A New Kind of Tap Troupe

When the Jazz Tap Ensemble first performed at Jacob’s Pillow, in July 1983, the company was in the vanguard of a new phase in the history of tap dancing. Performing at Jacob’s Pillow, in fact, was part of the proof. In the 1950s and ‘60s, tap had gone out of fashion in the entertainment worlds where it had once been ubiquitous: vaudeville, nightclubs, Broadway, Hollywood. But in the late ‘70s, a young generation of dancers—many who had taken tap lessons in their youth but had veered into modern dance in college—were finding ways to bring tap into the realm of concert dance. They were forming modern-dance-style companies. They were creating choreography. And they were getting themselves hired to perform in places like Jacob’s Pillow.

Four years before, when the group was founded in Southern California, it was called the Jazz Tap Percussion Ensemble. The “Jazz Tap” half of the name was a nod to the past. Tap had grown up alongside jazz, and the big bands of Duke Ellington and Count Basie used to tour with at least one tap act; those days were over, but this new group was picking up the lapsed tradition. The “Percussion Ensemble” half flagged a novel concept. The ensemble consisted of three dancers (Lynn Dally, Camden Richman, and Fred Strickler) and three musicians (Paul Arslanian, piano; Tom Dannenberg, electric bass; and Keith Terry, drums), but they conceived of themselves as a collective of musician-dancers. Once, when a journalist praised Richman’s dancing but added, “and the musicians are great,” Richman shot back, “Yeah, well there are six of us.” “Reveille for TAPS” by Maggie Lewis in The Christian Science Monitor, January 3, 1980

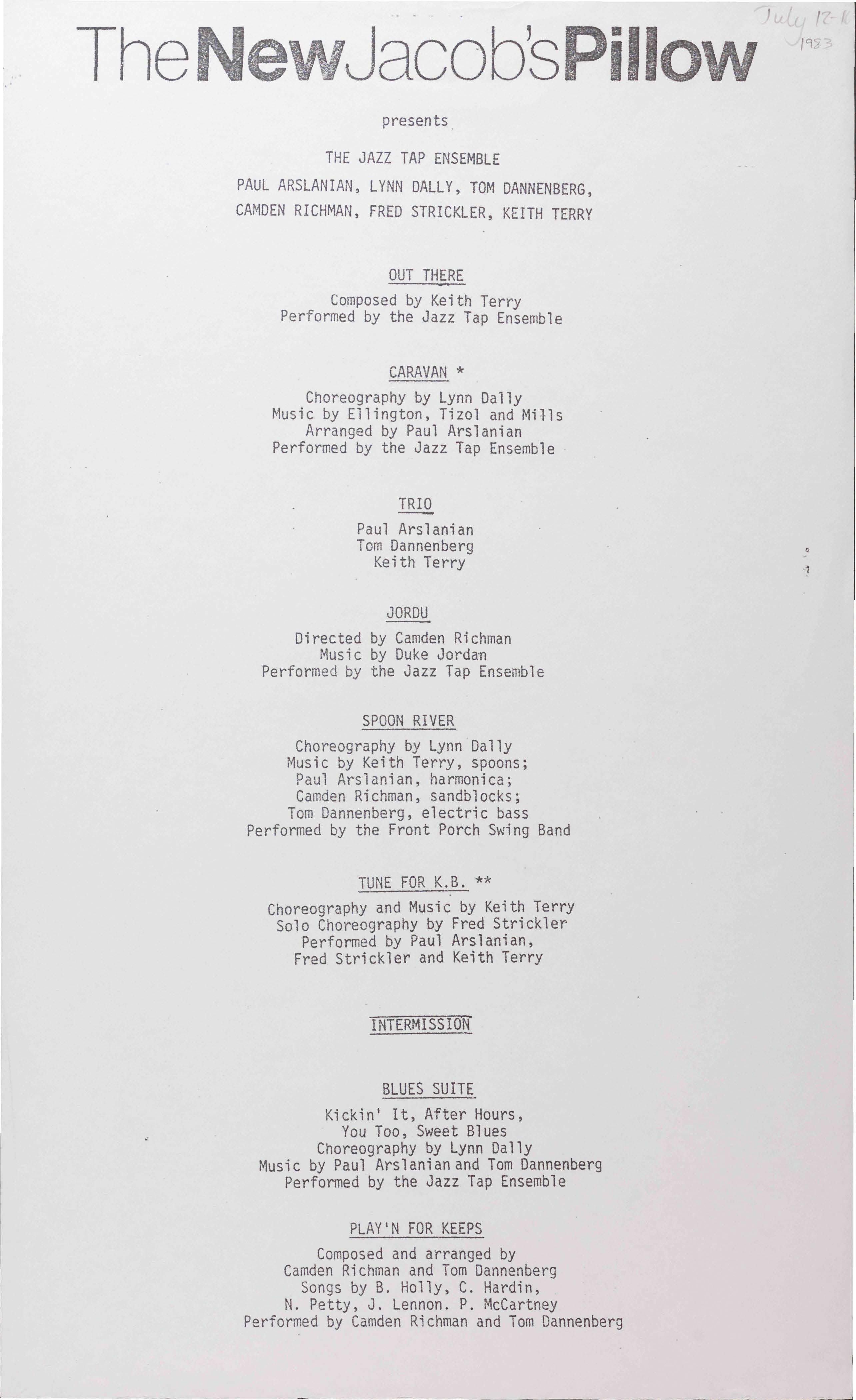

That collective approach was emphasized from the very first moments of the 1983 Pillow program, as all six members entered in a line, all in tap shoes, all tapping and clapping contributions to a complex common rhythm before facing off in rhythmic dialogue, one on one or three against three.

And at the program’s end, everyone danced again, stomping and shuffling out the Shim Sham, a traditional routine from the late 1920s.

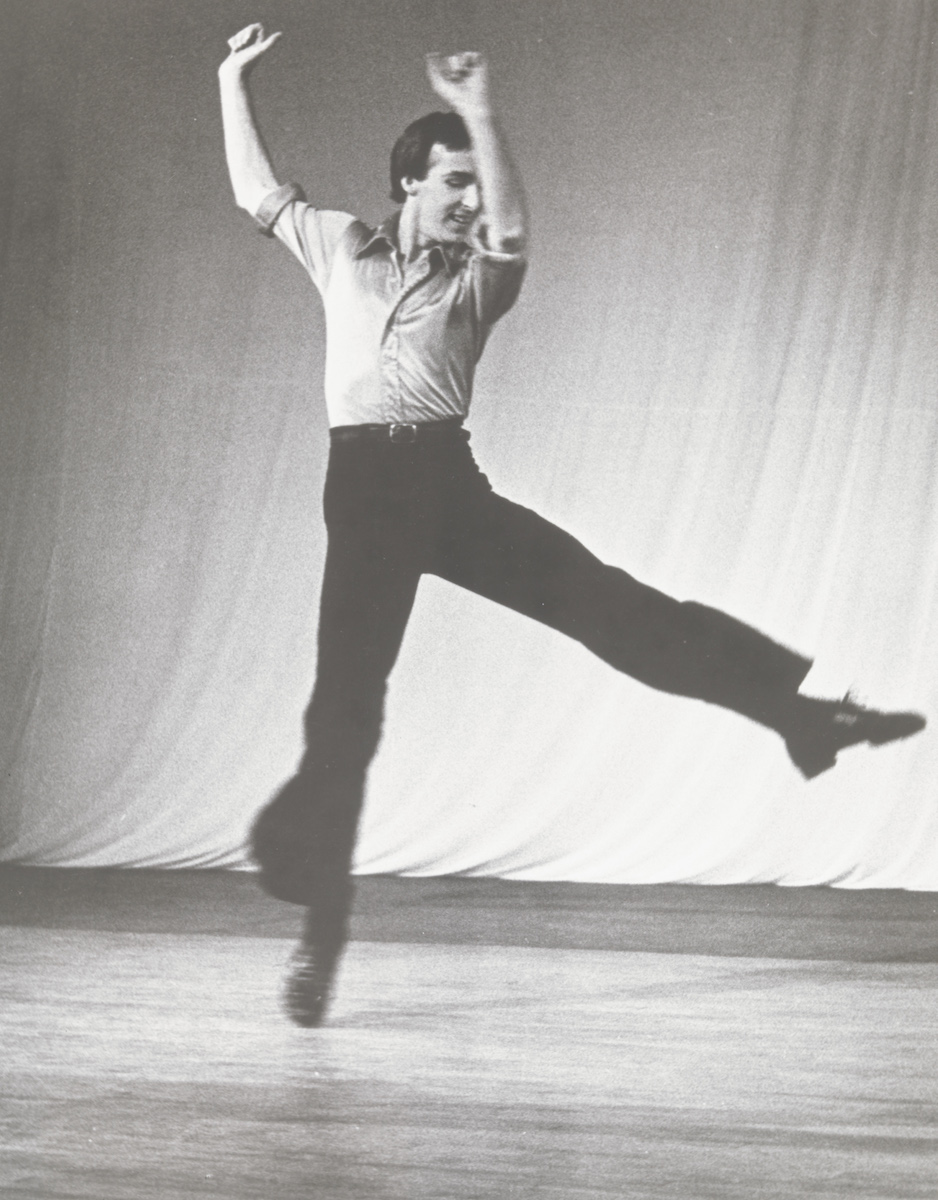

Mixing it up was this group’s M.O. During one number, Arslanian and Terry took center stage to trade rhythms with claps, snaps, sticks, and bells—intricate maneuvers that made the audience laugh in delight—while Strickler ambled in and out, doing hotshot tap tricks. In another, Terry and Richman (below) engaged in a duet of hambone and stomping, at once casually comic and impressively complicated. Even in numbers where the musicians kept to the side with their instruments, they might sneak out in the middle to ambush the dancers with some foot repartee.

Behind all of this role blending was an idea of conversation. From the jazz tradition, Jazz Tap Ensemble took the custom of trading: back-and-forth musical exchanges among the dancers or between the dancers and the musicians, a swapping that was structured in advance but improvised in the moment.

Yet the ensemble augmented those traditional interactions with other kinds, just as their musical selections encompassed not just jazz standards but original compositions, blues, The Beatles, even a hoe-down, complete with harmonica and spoons. The mix struck people as fresh, current. Dancing in flirtatious response to Dannenberg’s New Wave electric bass playing and vocals, Richman was an impudent pixie in legwarmers, a sister to Cindy Lauper. As Maggie Lewis wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, the show was “anything but nostalgic. It was strictly an ‘80s experience.”“Reveille for TAPS” by Maggie Lewis in The Christian Science Monitor, January 3, 1980

Musically, the show was bursting with ideas, and choreographically, too. In the Village Voice, the esteemed critic Deborah Jowitt wrote,

Their ensemble choreography investigates the interplay of unison, antiphony, and counterpoint as fully as any contemporary choreography I’ve seen, and more than most.”

Consider the sly and atmospheric stringing together of solos and duets, of melancholic looseness and ratcheting acceleration, in Dally’s film-noir-ish Blues Suite. Or track the lines and circles woven by the dancers through her Caravan, the sociable interplay of three together or one breaking out as the other two keep each other company.

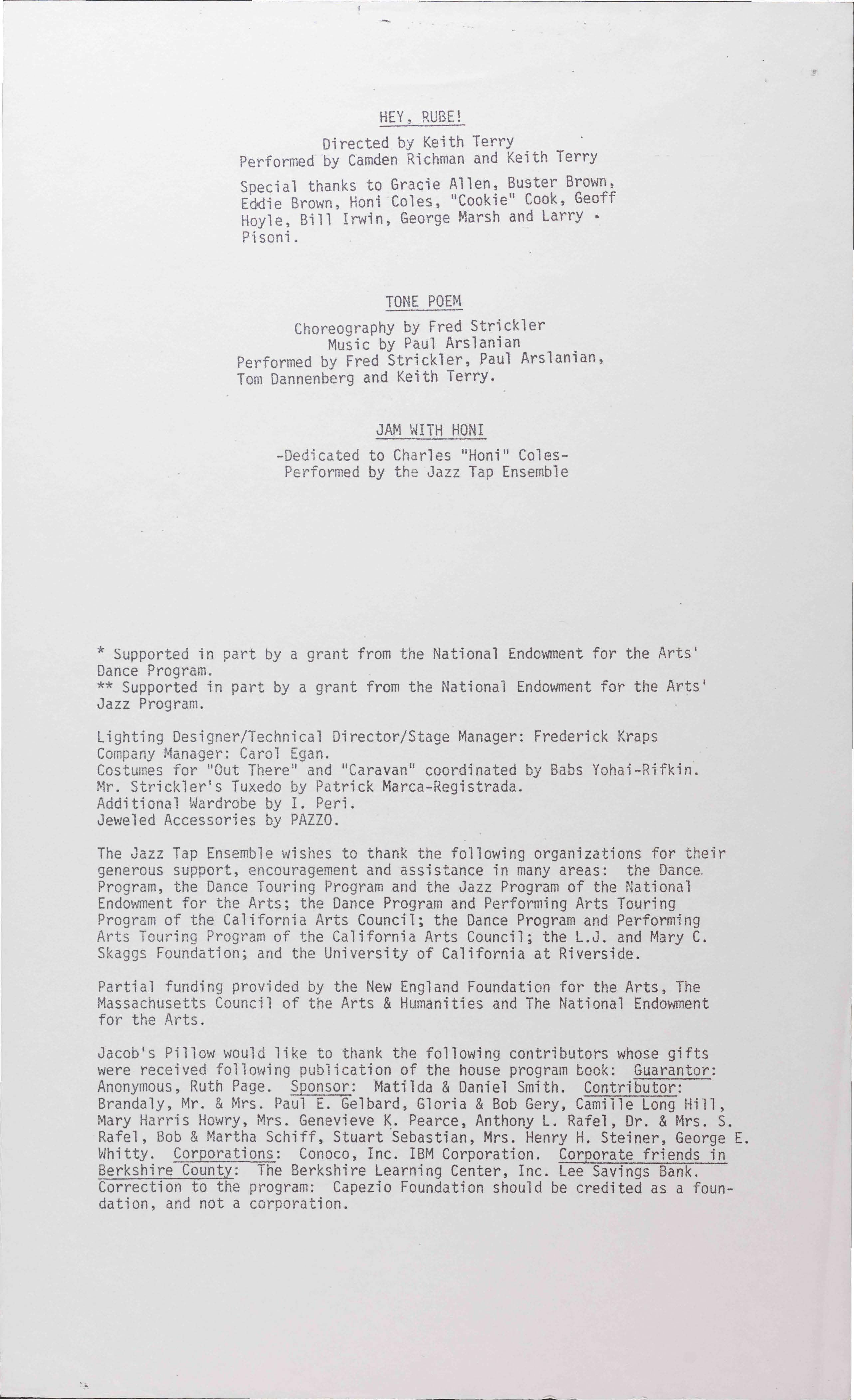

Of the three dancers, Richman had the least modern-dance training.

She had spent a year in the San Francisco troupe of Margaret Jenkins but converted to tap after she saw a rare television appearance by the unsurpassed jazz hoofer Baby Laurence. She never met Laurence, who died in 1974, but she did meet Eddie Brown, an aged master of jazz improvisation and what he called Scientific Rhythm.

She convinced Brown to teach her—going to his place, rousing him out of bed, and picking up what she could as he danced on a piece of wood in the basement. Then she studied with Honi Coles, a long-legged dean of elegance and speed. Much of his style infused hers. In 1976, she formed a jazz trio with Arslanian and Dannenberg.

If Strickler’s showmanship sometimes called to mind a star pupil in a dancing-school recital, that was an accurate reflection of his childhood as a scholarship tap student in the Columbus, Ohio studio of Jimmy Rawlins.

He also took ballet, though he kept that a secret from his friends in high school. But in the early 1960s, tap dancing didn’t seem a viable profession. At Ohio State University, he swerved into modern dance, learning principles of composition. He moved to Southern California and joined the modern-dance troupe of Bella Lewitzky.

It was Dally who brought Richman and Strickler together. She had also been an ace tap student as a child: Jimmy Rawlins was her father. But she, too, had put away her tap shoes at Ohio State University, studying the techniques of Martha Graham, José Limón, and Merce Cunningham. In the mid ‘70s, she moved to Los Angeles to teach and to start a modern-dance company. Soon, though, responding to a rising nostalgic interest in tap, she began introducing barefoot tap pieces into her concerts and teaching tap classes. Richman was a student. Strickler was an old friend, and after they opened a studio together, they started practicing tap, remembering it. They decided to put on a show. People liked it, and so, joining with Richman’s trio, they formed a company.

New Blood

By 1985, Dally was the only original company member left. It was she who kept the troupe going, bringing in a new musical director—the drummer Jerry Kalaf—and a steady turnover of dancers. Of the new hoofers, the most long-serving was the virtuosic Sam Weber. When JTE next visited the Pillow, in 1993, Weber was clearly its star. Watch and listen to the whirlpool of variegated tones with which he began Oleo (below), a quiet thunder in the feet that sets his loose fabric on the rest of his body ashimmer. Then keep paying attention as he states the melody and trades phrases with Kalaf: the rhythmic invention, the ease of execution. This is jazz tap of a very high order.

This 1993 show also exhibited the fruit of Dally’s Caravan Project, an effort to recruit and train young tap dancers, especially young African-Americans, a group that had not been represented much in the ranks of Jazz Tap Ensemble and similar troupes. In the 1993 footage, Dormeshia Sumbry and Derick K. Grant, teenagers of enormous talent and skill, looked unfinished only in comparison with their future selves, the mature artists who would appear at the Pillow twenty years later.

Performing with Jazz Tap Ensemble, these leaders of the future (and more who followed in their footsteps) learned about spatial composition and interacting with a band. They became versed in the styles of such predecessors as Eddie Brown, whose patterns and rhythmic proclivities formed the substance of Doxy. They learned how to glide through the super-slow 1940s soft shoe of Honi Coles and Cholly Atkins or a 1930s solo by Bill Robinson. Weber also danced film numbers by one of his idols, Fred Astaire. With such historical re-creations, Jazz Tap Ensemble exhibited its connections to the history it extended.

With the Masters

It had also been a company tradition, from the beginning, to invite living masters as guest artists, links in the person-to-person transmission of the art. In 1998, when Dally and Weber came to the Pillow with some more gifted recruits, they brought a Boston master who already had a relationship with the Pillow: the great Jimmy Slyde. He had injured an arm but, as he said, his “feet were still working,” so he danced a few songs anyway, working his usual slippery magic alone with the band.

To see and hear Interplay after seeing and hearing Jimmy Slyde was one of the best ways to understand how Jazz Tap Ensemble was preserving jazz tap at the end of the twentieth century.Then the company performed Interplay, a 1995 suite that packaged some of Slyde’s steps and approaches as piquant choreography and prompts for improvisation. It was one of the company’s most successful efforts in making the transitions between set and free as seamless as possible. Introducing it, Weber remarked that normally when troupe performed it, he had to inform the audience about Slyde, “the most ripped-off dancer in tap.” This time, though, the audience experienced Slyde first, and in the light of the original, each dancer’s variations shone all the brighter for being close to the source. To see and hear Interplay after seeing and hearing Slyde was one of the best ways to understand how Jazz Tap Ensemble was preserving jazz tap at the end of the twentieth century.

(The structural finesse of Interplay is difficult to isolate in a short clip, but here watch how a group section transitions into a duet into a solo, improvisation and choreography bleeding together, as different bodies and aesthetic sensibilities reflect aspects of Slyde differently.)

The 71-year-old Slyde wasn’t the only guest in 1998. There was also Dianne Walker, who wasn’t one of the old masters. In her late forties, she was closer in age to Dally and Weber, having started her professional career around the same time that Jazz Tap Ensemble was founded. She joined the group for the Eddie Brown piece Doxy, and in a set of improvised solos (different every night) revealed herself as a distinguished stylist, softly and subtly able to hold her own on a program with Slyde or with Weber’s tour-de-force All the Things You Are (below). By including Walker among the likes of Slyde and such previous guest artists as Honi Coles and the Nicholas Brothers, Jazz Tap Ensemble honored her. In a post-performance discussion, she gave the company a compliment in turn. “I’m not in a company because I’m married with children,” she said. “But if I were in a company, I would be in this one.”

Walker could fit into a Jazz Tap Ensemble program, along with the bebop mastery of Jimmy Slyde, the concert-musician virtuosity of Sam Weber, the latest choreographic weavings of Lynn Dally, some repertory pieces whose original cast members were no longer around, a recreation of a Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell movie routine, and the impressive improvisations of promising young talents. Jazz Tap Ensemble could put all of that onstage: a kind of tap ensemble and a kind of a show that hadn’t existed before.

PUBLISHED August 2017