A Pillow Tradition: Diversity in World Dance

I cannot think of more contentious issues in the arts than those surrounding the participation of black dancers in classical ballet performance. Over the decades, similar concerns have hounded the inclusion of black artists in opera, symphonic music, and various theatrical genres, but the racial issues that have attached themselves to ballet have a special stridency that begs to be addressed—and they have been repeatedly. Articles on the subject have included “Where Are All the Black Swans,” New York Times, May 6, 2007; “Does Classicism Have a Color?,” Dance Magazine, June 2005; and “In Our Words: Dancers, choreographers, and directors talk about race,” Dance Magazine, July 2010. All of the discussions ultimately point toward an extremely complex assemblage of aesthetic, political, and social concerns that have their roots in the racial ideologies of Western Europe.

Without going into great detail here, I will simply say that there is a historical continuum of European thought that privileges whiteness as the penultimate measure of human beauty, intelligence, and worth.The power to determine who can and cannot participate in an art form such as ballet is a matter that has profound sociopolitical implications. For centuries, individuals have been ranked on a scale where skin color—ranging from darker to lighter—determines the negative or positive characteristics that are thought to be pre-ordained in the racial order of things.A valuable reference that presents an overview of the issues involved here is “Race and Modernity” by Cornel West in The Cornel West Reader (New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books, 1999), pp. 55–87. His brilliant essay traces Western racial ideologies as they are rooted in the philosophical, scientific, and aesthetic thought of the European Enlightenment. I find that this white supremacist view of the world is clearly connected to racial proscriptions in art and culture. As in other instances of racial discrimination, the power to determine who can and cannot participate in an art form such as ballet is a matter that has profound sociopolitical implications.

During the 1920s and 1930s, when Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn were pursuing their dual enterprises of sustaining a school and a touring company, they were also affected by the sociopolitical dynamics I mention above. Consequently, I sense an inherent paradox within the creative lives of two of America’s leading concert dance pioneers. One the one hand, they were bound by the racial constraints of the time they lived in. (For example, I have written extensively on the career of an aspiring young African-American dancer, Edna Guy, who was closely associated with the Ruth St. Denis, but she could never aspire to actually perform with the company in the 1920s or 1930s.)See John O. Perpener III, African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Chicago and Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001), pp. 56 – 69. On the other hand, the very lifeblood of the Denishawn dance aesthetic was infused with elements drawn from the cultural veins of darker people—East Indian, Cambodian, Mexican, Native American, Cuban. There were African-American subtexts in Shawn’s suite of dances, Negro Spirituals. As author Susan Manning reminds us, “For Shawn, qualities associated with blackness—emotionalism, physicalized religiosity—become figures for what Western culture lacks and needs to become whole. Blackness becomes a projection of Shawn’s white imagination.”Susan Manning, Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Race in Motion (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), p. 27. Manning delineates how “danced spirituals” choreographed by Shawn and other European-American artists like Helen Tamiris reflected the artists’ vexed relationship with their source material. The author coined the interesting term metaphorical minstrelsy to describe the practice of white bodies performing black thematic material.

St. Denis and Shawn presented their iconic works during the early days of the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival; and they were joined there by another American artist, La Meri, who performed Hindu dances at the festival’s official opening in 1942. In 1951, Israeli-born Hadassah performed her country’s traditional dances, and she later returned with her own repertory of East Indian dances. Beginning with the festival’s first concerts, Ted Shawn implemented a programming format that was progressive for the time; and over the next thirty years of his life he maintained an artistically inclusive environment, presenting dancers from Sierra Leone, Haiti, China, Spain, and a host of other countries. Artists of many nationalities and ethnicities brought their distinctive dance expressions to the Pillow, performing on joint programs and receiving equal billing with European and European-American artists. No doubt, these performances helped ameliorate historically entrenched hierarchies in the arts.

A Pillow Tradition: Diversity in Ballet?

Another strong suit of the Pillow’s programming has always been the presentation of American and international ballet artists. In 1941—the year before Shawn’s festival officially opened—a benefactor leased the Pillow’s facilities for British ballet artists Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin, and they presented the “International Dance Festival.” Their program included performances by Agnes de Mille, Lucia Chase, Antony Tudor, and Nora Kaye, as well as appearances by Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, and the tap dancer Paul Draper.Norton Owen, A Certain Place: The Jacob’s Pillow Story (Becket, MA: Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 2002), pp. 11 – 12.

Further examination of the Pillow Archives indicates a modicum of ethnic diversity among the ballet artists who have performed at the festival. Native American ballerina Maria Tallchief first visited the Pillow in 1951. She performed on a program she shared with La Meri and Di Falco. As Director of Preservation Norton Owen notes, Tallchief appeared in dozens of performances at the Pillow over the years; she maintained a close friendship with Ted Shawn, and he named one of the student cabins after her in 1965.Norton Owen, Maria Tallchief—Pillow Remembers, 2013, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. In 1951, a brief film of Tallchief and Michael Maule was recorded at the Pillow, when they performed an excerpt from George Balanchine’s The Firebird.

Decades later, the inclusion of non-whites in the world of classical ballet was reflected in the performances of the Hong Kong Ballet at the Pillow during the 2012 and 2014 seasons. Over the years, audiences in the Berkshires were able to glimpse the possibilities of diversity in ballet performance, and African-American artists were a part of those diverse offerings, in spite of the racial proscriptions that impacted them during those same decades.

In another essay for this series, I discussed Janet Collins’s breakthrough as the prima ballerina of the Metropolitan Opera Ballet and her visit to the Pillow in 1949. During the 1930s, when Collins was an aspiring young dancer, there were other attempts to create opportunities for African-American dancers in classical ballet. Those projects were undertaken by European-Americans and African-Americans. Eugene Von Grona, for example, established an all-black company, the First American Negro Ballet, after he moved from Germany to the U.S. in the mid-1920s. His group presented its first concert at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem in 1937. Ten years later on the west coast, a similar group—the First Negro Classic Ballet—presented its first concert in Los Angeles, under the direction of Joseph Rickard, a former student of Irina and Bronislava Nijinska. The following decade, Ward Flemyng organized the New York Negro Ballet, a company that distinguished itself by undertaking a tour of Great Britain in 1957.For detailed information on this company see Dawn Lille Horwitz’s “The New York Negro Ballet Company in Great Britain” in Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Thomas F. DeFrantz, ed. (Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002), pp. 317 – 339.

Why have there been such persistent efforts to create spaces for African American dancers in the world of ballet? Classical ballet has held a special place in Western aesthetics as a bastion of white, European-American exclusivity; and, for some individuals, breaching those historical walls of exclusion has been as important as the advancement of black people in social, political, or economic arenas. To address the issues imbedded in this question, a number of dance scholars have turned to theoretical approaches to examine how dance performance can be used to include members of ostracized—and less powerful—groups in areas of society from which they have been excluded by powerful, dominant groups. For example, dance scholar Dana Mills—in Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries—theorizes the unique ability of dance to communicate in a way that creates a state equilibrium between the dancer and the spectator. She speaks of dance as a non-verbal, embodied language that is capable of establishing a relationship in which the one who dances and the one who observes share a common embodied space in a remarkable way. The dance phenomenon establishes an equality that may not exist between the two bodies in other facets of their lives, most notably those areas that are controlled by verbal communication.Dana Mills, Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2017), pp. 24 – 26. Mills stresses the ability of dance to ameliorate matters such as gender, race, and class in a way that empowers individuals who have been disenfranchised. Their dancing provides them with an agency that resonates with political and social power that is capable of changing the status quo.

When we watch a dancing human body on the theatrical stage there is an intense focus on every aspect of the dancer’s physical presence—their skin color, their bodily configuration, their gendered appearance; and stage technology is meant to heighten our visual perceptions of the performers. All of those factors are further compounded by the preconceptions that we bring with us to our viewing experiences, including those that have to do with racial issues. In the same vein, the history of black artists and their attempts to gain entry into the world of ballet is replete with instances where dancers have been told that their skin color would ruin the symmetry of the corps de ballet, or their presence in certain narrative ballets would seem ludicrous. And yet, they—and their white supporters—have persisted.Artists have always sensed the power of dance to effect change… They may not have articulated the relationships between art and sociopolitical dynamics with the scholarly acumen that Dana Mills displays, but artists have always sensed the power of dance to effect change, and they know that the study and the performance of classical ballet can make valuable contributions to people’s lives. For example, a 1997 statement of the Dance Theatre of Harlem’s mission captures this understanding: “Building upon its original mission—at once social, educational and artistic—to provide children and adults everywhere with the opportunity to learn and experience the discipline of dance and the joy of the performing arts, Dance Theatre of Harlem continues to bridge the gaps of cultural and economic disparity and stereotypes.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival 1997—Dance Theatre of Harlem—Ted Shawn Theatre—August 5-9, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

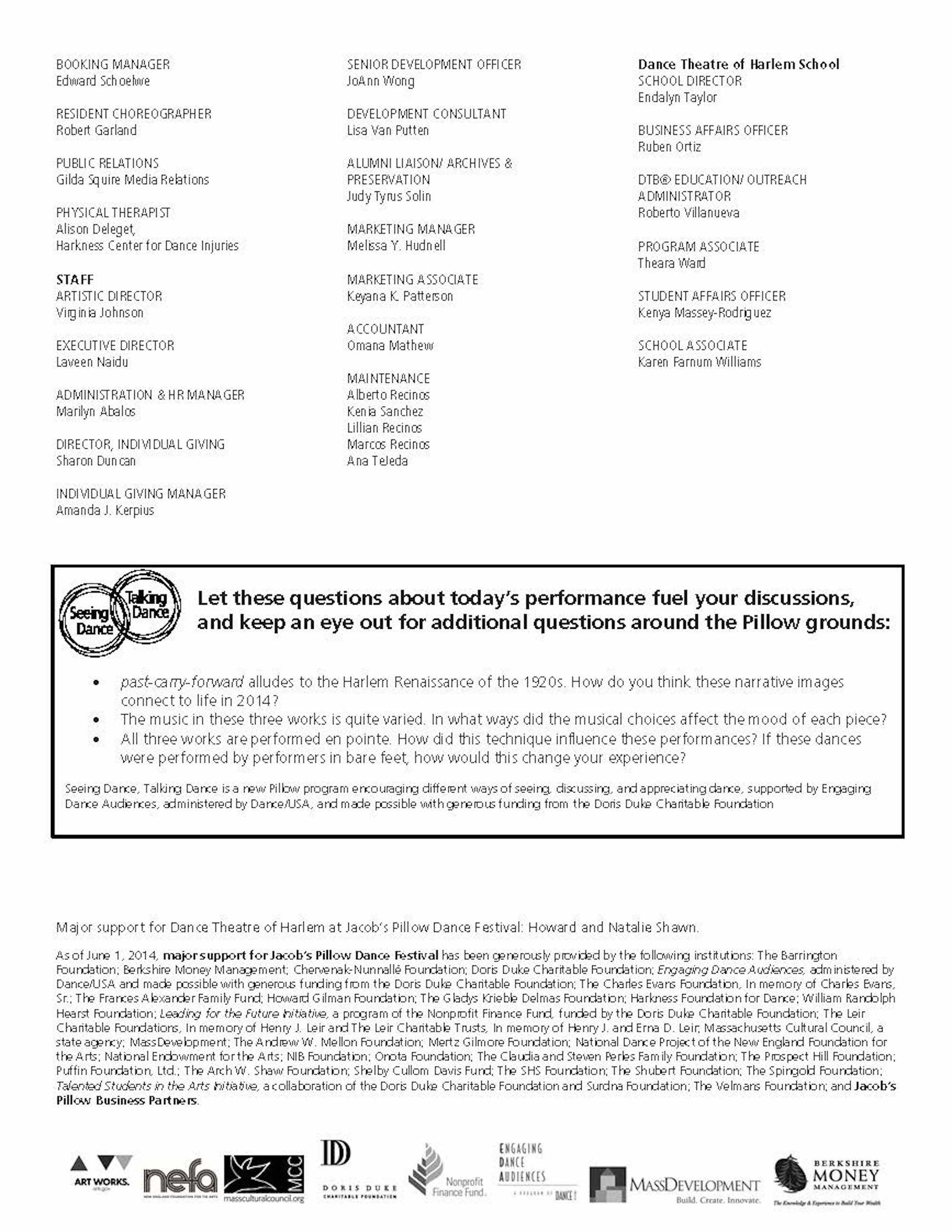

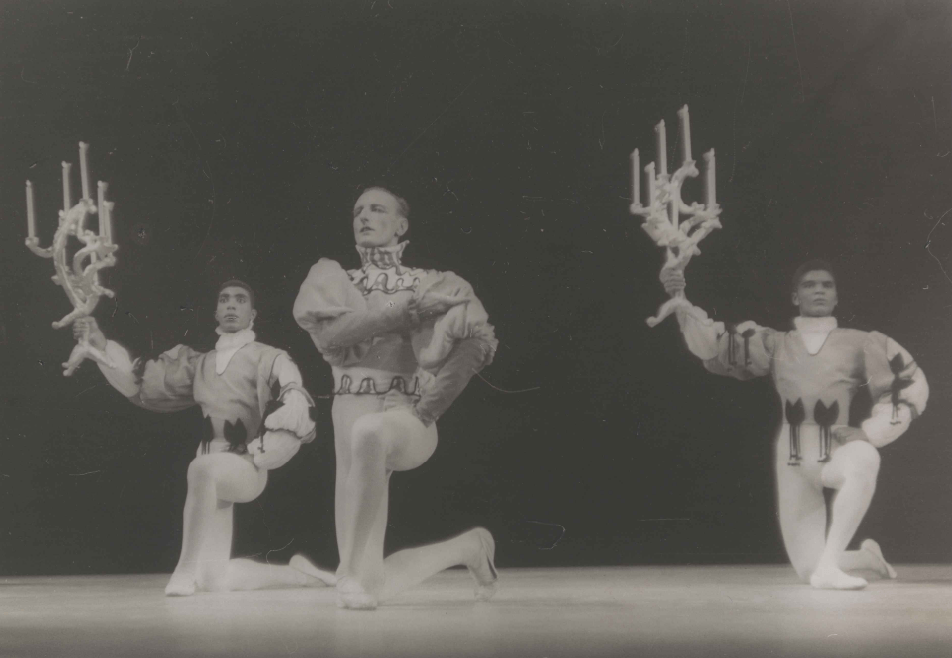

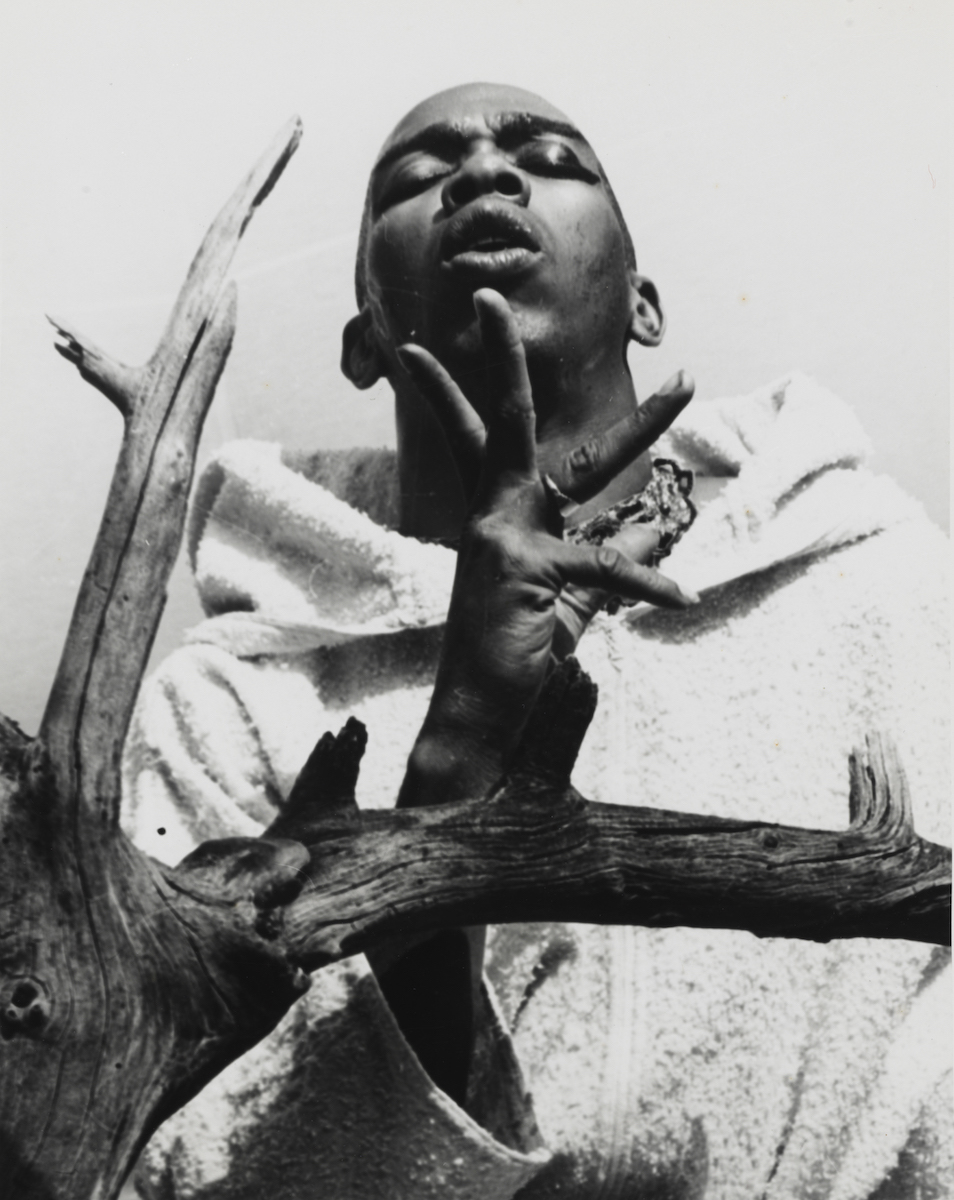

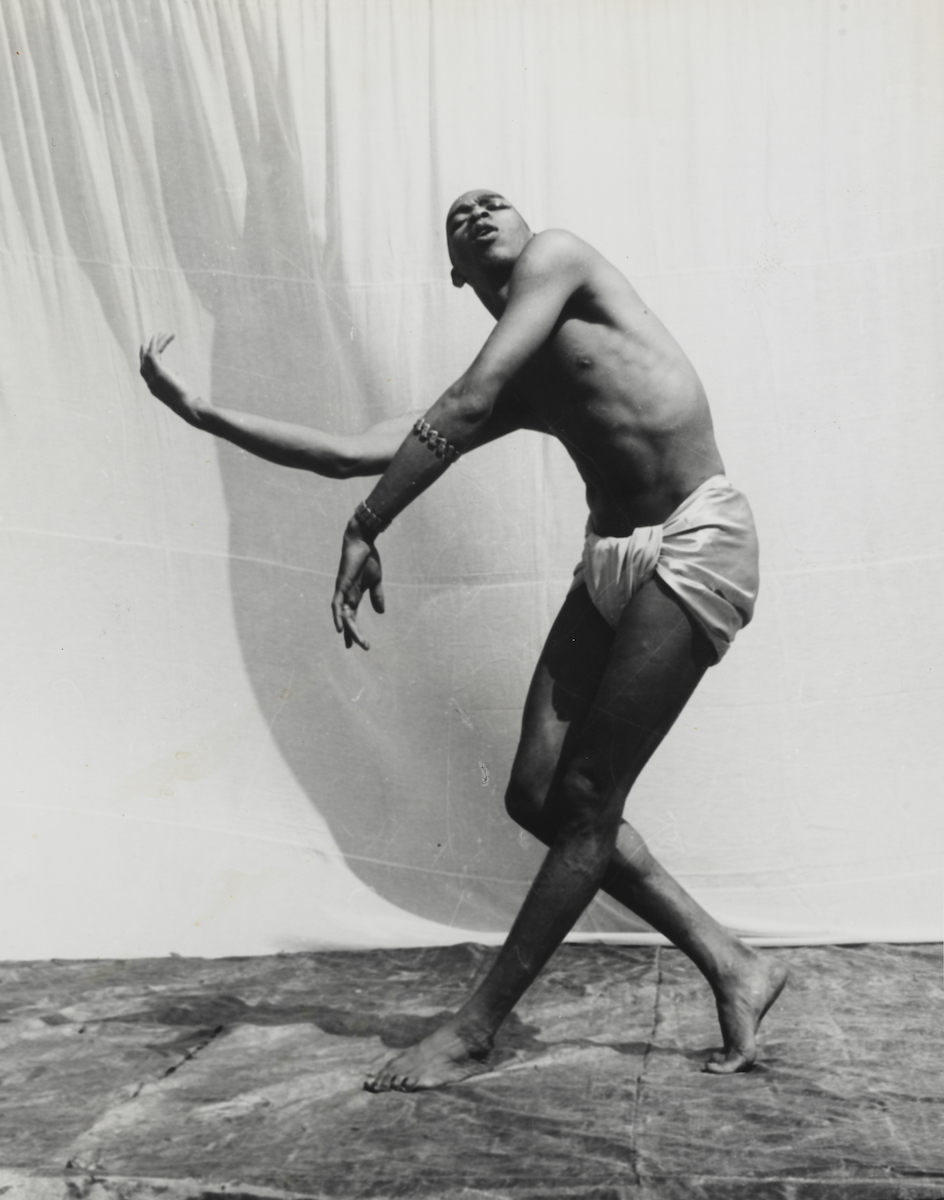

The racial/aesthetic dynamics I am discussing were certainly part of the scenario in 1954, when the Negro Dance Theatre visited Becket, Massachusetts. The company was directed by Aubrey Hitchins, whose artistic background included studying with major Russian ballet teachers and partnering Anna Pavlova on her international tours. He had performed as “First Dancer” of the Monte Carlo Opera House and of the Municipal Theater in Caen, France, where he also served as Ballet Master.Short Biography of Aubrey Hitchins, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. In addition, Hitchins had served as Ballet Master at the Metropolitan Opera House, established his own school in New York in 1947, and previously taught classes at the Pillow. In 1953, he invited several black dancers to work with him at his New York studio, because he “[a]rdently believ[ed] in the special dance talents of the Negro race,” and he realized that there had never been an attempt to form an all-black, all-male ballet company.Negro Dance Theatre—Aubrey Hitchins, Artistic Director, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. On their first visit to the Pillow, Hitchins’s company performed Italian Concerto, which was choreographed to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. The work for ten dancers was the company’s sole offering on a program they shared with Kurt and Grace Graff, Inge Sand, and Vladimir Dokoudovsky. Archival photographs capture Hitchins performing with the company. I could not find an explanation for his own appearance as part of an ensemble that was so strategically intended to showcase black artists. Was he filling in for someone at the last minute?

A few days later, Hitchins sent Shawn a letter of thanks for being such an attentive host:

You were so kind and thoughtful of every detail throughout our stay at the Pillow but there are two acts which I would like to mention first: the fact that you were standing outside the Theatre awaiting our arrival was very moving to me and when you made a special trip to bring ice because you realized it might be needed. I am sure you know that it is rare to encounter such human kindness in the theatre.Letter from Aubrey Hitchins to Ted Shawn, August 30, 1954, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

When the Negro Dance Theatre returned to the festival the following year, their roster of dancers included Charles Moore, who later performed at the Pillow with Geoffrey Holder’s company in 1958 and Talley Beatty’s company in 1960. Moore returned with his own company in 1976 and 1978.

The Negro Dance Theatre performed their expanded repertory on August 26 and 27, 1955. There was a new work by Dania Krupska, Outlook for Three, that consisted of vignettes depicting three men who had just been released from prison. And Hitchins premiered a new work, Ode, that alternated with a reprise of his Italian Concerto. The third new work on for the company was Tony Charmoli’s Gotham Suite. Other pieces on the program included two works by Xenia Zarina based on Balinese and Cambodian dance motifs; and Ruth St. Denis performing Freedom, White Nautch, and Cadman Nautch.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Fourteenth Season—1955, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Shawn’s kaleidoscope of dance continued to bring African-Americans to the Pillow, including artists who endeavored to be taken seriously in the world of classical ballet. Among those, Arthur Mitchell stands out as a visionary whose work served as a remarkable catalyst for black artists to enter that rarefied world.

Arthur Mitchell: A Dream NOT Deferred

Arthur Mitchell, along with his mentor Karel Shook, founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969. The company would go on to become the first predominately-black ballet company to thrive for an extended period of time—thirty-five years, in its original iteration—and it would garner a level of national and international acclaim that was extraordinary for such an organization. Far out-distancing earlier attempts to present African-American artists as accomplished classical ballet dancers, Mitchell drew upon the skills and aesthetic sensibilities he had gained from his own artistic training and performing experiences to initiate his ambitious project. He used the clarity of his expansive vision, and the force of his charismatic personality to launch an undertaking that would have lasting effects on the world of ballet.

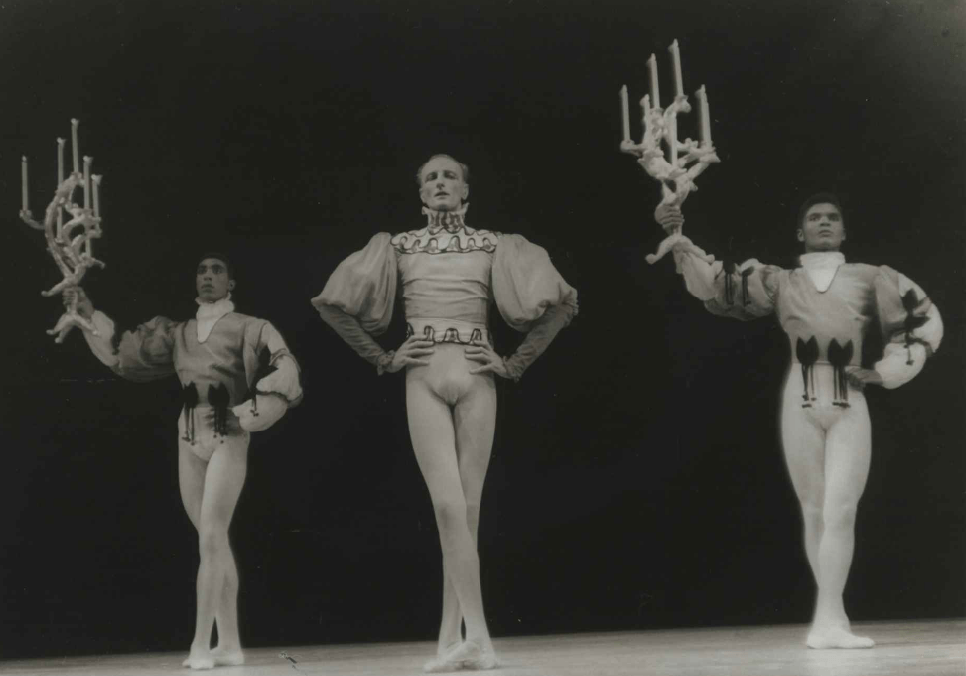

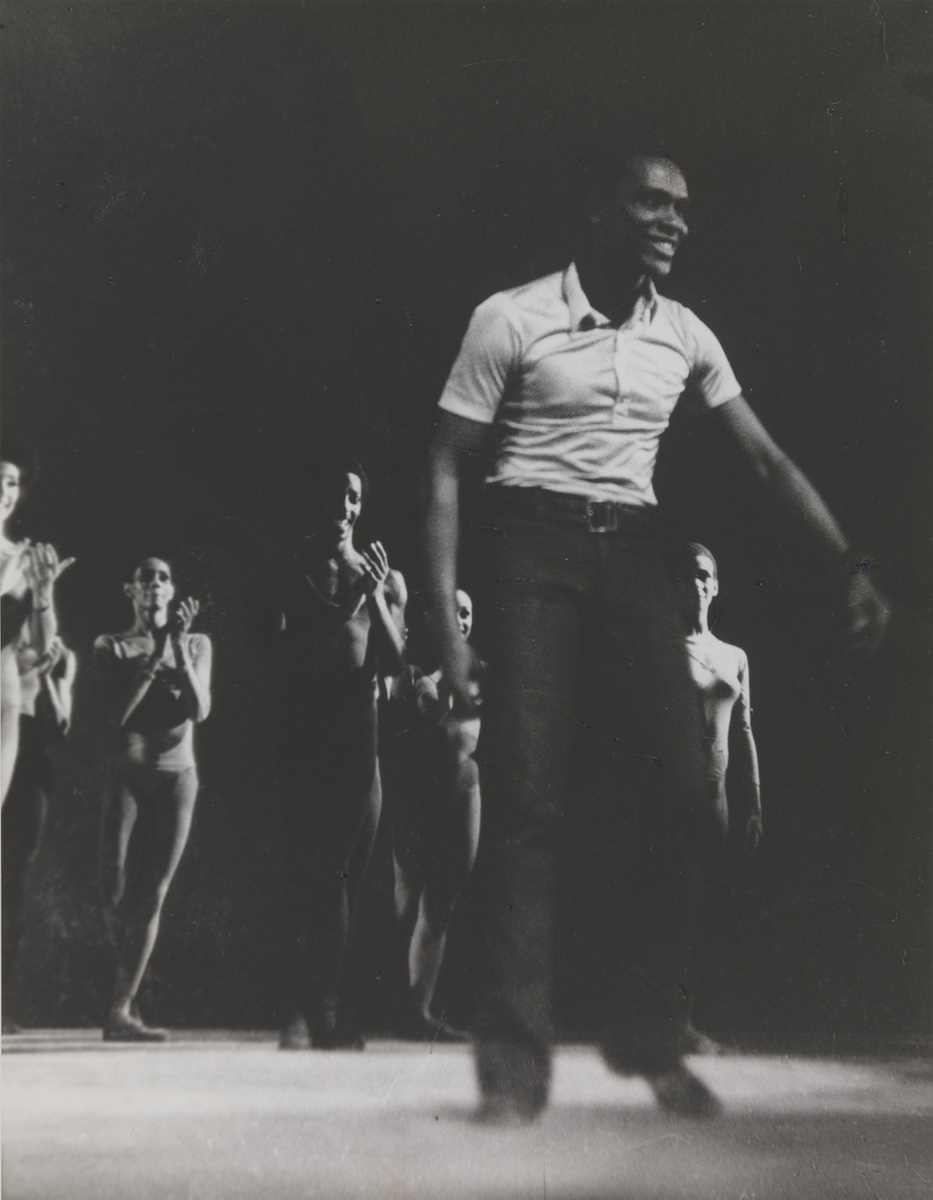

Mitchell was an individual who was accustomed to breaking barriers and accomplishing firsts. In 1955, he became the first African-American principal dancer in George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet, and he went on to receive praise for his signature performances in a number of ballets—partnering Tanaquil Le Clercq in Western Symphony, as Puck in A Midsummer’s Night Dream, and partnering Diana Adams in the central pas de deux in Agon. In 1968, he broadened his horizons once more by accepting an offer from the USIA to establish a ballet company in Brazil. For a while, he shuttled back and forth between Brazil and the U.S. to fulfill that mission; but when he was jolted by the news of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he knew that he had to change the direction of his life’s work. He returned home to Harlem, where he set about opening his first school; it soon offered ballet classes for hundreds of neighborhood children and teen-agers. With methodical precision, Mitchell soon began presenting his more accomplished dancers in lecture-demonstrations that presented the technical exercises and movement vocabulary of the danse d’école as a primer for community members who were seeing ballet for the first time. His audiences were often composed of school children, and he drew upon his charisma and charm to serve as an ambassador for the art of ballet. When Mitchell visited Jacob’s Pillow in 1997, he reflected on some of the early experiences that shaped his life as a performer, teacher, choreographer, and founder of a school and company.

The First Visits of Dance Theatre of Harlem to the Pillow

Arthur Mitchell was associated with the Pillow years before his company’s first appearance there. As Norton Owen reminds us, Mitchell performed with Donald McKayle’s company at the age of nineteen in 1953.Norton Owen, Arthur Mitchell—Pillow Remembers, 2018. Jacob’s Pillow Archives. He danced in what would become two of the choreographer’s signature works—Games and Nocturne. He also performed with John Butler in 1955.

The Dance Theatre of Harlem’s official debut performance is most often spoken of as having taken place at the Guggenheim Museum on January 8, 1971. The New York City location certainly gave that occasion an imprimatur of auspiciousness. However, the company’s first performances for a paying, concert-going audience actually occurred several months earlier, August 18 to 22, 1970, at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. The company of nine dancers performed a program of four dances choreographed by Arthur Mitchell: Holberg Suite, Biosfera, Ode to Otis, and Rhythmetron. There were no descriptive notes on the printed program and no archival footage of the performance exists; but, when DTH visited the Pillow in June 2010, Virginia Johnson—a founding member of the company who now serves as its artistic director—recalled a few details about the performances. She remembered that Ode to Otis had opened with Otis Redding’s Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay. (The program, however, only attributed the music to African-American composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson.) Johnson noted that Rhythmetron was originally created for the company Mitchell had established in Brazil, and it was a ritual piece danced to a percussive score by Brazilian composer Marlos Nobre. During her PillowTalk, Johnson also shared her memories of her early years of training in Washington, DC and her first encounters with Arthur Mitchell.Virginia Johnson, Virginia Johnson Returns, PillowTalk, June 21, 2010, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Following their initial visit to the Pillow, Dance Theatre of Harlem traveled to Europe for the first time to perform at the Spoleto Festival in 1971. Members of the company appeared at the Pillow again in 1973 in two interesting programs. First, Paul Russell—a dancer who had begun distinguishing himself as an outstanding member of the company—appeared on a concert simply titled Pas de Deux Program from July 31 to August 4, a mixed-bill which included both modern dance and ballet. Bruce Becker and Jane Kosminsky performed Norman Walker’s Meditations of Orpheus; Russell and Roni Mahler followed with the pas de deux from Paquita; Jacqueline Rayet and Jean-Pierre Franchetti danced Maurice Béjart’s Webern Opus 5; Melissa Hayden and Peter Martins performed Michael Uthoff’s Aves Mirabiles; Bruce Becker returned to the stage in Helen Tamiris’s six-part Negro Spirituals; and the concert closed with Jacqueline Rayet and Jean-Pierre Franchetti dancing Victor Gsovsky’s Pas de Deux d’Auber.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—July 31-August, 4, 1973—Pas de Deux Program. Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

A few days later, on August 7-11, DTH company members shared a program with Carmen de Lavallade who performed Ruth St. Denis’s The Incense and The Yogi, Geoffrey Holder’s Songs of the Auvergne, and The Vagabond (based on the writings of Colette and directed by Sondra Lee). DTH company members performed John Taras’s Design for Strings, Mitchell’s pas de trois from Holberg Suite, and a pas de trois and pas de deux from George Balanchine’s Agon. (Over the years, attesting to his ongoing support for Mitchell’s vision, Balanchine contributed several of his masterworks to the company’s repertory.) De Lavallade closed the program with Holder’s The Creation.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—August 7-11, 1973—Carmen de Lavallade – Members of the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

The Company’s Halcyon Days

Dance Theatre of Harlem’s next performance at Jacob’s Pillow took place on August 5-9, 1997. During the twenty-seven years since their previous visit, the company had established a major presence on the international dance stages of the world. As stated in the program:

Among the highlights of DTH’s early international acclaim are command performances for European royalty and historic engagements at London’s Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. In 1988, Dance Theatre of Harlem was the first American ballet company to perform in the Soviet Union as part of the US/USSR Cultural Exchange Initiative. This landmark five-week tour sold out in Moscow, Tbilisi and Leningrad, where the company received a standing ovation at the Kirov Theatre. In 1990, Dance Theatre of Harlem made its first appearance on the African continent, performing at the National Cultural Center in Cairo, Egypt. In 1992, Dance Theatre of Harlem returned to the continent for an unprecedented tour in South Africa. Performing to critical praise and integrated sold out houses, DTH succeeded in providing Dancing Through Barriers activities to the townships surrounding Johannesburg and within the city over a six week period. Most recently the company has performed internationally at the Biennale Festival Lyon (1994), Lille, France (1995) and Istanbul, Turkey (1995). During the 1995/1996 season, the company also completed two sold out tours of Brazil within a nine month period.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival 1997—Dance Theatre of Harlem—Ted Shawn Theatre—August 5-9, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

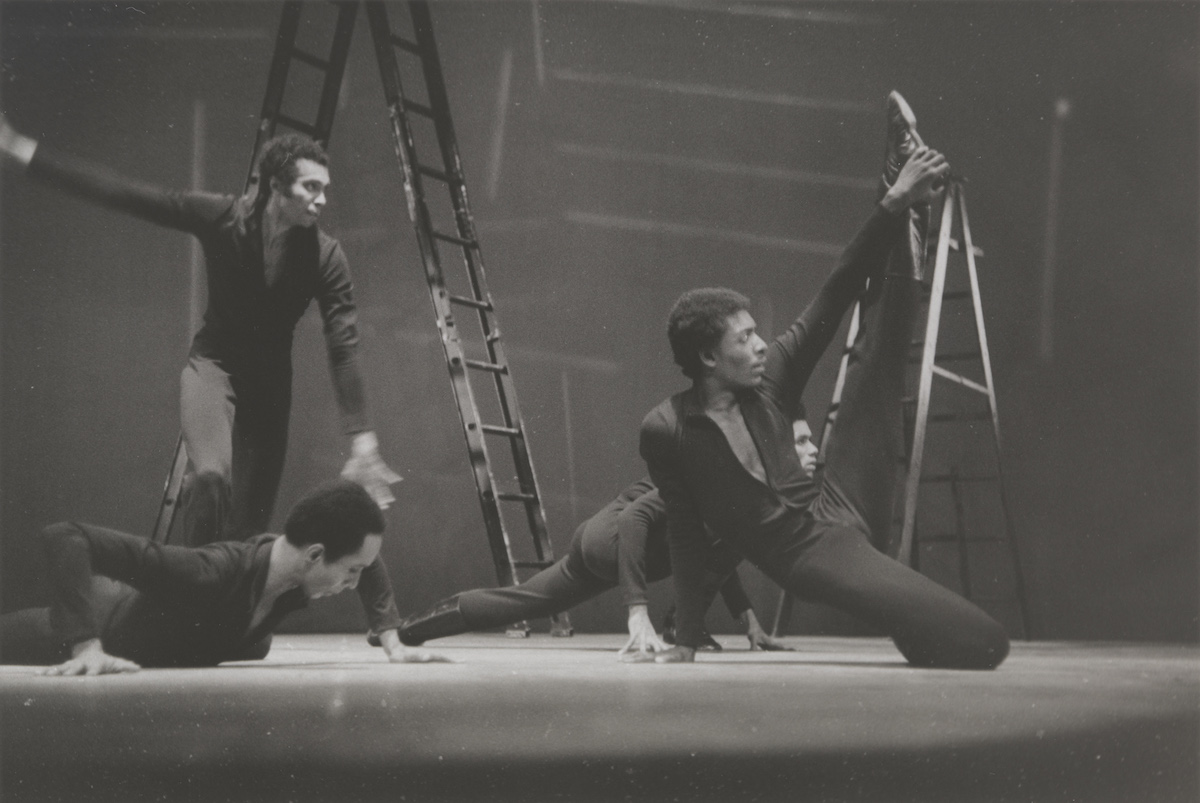

Mitchell presented three works that showcased the diverse skills of his thirty-six dancers. The program opened with Adrian (Angel on Earth) choreographed by John Alleyne. Born in Barbados, Alleyne moved with his family to Toronto when he was a young child, and eventually began a career in dance that led him to become a member of the Stuttgart Ballet and later the National Ballet of Canada. Adrian was an innovative work that complemented Mitchell’s objective of expanding his company’s expressive movement vocabulary that was grounded in classical ballet. The program noted that the work was part of a trilogy describing the epic journey of a hero who finally experiences “a physical and spiritual rejuvenation through hope and inspiration.”Ibid. Performed to Timothy Sullivan’s lush score for two pianos, the work was replete with duets, trios, and other groupings that delineated the deeply-felt emotions and complex dynamics of human relationships. The work was also noteworthy for its numerous sections that featured male/male partnering.

The second work on the program was choreographed by a young South African choreographer, Vincent Sekwati Mantsoe. Mitchell met Mantsoe during his trip to South Africa and his interaction with Sylvia Glasser, director of Moving Into Dance Company (MID) in Johannesburg. Glasser had established her racially integrated school and company in 1978 in defiance of the apartheid policies that dominated race relations in South Africa. Mantsoe, originally a scholarship student at MID, had quickly distinguished himself as a solo performer, choreographer, and teacher; and he eventually served as the company’s co-director.

Mitchell later remembered how he had refused initial requests for DTH to visit South Africa, because he felt that he would not be able to control his reactions to the apartheid system in that country; but Nelson Mandela prevailed upon him, saying, “…Arthur, Dance Theatre, at this particular time, is the only company that can come and show our society what can happen when any child is given an opportunity.”Arthur Mitchell, Blacks in Ballet and the Rise of Dance Theatre of Harlem—PillowTalk—August 8, 1997. Mitchell agreed to go with certain stipulations such as assurance that stage crews and film crews would be racially integrated. Mantsoe was in one of the classes he taught, and when Mitchell ran into Sylvia Glasser in New York City some years later, he inquired about the possibility of reconnecting with the young artist and inviting him to choreograph a work for DTH. Mantsoe had never worked with a major company or with ballet dancers, but Mitchell, as usual, followed his intuition.Ibid. The work, Ssanka, premiered in April, 1997 at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in a series featuring the art of Africa and its diaspora, African Odyssey.

Mantsoe’s choreography drew on the aesthetic of “Afrofusion” that Glasser had been developing at her school in Johannesburg. He incorporated African-derived dance motifs in which the dancers often moved with deeply-bent knees and concave torsos, along with modern dance and balletic movement. Several years later, in 2004, artist/scholar Thea Barnes spoke of Mantsoe’s unique aesthetic in an article in ballet—dance Magazine:

He draws from culturally specific dance aesthetics found in Europe, Asian [sic] and Africa. Movement experiences in these contexts are culturally specific, temporal and special events. For Mantsoe this confluence of cultural specificity, his particular encounter with alternative culturally specific dance aesthetics coupled with reflection of his childhood experiences in dance with his family in Soweto, encourages, indeed excites his choreographic inspirations.Hybrid, amalgam, and synthesis are some of the words that describe the types of black choreographers brought to the Pillow over the decades. It is this overlap of worlds, the present day to day encounters impacting recollections and explorations with past and present dance-making practices that makes Mantsoe’s aesthetic an intertextual event.Thea Nerissa Barnes, Interview with Vincent Sekwati Koko Mantsoe, www.ballet-dance.com/200402/articles/interviewvincentmantsoesekwati20040100.html

Hybrid, amalgam, and synthesis are some of the words that describe the types of black choreographers brought to the Pillow over the decades.

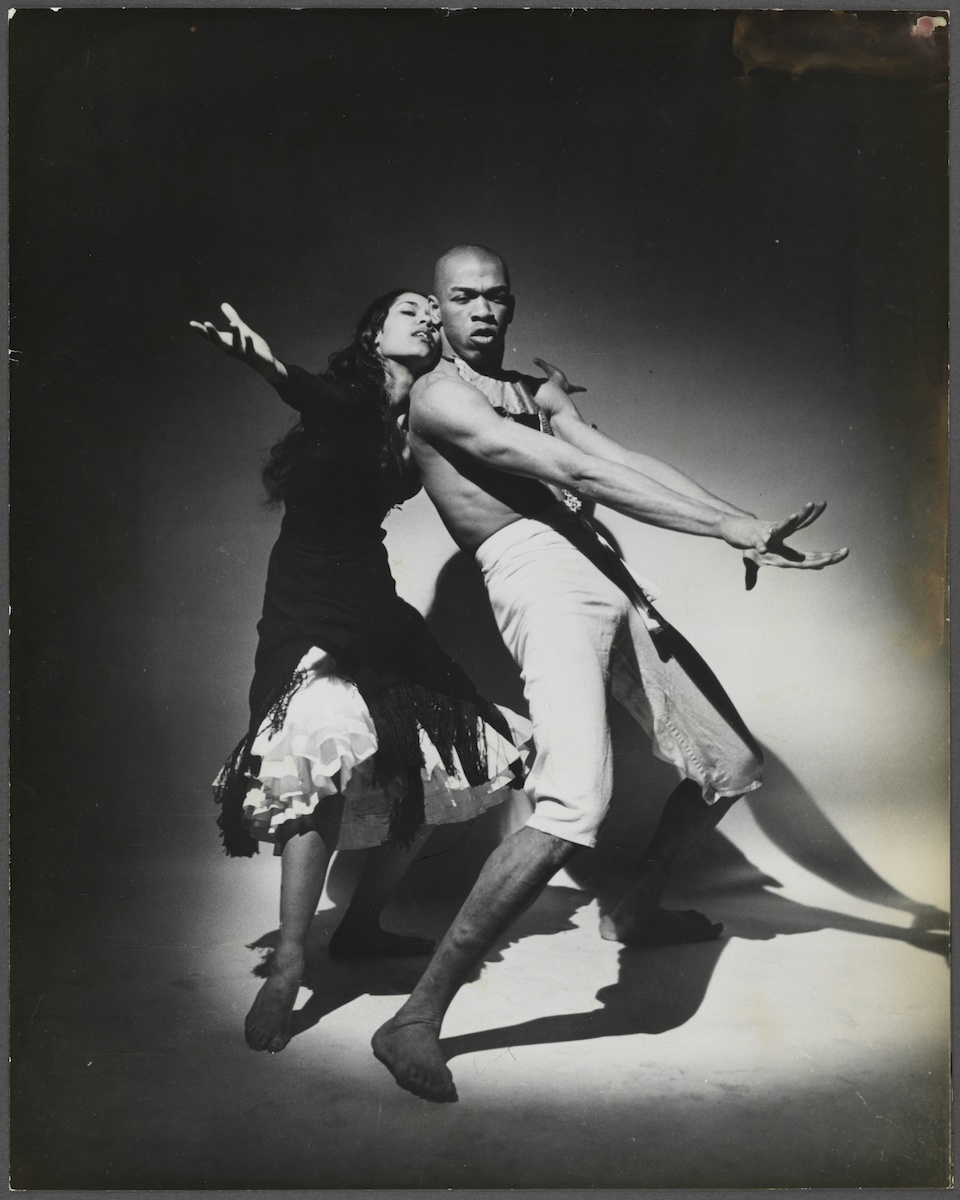

The final dance on the 1997 program was choreographed by another artist whose work drew from several different cultures. Dougla was Geoffrey Holder’s colorful and panoramic masterwork that depicted the unique mix of African and East Indian culture found in his home island of Trinidad. Holder first appeared at the Pillow in 1954 with his own company; and he and his wife, Carmen de Lavallade, performed at the festival many times during the 1950s and 1960s.

During those decades, Holder presented several iterations of a work that was titled Doogla. (Somewhere along the way the spelling was changed to Dougla.) In 1954, a cast of four dancers performed the work, but for the 1997 DTH performance at the Pillow the cast consisted of thirty-two dancers. Dougla conjured the story of a mixed-race wedding that unfolded in a mesmerizing pageant of beautiful human beings in exquisite costumes designed by the multi-talented choreographer.

The Years of Hiatus, Reorganization, and Rebirth

DTH disbanded in 2004, because the organization had accumulated an enormous amount of debt. By 2008, however, a smaller performance group—the Dance Theatre of Harlem Ensemble—had been established, and it visited the Pillow for an Inside/Out performance on July 18. Resident Choreographer Robert Garland opened the program with a brief history of the company. He then explained that the dancers who would perform were formerly members of an ensemble that was part of Dancing Through Barriers. In that capacity, they had been involved primarily in DTH’s educational and community outreach initiatives. However, the 2008 Pillow program was the premier performance of the Dance Theatre of Harlem Ensemble, a group that would soon be embarking on concert tours in addition to the educational activities that Arthur Mitchell had championed from the earliest days of his company.DVD recording #3606, Dance Theatre of Harlem, Inside/Out—2008/07/18, Jacob’s Pillow Archive. The program consisted of Mitchell’s Balm in Gilead and The Greatest, Lowell Smith’s Fragments, and excerpts from Robert Garland’s Joplin Dances and Return. On the same program, the fourteen dancers also performed in two lecture-demonstration segments, Pointe Work Discussion & Demonstration, and Partnering Discussion and Demonstration.Ibid.

The Dance Theatre of Harlem Ensemble was part of the re-organization efforts of Artistic Director Virginia Johnson and Executive Director Laveen Naidu, who had embarked on a plan to put the company back on solid footing. The group appeared at the Pillow again in 2010, and they exhibited a refreshed version of Mitchell’s artistic vision. The seventeen members danced in a program consisting of an excerpt from one of Mitchell’s early works, Fete Noire (1971), set to Dmitri Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2; Peter Pucci’s duet, Episode (2009); and Robert Garland’s New Bach (2001). A fourth work, South African Suite (1992), was co-choreographed by Augustus van Heerden, Laveen Naidu, and Arthur Mitchell.

The program noted:

Through music and movement, the many facets of South Africa are brought out of the earth, revealing the commonality of humankind. This is a place where the spirit of the people endures forever despite their lamentations and, like the animals, can be both playful and fiercely majestic. In 1992, Dance Theatre of Harlem made history as the first American company to perform in South Africa after the thirty-year ban was lifted. That unprecedented six-week tour received critical praise and played to integrated sold-out houses.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Presents Dance Theatre of Harlem Ensemble—Doris Duke Theatre—June 23-27, 2010, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Van Heerden and Naidu were former members of the company who hailed from South Africa, and their joint collaboration with Mitchell produced yet another synthesis of distinct dance idioms.

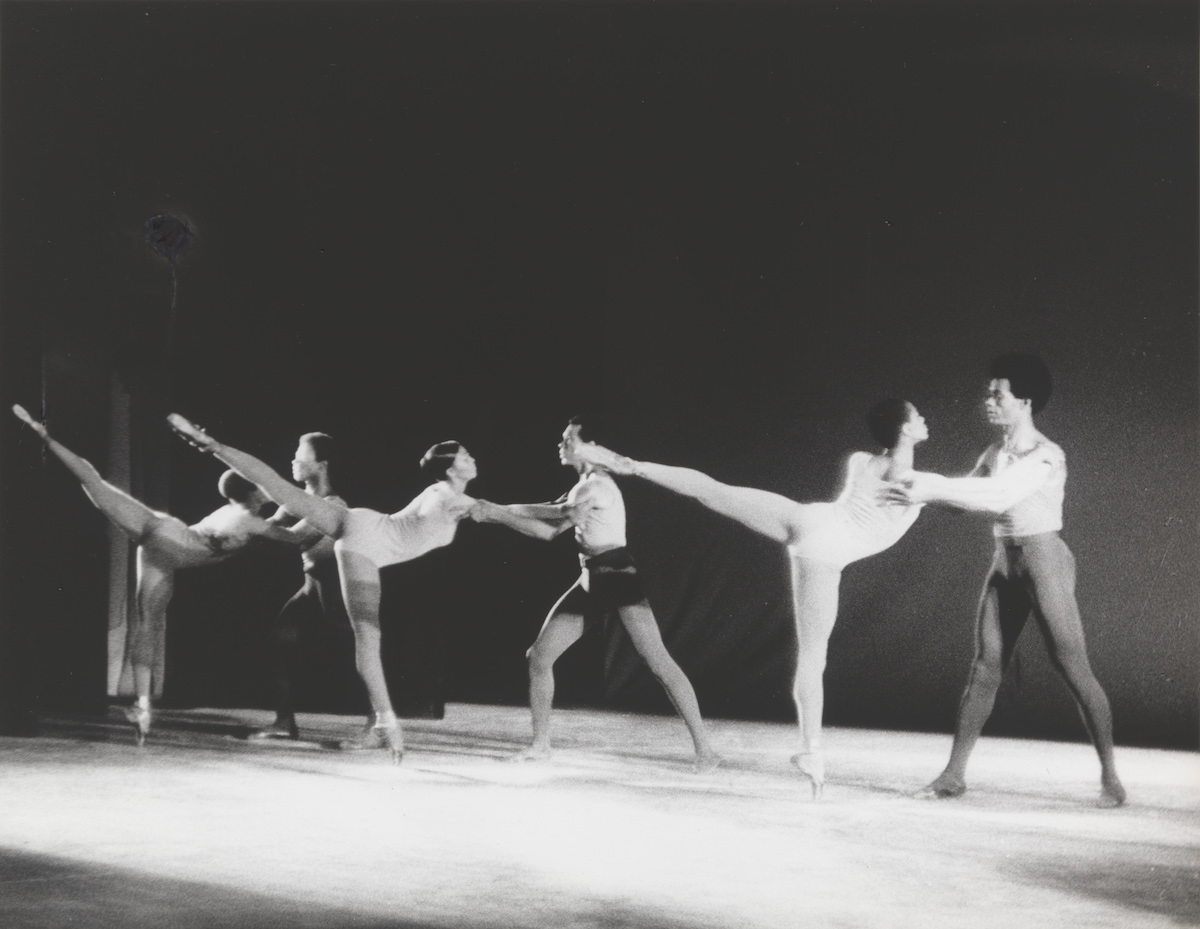

By the first decade of the new millennium, the company had been consistently acclaimed for the artistic excellence that was showcased in its diverse repertory. It included classical and neo-classical works, as well as works that were remarkable for their fusion of several different genres of dance including modern dance, jazz dance, and dance forms reflecting different cultures of the African diaspora. The company’s 2013 repertory at the Pillow was a prime example of its multi-faceted aesthetic. There was Agon (1957), one of several masterworks that George Balanchine had generously contributed to the company’s repertory. With a central pas de deux that Balanchine had originally choreographed for Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams, Agon has been hailed as an iconic work of art that crystalized the choreographer’s modernist approach to twentieth-century ballet. Moreover—as Mitchell remembered in his 1997 interview at the Pillow—there were a number of instances when Balanchine quietly, but persistently, implemented the racially progressive ideas reflected in the work’s casting. For example, he refused to acquiesce when a television producer questioned the inclusion of the interracially-cast Agon in an upcoming broadcast. In his interview, Mitchell also made the revelatory observation that Balanchine was keenly aware of the interplay of contrasting skin colors as he choreographed the work.Arthur Mitchell, Blacks in Ballet and the Rise of Dance Theatre of Harlem—PillowTalk.

One could speculate that Virginia Johnson had Balanchine’s aesthetic of contrasting skin colors in mind when she cast Swan Lake (Act III Pas de Deux). The dancers who performed on Friday, June 21—Michaela DePrince and Samuel Wilson—were a stunning interracial visualization of the ballet’s key roles, Odile and Prince Siegfried. They embodied the simmering passion and sparkling virtuosity of the iconic work in a way that would have been hard to imagine in 1895, when Marius Petipa revived Swan Lake for St. Petersburg’s Imperial Ballet. Moreover, there would be few major ballet companies that would use such a cast during the late-twentieth or the early twenty-first centuries, because the female roles in classical and romantic ballets have always functioned as representations of the ideal beauty of womanhood. They have, consequently, been especially guarded against being undertaken by women of color.

The 2013 program continued with Alvin Ailey’s lyrical and meditative choreography for The Lark Ascending. His company women had always performed his choreography in soft slippers; but this DTH performance was noteworthy, because it was the first time that the female cast members wore pointe shoes.

The following work, John Alleyne’s Far But Close (2012), was described in the program notes: “A unique collaboration that brings together a commissioned score, spoken word text, and innovative choreography. Far But Close stretches the boundaries of ballet to tell an urban love story about the healing power of romantic love.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance presents Dance Theatre of Harlem—Ted Shawn Theatre—June 19-23, 2013, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

The program closed with yet another shift in aesthetic direction. Robert Garland’s Return (1999) was a joyful display of movement drawn from the vocabulary of classical ballet, African-American vernacular dance, and modern dance. At the risk of being presumptuous, I believe that Arthur Mitchell, Virginia Johnson, and all of the choreographers and dancers who contributed to the evening’s program took a special delight in their multi-lingual approach to concert dance. As I viewed a recording of the evening’s performance, I was certainly delighted to see the same dancer who starred as the Black Swan, Michaela DePrince, open Return as she danced and “switched” about the stage. (“Switch” is a southern, black vernacular term for a saucy walk that is not only flirtatious, but extremely self-confident.) She was shortly joined by four other women who multiplied the effect of their playful sensuality. The dancers’ perfect timing illuminated the interplay between academic ballet steps and steps that would more often be performed at nightclubs and high school dances. The Soul Train line near the end of Return was a perfect touch of insouciance.

Beginning in the 1920s with dance artists like Hemsley Winfield, black choreographers have embraced a wide array of African-American music as an important part of their projects. Jazz, gospel, blues, and other types of black music often functioned to underscore the subject matter and the emotional import in works like Alvin Ailey’s Blues Suite and Donald McKayle’s Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder. On the stages of mainstream concert halls, the validation of those musical forms —along with the vernacular dance movement that paralleled them—was part of the sociopolitical/aesthetic reconfiguration of cultural hierarchies that black artists accomplished over the decades. When DTH dancers performed to Aretha Franklin’s soulful melismas and James Brown’s shrieks and shouts, they were part of a tradition in which black choreographers honored a peoples’ rich musical heritage.

When DTH returned to the Pillow the following year, Scholar-in-Residence Maura Keefe spoke of “…the company’s continued interest in plumbing the range of ballet in the 21st century.”Maura Keefe, Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance presents Dance Theatre of Harlem—Ted Shawn Theatre—July 9-13, 2014, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. The first work on the July 2014 program was Ulysses Dove’s Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven: Odes to Love and Loss. He had choreographed the piece in 1993 for the Royal Swedish Ballet. As Virginia Johnson recounted in a post-performance talk, she saw that company perform Front Porch when she was visiting the Pillow in 2004,The work was also performed at the Pillow by the Pacific Northwest Ballet in 2009. and she envisioned it being set on her company. She later invited the executor of Ulysses Dove’s estate, his brother Albert Dove, to see DTH perform at the Pillow in 2013, after which she received his permission to acquire the work. Johnson was extremely pleased, especially since she and Ulysses had been planning for him to choreograph a work for the company, shortly before he died in 1996. As she remarked after a 2014 performance, “It’s really very special that we get to do it in this engagement, because it really came full circle, here.Virginia Johnson, Post-performance Talk—DVD recording # 5209—Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Dove’s remarkable career included performing with Pearl Lang, Mary Anthony, Anna Sokolow, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, where he was singled out for his powerful stage presence. From 1980 to 1983, he served as the assistant director at the Groupe de Recherche Chorégraphique de l’Opéra de Paris, after which he began an extensive career choreographing in Europe, Canada, and America. Pillow audiences first saw his work in 1990, when the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company performed his riveting delineation of religious ecstasy, Vespers.

Choreographers don’t always provide us with an in-depth explanation of what a particular work is about; and—for many artists—that is understandably just as it should be. However, Ulysses Dove left us with his intense reflections on the making of Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven. He shared his thoughts in a 1995 documentary film, Two by Dove. Two by Dove was first aired March 1, 1995 as a part of the PBS “Great Performances/ Dance in America” series. It was produced by Margaret Selby. I am including almost the entirety of his commentary, because his words are as crystalline as the choreography he created for the piece:

Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven is one of the most personal things that I’ve done. The year before I did it, I lost thirteen people who died—my father being one of them. And it just seemed…and then when it started, it seemed like to be a never ending falling of dominos. It just seemed like there was never a moment to just rest and regroup from this constant, endless loss of people. And it went on for a period of about two years. And then, all of a sudden, I reached this point where I had to come to some kind of terms with the issue of loving people and losing them.

…The piece has four sections, and the first section—which is a section about love—is about giving over some major part of ourselves to someone for a kind of eternal care. The second section, which is a male duet, is about friendship. It’s about friendship that is so deep that nothing, nothing comes between two people, not even death. The third section is about loss. I wanted to celebrate the lives of these people that I was dealing with the loss of. I wanted them, wherever they are, to know that the fact that they passed through this world was enough reason to make a ballet. And the last section is about letting their spirits go. Now that we’ve justified their lives, they can go on to other lives. Because they’re…you know…I have this feeling that people can’t go on until they’ve been loved. So it’s a very touching thing; and yet, it’s so joyous; you know, it brings out so many emotions; and yet, one of the emotions is joy.

It was the first time that I feel like I used dance to heal myself. It was the most amazing thing. When it was all finally done and finally premiered, I never felt such a sense of healing, such a sense that I was so much better for having done this piece than I would have been for not. I had made my peace with this issue.

The thing that I feel about dance very strongly, is that dance is definitely about form, but it’s definitely about feeling. And the marriage of those two things are wonderful. It’s about heart. It’s about spirit. It’s about…it’s about everything thing that we could use to describe ourselves as human beings. You know, “What makes me human?” The answer to that is the answer to dance.

The balance of DTH’s 2014 program consisted of past-carry-forward, choreographed by two former members of the company, Tanya Wideman-Davis and Thaddeus Davis, and Contested Space by Donald Byrd. In the program’s PillowNotes, Maura Keefe described Byrd’s work: “…[R]arely do the dancers perform quietly, with soft edges to their bodies. Rather, they consume the movement challenges Byrd feeds them, arms and legs eating up vast distances, becoming larger as they radiate power, drinking in the energy from the space around them and sharing it with us.”Maura Keefe, Program—Jacob’s Pillow presents Dance Theatre of Harlem—July 9-13, 2014.

Another important event at the 2014 season of the Pillow was an interview of black ballerinas from different generations, Virginia Johnson and Misty Copeland. The younger dancer spoke of the shock of entering American Ballet Theatre—a company of eighty dancers—and discovering what it was like to be the only African-American woman in the company. In their anecdotal accounts of their experiences, the two artists reflected on a number of other matters related to race, including the continuing role that skin color plays in the world of ballet.Virginia Johnson and Misty Copeland, Black Ballerinas: What’s New—2014/07/12—DVD ID# 5225—Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Virginia Johnson and Misty Copeland’s discussion of racial issues in the arts was refreshing. As I discussed earlier, those issues are correlates of ideologies that are deeply imbedded in our social and political structures. The beauty of the two artists’ conversation—as they sat framed by the lush summer greenery of the Berkshires, on the deck adjacent to the Jacob’s Pillow Archives—is that they were engaging in an open, honest dialogic process that has so often been denied because of the blind acceptance of unquestioned historical precedents. The fact that their exchanges took place at that particular site underscores the importance of the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival as a place where diversity can be danced and discussed.

A Brief Closing Note

As was the case with several of the essays I have written for the Dance Interactive series, my project covering African-American participation in ballet at the Pillow turned out to be a situation where I “bit off more than I could chew.” So, I feel the need for this disclaimer. No comprehensive discussion of black ballet artists at the Pillow would be complete without including the phenomenal work of Alonzo King. The Archives contain extensive documentation of an artist whose company has brought his unique vision to festival audiences beginning in 2000, when Scholar-in-Residence Suzanne Carbonneau wrote the following about his choreography:

The dancing literally muscles its way in with an insistent physicality that celebrates flesh and blood, pointing up the quaintness of traditional balletic languor, a relic of days when women were idealized as immaterial. Its equalizing of gender roles and of male and female techniques hustles ballet into the postfeminist world. It celebrates the gains to be made in risk-taking and rule-breaking: transposing and inverting bodily shape, folding lines in on themselves activating a fluid spine. It celebrates daring, energy, freedom, and forcefulness, rejecting dancing that is “correct” for dancing that is impulsive. The only thing it reveres is pushing into the unknown.Suzanne Carbonneau, Program—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Ted Shawn Theatre—August 23-27, 2000—Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Carbonneau’s incisive description of the movement language King creates on his dancers captures some of the qualities that make his aesthetic vision unique in the world of ballet. Moreover, the philosophical and spiritual beliefs that have always guided his artistic endeavors reveal a cultural worker/citizen/artist of the world who embraces the fullest potential of humankind. That he has repeatedly shared his work with audiences at Jacob’s Pillow seems especially meaningful. But, at this point, I have to concede that I need to write another essay in order to adequately consider King’s remarkable body of work.