Introduction

When Sam Weber was a teenager, he imagined that he might become a professional tap dancer. It wasn’t such a crazy idea. He had the love for tap. He had the talent and the skills. But in the 1960s, the world didn’t seem interested in tap anymore. It took a few decades for his dream to be realized.

By the time he first appeared at Jacob’s Pillow, with Jazz Tap Ensemble in 1993, he was 43 and obviously a fully formed virtuoso. Watch and listen (below) just to how he starts his solo dance to “Oleo.” The speed is amazing, but more amazing is the clarity maintained at such high velocities, the separation of each note from the others, and more amazing still is the tonal variety and rhythmic detail within the rush. So little motion for such a profusion of sounds, so little apparent effort for such thunder. And then another kind of music follows as he states the melody of the Sonny Rollins tune and trades phrases with the drummer. This mild-mannered fellow is an ace jazz musician, one of the greatest tap dancers of his day.

Finding a Niche

Weber’s introduction to tap wasn’t very promising: “I remember this woman who was English, yelling ‘Stamp! Stamp!’ I hated it.” He was three years old. But his parents took him to other teachers and found a good one, a former vaudevillian with a relaxed style who opened Weber’s young ears to rhythm and seeded his love for tap.

When Weber was ten, his family moved to San Francisco, which turned out to be an excellent piece of luck, since the change of address and an ad in the yellow pages brought him to the studio of Stan Kahn. Here was a great teacher, a man with an analytical mind capable of zeroing in on essential mechanics and principles, an educator with a system that worked. Some of the exercises were written on a blackboard in Kahnotation, a language that Khan had devised for notating tap. Weber’s mind and technique developed on strong scaffolding.

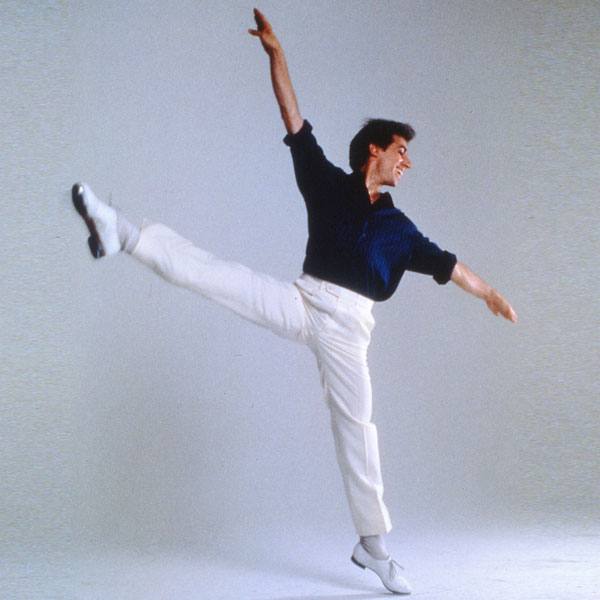

Before Weber had taken a ballet class, people would tell him that he must have taken a lot of ballet classes. That’s what Kahn’s style looked like: disciplined, weight forward over the balls of the feet, torso lifted. Another teacher at the Kahn studios—Rodney Strong, who became famous for his California winery—taught some of the technique of Paul Draper, who had incorporated ballet into his tap in the 1930s and ‘40s, tapping to classical music in swank nightclubs and concert halls. “I always liked that hovering-over-the-floor feeling,” Weber recalled.

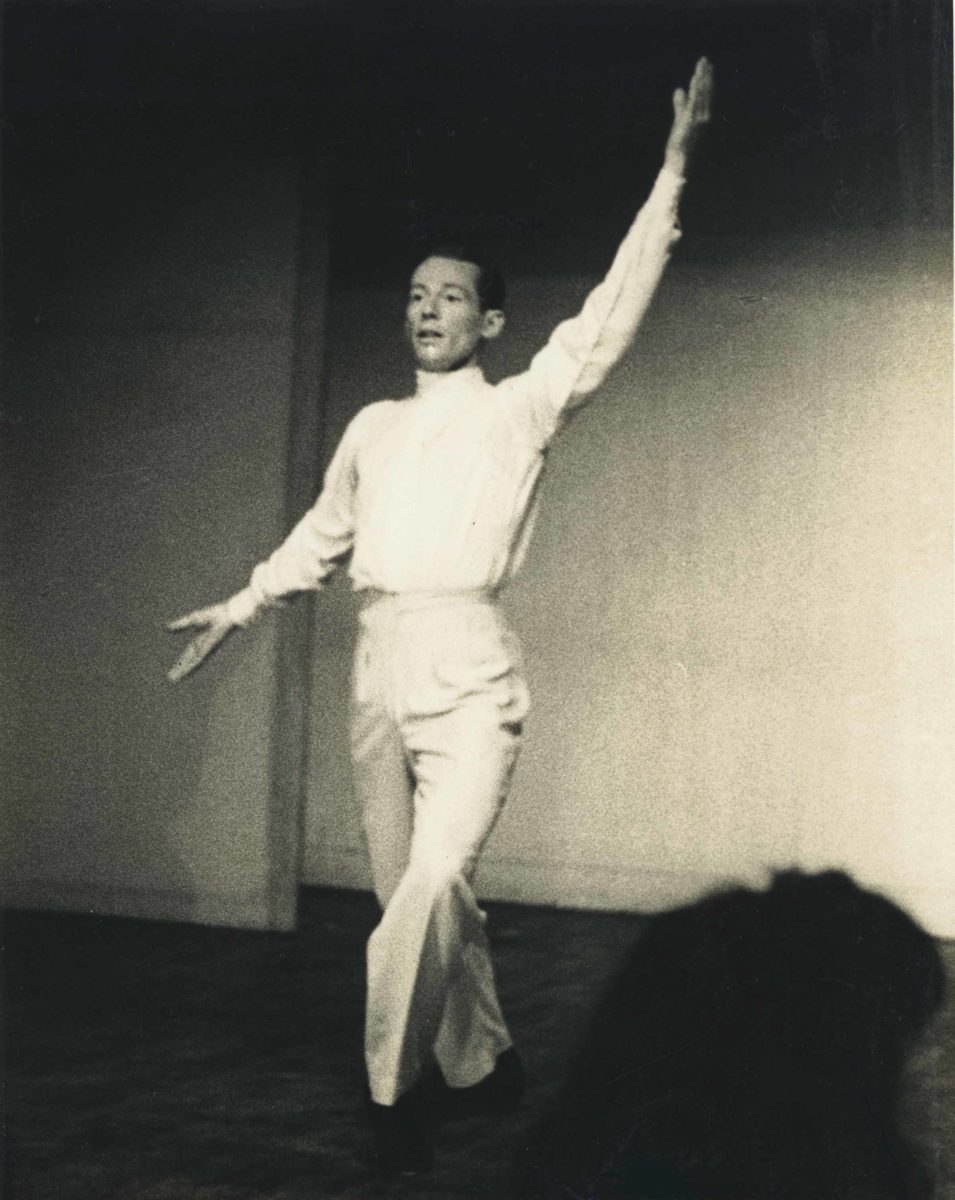

But Kahn did later insist that Weber study ballet. He hated it at first, though he grew to like it. And as he grew into adulthood, and the demand for concert tap dancers seemed close to nil, he took more and more ballet, including a year at Juilliard. He danced with the Joffrey Ballet’s second company and San Francisco Ballet. He was a founding member of Peninsula Ballet Theater in San Mateo. Over the years, he kept up his tap on the side, still studying with Kahn, periodically performing Morton Gould’s Tap Dance Concerto (a 1952 score for a tap dance soloist) in pops concerts with symphony orchestras. But as he entered his mid-thirties, now a principal dancer with the Sacramento Ballet, he began to consider retiring, as ballet dancers often do at that age. Instead, a second dancing career opened up.

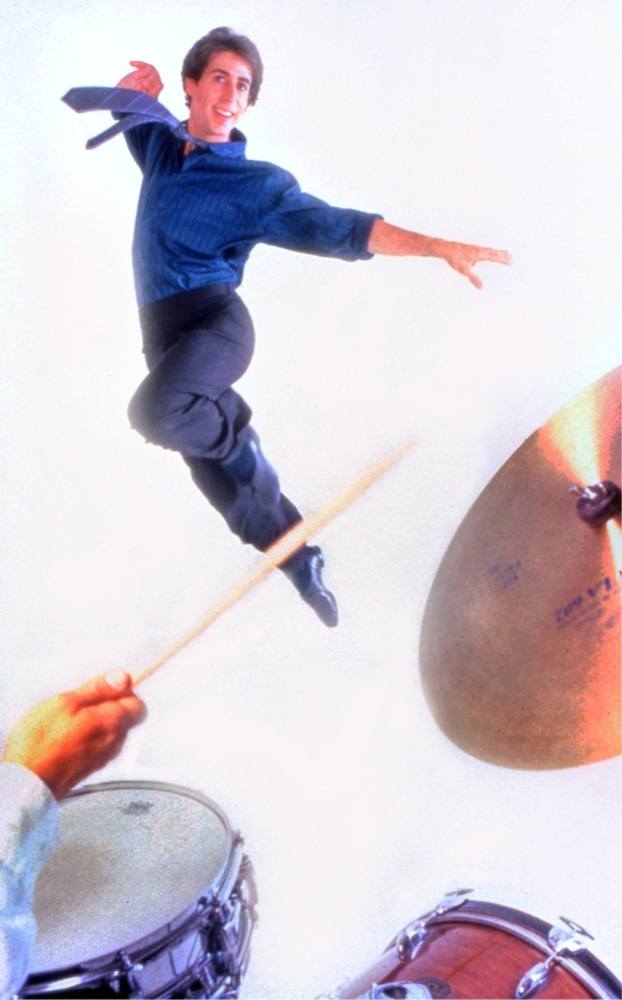

The Jazz Tap Ensemble had been founded in 1979. It was a trailblazing organization, taking up the tradition of tap dancers (such as Honi Coles and Jimmy Slyde) who had performed with jazz big bands and transferring it to the repertory format and concert venues of modern dance. Half of the company members were musicians and half were dancers, but they all considered themselves musicians, alternating between set compositions and jazz improvisation. When Weber first saw the ensemble perform, he thought, “They’re doing what I always wanted to do.” But there didn’t seem to be a slot for him, not until 1985, when one of the dancers, Fred Strickler, left the group. Weber auditioned and was accepted. After his years of ballet, dancing with Jazz Tap Ensemble was “like coming back to something that really felt comfortable,” Weber remembered. “It was like finding your true calling.”

With JTE, Weber tapped to Bach as well as to jazz. If his balletic carriage tended to be the first thing that people noticed about him, it was his virtuosity that people remembered. He continued to learn—in the classes of such veterans as Coles, Eddie Brown, and Steve Condos and alongside them onstage. He earned a reputation for reconstructing classic movie routines, particularly those of Fred Astaire, and this knowledge also fed into his style. He became a master teacher himself, one whose rigorous, specialized system (based in Kahn technique) often frustrated advanced dancers with more intuitive training. Michelle Dorrance, a leader in tap today, remembered fearing his classes when she was an already accomplished teenager: “It made you feel like you couldn’t dance. It was like learning to speak again.” The frustration was productive, though. “I’m clean and fast partly because of him,” Dorrance said. You can see Weber’s influence in many members of Dorrance’s company.

“No one can touch what he does technically,” Dorrance also said, expressing an awed respect for Weber that is common among dancers of her generation. Younger and older dancers share the feeling. At a PillowTalk in 1998, the septuagenarian tap legend Cholly Atkins called Weber one of his favorites, “one of the finest in the tap field;” the great Jimmy Slyde agreed.

It sometimes sounds as if he’s dancing to Bach even when he’s not—his footwork is that intricate, that solid.”

And other critics praised his brilliance—“the equivalent of a virtuoso pianist,” in the words of Anna Kisselgoff in The New York Times.“Jazzy Tapping On Camera and Onstage” by Anna Kisselgoff in The New York Times, February 20, 1997 In 1993, Weber won a Bessie Award, an honor from the New York dance world that no other tap dancer had yet received.

At the Pillow

The first time that Weber came to the Pillow, for a Jazz Tap Ensemble run in 1993, his solos were Oleo and Ariel, a song written by JTE’s musical director, Jerry Kalaf, in honor of Weber’s spirit-of-the-air qualities. Weber also wielded a cane for a bit of Fred Astaire’s “Top Hat, White Tie, and Tails.”

When he returned to the Pillow in 1998, he brought another Astaire piece (the Eleanor Powell duet “Begin the Beguine”), but the tour-de-force was his solo to “All the Things You Are.” The song was arranged to display Weber’s different sides. Starting the Jerome Kern song with the misterioso introduction standard since bebop musicians added it in the 1940s, the musicians then recast the composition as if it were Baroque; from there, they broke loose into swing but returned to the musical wigs and ruffles for a courtly finish.

This oscillation between classical and swing was a tactic that that the tap dancer Leon Collins had used in his 1983 Pillow appearance, segueing from Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee” into Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine.” Weber, in his Pillow performance, flashes more of his ballet background in the Baroque sections: pirouettes, feet pressing through the floor into jumps, heels raised in relevé, crisp and clipped rhythms. The hovering-over-the-floor effect is on high, as is the extreme efficiency of motion that makes you wonder where all the sounds can be coming from.

The swing section, though, makes clear that this former ballet dancer is also a jazz hoofer. What’s unique about Weber, in fact, is how smoothly he incorporates steps and styles borrowed from such jazz hoofers as Steve Condos and Jimmy Slyde into his more balletic base. It isn’t the awkward grafting of most ballet-tap mixes. It’s a true expansion of tap in the direction of ballet, drawing upon ballet’s line and logic and use of stage space without getting too stiff or flimsy and without sacrificing sonic richness.

About two minutes in, the arrangement hits a break and the band goes quiet for a Weber signature step in which, advancing forward, his shoes sound as though there were novelty-toy chattering teeth attached to their soles and going crazy. That’s his technique at its most can’t-believe-your-ears. There’s something superhuman about such rapidity, something mechanical, yet Weber nicely counters that impression with graceful turns, circling the stage in a visual corollary to what his taps are doing with the music. It’s the sound and image of a man doing what he was meant to do.

PUBLISHED March 2017