Racial Proscriptions in Ballet

Each artist is unique in his or her own way, but the uniqueness of black artists is sometimes compounded by their assignation as the “first” to breach the racial barriers in a particular field. For Janet Collins, the field was ballet. Arguably, none of the black artists who appeared at Jacob’s Pillow during the early days of the festival confronted and overcame the exclusionary practices of the ballet world to the extent that Collins did.

In concert dance during the 1930s and 1940s, classical ballet stood out as the dance form surrounded by the most proscriptive practices when it came to non-white dancers. I believe the racial sanctity of ballet was so closely guarded for a number of reasons. It was an art form developed out of an aristocratic European tradition, reflecting an imperious worldview in which lower-class inclusion was anathema. The historical contexts in which ballet developed—from the 16th century onward—included ideologies where race and class were conflated, and darker-skinned people were categorized as belonging to a lower class of performers and entertainers. On the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American stage, for example, it was understood that black artists were expected to perform in popular entertainment forms such as vaudeville and minstrel shows. Their participation in callings such as classical ballet was not to be tolerated. As an art form, ballet—like all theatrical dance—presents the dancer on stage where the audience can focus on all the visible manifestations of the human body, including the color of an individual’s skin. In addition, ballet’s aesthetic of consummate beauty—particularly in regard to the female dancer—has also been conflated with whiteness over the centuries.

Here, I feel the need to quote at length from a statement made in the 1960s that indicates how deeply racial proscriptions in ballet were ingrained in European and American culture. The statement is especially revealing because it was made by one of the leading dance critics of the time, John Martin of the New York Times:

. . . For its wholly European outlook, history and technical theory are alien to him [the black dancer] culturally, temperamentally and anatomically . . . In practice there is a racial constant, so to speak, in the proportions of the limbs and torso and the conformation of the feet, all of which affect body placement; in addition, the deliberately maintained erectness of the European dancer’s spine is in marked contrast to the fluidity of the Negro dancer’s, and the latter’s natural concentration of movement in the pelvic region is similarly at odds with European usage. When the Negro takes on the style of the European, he succeeds only in being affected, just as the European dancer who attempts to dance like the Negro seems only gauche.John Martin, John Martin’s Book of The Dance (New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1963), pp. 178-179.

Janet Collins recounted events in her life that tell us all we need to know about the racial proscriptions reflected in Martin’s words. After her family relocated from New Orleans to Los Angeles, when she was a young girl, Janet eventually became interested in dance. She studied with a teacher in her neighborhood for a while, then she began looking for better-known schools of ballet in the Los Angeles Area. Like so many aspiring black dancers, she was always turned away when the schools’ directors became aware of her race. Like so many aspiring black dancers during those years, she was always turned away when the schools’ directors became aware of her race. Their feeling was that the presence of a single black student in a class would threaten their business, because parents would withdraw their children. However, she did eventually find one teacher, Charlotte Tamon, who agreed to give her private lessons that provided her with thorough training.Yael Lewin, Night’s Dancer: The Life of Janet Collins (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011) pp. 16-17.

Collins later spoke of one memorable event that is related to one of the above-mentioned reasons for discrimination in ballet. When she was sixteen years old, her aunt suggested that she audition for an internationally-acclaimed ballet company that was performing in Los Angeles at the time, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. The company’s leading dancer and choreographer, Leonide Massine, conducted the audition. She described how she danced her heart out, after which the other dancers applauded enthusiastically. Then, she recounted the conversation she had with Massine after her audition:

He said in his Russian accent, “You are a very fine dancer.” I said, “I don’t think I am very strong yet for pointe, so I performed for you in ballet shoes.” “No, no,” he said. “You are strong. You will make a fine character dancer. I could train you.” I knew what he meant because character dancing was his forte in ballet. He stopped, thought very seriously—then, looking into my upturned waiting eyes, he stated in both a kindly and realistic manner, “In order to train you and take you into the company, I would have to put you onstage with the ballet corps first in performances—and I would have to paint you white.” He paused, “You wouldn’t want that, would you?” I looked directly at him and said “No.” We both understood. I arose, thanked him sincerely, and left.Ibid., pp. 20-21.

Collins went on to describe her emotional response after she left the theater for the trip back home. One can well imagine the crushing impact that such an experience had on a young person bent on dedicating herself to her chosen art form.

West Coast Musicals, Vaudeville, and the Dunham Company

Again—like so many young black artists during those years—Collins found her way, but at times it was very circuitous. She searched for different outlets through which to display her dance talents. A government-funded program, the Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre project, provided one such outlet. It was part of the Works Project Administration, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression to employee American citizens. It was remarkably progressive, in that it included expansive programs to employ artists.

The Negro Unit’s Los Angeles branch produced several shows, including Hall Johnson’s Run, Little Chillun. Doris Humphrey had arranged the dances in the New York version in 1933, but Janet Collins appeared in the west coast revival of the show in 1938. The next production she appeared in was the Swing Mikado which opened in Los Angeles in July of 1939.Ibid., p. 73

As biographer Yael Lewin details, the show-business aspect of Collins’ career also led her to tour with a vaudeville show organized by Eddie Anderson, the comedian who played the servant role on the Jack Benny Program. Her path through different theatrical genres finally led her to concert dance when a friend convinced her to go to a Katherine Dunham audition during the time her company was on hiatus on the west coast. Collins was accepted into the company, but she made it clear to Dunham that she would not stay with the group beyond a certain point, and the two agreed.Ibid., p. 75. She ended up leaving less than two years after she joined, and her departure with fellow company member Talley Beatty was an occasion that sparked fireworks of flaring tempers and volatile egos. Ostensibly, the two left together when Beatty complained about the inadequate housing conditions that the dancers had to put up with in Portland, Oregon. But beneath the surface, the conflict was fueled by the questioning attitude of the two younger artists versus the authoritarian disposition of a director whose decision-making was not to be questioned.

After leaving the Dunham Company, and briefly performing as a duo in nightclubs with Beatty, Collins began concentrating on plans to forward her career by presenting solo concerts in which she would perform her own choreography. To underwrite her project, she applied for and received a fellowship from the Rosenwald Fund, the same philanthropic organization that funded Katherine Dunham’s and later Pearl Primus’s research.

Collins remained in Los Angeles for almost three years working on her choreography and studying with the best teachers she could find. She was especially fond of Carmelita Maracci, who was a stunning performer in her own right and a skilled and highly-respected teacher.Carmelita Maracci also performed at Jacob’s Pillow in 1954. She shared a concert with the Lester Horton Dance Theatre, a company that included Collins’s cousin, Carmen de Lavallade, along with Alvin Ailey, James Truitte, Yvonne de Lavallade, and Joyce Trisler. Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival–Thirteenth Season–1954–July 22-24.

All of Collins’s efforts paid off when she presented her first solo concert on November 3, 1947 at the Los Palmas Theater in Los Angeles.Lewin, Night’s Dancer, p. 103. In spite of the fact that her concert was a popular and critical success, she soon realized that she would have to move to New York City in order to find the supportive environment she needed to forward her career.

A Warm Reception in New York

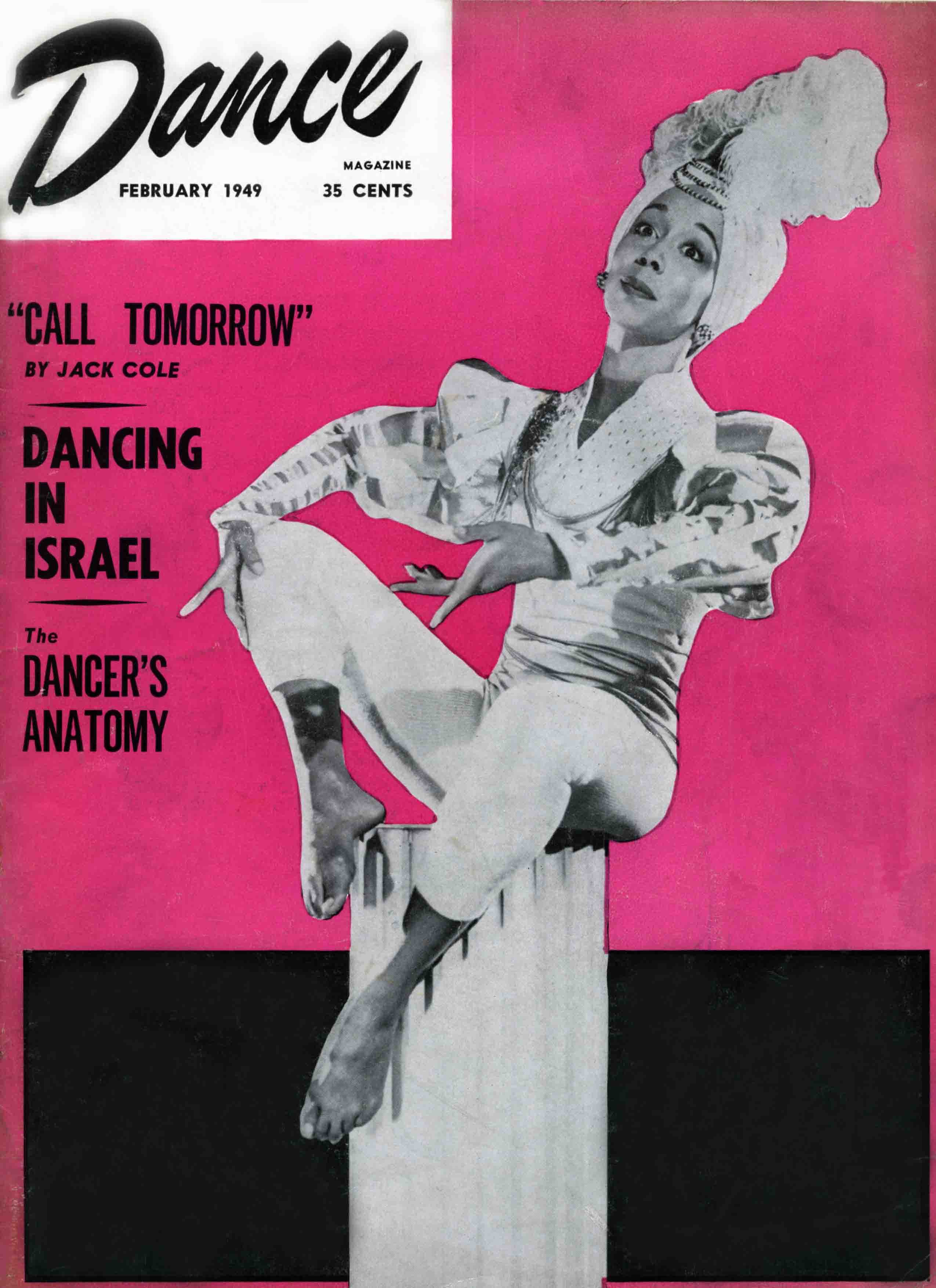

After relocating to the east coast and acclimating herself to the intensity of her new urban environment, Collins’s first important breakthrough occurred after she auditioned and was chosen to perform on a joint concert of emerging artists at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA on February 20, 1949. The reviews she received from dance critics such as John Martin of the New York Times and Walter Terry of the New York Herald Tribune were remarkably positive for an artist who was being seen in the city for the first time. Biographer Yael Lewin points out an interesting omission in the two critics’ reviews, “One thing in particular about both highly positive reviews distinguished the California transplant as an unusual find: the lack of acknowledgment of her fellow audition winners.”Ibid., p. 126. Lewin then goes on to discuss the reasons the omissions might have occurred, including the possibility that Collins’s performance was so overwhelming that the critics saw fit to only write about her. What was clear is that Collins’s long-standing commitment to push forward and take her artistic destiny into her own hands—as the choreographer and performer of her own work—was beginning to yield the results she desired. Her momentum in that direction continued when she returned to the YM-YWHA for a second time, as the sole performer in her own concert, on April 2, 1949.

The reviews of Janet Collins’s first solo concert in New York were glowing, and they referenced the depths of her gifts as an exceptional dance artist. After a brief caveat regarding the choreography itself, Doris Hering’s review in Dance Magazine detailed the multiple aspects of the artist’s gifts, “True Miss Collins made no choreographic innovations in this, her first New York concert, but the small messages her compositions did contain were conveyed by dancing—pure, unimpeded, uncluttered, unneurotic dancing in the joyous sense of the word—and with consistent good taste.”Doris Herring, “The Season in Review,” Dance Magazine, May 1949, p. 10. Hering continued, “Add to the picture a friendly personality that immediately establishes contact with the audience, an expressive face, impeccable grooming, and costumes that would do credit to the finest designer. They’re colorful, theatrical, and flattering. And Miss Collins designed them for herself!”Ibid.

Janet Collins at Jacob’s Pillow

No doubt, Collins’ stunning achievements during her brief time in New York brought her to the attention of Ted Shawn who was always looking for exciting new talent to present at his festival.

She appeared at Jacob’s Pillow on July 8 and 9, 1949, performing works that she had kept in her repertoire since her first solo concert in California. At her Pillow debut, she opened the concert with Blackamoor. A brief program note stated, “The court life of Louis XIV as seen through the eyes of a little Blackamoor.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival–Eighth Season–1949. One wonders if she intentionally chose her subject matter because of the irony it implied. In this solo, she embodied a black observer at the court of the French king who was responsible for laying the foundations of the very dance tradition she had chosen to pursue. Yael Lewin—as well as many dance critics who wrote about Collins—often commented on the dancer’s remarkable intelligence, so it is fair to speculate that she had researched all aspects of her choreographic choices. Moreover, that is exactly why she had spent almost three years in Los Angeles preparing her solos.

Lewin also points out another aspect of Collins’s artistic development that I have not mentioned before. She was a formally trained, exceptionally talented visual artist,One of the wonderful features of Night Journey is that it includes many beautiful reproductions of Collins’s artwork, including her colorful costume drawings. who was well-versed in art history and had probably seen paintings such as those depicting Louis XIV, surrounded by his courtiers, and often accompanied by a black child—usually an elaborately dressed boy—who was a servant. One wonders who those small footnotes to history were. Because of her inquisitive and probing mind, Collins very likely explored this type of source material in preparing Blackamoor. The resultant work was a humorous characterization of the blackamoor as a lighthearted and “spritely character, a little page boy peeping at the adults at the French court and trying not to be caught.”Lewin, Night’s Dancer, p. 104.

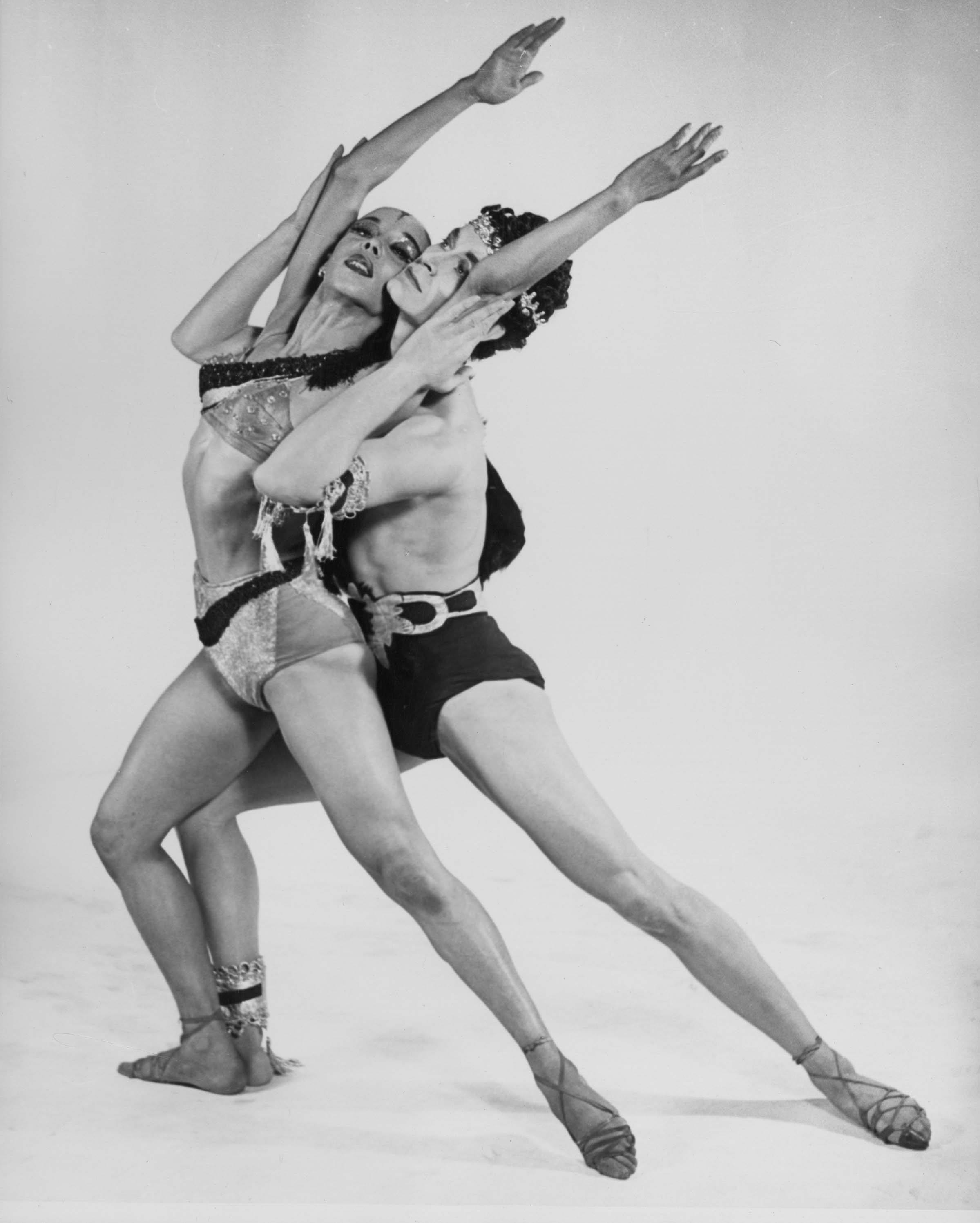

After the next section of the concert—a four-part Suite of Spanish Dances, performed by Pilar Gomez and Federico Rey—Collins danced Eine Kleine Nachtmusik to the music of Mozart. The work took full advantage of her polished ballet technique, even though it was obvious that Shawn’s programming featured her as the modern dancer of the concert. Many critics had remarked, as Doris Hering had, on Collins’s extremely accomplished ballet technique, and she had built a repertoire of works that deftly displayed it. But, at the same time, she was a pioneer in synthesizing the different dance genres she had studied, the ballet of Carmelita Maracci, Adolph Bolm and other teachers, the modern dance of Lester Horton and others, and the modern dance and African-diaspora dance she had learned through her Dunham experiences. In this approach, she was ahead of her time in the 1930s and 1940s, since the mixed-technique abilities of today’s dancers were much less common then. Again, it was the artist’s intelligence that enabled her to know when to emphasize one or the other aspect of her dance technique mélange, depending on what her choreography and subject matter needed.

The third offering for her Pillow debut concert emphasized the modern dance aspect of her training. After a performance of the Black Swan Pas de Deux from Swan Lake, danced by Jocelyn Vollmar and Igor Youskevitch, Collins returned to perform two negro spirituals, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen and Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel. Several months earlier, Doris Hering had seen the two dances in New York, and she had again written some of the most insightful reflections about Collins’s dancing. She commented, “Probably the most creative moments of the program occurred in the two spirituals, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen and Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel. Instead of merely illustrating them, as so many dancers are wont to do, she located the emotional source of the music and used that as a starting point. The movement radiated from a central axis on stage and kept returning to it. The whole body was constantly, ripplingly, in motion, and yet there was a still-souled calm about the whole conception.”Doris Hering, “The Season in Review,” Dance Magazine, May 1949, p. 10.

Broadway, the Metropolitan Opera, and Later Years

After her performances at Jacob’s Pillow, Collins continued the successes that had been compressed into her first two years in New York. On November 4, 1950, she opened in a Broadway musical, Out of This World. Though she had a minor role, it did include a long solo near the end of the first act.Ibid., pp. 158-159. And, her good fortune continued when she was hired by the Metropolitan Opera Ballet as their first African-American prima ballerina.

During her years at the Met, she received ample praise and glowing reviews for her appearances in operas such as Carmen, Aida, La Gioconda, and Samson et Dalila, but her tenure there was briefer than it might have been.

In her interview at Jacob’s Pillow, Yael Lewin comments on some of the reasons that Collins left the Metropolitan Opera in 1954, at a point when the management would have been happy for her to stay on. As the author explains, Collins was a deeply religious woman who, in spite of her love and long-standing commitment to dance, did not feel that a career as a performer was something that she wanted to continue beyond a certain point: “It wasn’t suiting her the way it used to. She did need more meaning. She was a deep person, a spiritual person. She needed more substance. She felt that the life of a performing artist was not giving her the satisfaction that she needed.”Maura Keefe, Interview with Yael Lewin, July 28, 2012, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Unlike many of the artists discussed in these essays, Collins did not return to the Pillow over the years; neither did she leave a tradition of having her works performed there by artists of later generations. However, an interesting footnote to her relationship with the festival can be found in Shawn’s yearly update that he mailed out concerning his activities during the previous year: “. . . lunch with Janet Collins talking about her major new work, Genesis which I HOPE we are going to have at the Pillow this summer; dinner with Janet and Eddie Villella at Sardi’s East . . . .”Ted Shawn, MY TWENTIETH ANNUAL NEWSLETTER IN LIEU OF THE CHRISTMAS GREETINGS I DID NOT SEND TO YOU AND TO THANK YOU FOR THE CHRISTMAS GREETINGS YOU SENT, February 22, 1964, Jacob’s Pillow Archives, p. 8. In addition, he sent her a preliminary contract as a follow-up to their meeting: “I am sending you this INFORMAL MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT in duplicate to confirm our correspondence and our conversation of yesterday regarding your engagement at Jacob’s Pillow this coming summer–1964. . . . . If the above agrees with your [understanding] of what we agreed upon verbally yesterday please sign one copy and return to me and keep one copy for your own records”Ted Shawn, Letter of Agreement, January 28, 1964, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

She had begun conceptualizing Genesis years earlier when she was still in California, with the objective of creating a lengthy solo based on the Creation story from the Bible. Over the years, she choreographed short sections, with the intention of building it piece by piece; but it was never realized as a full-blown work that could be presented at the Pillow. For Collins, choreography had always been a very slow process, and as her interest in her career began to wane during the 1960s, it may have become even more difficult for her to bring a work to fruition. An excerpt from Genesis that was eventually seen by the public was presented at “Collins’s last-known concert dance appearance, which took place at Marymount [Manhattan College] in a lecture-demonstration on February 23, 1965.”Lewin, Night Journey, p. 257.

Yael Lewin’s exceptional book about Janet Collins’s life and art includes discussions of her personal struggle with psychological problems such as her bouts of extreme depression. Consequently, I am even more amazed at the willpower she summoned up in face of the racial barriers that confronted her. Collins’s unrelenting effort to take her life and her art into her own hands was a remarkably courageous feat during those early decades, when stringent rules kept black artists from participating in the world of ballet. That she accomplished as much as she did, under those circumstances, and in a relatively short amount of time, is a testament to her intelligence, her fortitude, and her amazing talent.

PUBLISHED July 2017