Introduction

Since the founding of Jacob’s Pillow, visiting dance companies have posed for group pictures at the flat slab called the “Pillow Rock.” There are hundreds of such images in the Pillow archives, representing thousands of smiling dancers, administrators, designers, and choreographers over nearly a century, an auspicious marker of the passage of people through the place. The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has been a frequent guest at the Pillow since the 1950s, but for their last visit in 2009, the founder of the company, Merce Cunningham, was notably absent.

His health had deteriorated over the previous weeks, and so the troupe took the trip—and “Pillow Rock” picture—without him. Once the company’s performance run reached an end, they returned to Manhattan in a loose caravan, and as the last of the production team crossed into the city, Cunningham died in his sleep. It was Sunday, July 26th, 2009. He was 90.

Overview of Merce Cunningham’s Career

Cunningham was a giant figure in American modern dance, a preeminent avant gardist who exerted a powerful influence on the fields of performance, film, music, and visual art. Born in Centralia, Washington in 1919, Cunningham joined the Martha Graham Dance Company at the age of 20 and famously originated the character of the Preacher in Graham’s Appalachian Spring, among other roles. As early as the 1940s, Cunningham (and his catalytic collaborator and eventual life partner, John Cage) began experimenting with compositional methods that sought to complicate the relationship between the individual artist and intentional aesthetic expression. This led to a decades-long, convention-warping disintegration of the choreographic process, and the disentangling of the component parts of proscenium dance (music, lights, costumes, bodies, decor) into asynchronous, independently rendered vectors that happened to occur in shared space at showtime.

This is an inversion of the famed Diaghilevian ethos of Gesamtkunstwerk (roughly translated from Wagner and German as “total art work”) where collaborating artists seek aesthetic harmony and to produce specific affects and narrative elements within a piece of art. Not coincidentally, Cunningham saw himself in the Diaghilevian tradition, as an artist who embraced collaboration in particular, sometimes disorienting ways, but with an aesthetic depth of focus on par with the Ballets Russes. One of the means by which Cunningham—alongside Cage—interrogated compositional form was through his use of “chance procedures,” or aleatory choreographic techniques. Cunningham used these methods to momentarily spring outside his own habitus and imagination, harvest non-obvious and potentially impossible movement ideas, and then activate his dancers’ embodied intelligence so as to choreograph. The creative black box and controlled chaos of his dancemaking may have seemed to remove aspects of Cunningham’s agency, but the system was still designed by CunninghamHe told The New York Times in April of 2009, the point of such procedures is to “find out something you didn’t know. It lets your mind open up to something new.” How movements found their way into a dance may have been subject to chance, but the finished product always represented the apotheosis of Cunningham’s choreographic intentions and a vaudevillian sense of showmanship. In this way, much of Cunningham’s career can be understood as proto-digital, as many of his dances anticipate and deploy emergent means of digital production (for example, BIPED and the technology of early motion capture, the subject of another essay in this series). The creative black box and controlled chaos of his dancemaking may have seemed to remove aspects of Cunningham’s agency, but the system was still designed by Cunningham, and the resulting work necessarily included traces of his imprimatur.

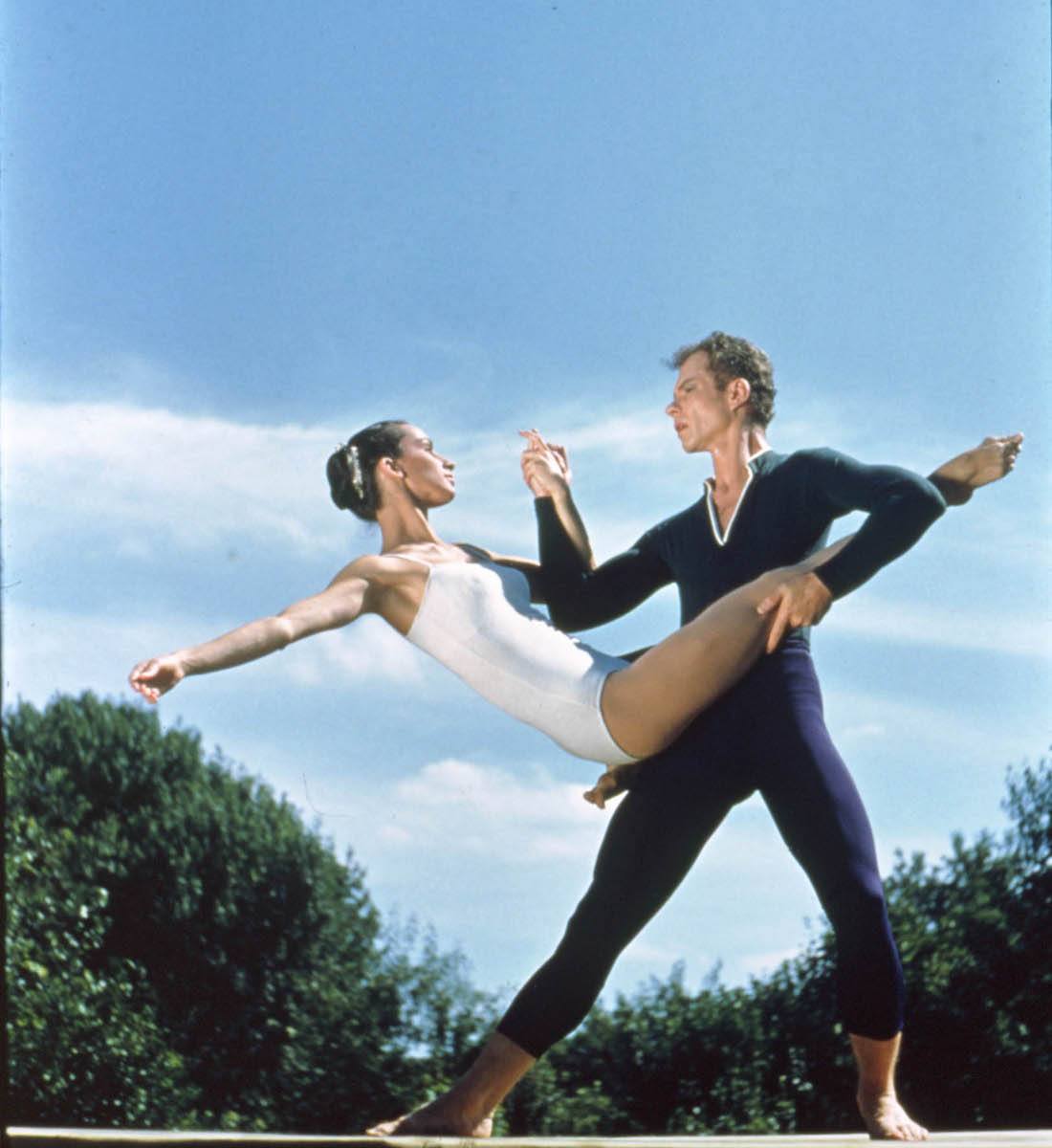

Cunningham was famously cerebral, but he was also, simply, a phenomenal dancer, capable of impossible bounding leaps that defied audience expectations and, seemingly, physics. In early archival footage of his Banjo at the Pillow in 1955, one can see a 36-year old Cunningham executing a stunningly high, modern-dancerly gargouillade (a complex balletic jump where both feet circle towards and away from the opposing knee). With each of these leaps, Cunningham adds an additional “beat” of his foot at the last possible moment, even as he descends perilously low to the ground. This is virtuosic (if, somewhat obscure) movement, executed as only a dancer with brilliant classical technique and preternatural buoyancy could.

Cunningham Ages

Cunningham continued to perform with his company for decades. As Cunningham’s physical container diminished, he adjusted his kinaesthetics. After he lost the ability to balance unaided, he performed with a barre.

After he couldn’t stand, he sat. His physical capacities dwindled, but after all, Cunningham was used to working within shifting parameters.Cunningham did not long for his repertory and company to exist in perpetuity. Cunningham did not long for his repertory and company to exist in perpetuity. A month before he died, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company announced an unprecedented plan for what the institution would do once Cunningham was gone. With rigor, celebratory prose and utterly without remorse, the plan articulated how, when Cunningham passed, the company would tour the world for two years, and then close. The Legacy Plan has since rightfully become a case study for single-artistic director dance companies pondering the departure of a founder.

The End

After the performances of Nearly Ninety (so named because Cunningham was almost 90 years old, and because it lasted almost 90 minutes) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in April of 2009, things started slowing down. Even though there was no public prognosis or estimate for how long he yet had to live, there was a growing sense he had limited time. Small groups of dancers, administrators, collaborators, and alumni visited him to say goodbye. That last week while the company was at Jacob’s Pillow, Stephan Moore (then sound designer and music coordinator for the company, now a Lecturer at Northwestern University) set up a primitive “uStream” live stream of rehearsals and performances from a laptop with the intention of letting Cunningham intermittently watch the company from New York City.

This live stream—the first of its kind at the Pillow—was a high latency, low quality kluge that nonetheless relayed a globe-spanning choreographic project back to its originator, just before his end.

Once Cunningham died, the legacy plan was carried out, and the company toured and disbanded to acclaim. Daniel Madoff, a member of the final incarnation of the Cunningham company, deposited a quota of Cunningham’s ashes at Jacob’s Pillow—at the Pillow Rock.

PUBLISHED September 2019