Introduction

Since the 1940s, Indian dance at the Pillow has been performed by some of the leading artists from India and the west. The first appearances of Indian dance at the Pillow were in the 1940s by Ted Shawn, Ruth St Denis, and La Meri. These iconic artists were inspired by their own perceptions of Indian dance and performed their creative impressions of it, which resulted in several works such as Radha (1906), Incense (1906), and Cosmic Dance of Siva (1929). These works heralded a new beginning for transnational incarnations of Indian dance which would later take on a more sophisticated design at the Pillow. La Meri performed at the Pillow from 1940 until 1972. She first taught her choreography of what was called “Hindu Dance” at the Pillow in 1942. Ted Shawn performed Cosmic Dance of Siva at the Pillow in 1942 and Ruth St. Denis performed Dance of the Red and Gold Sari several times from 1942 to 1956.

There have been several dancers from India, UK, France, Canada and the USA who have performed at the Pillow. This article focuses on the non-hereditary Bharatanatyam dancers and choreographers who have performed at the Pillow since the 1950s. Prior to the 1980s, many of these performances were unfortunately not recorded. Fortunately, the Pillow Archives contain program notes and photographs that provide us windows onto the dances they performed. This essay uses these archival notes as resources to chart out the wide-ranging and multiple forms of Bhararatanatyam-inspired work performed at the Pillow.

Beginnings

Bharatanatyam was originally performed by hereditary dancers from the courtesan community (sometimes referred to as devadasi). T. Balasaraswati (1918-1984) and Lakshmi Knight (1943–2001), two women artists who represented such a heritage, performed at the Pillow in 1962 and 1997 respectively. By the end of the nineteenth century, as colonial modernity gave rise to emergent forms of cultural nationalism, a movement to outlaw the dance practices of hereditary dancers came into being. By the first three decades of the twentieth century, a number of legal interventions criminalized the culture of the hereditary dancers, led not by the British, but by Indian nationalist elites. At the same time, a movement to “rescue” the dance of the the hereditary dance community by inscribing it onto the bodies of upper-caste and upper-class urban women was also brewing in the public sphere. In the process of making it “respectable” enough for non-hereditary dancing women to perform, it had to be purged of much of its content and its overall relation to hereditary dancing communities.

This task was accomplished by a number of upper caste elites in the 1930s and 1940s, and by this time the dance had become institutionalized within a completely new moral and pedagogic framework in the city of Madras. It became a prominent mark of middle-class identity in urban India, and also was deployed as a symbol of India’s civilizational accomplishments. Recent scholarship has traced the ways in which elite nationalist reformers re-invented the arts along the intertwined axes of cultural nationalism, caste politics, and new politicized forms of Hinduism. This article features several members from this new middle class community who have performed at the Pillow.

First Steps at the Pillow

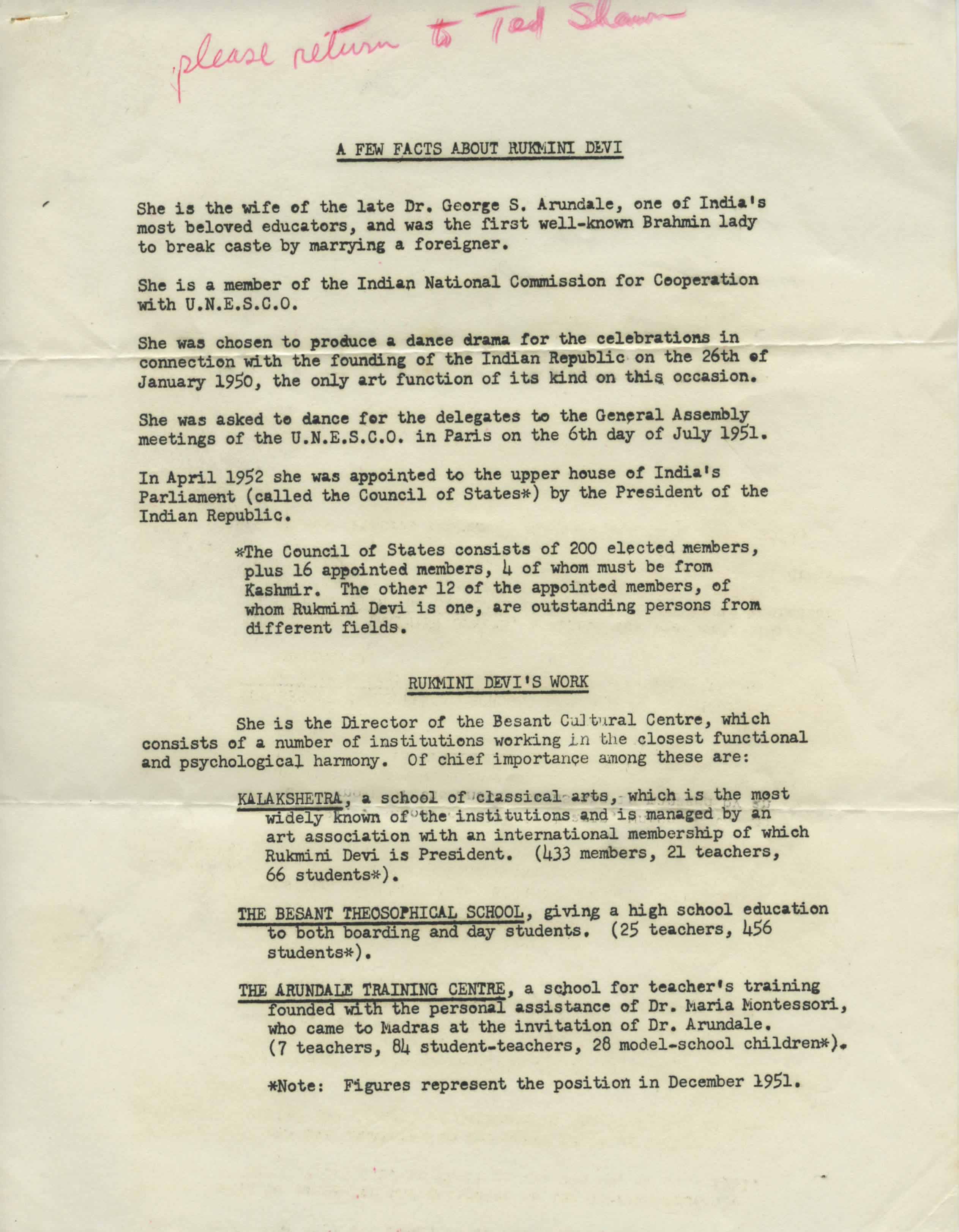

The first Bharatanatyam dancer to lecture at the Pillow was the very founder of this neo-classical style of Bharatanatyam, Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904-1986), who spoke at the Pillow in 1952 (and again later in 1960), and her talk was entitled “Philosophy of the Dance of India.” Arundale was instrumental in creating a new “hybrid” form of Bharatanatyam based on the occult teachings of the Theosophical Society, her own study with dance masters from the hereditary dance community, her brief tryst with ballet, and her own class and caste sensibilities. In her vision, Indian dance was to be seen as a “spiritual experience,” an interpretation that took the dance away from its social history in the hereditary dance community and made it into a symbol of Indian “national culture.” Arundale’s interpretation become extremely popular owing to the forces of India’s cultural nationalism, and it was this philosophical and aesthetic understanding of Bharatanatyam that began to circulate globally after the 1940s.

Ram Gopal

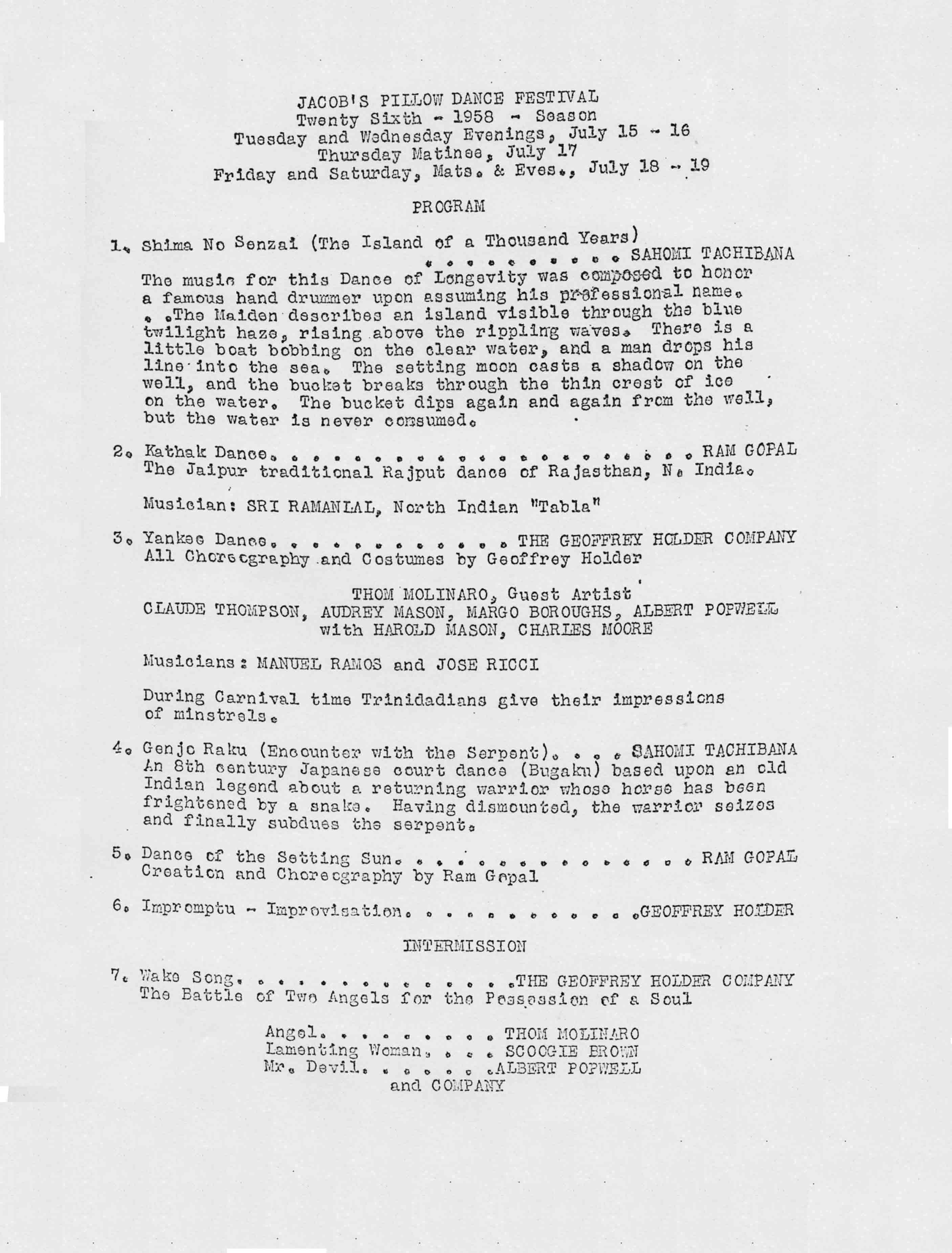

Ram Gopal (1912-2003), one of the first “star” male dancers from India, performed at the Pillow in 1954 and 1958.

He was trained in Bharatanatyam by the hereditary nattuvanars (dance masters) Meenakshisundaram Pillai and Muthukumara Pillai. He also trained in other Indian classical dance styles such as Kathakali, Kathak and Manipuri. In addition to the classical repertoire he learned from his teachers, Ram Gopal performed his own choreographic works informed by Indian painting and medieval iconography. At the Pillow, he performed a variety of solo dances in 1954 and 1958 as part of mixed bills with other companies and artists. Some of the Bharatanatyam-derived pieces Ram Gopal performed at the Pillow included Tillana, Bharata Natya Sastra, Invocation and Siva (which was possibly the popular piece Natanam Adinar (“Siva Danced”), which was one of his teacher Meenakshisudaram’s signature new choreographies for male dancers. He also performed a set of more hybrid, abstract choreographies such as Garuda, Nritya Karana and Dance of the Setting Sun. It must be noted that through Ram Gopal’s work, Pillow audiences saw the changing aesthetic of Indian classical dance following the post-1930s reinvention at the hands of Rukmini Arundale and other nationalist elites. Ram Gopal presented his dance in a “neo-classical” idiom, and Indian dance at the Pillow continues to be represented through these very modern incarnations of what is generally glossed as “Indian classical dance.”

Shanta Rao

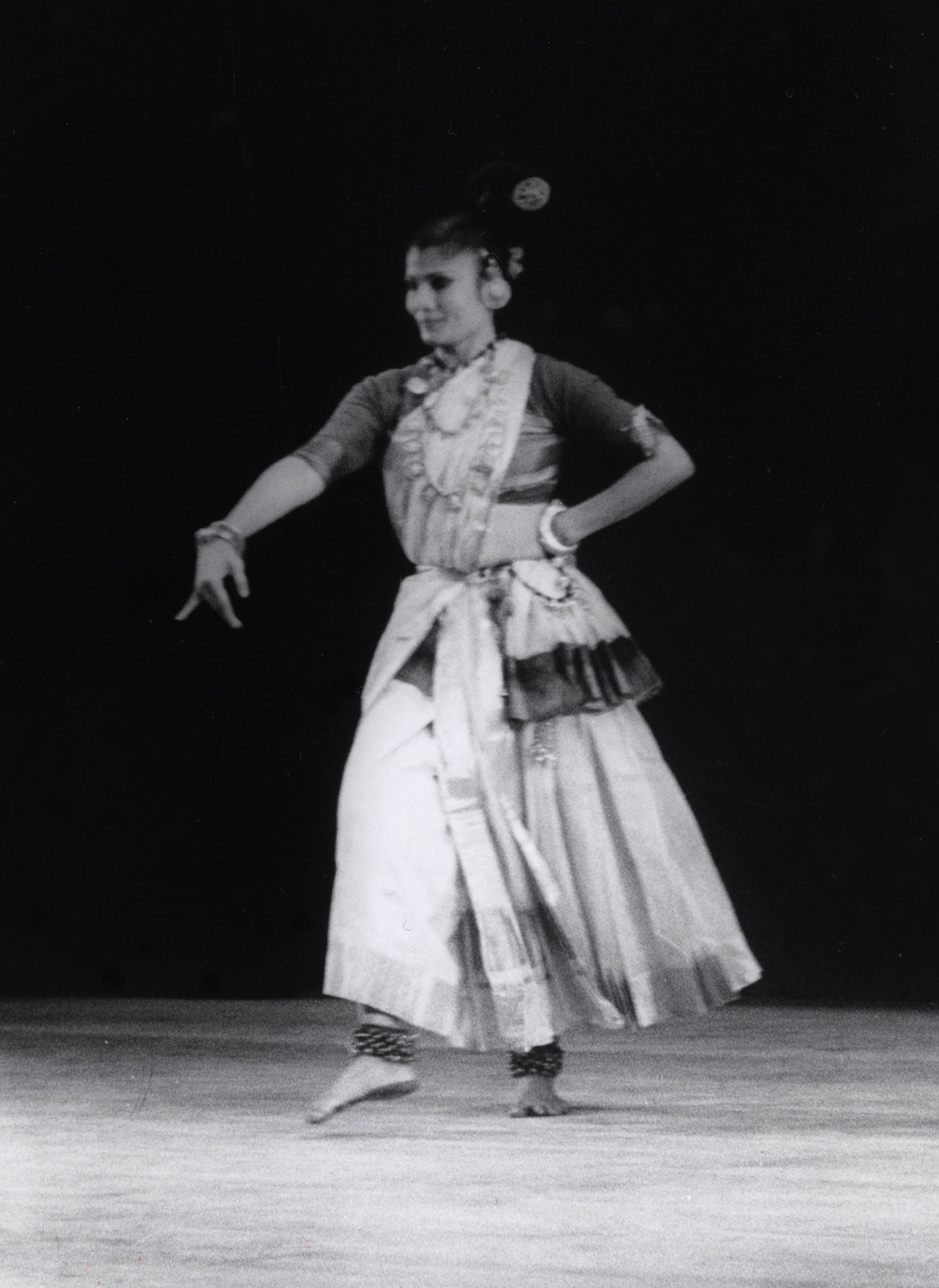

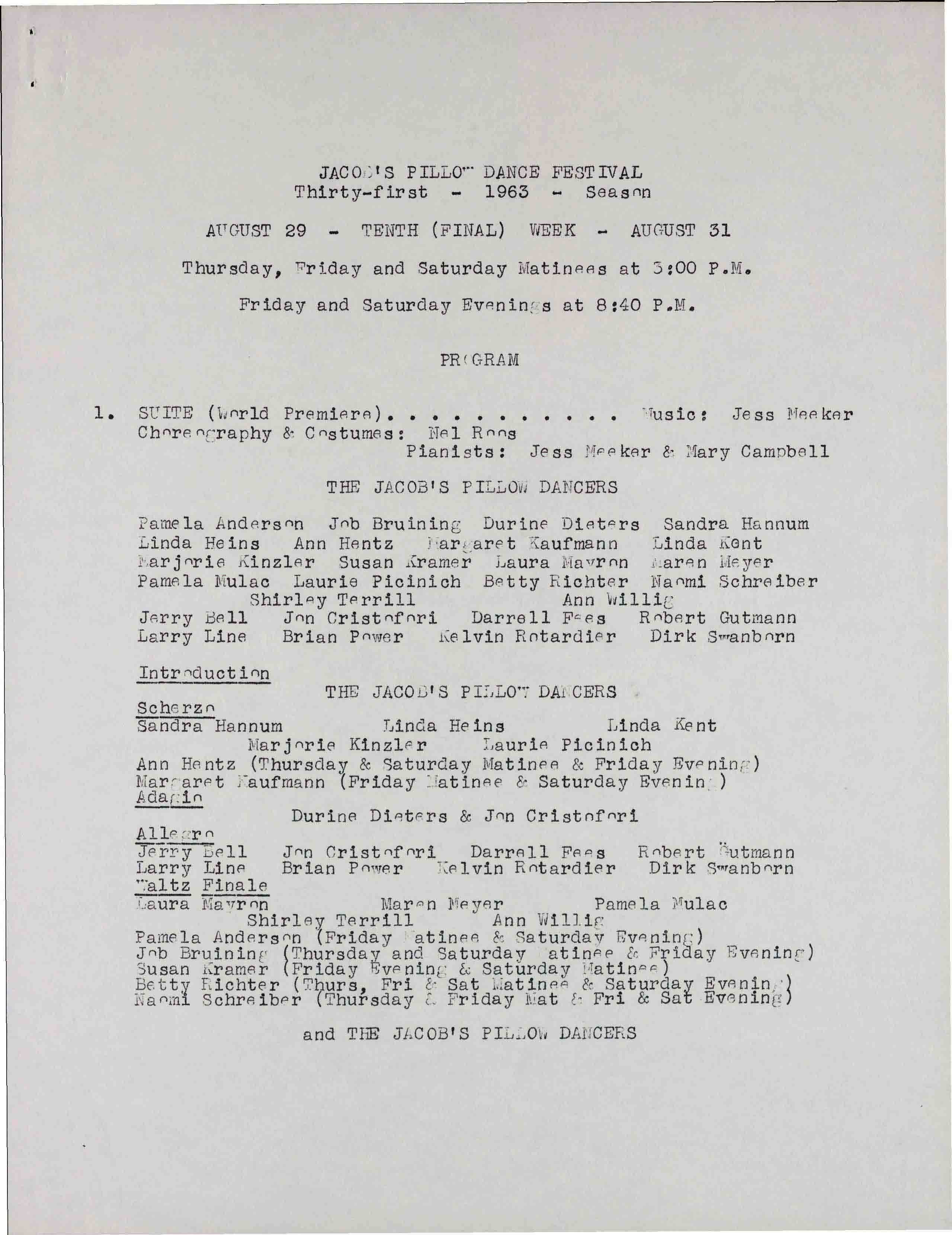

Shanta Rao (1930-2007) is another iconic Bharatanatyam dancer who performed at the Pillow in 1963 with her team of musicians and dancers.

Like Ram Gopal, she too was trained by the hereditary nattuvanar Meenakshisundaram Pillai, and was known for her hyper-athletic yet stunningly beautiful Bharatanatyam technique. In addition to Bharatanatyam, Shanta Rao also trained in other Indian classical dance styles including Kathakali, Mohini Attam, and a dance tradition from Andhra Pradesh which she invented and referred to as “Bhama Sutram.” In order to introduce a sampling of Indian dances to the Pillow audiences, Shanta Rao, like Ram Gopal and Indian dance artists after her, offered a mélange of pieces that we could divide into three genres: Bharatanatyam, Mohini Attam and Bhama Sutram, emblematic of her artistic arsenal. Her Bharatanatyam pieces included non-traditional dance pieces which were originally composed for use in South Indian music concerts, such as the Tana-Varnam and the Pancharatna Kriti. The presence of this type of experimentation at the Pillow reflects the kinds of innovations that were taking place contemporaneously in India.

Indrani

Indrani Rahman (1930-1999) was another important dancer who performed at the Pillow.

She was the daughter of Ragini Devi, an American woman originally named Esther Sherman (1893-1982) who became one of the first performers of Indian dance in America. Indrani was a superb performer herself, and also groomed several dancers in the USA including her daughter, Sukanya. Having trained with hereditary teachers such as Chockalingam Pillai (Meenakashisundaram Pillai’s son-in-law), Indrani was also trained in other classical dance styles such Kuchipudi and Odissi that were just beginning to emerge as “neo-classical dance traditions” in India in the early 1950s. Indrani was one of the main pioneers of the popularization of Indian dance in the USA, and taught extensively throughout the country, including at Juilliard. At the Pillow, she performed a variety of solo pieces and duets with her daughter including Bharatanatyam repertory pieces such as Tillana, in addition to Kuchipudi pieces such as Manduka Shabdam and Bhama Kalapam.

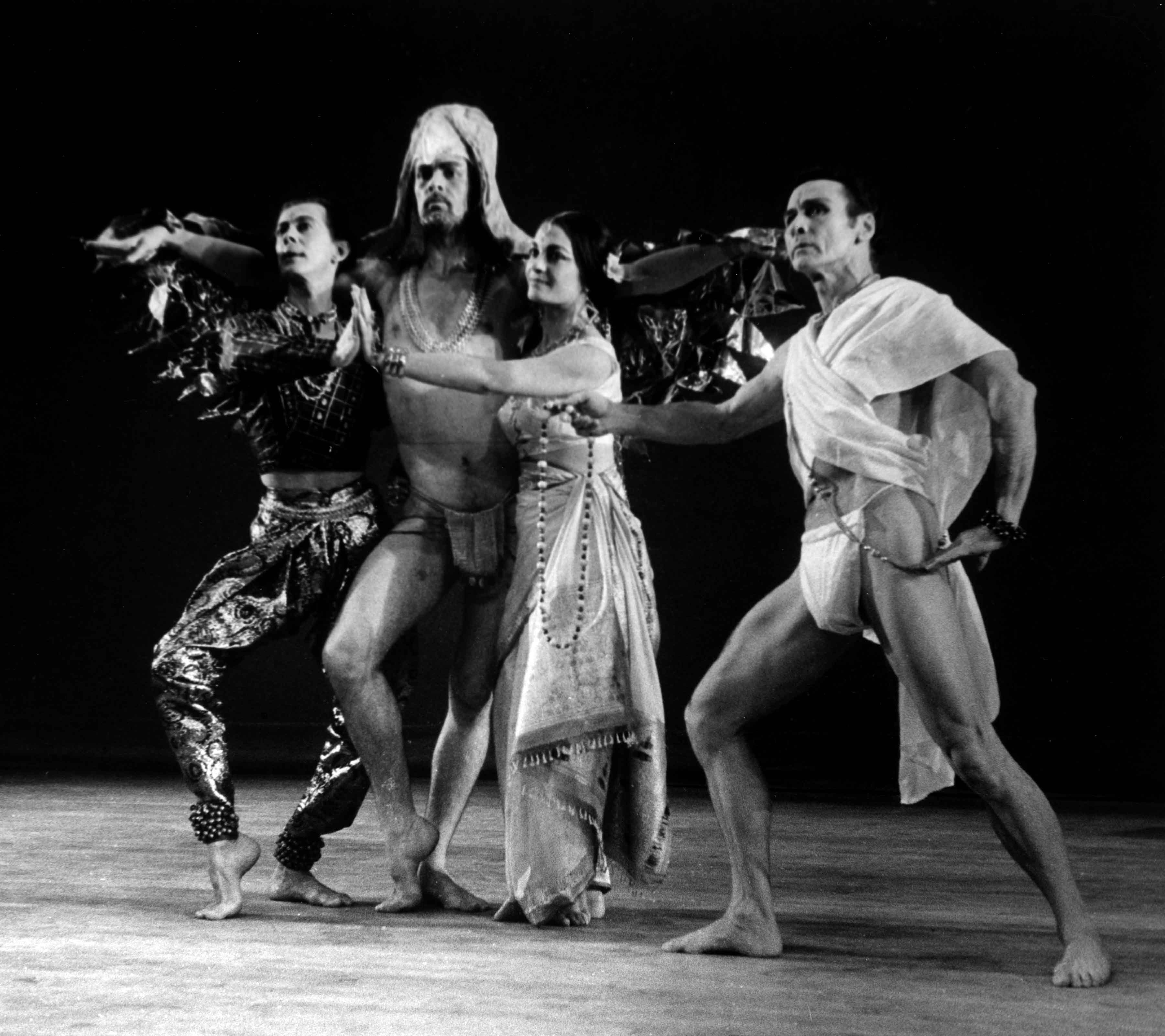

Nala Najan

Nala Najan (1932-2002), whose birth name was Roberto Rivera, was one of the prime disciples of the hereditary nattuvanar Muthukumara Pillai. Nala, like Indrani, also popularized Indian dance in the USA. He had performed at the Pillow in the late 60s and mid 70s. He was hailed “as the greatest Indian male dancer of this generation” by La Meri.

He also trained in other Indian classical dance forms such as Manipuri and Kathak.

Nala Najan performed neo-classical Bharatanatyam pieces such as Pushpanjali and Devarnama (Krishna Ni Begane Baro, “Krishna, come quickly”) and frequently acknowledges the choreography of the mimetic pieces as “Improvised” in program notes. This was probably influenced by his training under hereditary dance teachers in South India; for these teachers, improvisation was an important aspect of their dance pedagogy. Traces of this kind of improvisation can be seen later in 1997 when Lakshmi Knight, daughter of T. Balasaraswati, performed at the Pillow.

In a mode similar to the “hybrid” or “thematic” Indian-inspired dances of Ram Gopal, Nala Najan also choreographed new pieces that incorporated his Western aesthetic sensibilities into his Indian dance training. These included pieces like Homage to Vivaldi (1975), which he performed as a solo incorporating Bharatanatyam technique. According to the program description, the work was “A contemporary creation utilizing the ancient Bharata Natyam dance set within the framework of an 18th century musical form. This dance is a study in the pure abstraction of movement as defined by a traditional technique.”

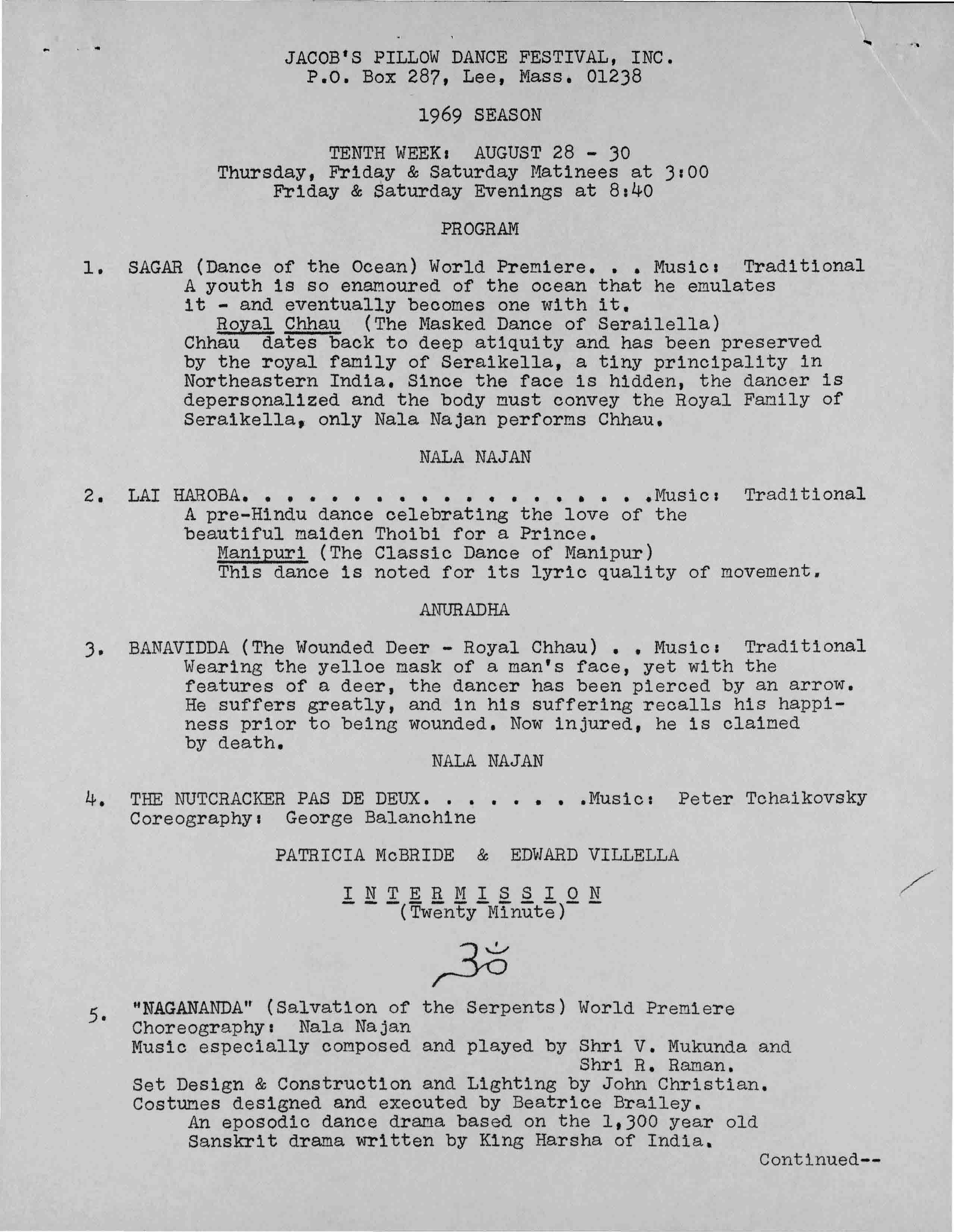

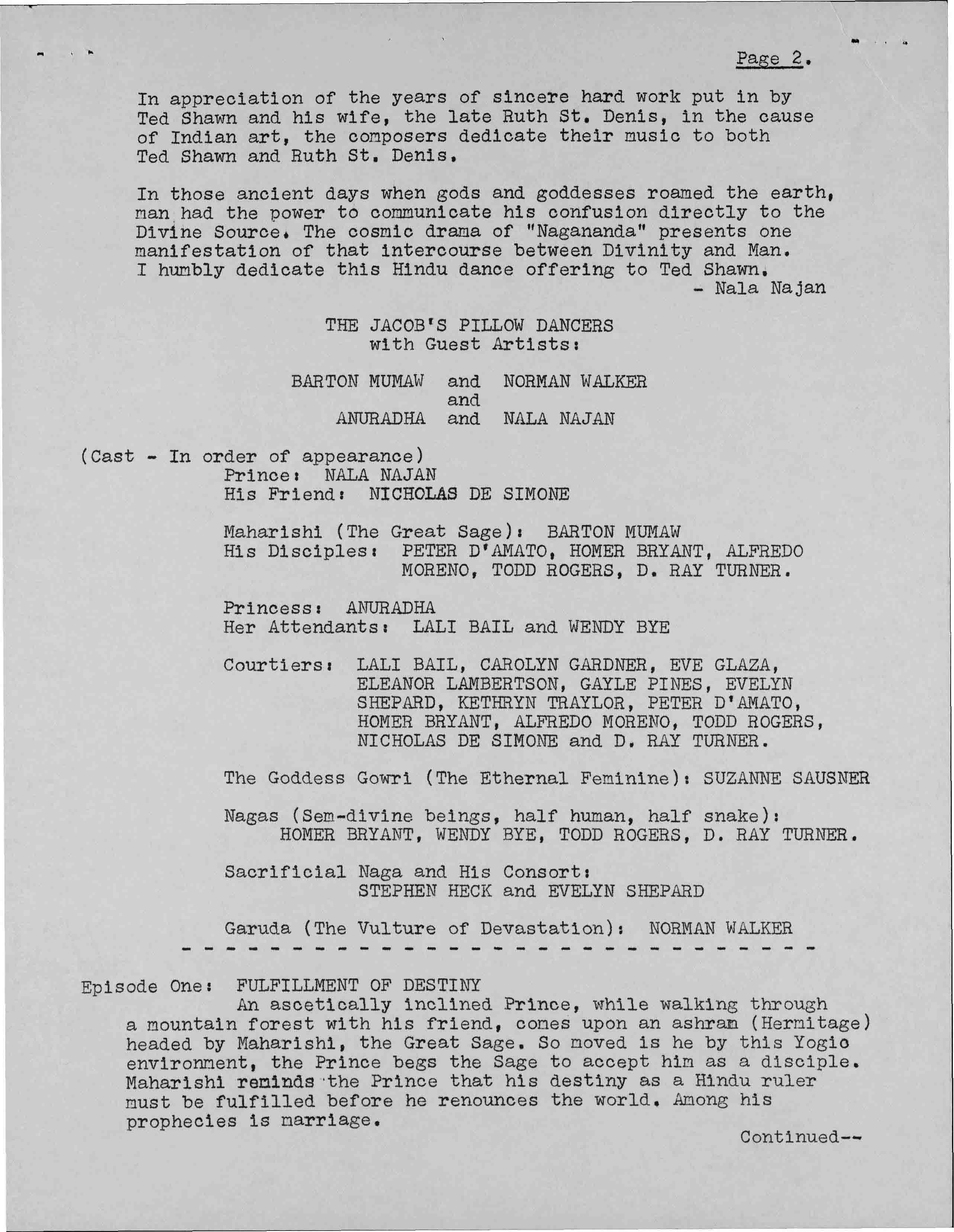

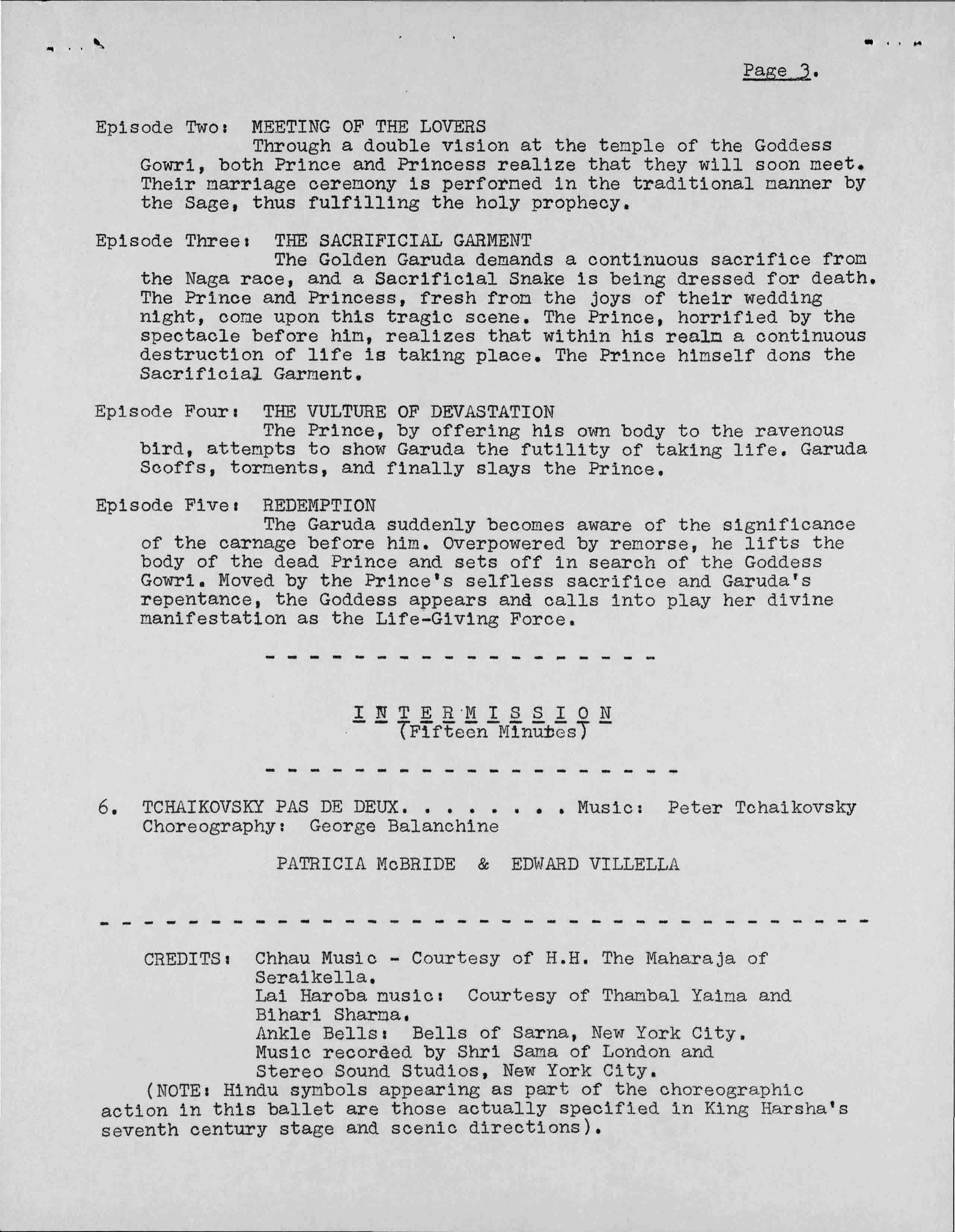

Nala Najan also choreographed what he termed “dance dramas” for the Pillow. One such piece was in Sanskrit, entitled Nagananda (Salvation of the Serpents) in which he used a cohort of both Indian and non-Indian dancers. In the dedication in the program notes Nala Najan writes, “In appreciation of the years of sincere hard work put in by Ted Shawn and his wife, the late Ruth St. Denis, in the cause of Indian art, the composers dedicate their music to both Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis. In those ancient days, when gods and goddesses roamed the earth, Man had the power to communicate his confusion directly to the Divine Source. The cosmic drama of ‘Nagananda’ presents one manifestation of that intercourse between Divinity and Man. I humbly dedicate this Hindu dance offering to Ted Shawn.”

Such statements reified the idea of Indian dance as “essentially religious” or “spiritual” among American audiences. It was only years later that these old paradigms were critically interrogated and critiqued at the Pillow through both discourse and performance by choreographers such as Hari Krishnan.

Chandralekha

From the 1990s, Indian dance performances at the Pillow were recorded on video and audiences were treated to an array of leading artists from India and the diaspora. Several “neo-classical” Indian dance styles such as Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Odissi, and Kuchipudi in addition to contemporary dance inspired by these forms were featured regularly at the Pillow. The rest of this essay will highlight the Bharatanatyam dancers and choreographers who performed both on the Pillow’s mainstage season as well as the Inside/Out series.

In 1994, Indian contemporary choreographer Chandralekha (1928-2006) and her company Chandralekkha Group presented a piece entitled Yantra. Chandralekha had initially trained in Bharatanatyam under the hereditary nattuvanar Kanchipuram Ellappa Pillai. But she was dissatisfied with the cosmetic quality of Indian classical dance in modern India and desired to make work that interrogated the dancing body as contemporary aesthetic and political resource. Thus began her prolific career as India’s most radical choreographer in the 1970s until her death in the mid-2000s. She created iconic and completely abstract contemporary Indian works exploring themes such as her visions of Indian feminism, sexuality and eroticism, and somatic resistance.

Not since Nala Najan’s Homage to Vivaldi in 1975 had Pillow audiences been exposed to a new, refreshing aesthetic of contemporary Indian dance; and Chandralekha’s work brought Bharatanatyam technique into dialogue with yoga and Indian martial arts. Her contemporary expression was heavily rooted in an Indian sensibility. The starkness of her choreography, bereft of the usual expectations of heavily ornamented Indian dance was provocative. In Yantra, she explored ancient Indian shapes and diagrams to unearth “the inner energy of the body, its vital energy zones, its sexual and spiritual potentialities.”

Yantra featured seven dancers and three musicians, including one of today’s most famous South Indian vocalists, Aruna Sairam.

Chandralekha discusses the work as a spoken text performative prologue.

Chandralekha’s austere movement vocabulary is seen clearly in this clip. Her aesthetic continues to resonate with many contemporary Indian choreographers today.

Shobana Jeyasingh

The presentation of Chandralekha’s work in 1994 was followed in 1995 by the work of visionary choreographer Shobana Jeyasingh (b. 1957) from the UK. Shobana forged another kind of new path in contemporary Indian dance with her deconstruction of Bharatanatyam based on her lived experience as an artist working in London. Shobana was initially trained in Bharatanatyam by the hereditary nattuvanar R. Samaraj. Having lived in London for several years, Shobana reimagined the classical Bharatanatyam body as an urban body, fusing it with distinctly new stylistic influences drawn from Western contemporary dance. Her company, the Shobana Jeyasingh Dance Company, made its debut at the Pillow with a double bill of two pieces: Making of Maps and Raid. Both works were performed by a cohort of six female Bharatanatyam dancers. The first piece, Making of Maps, inverted the expectation of Indian dance choreography mirroring its accompanying music. In this work, the music and the dance had distinctly independent relationships, much like in American post-modern dance of the time. The theme of Making of Maps injects neo-classical Bharatanatyam technique into an urban British world, where the dancers engage in process of self-discovery and renewal.

In the second piece, Raid, Shobana explores the technique and rules of the popular Indian street sport kabaddi from the conceptual perspective of ideas around speed, antagonism, and escape. The percussive soundscape co-composed by legendry Indian film composer Ilaiyaraaja is intentionally disrupted by the contemporary sonic composition of Glynn Perrin, forcing two different aesthetics to rub against each other, unveiling “dangerous” repercussions in the contemporary choreography.

During the post-performance discussion, Shobana discusses her unique choreographic process and discusses her dance trajectory.

The juxtaposition of the choreography of Chandralekha and Shobana Jeyasingh within the span of a year at the Pillow showcases two very different approaches to contemporary abstractions of neo-classical Bharatanatyam. After this short-lived and somewhat anomalous presentation of “innovative” Indian dance in 1994-95, for the next 15 years, the Pillow exclusively featured conventional neo-classical Indian dance.

Malavika Sarukkai

In 1996 and 1998, Malavika Sarukkai (b. 1959), the popular Bharatanatyam dancer from Chennai, India, performed two full-length solo concerts at the Pillow with her musicians. Trained by hereditary nattuvanars Kalayanasundaram Pillai and Swamimalai Rajarathnam Pillai, Malavika is known for her razor sharp technique and her own innovative choreographic solo works, exploring her own conceptualizations of time, space, and energy within the neo-classical Bharatanatyam framework.

As an independent female chorographer, Malavika discusses her own politics and how they affect her portrayal of women in Indian dance.

Lakshmi Vishwanathan

In 2002 and 2004, the Bharatanatyam dancer Lakshmi Vishwanathan from Chennai, India, performed at the Pillow. She was trained by hereditary nattuvanar Kanchipuram Ellappa Pillai. In 2004, Lakshmi brought a mixed bill of her own choreography featuring three dancers, three musicians and herself as the principal soloist. All the pieces reflected Lakshmi’s penchant towards a more populist aesthetic that was representative of Bharatanatyam as a neo-classical art in the city of Chennai (formerly Madras). The repertoire also included some of Lakshmi’s signature pieces such as the Javali (“Ni Matale”).

During a post-performance discussion, she spoke about her belief in the importance of musical training for a Bharatanatyam dancer.

Artists on Inside/Out

From 2009 onwards, the Pillow has seen several Bharatanatyam artists perform on the Inside/Out stage, including those featured here.

1. Janaki Rangarajan (2009) is a student of Padma Subrahmanyam who incorporates a hybrid technique that blends neo-classical Bharatanatyam technique with directives drawn from texts on Sanskrit aesthetics and the iconographic program of medieval Hindu temple sculpture.

2. Rukmini Vijayakumar (2012 and 2014) is a Bengaluru-based Bharatanatyam dancer and actress who dances a popular style of Bharatanatyam that is packaged for mass appeal. Trained by various teachers including Padmini Rao, Narmada, and Sundari Santhanam, Rukmini’s aesthetic draws from a variety of populist influences and sensibilities.

3. Ramya Ramnarayan (2013) is a New Jersey-based Bharatanatyam dancer trained by hereditary nattuvanar, Swamimalai Rajarathnam Pillai, who performs the signature style of her teacher in both the USA and India. She performed at the Pillow with her son Rangaraj Ramnarayan in a series of solos and duets.

4. In 2016, New York City-based artists Preeti Vasudevan (artistic director of Thresh) and Amar Ramasar (of New York City Ballet) created Études, a duet exploring hybrid expressions of Bharatanatyam and ballet with four musicians. Created as a dance dialogue between two dancers, the work deconstructs their classical dance training and reimagines a new corporeal world for their dance techniques to fuse and transform. The version performed at the Pillow in 2017 was danced by Vasudevan and Craig Hall.

Ragamala Dance Company

In 2018, Minneapolis-based Ragamala Dance Company made their debut at the Pillow with their full length work, Written in Water, represented through two religious cultures, Hinduism and Islamic Sufi traditions. Musically, Ragamala had conceived this merger by using Bharatanatyam dance and a combination of South Indian classical, jazz, and Sufi-inspired music provided by Amir ElSaffar. The production featured ten performers: five dancers and five musicians. Choreographed by Ragamala’s co-artistic directors, the mother/daughter duo Ranee Ramaswamy and Aparna Ramaswamy, this interdisciplinary production integrated live dance and music with multi-media projections and lighting design. The over-arching themes in the production included those of longing, searching, ecstasy, and spiritual transformation.

Hari Krishnan

Before I conclude, I would like to express my immense gratitude to Jacob’s Pillow for according me the honor and privilege of contributing and presenting my own work at the festival. Having trained under hereditary nattuvanar K.P.Kittappa Pillai and several female master-artists from the hereditary dance community, including R. Muthukannammal, I am a Bharatanatyam and contemporary dance artist. My work is an intrinsically personal vision of Indian dance that integrates critical dance histories, feminist politics, queer identities, and contemporary dance from global perspectives.

In 2012 as part of the 80th anniversary of the Pillow in a unique program, The Men Dancers: From the Horse’s Mouth, I joined an international cohort of male dancers as the only Indian dancer, performing a tribute to Ted Shawn and his all-male dance company.

In 2013, I presented two choreographies with my company dancers: Paul Charbonneau, Benjamin Landsberg, and Hiroshi Miyamoto. These included my solo Bharatanatyam work, The Frog Princess, and my contemporary work, I, Cyclops, an ‘east-west’ mash-up of a slash art fantasy. This was perhaps the first time Pillow audiences saw Indian dance-inspired works integrating themes of overt queer sexuality, pop-culture, and identity politics.

In 2016, as part of a double bill entitled Dances for One, I shared the evening with Flamenco dancer Marina Scannell. In a duet with percussionist Kajan Pararasasegaram, called Tiger by the Tail, we ‘stalked’ South Indian rhythmic syllables to capture a perilous urban hunt, exploiting ‘weaponized’ hands, feet and voice.

In 2018, I premiered my new work, Black Box 3 performed by my company dancer, Vinod Para, and as a Pillow Scholar-in-Residence, I facilitated a post-performance discussion for Dance and Dialogues: Classical Indian Solos with Para and a fellow artist sharing the evening, Kathak dancer Barkha Patel. I also led post-performance talks for Ragamala’s 2018 engagement.

Conclusion

Taken together, all the artists discussed in this article have created an important legacy for contemporary Bharatanatyam at the Pillow, and this essay has chronicled some of these contributions. The Bharatanatyam we see today moves in ever-shifting global directions and has grown well beyond the historical debates surrounding its reinvention in the early twentieth century, although critical discourses over nation, body, caste, religion, sexuality, and technique that were at the heart of its reinvention still circulate in the practice, pedagogy, and articulation of the form, globally. The reinvented form has also expanded beyond its twentieth-century epicenter, the city of Chennai (formerly Madras), and its pulse can now be felt in every major urban center around the world. Post-colonial and hybrid diasporic identities have given new impetus to the form. In North America, elements of Bharatanatyam dance have interfaced with contemporary dance and new kinetic vocabularies have been created by prominent second- and third-generation artists of South-Asian origin. Professional Bharatanatyam training and performance has also extended to include professional or semi-professional practitioners of non-South Asian origin, and this too has moved the dance in highly innovative directions.

Further Readings

Allen, Matthew Harp. 1997. “Rewriting the Script for South Indian Dance.” The Drama Review, 41 (3), 63-100.

Gaston, Anne-Marie. 1996. Bharata Natyam: From Temple to Theatre. Delhi: Manohar.

Gaston, Anne-Marie. 2018. Bharata Natyam Evolves: From Temple to Theatre and Back Again. Delhi: Manohar.

Khokar, Mohan. 1964. Bharata Natyam Vidwan Muthukumara Pillai. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Knight, M. Douglas Jr. 2010. Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Kothari, Sunil (ed.) 1997. Bharata Natyam. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Krishnan, Hari. 2008. “Inscribing Practice: Reconfigurations and Textualizations of Devadasi Repertoire in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century South India.” In Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India, ed. Indira Viswanathan Peterson and Davesh Soneji. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Krishnan, Hari. 2009. “From Gynemimesis to Hyper-Masculinity: The Shifting Orientations of Male Performers of South Indian Court Dance.” In When Men Dance: Choreographing Masculinities Across Borders, ed. Jennifer Fisher and Anthony Shay. New York: Oxford University Press.

Krishnan, Hari. 2019. Celluloid Classicism: Early Tamil Cinema and the Making of Modern Bharatanatyam. Wesleyan University Press.

O’Shea, Janet. 2007. At Home in the World: Bharata Natyam on the Global Stage. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Peterson, Indira Viswanathan and Davesh Soneji (eds.). 2008a. Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Pillai, Nrithya. “Breaking Bharatanatyam’s many shackles.” Indian Cultural Forum, June 9, 2020. https://indianculturalforum.in/2020/06/09/nrithya-pillai-interview-mukulika/

Popkin, Lionel. “The Complexities of Indian Dance at the Pillow.” pillowvoices.org, May 22, 2021. https://pillowvoices.org/episodes/the-complexities-of-indian-dance-at-the-pillow

Soneji, Davesh (ed.). 2010. Bharatanatyam: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Soneji, Davesh. 2012. Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Srinivasan, Amrit. 1985. “Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance.” Economic and Political Weekly 20 (44): 1869-76.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. Indian Classical Dance. New Delhi: Publications Division, Government of India, 1992.