson in the Women in Dance section.)

Pilobolus

The collaborators of Pilobolus, like Joanna Haigood for her piece Cho-Mu, have found great inspiration in the environment itself, especially for a Pillow commission in 2017. Since its inception in 1971, Pilobolus has been making works with an ethos of shared creativity, sense of fun, and physicality. Ora Brafman, writing in The Jerusalem Post, commented, “The company’s spirit thrives on curiosity, imagination and perfection, spiced with some tongue-in-cheek humor.”Ora Brafman, “DANCE REVIEW: PILOBOLUS” January 27, 2016 Jerusalem Post https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Culture/DANCE-REVIEW-PILOBOLUS-442977

It is exactly that sense of inquisitiveness that led Pillow Director Pamela Tatge to commission Branches for Inside/Out from Pilobolus to kick off the Pillow’s 85th Anniversary season. Tatge believes that part of her role as director is stewardship of the Pillow’s grounds and is committed to working to sustain its special nature, both inside the historic buildings and within the surrounding landscape. In anticipation of their work for and around the outdoor venue, Pilobolus made multiple visits to explore the site. That meant running around the grounds in a snowstorm, digging in the Pillow Archives, and investigating the stage and setting of Inside/Out. Part of the challenge for anyone dancing on Inside/Out is the lack of control over elements that in a theater would ordinarily be managed—especially the weather.

For Pilobolus, a particularly important collaborator for the commission was the space itself. As Itamar Kubovy, Pilobolus’s executive producer, said in an interview, “the parameters of the commission are such that we’re really engaging not just with ourselves in the context of the Pillow, but engaging with the Pillow physically—the stage, the environment… using this place as our inspiration.”

Part of the inspiration was certainly the physical landscape, but it was also the historic landscape the company found inspiring. As Kubovy said, “This is about a place, the people, the conversation, the purpose, and American dance is…very circumscribed. American modern dance is a thing. It’s a historical art form that’s American, and I think that, more than any other place in the country, this place…feels like it’s the temple for that art form, so it’s cool to kind of be able to contribute something to the temple of your art form.”

Like Philip Trager, in collaboration with Eiko & Koma, Pillow photographer Christopher Duggan was inspired to collaborate with Pilobolus on a series of photographs in a variety of natural atmospheres of the Berkshires.

Eiko Otake

In 2017, longtime partners Eiko and Koma returned to the grounds for two very different, individual performed site-specific works.

After working as Eiko & Koma for more forty years, Eiko Otake, a movement-based multidisciplinary performing artist began her solo project, A Body in Places, with A Body in a Station, in 2014. How the project manifests depends on location, scale, and manner of presentation; A Body in Places is unique in each iteration. Eiko conceived the project when Harry Philbrick, then Museum Director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), invited her to perform a 12-hour durational work in Amtrak’s 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. To make a strong contrast to the majestic and busy terminal, Eiko wanted to posit her body in very different places which led her to think about to Fukushima. This resulted in another part of Eiko’s project, A Body in Fukushima, a collaborative work between Eiko and photographer William Johnston.Fukushima is a shorthand for the nuclear disaster at The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Fukushima, Japan, following a massive tsunami on 11 March 2011. The tsunami slammed into the coast of Japan, killing more than 15,000 people and destroying or damaging more than a million buildings. The Japanese government ordered the evacuation of everyone living within 20 kilometers of the site.

In addition to her performance on the grounds of Jacob’s Pillow, Eiko also presented A Body in the Library at the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield, and offered a pop-up performance at Third Thursdays, also in Pittsfield. In a PillowTalk, Eiko talked about adapting her work to the variety of locations, noting that she responds to the innate characteristics of each specific place. She went on to talk about recognizing what she can control and what she cannot.

Koma Otake

One of the reasons Eiko began her explorations as a solo artist was because of a career-suspending injury that Koma Otake had suffered. While injured, Koma began to paint, fearing he would never be able to move fully again. As he recovered, and began to move more fully than he anticipated, he developed The Ghost Festival (2016), a dance/art project. For each iteration of The Ghost Festival, Koma arrives at each new performance site with a Jeep pulling a trailer, and he alone prepares the site and performs. To use Solomons’s term, one can consider this a site non-specific dance. Koma has performed it in places as different as New York City and on Martha’s Vineyard, in settings such as a ballroom and in a churchyard. At the Pillow, as audiences left theaters after performances, they happened upon the dance in the middle of the grass.

Because of the power of Eiko & Koma’s creative partnership, one might be surprised by the impact of their individual works. Judy Hussie-Taylor, executive director and chief curator at New York’s Danspace Project, commented in the New York Times that she had been watching the two of them dance for the past 40 years. She went on to say, “I guess the assumption is you might be diminished without the other,” she said, “but I feel like the opposite happened with each of them. It’s unleashed something else.”Gia Kourlas, “Koma Alone (Except for All the Dancing Spirits in the Room).” New York Times, May 9, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/09/arts/dance/koma-alone-except-for-all-the-dancing-spirits-in-the-room.html

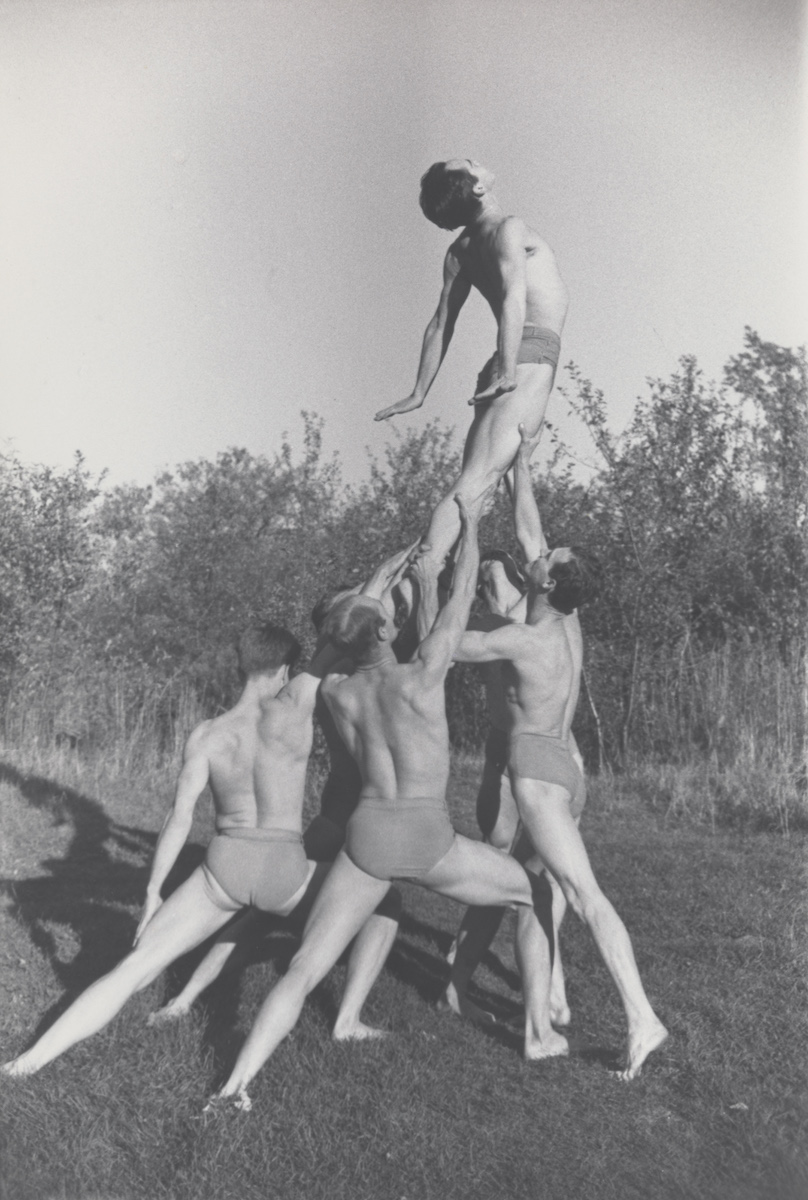

When Ted Shawn purchased the farm that would become Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, part of the reason was its location; it could serve as a retreat, so very different from his life in New York and Los Angeles. The Men Dancers, with whom Shawn collaborated for what he termed “seven magic years,” spent time crafting the land.

Ted Shawn quoted Scripture in titling his Pillow history How Beautiful Upon the Mountain, choreographer Joanna Haigood has called the grounds a “sanctuary,” and many other artists call the fields, woods, sky, and pond, an inspiration.