The following essay is an expansion of a 2023 summer exhibition of the same name curated by guest curator and founder of Final Bow for Yellowface, Phil Chan, and Costume Curator Caroline Hamilton.

Preface

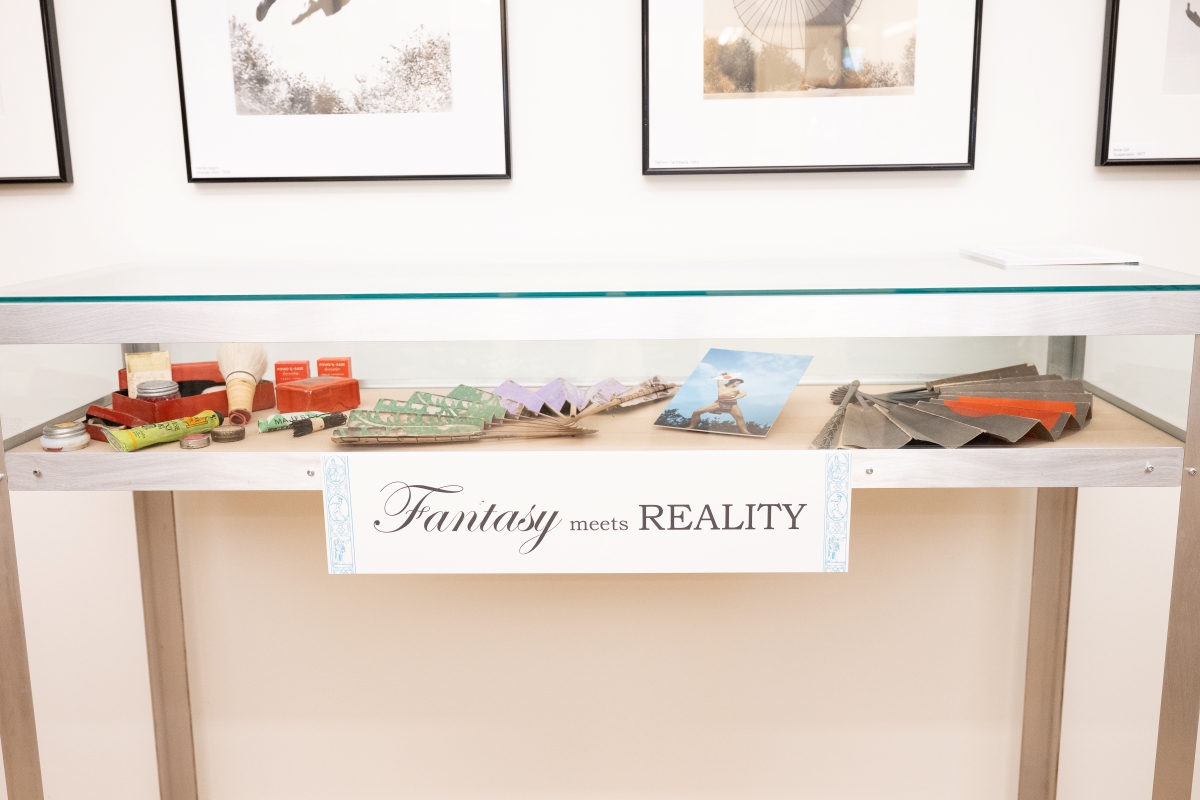

This exhibition and essay wrestle with the concept and legacy of both cultural appreciation and appropriation through the lens of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn’s tour to Asia in 1925-1926. While we can’t accept the creative process of their time as contemporary models for crossing cultures with integrity, taking a closer look at these objects with nuance and curiosity can provoke questions and discussion on the best way artists today can do so with grace and respect.

This project was the result of a Pillow Lab undertaken in January 2023. During our residency we sought to look at the work of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn through the surviving material culture – namely items form the extensive Jacob’s Pillow Costume Collection, which encompasses more than 2,500 items created between 1906 and 1940. We chose to focus on the company’s Far East Tour of 1925-26 as a way to examine the Denishawn company and discuss the duality present when faced with items from the collection. This was Phil’s first visit to Jacob’s Pillow and the archive – while I, on the other hand, had been working with the collection for over five years. Our two voices, approaches, and perspectives have come together in this project.

Reflections from Phil Chan:

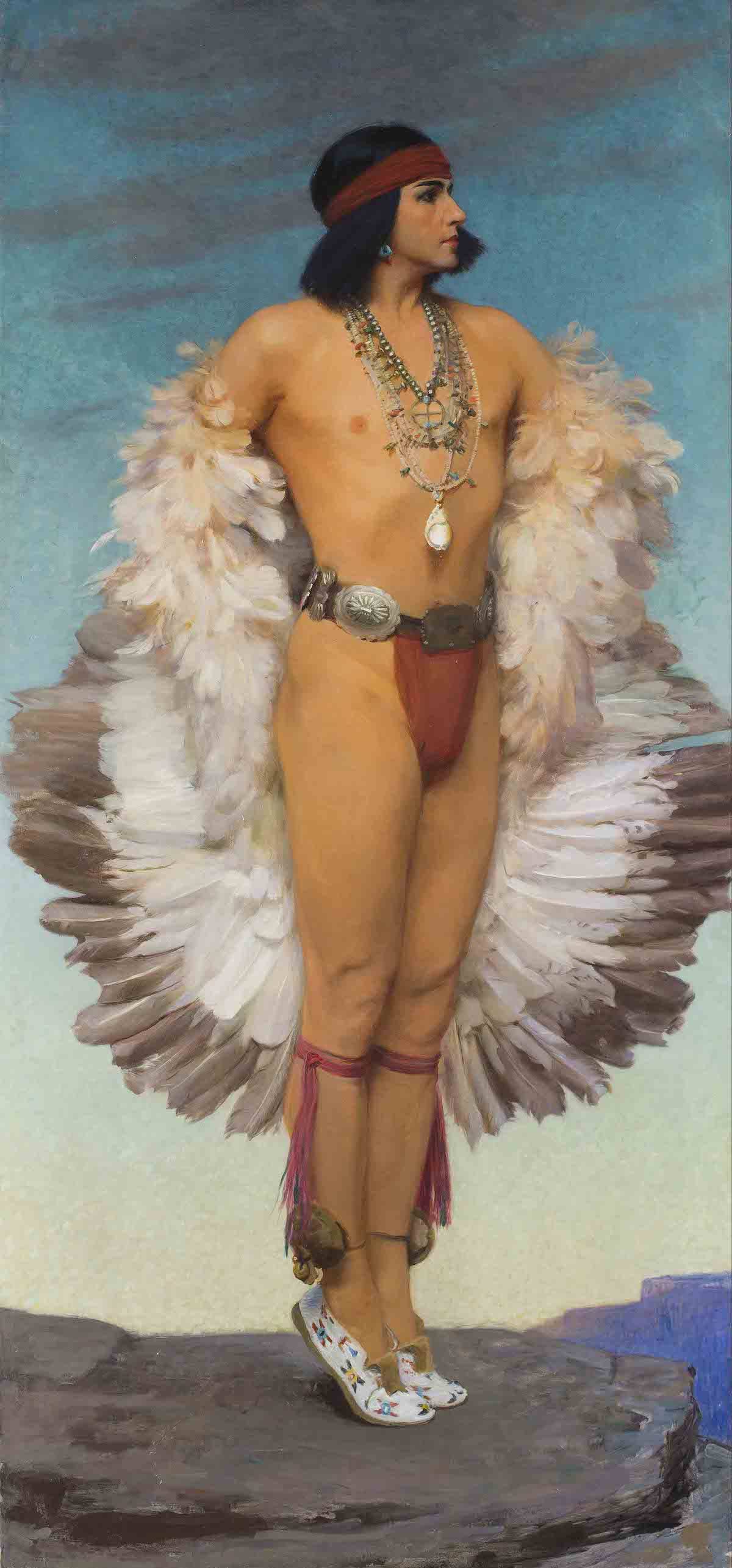

“Be warned,” a colleague mentioned to me cryptically, “when you walk into the archives at Jacob’s Pillow, you will be greeted by these giant portraits of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. Just giving you a heads up…” Sure enough, as I stepped into the archives, there was Papa Shawn, dressed as a scantily-clad Native American, and Miss Ruth as the Chinese goddess Guan Yin. I sat with my discomfort for a moment — seeing a white woman dressed as the closest thing I (and many Asians) have to a patron saint. As I read the labels, containing both historical context and reflections on the impacts of these works, I couldn’t help but also notice how well-crafted the paintings were; they were also beautiful. I sat with that discomforting paradox for a while.

Reflections from Caroline Hamilton:

I have been working with the Pillow’s costume collection for five years. I unpacked each item from the steamer trunks where they had resided for decades. I assessed, catalogued, re-packed, and even hand sewed a label into every item. I have touched (and smelled) every one of the 2,500 items. I have got close to these objects both literally and figuratively – I have felt their weight, volume, and have examined them through a magnifying glass, counting threads, and looking at stitching. I have also become familiar with the bodies that are now absent – I have measured in detail many of these costumes and have customized and fabricated mannequins to fill this void based on exact measurements. I have come to know these objects and the bodies that once filled them – they became friends and partners in my work. This closeness has meant that I have been able to see and record minute details and understand how these costumes were made and worn. This project has allowed me to take a step back, look at the bigger picture and come to terms with the discomfort that this sometimes creates. These pieces can be beautiful – incredibly made and used for decades – but also uncomfortable and problematic in their creation.

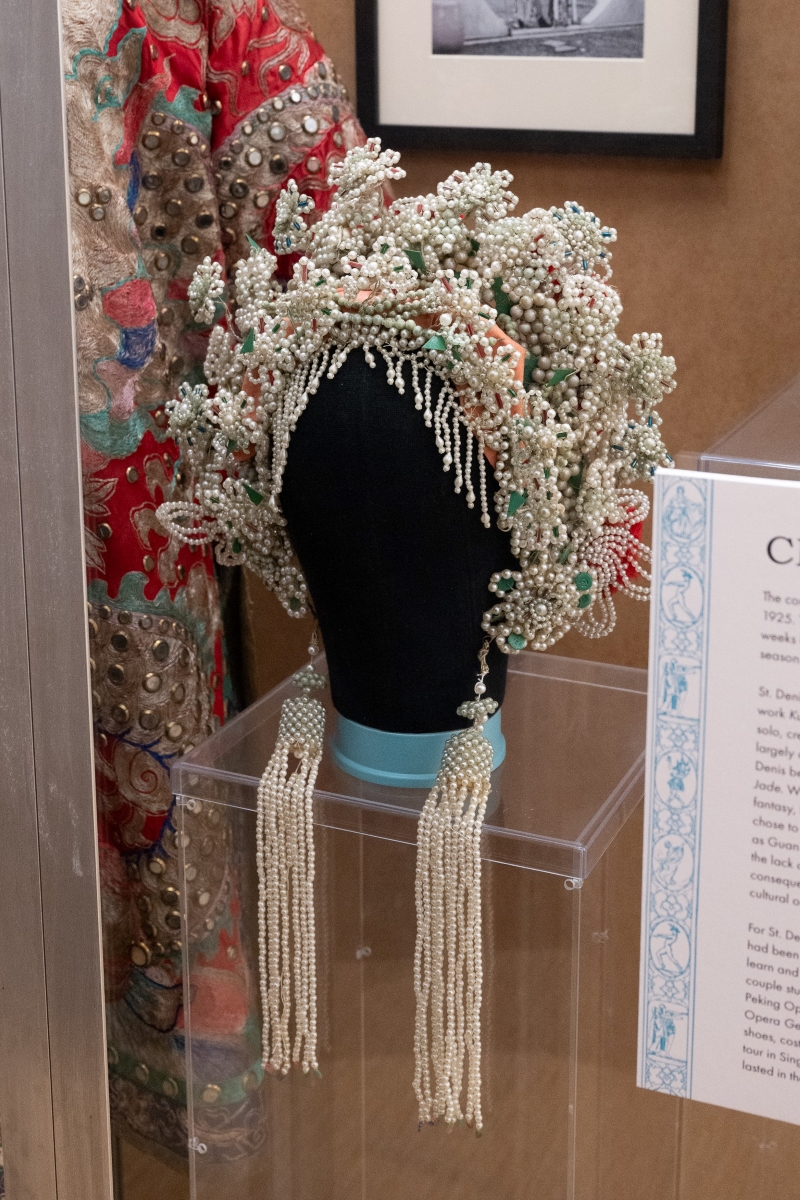

The pieces selected for the exhibition and essay reflect the grey area between appropriation and appreciation, highlighting the line between fantasy and reality while inviting viewers to question issues of authenticity versus integrity and how culture is performed through the dancing body. It’s possible to compare early fantasy Oriental depictions, pieced together from brooches and other costume jewelry, with the actual Asian theatrical pieces that were customized for the company dancers.

Phil and I hope that you examine the images with curiosity and can also sit with the discomfort that something might be beautiful and also culturally problematic, and that the larger racial dynamics might be appropriative while also simultaneously bringing about greater inclusion by opening doors for Asian artists in the future.

Introduction

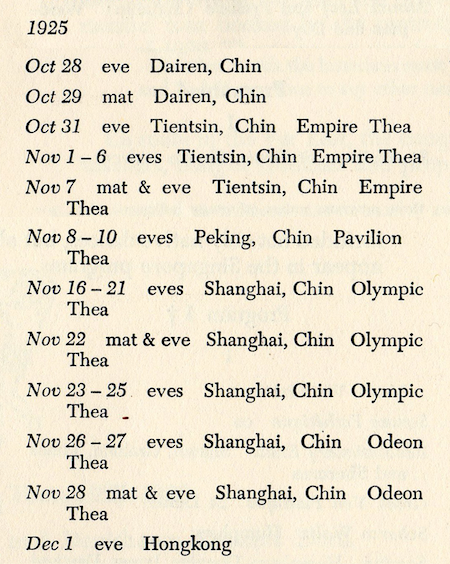

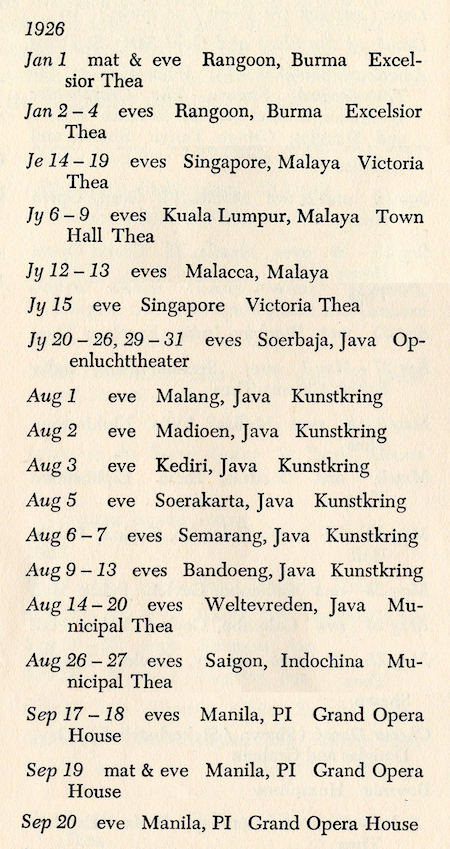

Over 15 months beginning in September 1925, the Denishawn company, led by St. Denis and Shawn, toured to over 12 countries across Asia. For the preceding twenty years, St. Denis had made her career drawing from the cultures of these countries but until now had never visited. Until this tour the works created by Shawn and St. Denis were largely fantasy, and while they were drawn from research into literature, art, sculpture, and even conversations with citizens of these countries when they could be found, the results were still a fantasy.

Reflections from Phil Chan:

A big part of my work as an advocate, scholar, and artist is looking critically at Eurocentric works from the past to understand the impact of the legacy on the artists today living in diverse societies. Often, I come across a particular body of work that deserves attention, even if aspects of it don’t sit right with today’s audiences. We can’t accept them as models for contemporary work, and yet we also can’t cancel them as though we have nothing to learn from them. We’re required to look at these works with nuance and curiosity, and as much as possible, on their own terms. This exhibition [and essay] reveal the problematic aspects of the work of Denishawn as well as pointing to the possibilities, even if unrealized, of allowing artistic traditions from one culture to be informed by those from another.

Dances about “Fantasy Asia” had been a mainstay of European (Western) ballrooms and stages ever since accounts of “the Orient” captured the imaginations of cultural elites in Europe hundreds of years ago. Denishawn followed a long tradition of inventing exotic settings and characters of the supposed “Orient,” presented for the fascination of European audiences. Orientalist works have been based on incomplete information and little or no encounter with the cultures they claimed to portray, and that’s a problem for audiences today, when we are diverse and more worldly—when fantasy meets reality, to the detriment of fantasy.

In 1925, these fantasies met reality. The company initially chose not to bring many of their Asian works on the tour, unsure of the reception. However, they added back in many of these works throughout the tour and created a number of new works – significantly more ‘authentic’ than those produced before. These works drew from what the couple was seeing and learning while on tour and contained elements of authentic story, choreography, and costumes. These works included: Momijii Gari, White Jade, General Wu’s Farewell to His Wife, A Javanese Court Dancer, A Burmese Yein Pwe, The Cosmic Dance of Siva, and In the Bunnia Bazaar.

Reflections from Phil Chan:

At the time, culturally authentic Asian dances were mostly relegated to Coney Island sideshows as barker curiosities or billed as some form of low burlesque. Due to her race, St. Denis was able to raise the tone, and thus, slightly elevated respect for the cultures she purported to portray; she danced in a way that an Asian woman of the time would have not been allowed to. She performed Radha to music from Delibes’ Lakmé, as she didn’t have access to Indian music. Perhaps that also had the untended consequence of making the dances more palatable to White audiences? Even if the dances were the choreographic product of St. Denis, and not of an Asian choreographer working within a specific heritage and discipline, Asians at the time might have seen a cultural ally in St. Denis compared to some of her more appropriative White performers. This process wasn’t without its faults. The Asian supporting dancers St. Denis hired, such as the four men in Radha, remain otherwise anonymous bodies supporting her, now immortalized on film.

A collision between fantasy and reality is inevitable when artists present inauthentic portrayals of cultures they know little about. Denishawn’s Far East tour changed this dynamic in their work. We see a nervousness and hesitation at first in the repertory they chose to bring. After encountering authentic Asian dances in China, Japan, and India, we see Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis shift from wanting to present dime-store goddesses to learning and presenting actual Asian dances. We see this evidenced by the works they created while on the road in Asia; at every stop they commissioned and purchased authentic costumes for these new ballets. They were clear that while the works were products of their creative output, these were authentically informed dances sourced directly from the Orient.

The Far East Tour was produced by Shanghai based Russian émigré Asway Strok, who had also managed Anna Pavlova’s successful East Asia tour in the early 1920s. The touring Denishawn company consisted of:

- Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn

- Doris Humphrey

- Pauline Lawrence

- Ernestine Day

- Ann Douglas

- Georgia Graham

- Jane Sherman

- Mary Howry

- Edith James

- George Steares

- Charles Weidman

- They were joined by Grace Burrows and Ara Martin, who according to dancer Jane Sherman ‘paid their own way to study the Oriental dancing they wanted to teach back home’.Jane Sherman, Soaring: The Diary and Letters of a Denishawn Dancer in the Far East, 1925-1926, 1st ed (Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press, 1976). 11.

The company also included:

- Clifford Vaughan – conductor/composer – who led an orchestra of White Russian musicians organized by Strok.

- Brother St. Denis – Ruth St. Denis’s brother who acted as stage manager and an extra, when needed

- Stanley Frazier – master carpenter and chief electrician

- Pearl Wheeler – wardrobe mistress, costume designer, dresser

- Wheeler was helped on the tour by Doris Humphrey’s mother, known as ‘Lady’ Humphrey. In Tianjin the company also hired China Po as a tailor-assistant who travelled with the company for nearly a yearSherman, Soaring: The Diary and Letters of a Denishawn Dancer in the Far East, 1925-1926, 11

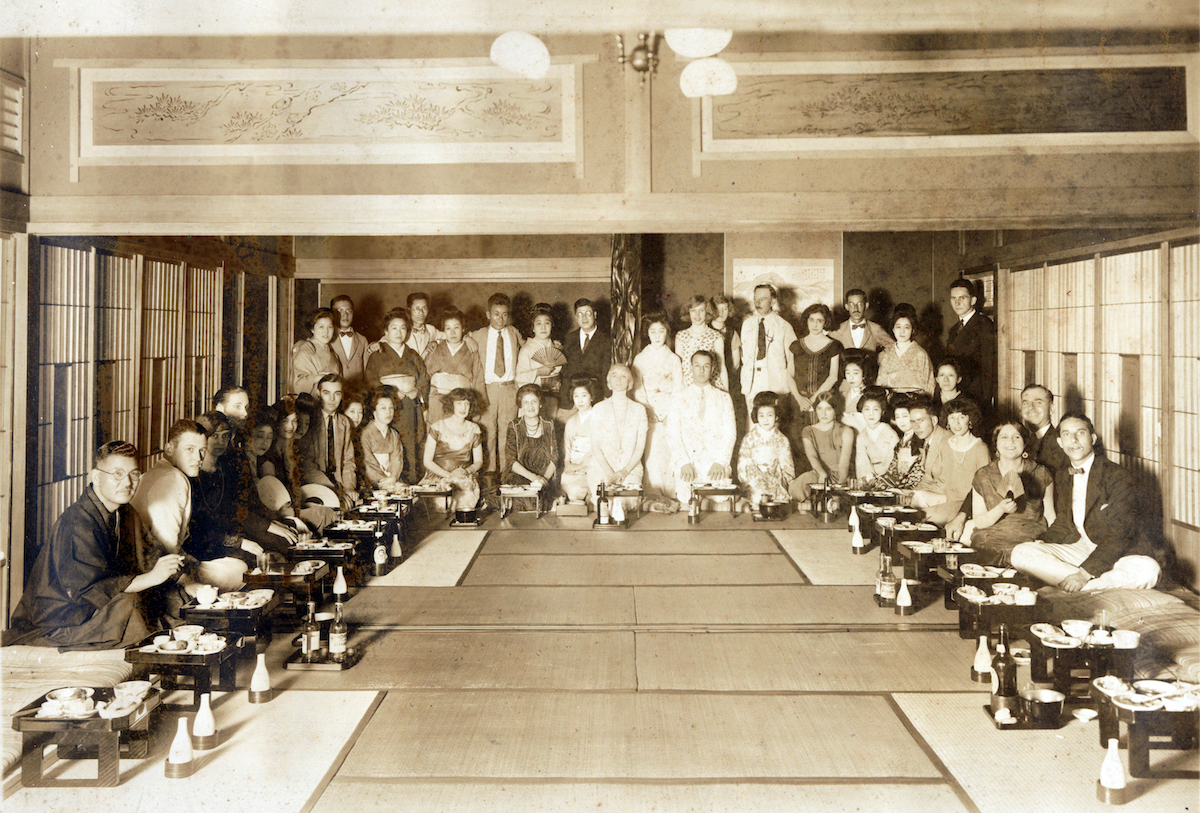

This was the first tour to Asia by an American dance company. The couple and their dancers were hosted by royalty, politicians, and diplomats wherever they went, and invited to a slew of tea parties, soirées, and dinners. They were seen as unofficial American ambassadors.

The following sections of this essay are separated by region, reflecting how the exhibition was divided, focusing on the objects chosen to display.

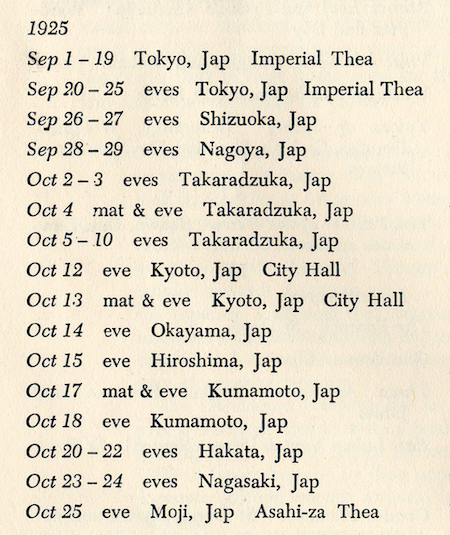

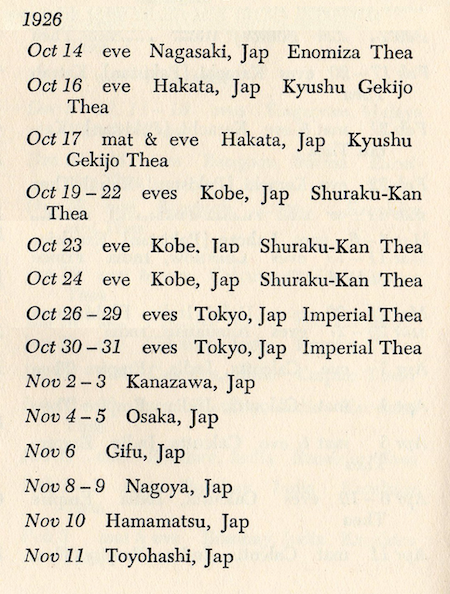

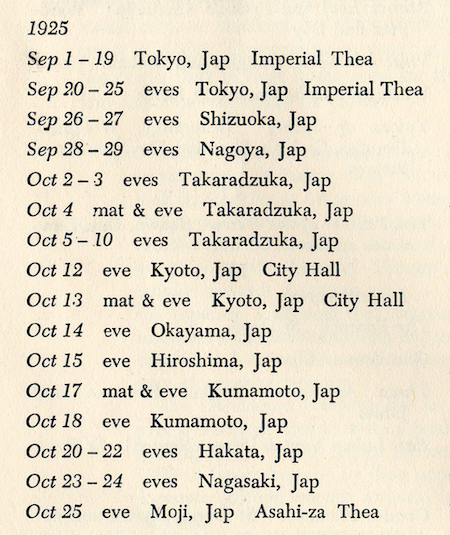

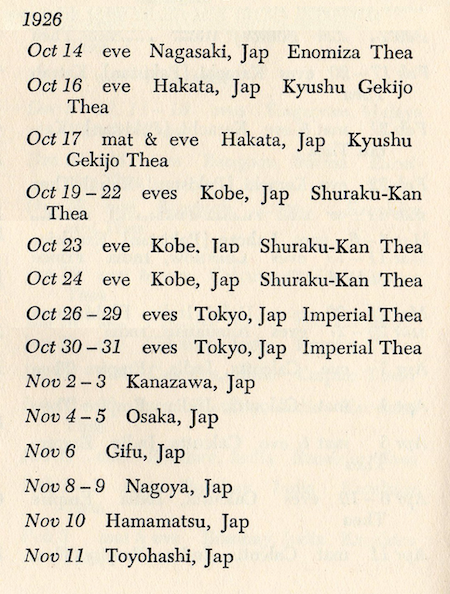

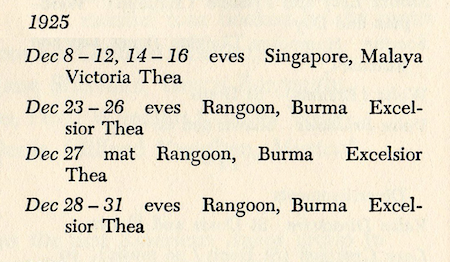

Japan

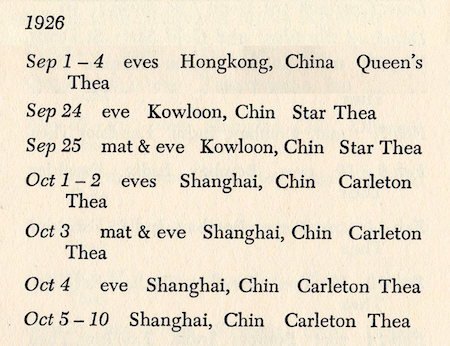

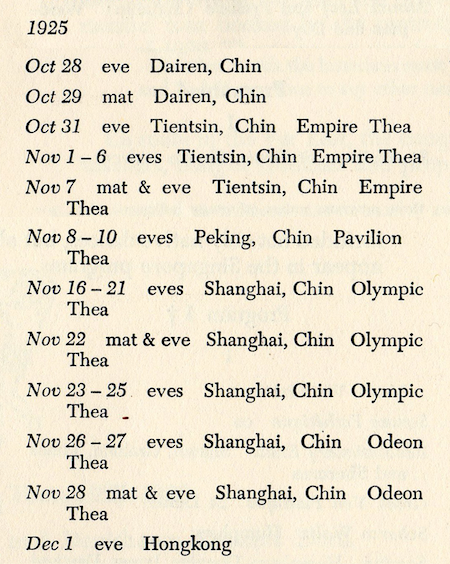

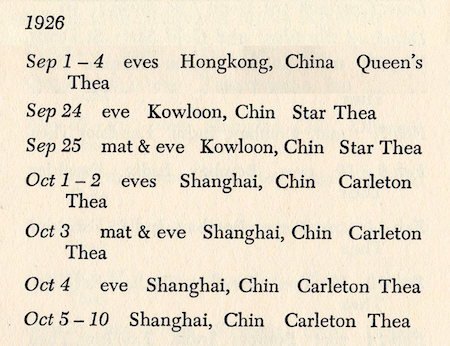

Japan was the first and last stop on the company’s 15-month tour. The tour began in September 1925 with four weeks in Tokyo at the Imperial Theatre and followed by a regional tour covering multiple cities. Denishawn returned 12 months later undertaking a second shorter tour.

St. Denis had first been inspired by Japan in her work O-Mika, which premiered in 1913. In researching this work St. Denis undertook six weeks of lessons with a former geisha in Los Angeles and read as much literature as she could. Although the work had nods to ‘authentic’ movements and gesture, it was largely a fantasy of St. Denis’s imaging. In her biography St. Denis described O-Mika as a ‘little drama with dancing interludes’. A section of O-Mika, entitled Japanese Flower Arrangement, was added to the Far East Tour part way through. St. Denis continued to perform excerpts from O-Mika throughout her career, reviving the whole work in the early 1960s.

Take a closer look:

Part way through the tour Shawn also added one of his own Japanese inspired works. Entitled Japanese Spear Dance, this work had premièred in 1921 with choreography by Shawn and a score by Louis Horst. Shawn performed this solo throughout the 1930s and 40s even after his main choreographic focus had moved towards modern dance.

Take a closer look:

Both works discussed so far were created before Shawn and St. Denis visited Japan. Once the couple arrived, they were inspired to create a new work drawing on what they were seeing. Shawn decided he wanted to create a version of the famous Kabuki dance/drama Momiji-Gari, which he had seen multiple times in Tokyo. Shawn met with actor-dancer Koshiro Matsumoto who agreed to teach Shawn his own role in the work as well as give daily lessons to the company.

Dancer Jane Sherman later wrote:

For four hours every morning … the Denishawn Company took lessons in Japanese dancing, either outdoors on the roof of the Imperial Theatre or in several of its many rehearsal rooms, and always accompanied by samisens [a traditional Japanese three-stringed lute]Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 1st ed (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1979). 151.

Rehearsals for Momiji-Gari began on tour and a new musical score was created by Clifford Vaughan based on the Japanese score. It is important to note that no matter how ‘authentic’ St. Denis and Shawn were trying to be they always used western adaptions of music. When they returned to Tokyo in late 1926 the Imperial Theatre had the costumes, wigs, and props ready for the company. Momiji-Gari premiered in December 1926 in the USA and remained in the repertoire just one season.

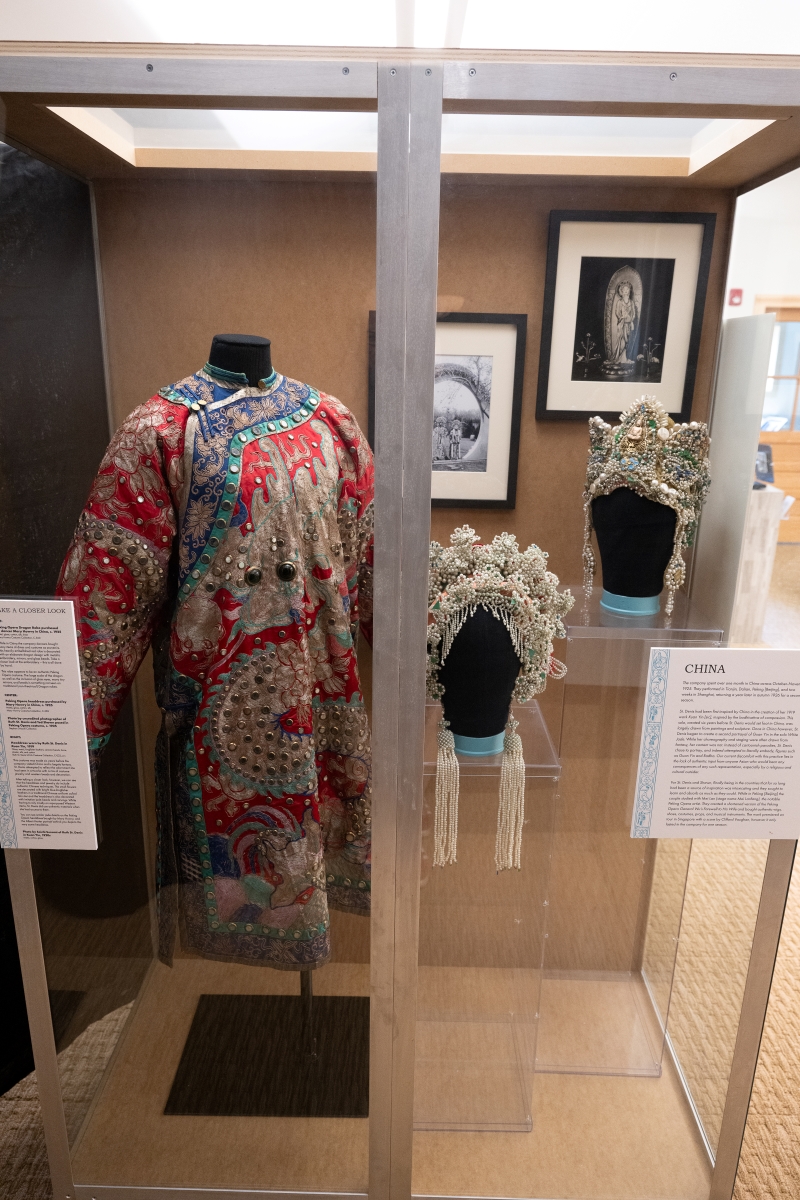

China

The company spent over one month in China in October-November 1925. They performed seasons in Tianjin, Dalian, Peking [Beijing] and two weeks in Shanghai and returned a year later in fall 1926 for a second season.

St. Denis had been first inspired by China in the creation of her 1919 work Kuan Yin [now more commonly translated as Guan Yin], inspired by the bodhisattva of compassion. St. Denis created the solo to Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie #3. Her choice to use Western music reflects both what was available but also perhaps making the work more acceptable to a Western audience. This solo was created six years before St. Denis would set foot in China and is largely fantasy with the choreography drawn from paintings and sculpture. A picture of St. Denis in this role was the cover of the Far East Tour souvenir program, however the solo was initially not included in the repertoire but added in mid-tour. St. Denis’s depiction of the goddess was immortalized in Albert Herter’s portrait. St. Denis created a second portrayal of Kuan Yin in her solo White Jade, which she began to create while in China. This solo, which arguably returned to St. Denis’s earlier fantasy, was the most successful that she brought back from the tour. Sherman would later write:

It is safe to say that, except for White Jade, none of the dances Miss Ruth choreographed after her fifteen-month direct experience of the Far East ever realized her creative aims as well as did those solos she choreographed long before she visited the OrientJane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 137.

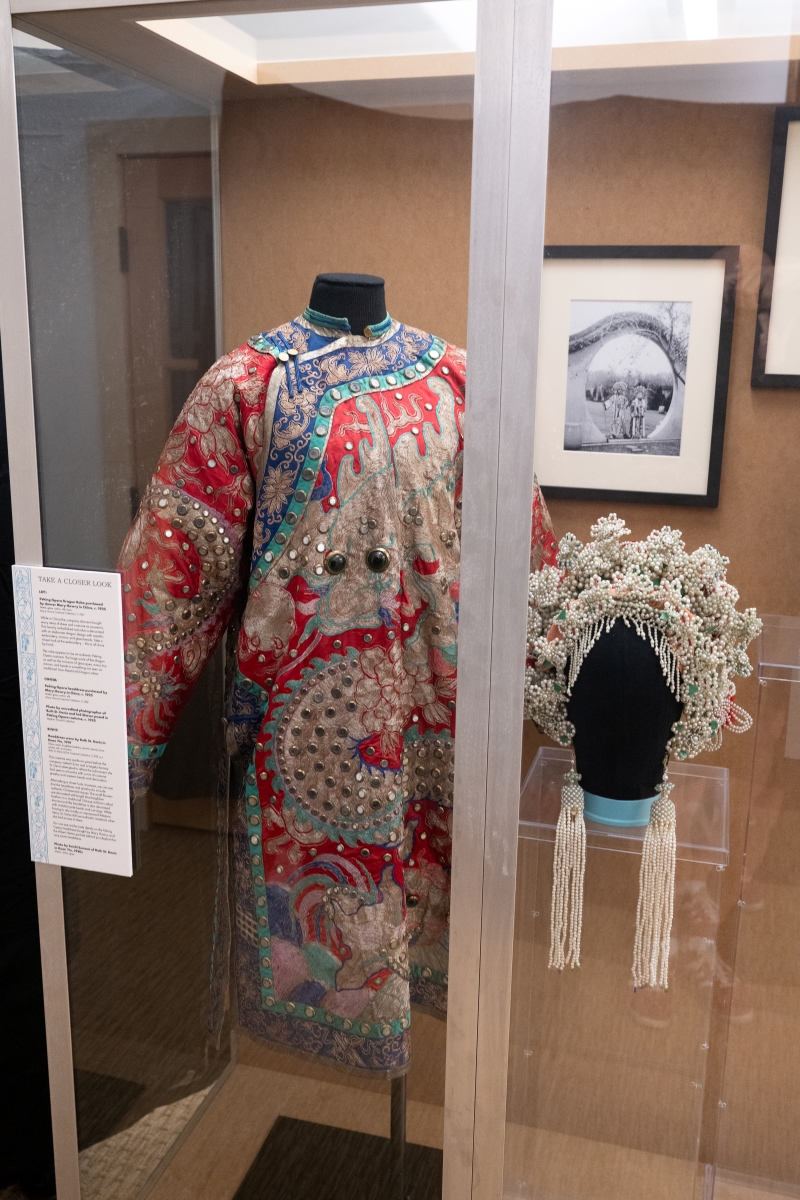

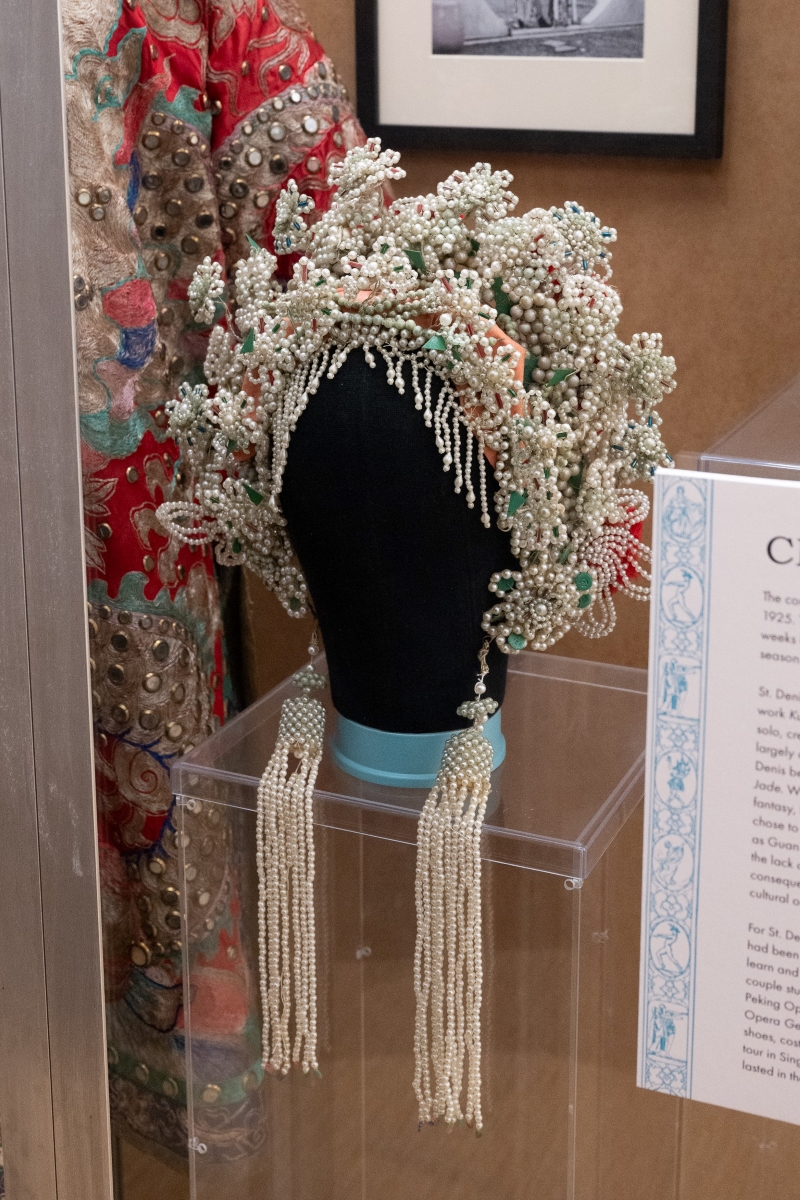

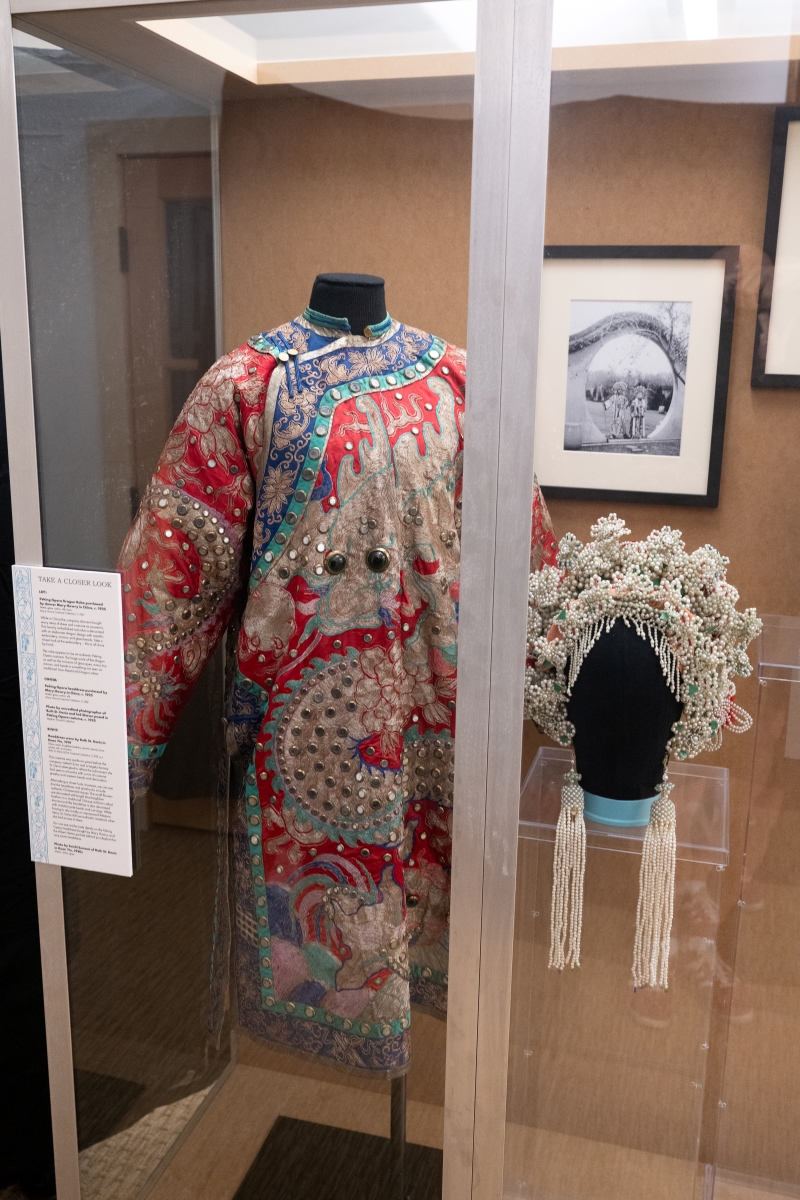

Take a closer look:

When working on this section Phil was struck by the fact that although the majority of the works created by St. Denis prior to the tour contain degrees of fantasy, the figures she chose to portray were not.

Reflections from Phil Chan:

Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis’s early artistic process in Denishawn often involved taking Asian cultural symbols out of context, casually depicting ersatz religious figures and rituals with little or no commitment to authenticity, and a general arrogance about their place as “interpreters” of otherwise exotic cultures. We even see them browning up their skin and over accentuating their eyes to look more Asian. These Oriental dances were among the pair’s most commercially successful and became their most iconic calling cards. St. Denis was heralded as “rescuing this art from the shocking and suggestive, she who gave it vogue.” There’s certainly a lot for contemporary viewers to be offended by!

And yet, despite what by today’s standards is considered cultural appropriation, I’m struck by St. Denis’s cultural curiosity in her artistic practice—a curiosity today’s artists also need to cultivate in order to cross cultural borders with integrity. Initially inspired by a tobacco advertisement set in a faux Egypt and featuring the goddess Isis, she was determined not just to perform dances of the Orient, but to entirely embody those places in spirit. She was voracious in her appetite for learning about other cultures, reading books about them and doing what she could to educate herself by mingling with people of different races. Remember, she did not live in a society with the cultural diversity we enjoy today, nor did she have the same opportunities for authentic contact with other cultures that we do. Yet in spite of this, her dances did not star Princess Gamzatti or Yum Yum (cartoonish parodies),“Princess Gamzatti” is a lead character in the 1877 ballet La Bayadère. “Yum Yum” is a character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1885 production The Mikado but instead involved a personification of Radha. Instead of Ping Pang Pong, she opted for Guan Yin. Despite the recurring theme of compassionate goddesses, neither the Norse goddess Eir nor the Roman Clementia made the cut; for St. Denis, there was something specifically about the Orient that beckoned.

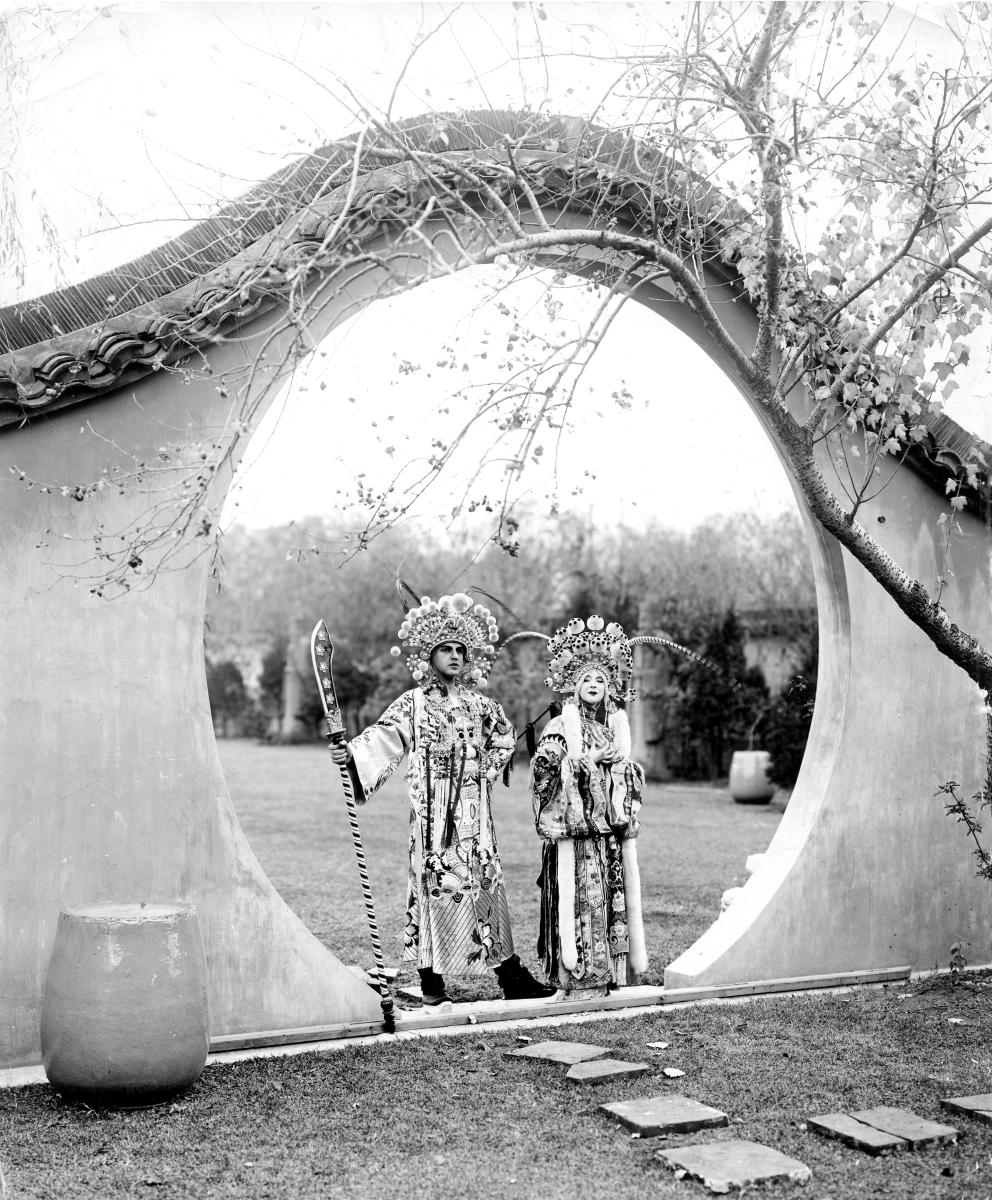

For St. Denis and Shawn, finally being in the countries that for so long had been a source of inspiration was intoxicating and they sought to learn and absorb as much as they could. While in Peking [Beijing] the couple wanted to see Mei Lan (stage name Mei Lanfang), the famed Peking Opera artist. Lanfang was not performing at the time but agreed to perform for the company after one of their own performances.

Dance Jane Sherman recalled:

When we had removed makeup and got dressed, we went out front to sit in the best orchestra seats of the elegant little Pavilion Theatre, where we watched Mei-lan Fan [sic] and his company present an hour of dance selections from General Wu, complete with costumes and makeup. Miss Ruth said she had never seen hands as marvellous as Mei-lan Fan’s [sic] nor dancing so filled with beauty and grace.Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 146.

They were inspired to create a shortened version of General Wu’s Farewell to his Wife for Denishawn and bought authentic wigs, shoes, costumes, props and musical instruments in Peking. Sherman writes that:

… in our three days in Peking, Miss Ruth and Papa managed to make copious notes of the ballet at a three-hour session with Mei-lan Fan [sic]: to buy all the wigs, costumes, headgear, footwear, stage settings, and props: and to arrange for Clifford Vaughan to purchase the instruments needed for accurate sound effects in the score he would write.Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 147.

General Wu’s Farewell to his Wife premiered in July 1926 in Singapore. It was choreographed by Mei Lanfang and adapted by Shawn and St. Denis. Once again, the music was created by Clifford Vaughan. The work like many of the other created on the tour was not performed after 1927 and does not seem to have pleased the American audiences to the extent that the pure fantasy works did.

Take a closer look:

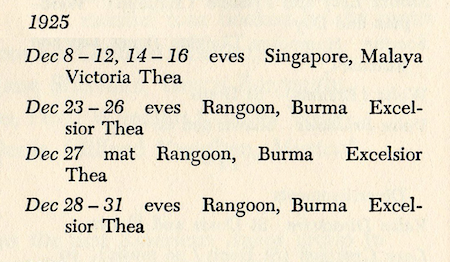

Southeast Asia

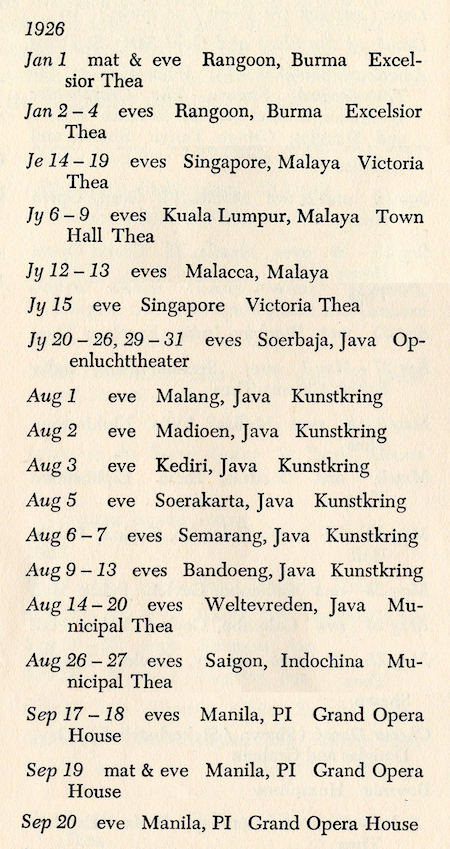

The company toured to six counties in Southeast Asia over six months from late 1925 through 1926. This included Singapore, Burma [Myanmar], Malaya [Malaysia], Java [Indonesia], Indochina [Vietnam], and the Philippines. Southeast Asia had been the source for several fantasy works by St. Denis and Shawn both before and after the tour and was the inspiration for several new dances created on the tour.

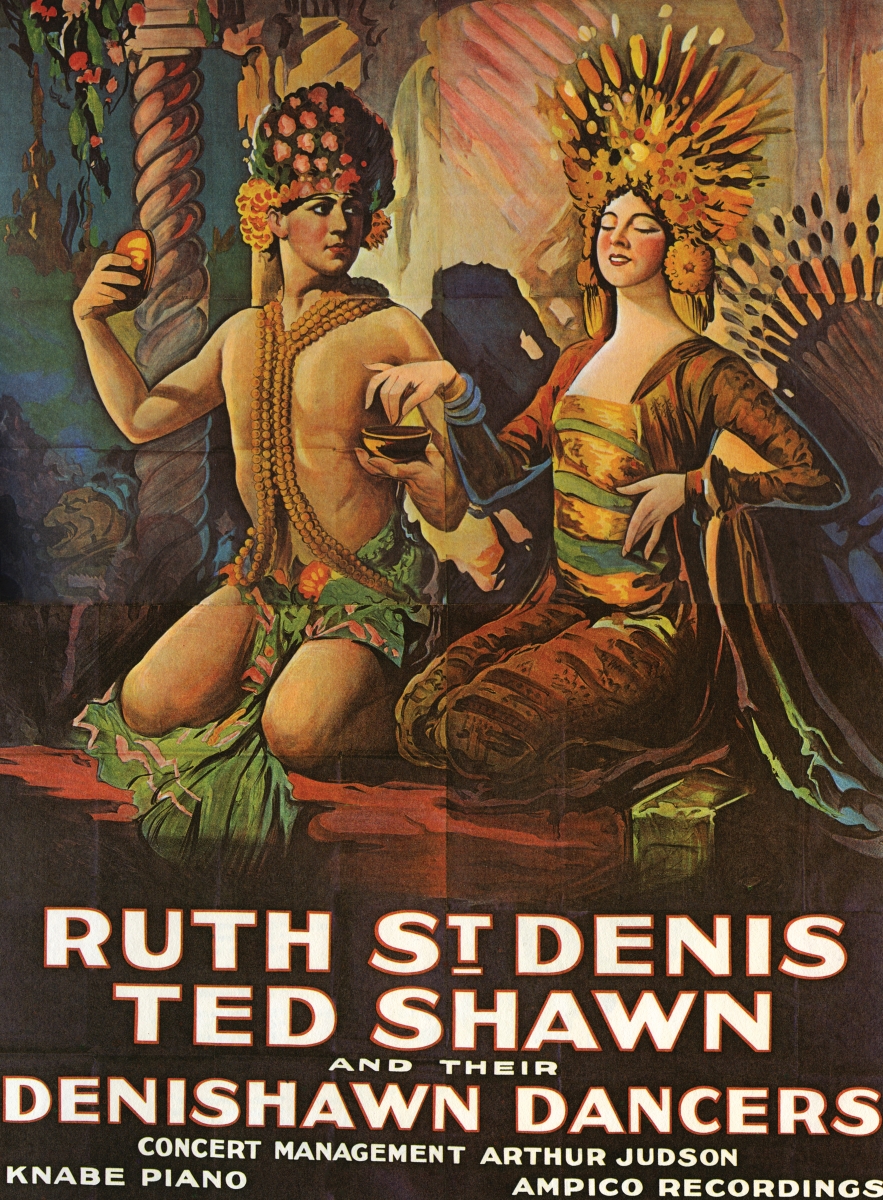

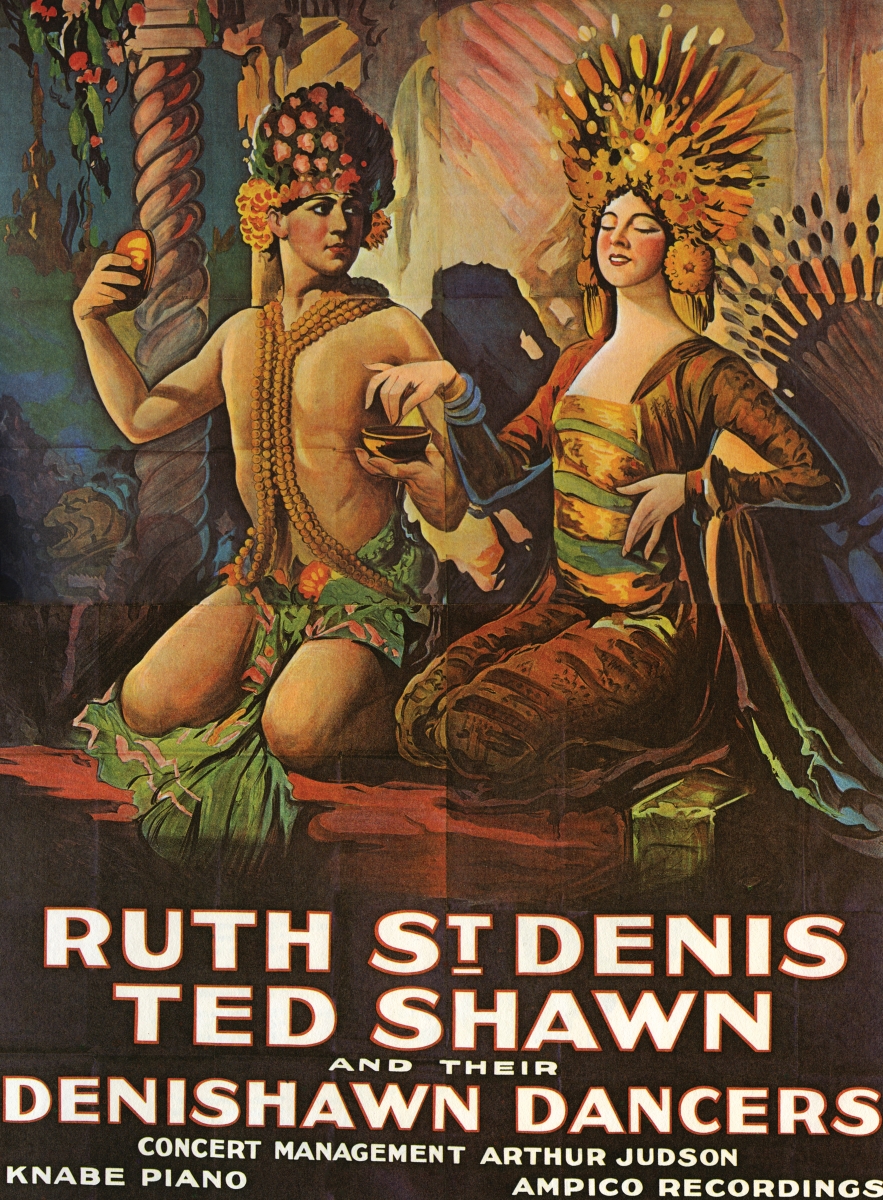

In 1922 Denishawn premiered the Siamese Ballet, which was a reworking of a similar work, Danse Siamese, originated by St. Denis in 1918. In 1924 St. Denis and Shawn created the duet Balinese Fantasy. While inspired by art and sculpture, this work was also largely fantasy and can be seen illustrated in the large poster in the Jacob’s Pillow Reading Room.

Take a closer look:

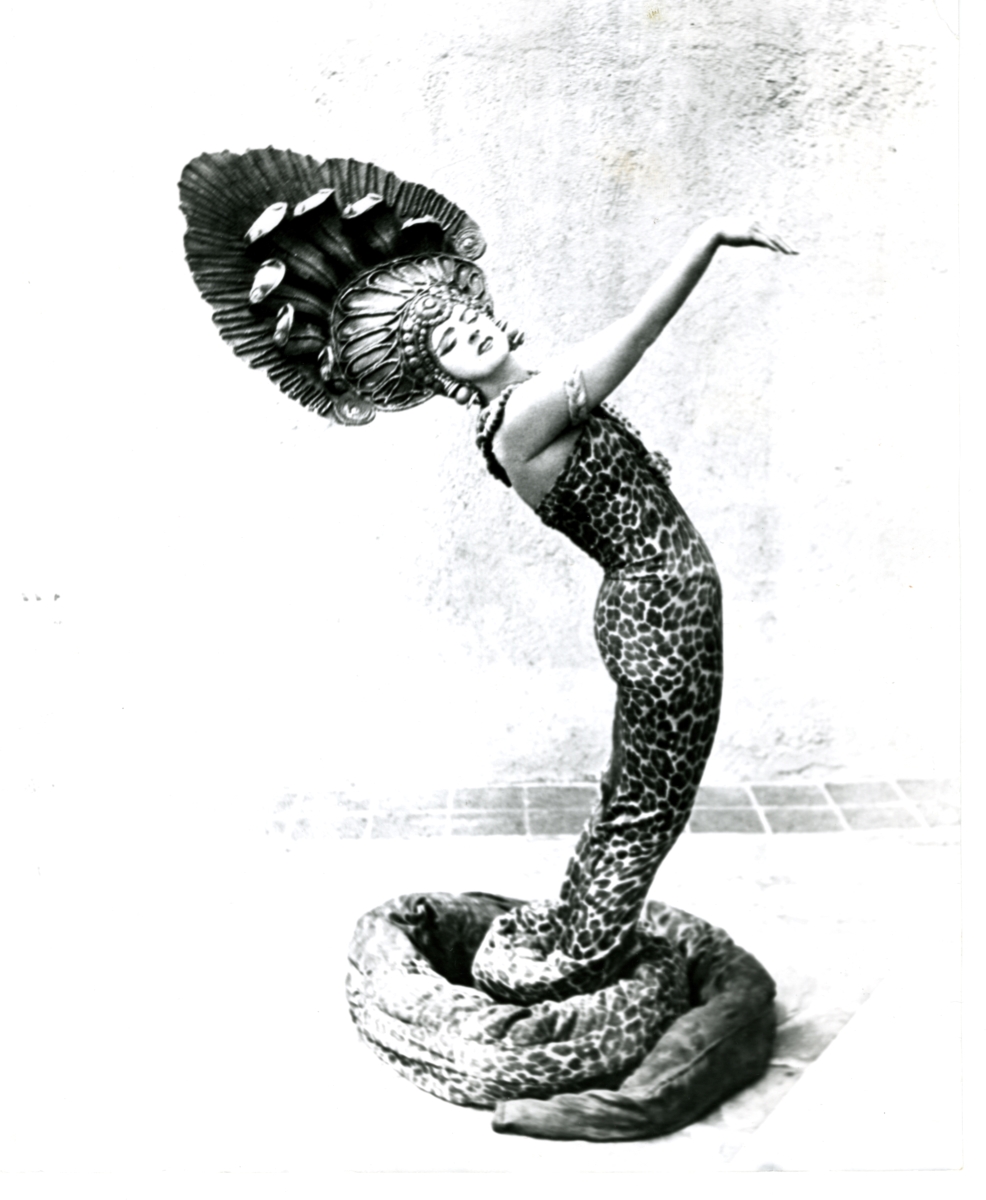

In 1930, St. Denis returned to an imagined version of Southeast Asia in her work Angkor Vat [sic], inspired by bas-reliefs of the Cambodian temple of Angkor Wat, with music by Sol Cohen. These works of fantasy were popular, however while on tour Shawn and St. Denis sought to create works that were more authentic.

Take a closer look:

Dancer Jane Sherman later wrote that works created on the tour were “more a re-creation of an actual event than the choreographing of an impression, an idea, or message, as had been the case in their earlier works on Oriental themes.”Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance,142-3 Perhaps this attempt at accurate reconstruction was why these works weren’t as successful as those of pure theatrical fantasy, or perhaps audiences just weren’t ready for reality. St. Denis created two Southeast Asian works, A Burmese Yein Pwe (together with Doris Humphrey), and the solo Javanese Court Dancer, both of which premiered on tour, with scores created by Clifford Vaughan. Sherman commented on the ongoing conflict between reality and fantasy, writing that:

… despite the undeniable beauty and fascination of this representation, there was a curious lack of the theatrical-spiritual impact which was inherent in most St. Denis solos. Perhaps her preoccupation with authenticity took precedence over her drive to communicate the essence of culture, and perhaps this preoccupation diminished the dance … Certainly these later dances were never as enthusiastically received by audiences as were her earlier and undoubtedly less authentic work.Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 137

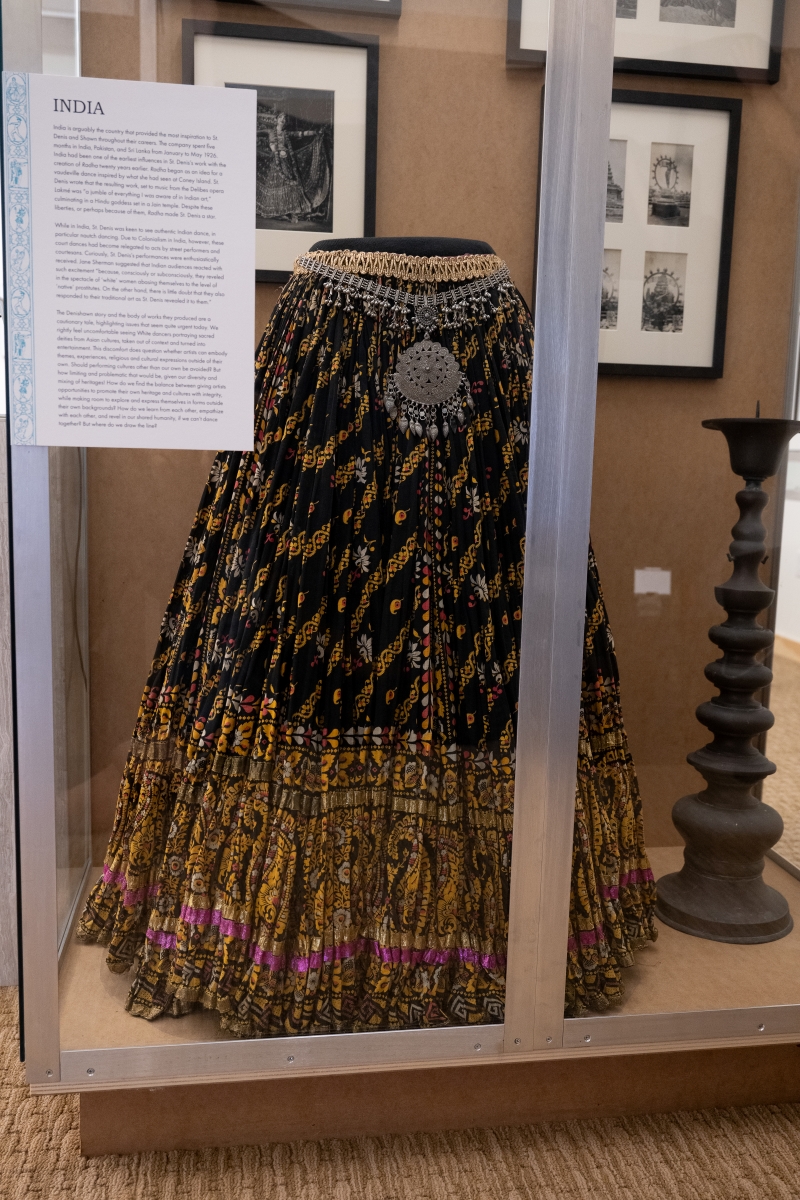

India

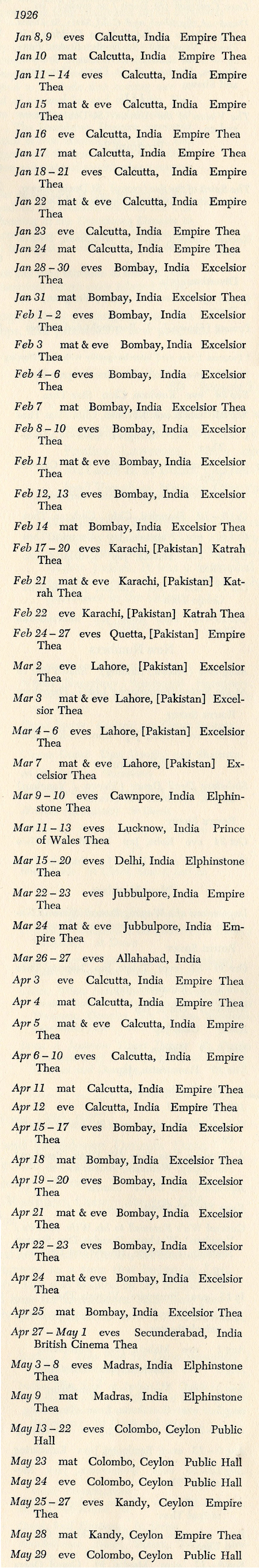

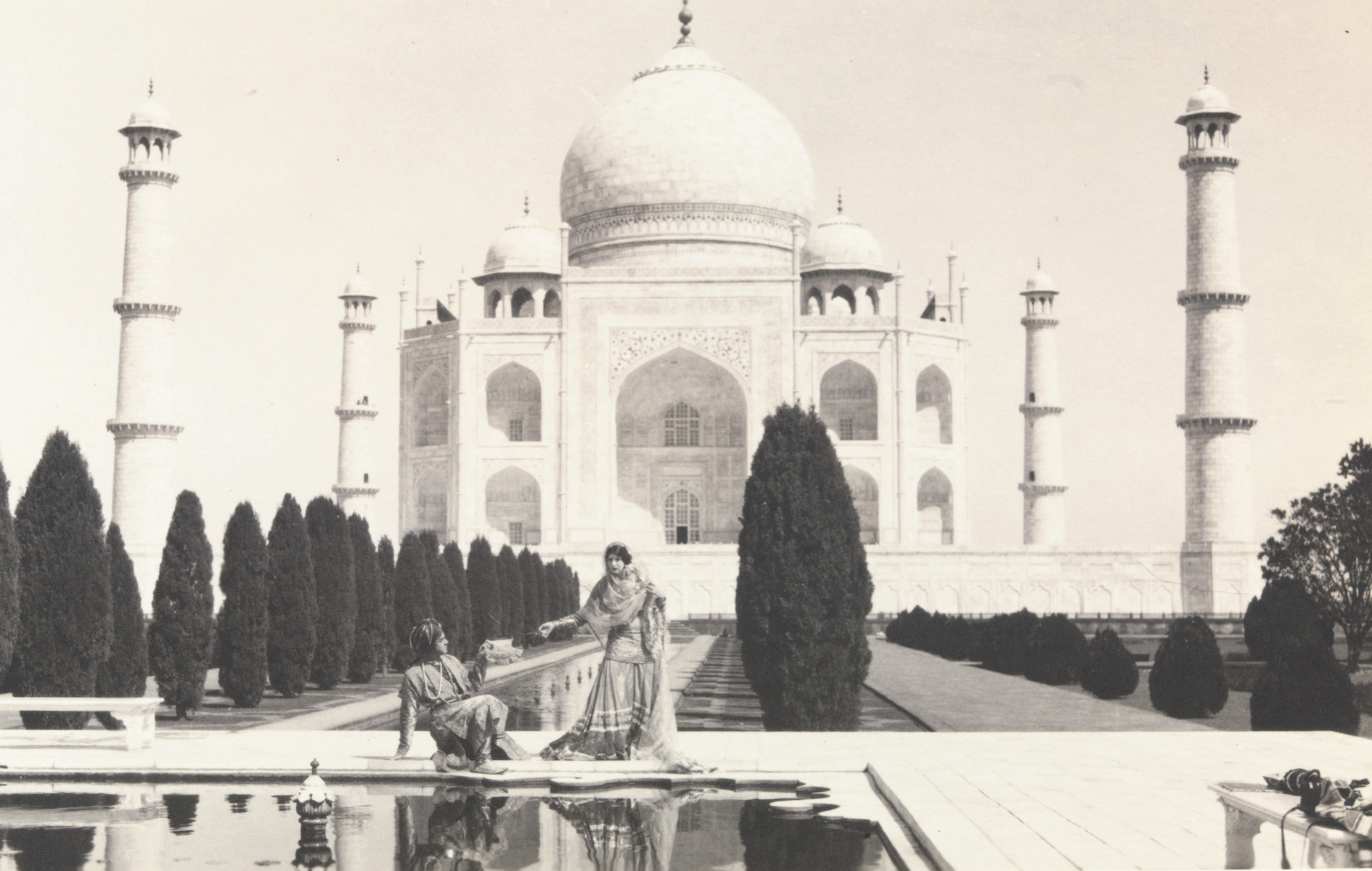

India is arguably the country that would provide the most inspiration to St. Denis and Shawn throughout their careers. The company spent five months in India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka from January to May 1926.

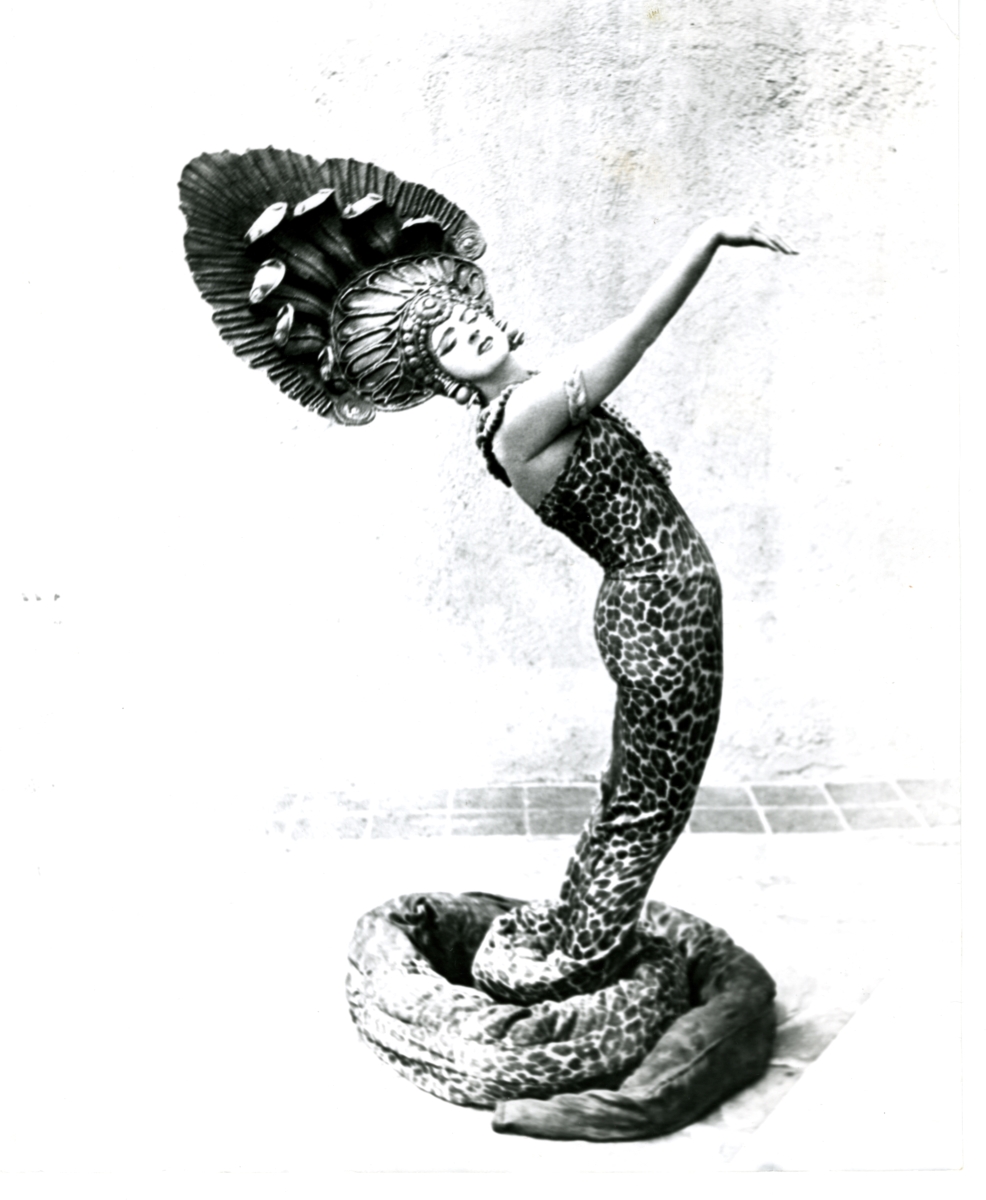

India was one of the earliest influences in St. Denis’s work with the creation of Radha in 1906, twenty years before she would set foot in India. Radha began as an idea for a vaudeville dance inspired by Indian dancers she had seen at Coney Island. St. Denis acknowledged that the resulting work was a pastiche of imagery and fantasy. In her biography she described Radha as ‘a jumble of everything I was aware of in Indian art’ culminating in a Hindu goddess in a Jain temple. To add to this, St. Denis set the solo to a section from the Delibes opera Lakmé. Despite these liberties, or perhaps because of them, Radha made St. Denis a star.

Take a closer look:

While in India, St. Denis was keen to see an authentic nautch dance. St. Denis herself had danced versions of the nautch since 1908 and continue to do so throughout her career. However, colonialism in India had relegated these once heralded court dances to performances by street performers and courtesans. Interestingly, St. Denis’s performances of these dances were enthusiastically received, just as the ballerina Anna Pavlova and her versions of Indian dance had been several years earlier. Jane Sherman later wrote that:

It was hinted at that one of the reasons Indian audiences reacted with such enthusiasm to the Denishawn East Indian dances was because, consciously or subconsciously, they revelled in the spectacle of “white” women abasing themselves to the level of “native” prostitutes. On the other hand, there is little doubt that they also responded to their traditional art as St. Denis revealed it to them.Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance, 36. For further discussion on this see Paul Scolieri, Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019) and Uttara Asha Coorlawala, “Ruth St. Denis and India’s Dance Renaissance”, Dance Chronicle 15, no. 2 (1992):123-52

Take a closer look:

Shawn also created a new Indian inspired work while on tour, this time based on the God Shiva. The resulting solo, The Cosmic Dance of Siva, premiered in Manila at the Grand Opera House with a score by American composer Lily Strickland, who at the time was living in India. This solo was a ‘statue dance’ and similar to Kuan Yin in that it was largely inspired by sculptures and paintings and consisted of slow controlled choreographed movements. Unlike some of the other works created on tour, St. Denis and Shawn continued to perform versions of their Indian works for many years.

In the late autumn of 1926, St. Denis, Shawn and the dancers of Denishawn returned to the USA. Several of the works that they created on the tour were incorporated into a program with the overall title of Gleaning from the Buddha-Field, which included Momiji-Gari, White Jade, General Wu’s Farewell to His Wife, A Javanese Court Dancer, A Burmese Yein Pwe, The Cosmic Dance of Siva, and In the Bunnia Bazaar. This program was included on the 1926-27 USA tour of Denishawn. The more authentic style of these works was not particularly popular with American audiences, and most of them were never performed again after this time.

Postscript from Phil Chan:

Whether or not we agree with the idea that culture can inherently be “owned,” can we at least appreciate the desire of Shawn and St. Denis to shift in a direction of both greater authenticity and greater integrity following their encounters with actual Asian culture? Even by today’s standards, we have to ask ourselves what we actually expect from our artists. Can we fault Shawn and St. Denis for their early forays into Orientalism? Geopolitical intrigue in Asia and a desire to experience other cultures was a commercial demand, and Orientalism had been in vogue since the 17th century in France. In the early 1900s, it took effort and determination for Europeans to gain deep experience with Asian cultures so far away, and both Shawn and St. Denis made that effort.

Unfortunately, their shift toward greater authenticity and cultural respect was not lasting; Western audiences responded far more enthusiastically to their earlier fantasy Oriental works compared to the new Asian ballets developed during and immediately following the Far East Tour. Sadly, in response we see St. Denis shifting back into a fantasy Orientalism later in her career. To this day, I suspect most Western audiences prefer Turandot to Taiwanese Opera, The King and I over Thai Khon dancing, cream cheese wontons over chicken feet. What are the implications for today’s artists who would like to draw from their own heritage but must also take audience preferences into account?

The Denishawn story and the body of works they produced are a cautionary tale, getting at issues that seem quite urgent today. We feel uncomfortable about seeing White dancers dressing up as sacred deities from Asian cultures, taken out of context and turned into entertainment. We have to wonder whether artists can embody themes, experiences, religious and cultural expressions outside of their own. Should performing cultures not our own be avoided? But how limiting and problematic that would be, given our diversity and mixing of heritages! How do we find the balance between giving artists opportunities to promote their own heritage and cultures with integrity, while making room to explore and express themselves in forms outside their own backgrounds? How do we learn from each other, empathize with each other, revel in our shared humanity, if we can’t dance together? But where do we draw the line?

Bibliography and Resources

Chan, Phil. Banishing Orientalism: Dancing Between Exotic and Familiar, Yellow Peril Press, 2023.

Chan, Phil. Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing Between Intention and Impact, Yellow Peril Press, 2020.

Coorlawala, Uttara Asha. “Ruth St. Denis and India’s Dance Renaissance” in Dance Chronicle 15, no. 2 (1992):123-52

“Dance We Must: Another Look” PillowTalk with Patsy Gay, Norton Owen, Lionel Popkin, and Paul Scolieri, moderated by Maura Keefe, 2019.

Edwards, Jennifer. “Culture in Context, As Import, and In Exchange” essay on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive, 2020.

Murphy, Kevin and Caroline Hamilton. Dance We Must: The Art and Costumes of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn 1906-1940, Williams College Museum of Art, 2023.

Owen, Norton. “Ted Shawn, Jacob’s Pillow Founder, In His Own Words” podcast episode on PillowVoices:Dance Through Time, 2020.

Popkin, Lionel . “Orienting Myself: Finding my way through Ruth St. Denis’ archive” in Choreographic Practices, 6 no. 2 (2015).

Scolieri, Paul A. Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Scolieri, Paul A. “Ted Shawn and the Defense of the Male Dancer” essay on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive, 2019.

Sherman, Jane. Soaring: The Diary and Letters of a Denishawn Dancer in the Far East, 1925-1926, Wesleyan University Press, 1976.

Sherman, Jane. The Drama of Denishawn Dance, Wesleyan University Press, 1979.

Skybetter, Sydney. “Ted Talks” essay on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive, 2018.

Srinivasan, Priya. “Archival Her-Stories: St. Denis and the Nachwalis of Coney Island” in Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor, Temple University Press, 2011.

“Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances” PillowTalk with Paul A. Scolieri and Maura Keefe, 2022.