Introduction

It’s 2001, and I have been invited to teach Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement lessons at a World Dance Conference in Houston. The organizers considered Feldenkrais to be the Switzerland of movement practices, thinking it would prepare participants for movements they had never done before. The conference allowed teachers to become participants when they finished presenting, a feast for my somatic eyes as I watched experts of one form look like novices in another.

I cherished the quality of novelty of all these new forms and recognized how nourished I felt from this new information. I couldn’t help but notice three young women who looked as comfortable in the West African dances as they did in Bharatanatyam. They seemed to easily flow from one form to another with an uncanny finesse.

Who were these women and how did they learn to do that?

It turns out they were all students at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, where studying world dance was a requirement. As recent graduates, they were carrying Dance DNA from several continents. In addition, I could see that their fluency in one form most probably contributed to their abilities in the next one. I wondered what this incredible neuro-diversity added contributed to their artistry as contemporary dancers. With their worldly bodies, these dancers had an enormous advantage as they entered into the field.

It finally dawned on me that they were evoking La Meri, the first American woman to intensely study dances from all over the world and then also perform them all over the world. La Meri was always an unsung hero of mine, even then, when I didn’t know much about her aside from her steady presence at Jacob’s Pillow during the formative years of Ted Shawn’s festivals.

Before she was La Meri, she was Russell Meriwether Hughes, born in 1899 in Louisville, Kentucky, but raised mostly as a member of the upper middle class of San Antonio, Texas, where her parents exposed her to all forms of the arts and activities. She studied ballet, violin, singing, writing, horseback riding, and shooting.

Determined to live a life on the stage, her career trajectory settled on dance, first Spanish dances, then East Indian dance, eventually blossoming in an astonishing repertoire of dances from an equally astonishing array of places.

Her solo touring led her around the globe and back. She started a school (with Ruth St. Denis for a short time), and eventually moved her operation to Cape Cod, where her teaching career had another burst of activity. She also was part of the Pillow family on and off from 1940 to 1972.

So ahead of her time in valuing the movement languages of multiple cultures, La Meri was able to switch from one form to another with remarkable ease and expertise. She not only realized the humanitarian value of such an endeavor, but its contribution to the artistic and physical health of a dancer.

La Meri Lost and Found

I never saw the three young women again, but I have told the story of witnessing these ‘millennial La Meris’ many times.

Too often, the response has been, “Mary who?”

As much as she accomplished as the leading American authority of her time on Spanish and East Indian dance, she had the unfortunate timing of developing her work simultaneously with the birth of modern dance, a completely new and distinctly American movement language. There’s no doubt that her work ended up on the sidelines of early American dance history because of that.

It took a good long while for the dance field to recognize her contributions, but they finally came around, bestowing on her a Capezio Award in 1972, and an impressive 16-page spread in the August 1978 issue of Dance Magazine.

And then she was forgotten again.

Subsequent efforts to tell her story include San Antonio dance writer Josie Neal’s work on a biography. She spent countless hours interviewing La Meri during the last eight years of her life in San Antonio. Neal died in 2001 before completing her book, and her audio tapes are now located in the Jacob’s Pillow Archives thanks to Bill Adams, a longtime disciple of La Meri’s who tracked down the tapes long after Neal’s death.

La Meri was rediscovered by the Middle Eastern dance community during her last years back in San Antonio. Noted Texas photographer Jim Murray began work on a video documentary about her life in 1987. He died before finishing it, but the Pillow has a priceless recording of La Meri being interviewed by Middle Eastern dancer Pat Taylor, where we hear a very vivid and straightforward La Meri talk about her career a year before she died in 1988.

Aside from a New York Times obituary by Jennifer Dunning, there was little fanfare when she passed, so you might say that she was forgotten for a third time.

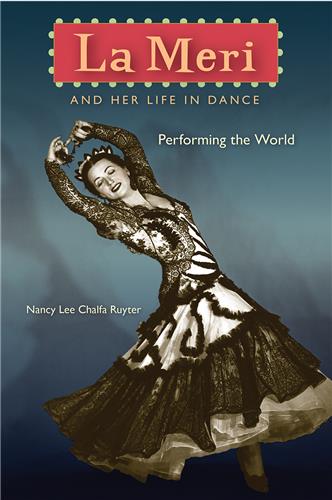

Finally in October 2019, La Meri received much deserved attention in Nancy Lee Chalfa Ruyter’s marvelously thorough book La Meri and her Life in Dance. Ruyter, a renowned dance scholar, former student and life-long friend of La Meri, brings us into the pace of her life in her exhaustive tome, uncovering the most detailed minutiae of her long, layered, and incredibly nimble career.

The subheader of Ruyter’s book, “Performing the World,” gets to the heart of La Meri’s contribution. What happens when you put the world in your body? These techniques, alone or together, can act as a fundamental dance form much in the way ballet and modern can.

Ruyter details the hectic texture of international touring during the early part of the 20th century, taking us on a whirlwind journey of the ups and downs of La Meri’s adventurous life, which for the most part was fraught with financial and artistic insecurity, and multiple attempts to establish the importance of learning and performing world dances. The multitude and the magnitude of La Meri’s accomplishments jump off the page in Ruyter’s vivid descriptions, so much so that her subject’s relative obscurity is all the more remarkable.

Beyond Ballet and Modern Dance

Her career leaves us much to admire and also question in light of today’s examination of cultural appropriation. That alone could be the subject of another essay. Yet we know that she cared deeply about learning as much as possible about what she was presenting on stage and developed her own system for vetting the accuracy of her work.

La Meri wanted us to consider dance as a vast landscape of movement possibilities. “Ballet is just another form of dance,” she remarked in the Murray video in discussing dominance of ballet, a concept that is front and center in colleges and universities as they begin the process of dismantling the ballet/modern dance hierarchy to include more non-western forms.

Just like the young dancers from Sam Houston State, her uncanny ability to learn multiple dance forms improved as she expanded her repertoire. Throughout her performing life, which was much longer than that of most dancers, she showed us the value of being a multi-form learner.

La Meri considered herself part of the larger world of dance, and she even said so in Murray’s video. She also wanted to include world dance directly in the teaching of modern dance, which we can see in the below clip. She rejected the idea that world forms belong to the category of “otherness,” and worked to bring this material into the center of contemporary dance.

La Meri at Jacob’s Pillow

As outlined in Ruyter’s book, La Meri’s career traversed various fits and starts, yet she was fast on her feet to reinvent herself. When World War II abruptly ended her international performing career, teaching became necessary for her livelihood.

One day, Ruth St. Denis showed up to one of her performances and strongly suggested that they start a school together, and that they did with New York City’s School of Natya in 1940. La Meri’s deep appreciation of St. Denis started in San Antonio when she saw Denishawn in its inaugural 1914 tour. The show made a life-changing impression on the then tween-age girl.

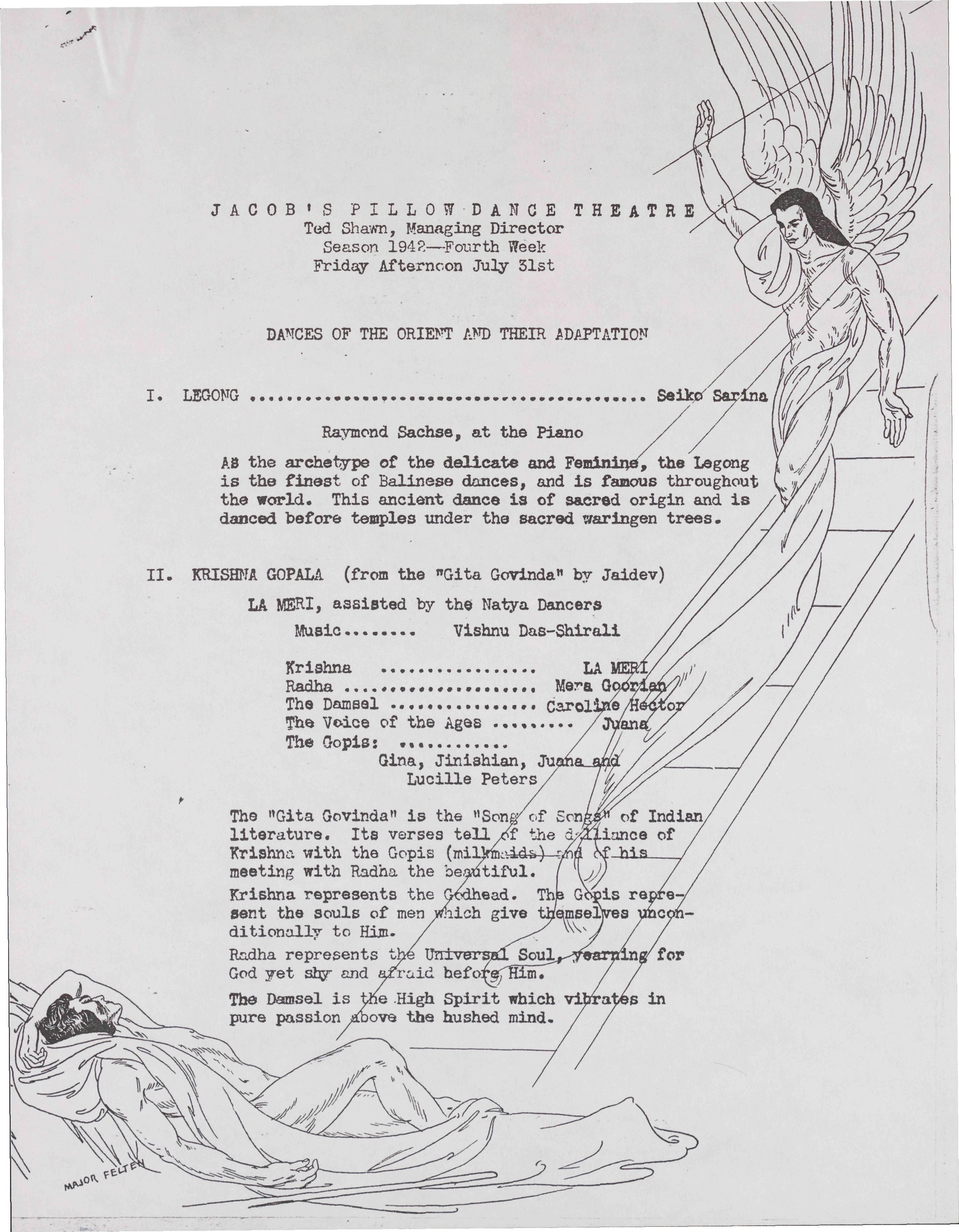

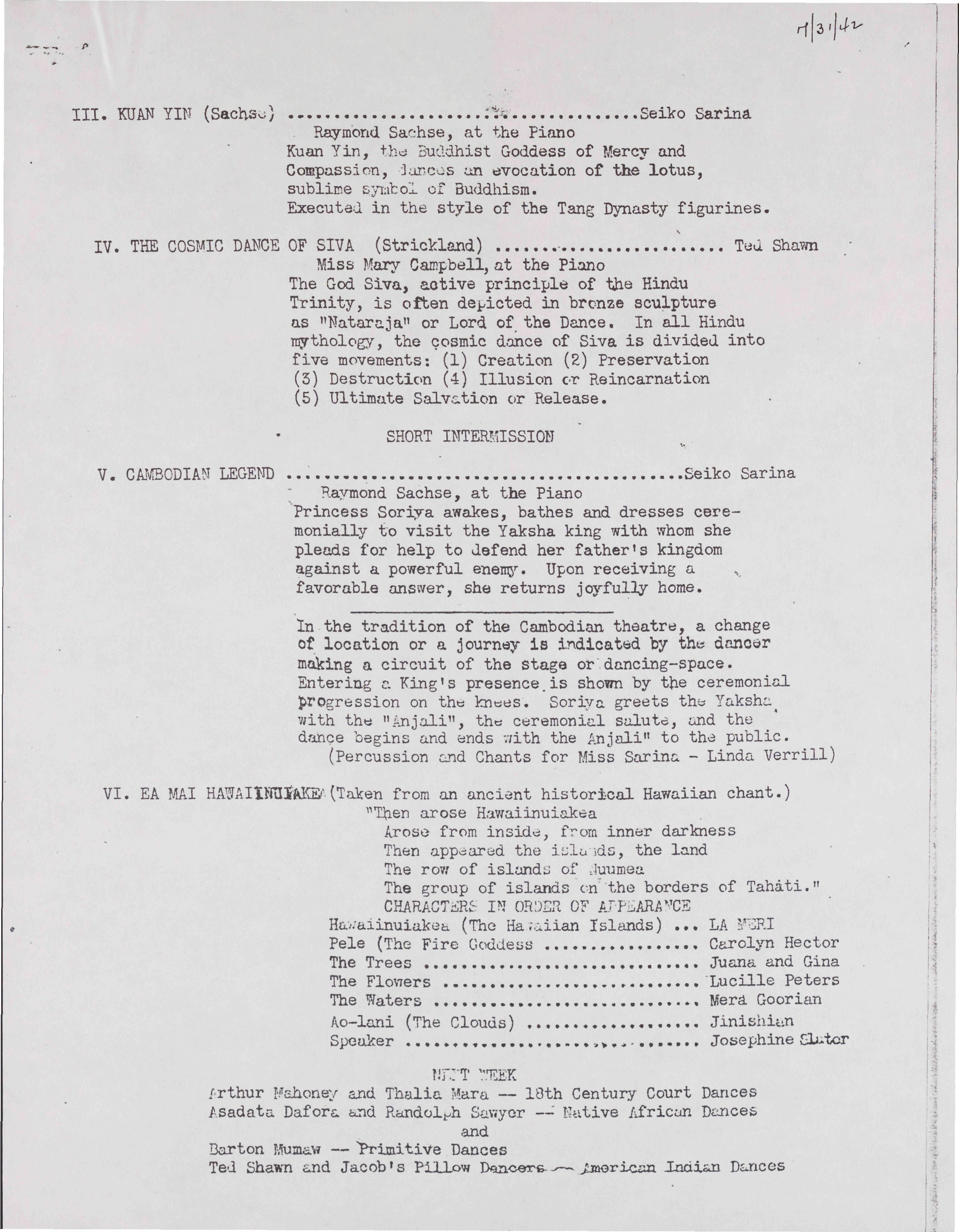

St. Denis provided La Meri’s entry into the Jacob’s Pillow fold, when Ted Shawn invited the Natya Dancers up for a “Hindu Week” in 1940. Shawn had originally asked Argentinita to teach, but St. Denis suggested that La Meri teach in her place, and La Meri also performed a program of Oriental and Spanish in addition to presenting three lectures.

On a Thursday afternoon, July 30, 1942 with “Dances of the Orient and Their Adaptation” we find one of La Meri’s first program listings in Deva Murti (Five Aspects of the Supreme Goddess), which solidified her presence at the Pillow, and underlined her further development as a teacher.

Like much of everything in her life, skills came by way of necessity. We learn from her letters and her book Dance Out the Answer that she wasn’t often taking dance classes during her travels as the practitioners were dancers and not necessarily teachers. So the act of learning a dance often meant standing behind a dancer and picking up the material on her own. Her life as a student must have influenced her life as a teacher. She learned to quickly grasp the central architecture of a form, honing in on central values easily. She had to learn quickly, as the next day she might be in a different town, standing behind a different performer.

Mary Martha Lappe, considered one of the mothers of dance in Texas, studied East Indian and Spanish dance with La Meri during the 1950s at the Pillow while she was still a student at Texas Woman’s University. Lappe does a quick run-through of the hand mudras before telling me about her experience. “When La Meri taught Flamenco, she was fiery, passionate, and very dramatic. I recall her watching our class reproducing a flamenco combination for her as she sat in a very sensual, superior pose with an arched back, both hands on her hips and a cigarette dangling from her lips. When she taught us East Indian dances, she became very calm and contained, almost ethereal. Even so, she could accentuate the smallest details of using her hands and facial muscles with great control and remarkable precision. She was able to convey the character of each form so well, and express such a range of emotion.”

Ann Hutchinson Guest, one of the founders of the Dance Notation Bureau, and a dance legend in her own right, also studied Spanish and East Indian Dance forms with La Meri in 1942. Guest’s face lit up at the mere mention of La Meri.

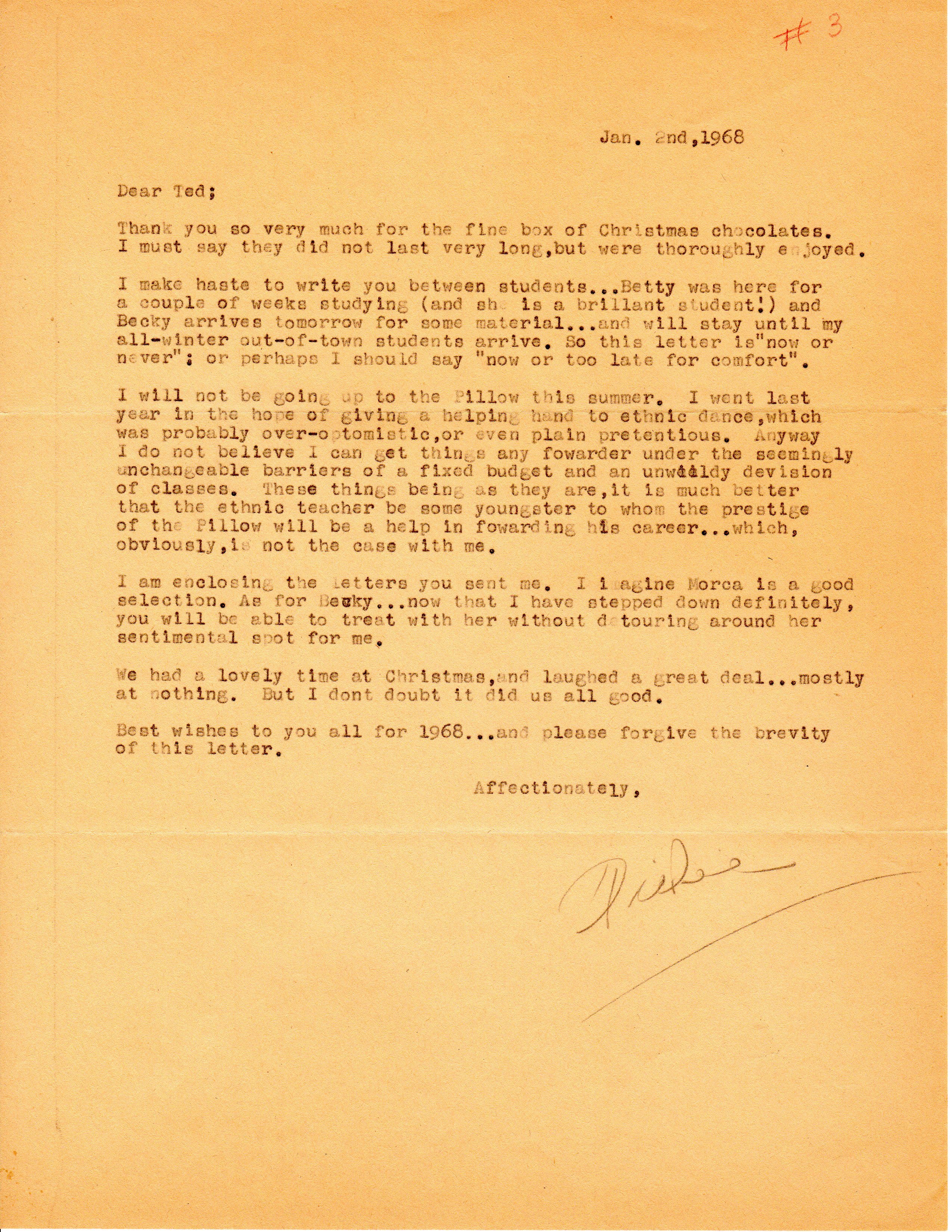

“She was a marvelous teacher,” she said, acknowledging not only her level of expertise but her deep enthusiasm for sharing her knowledge. Guest also acknowledged that La Meri was sometimes overlooked during the surging development of American modern dance. And that situation led to some disappointments at the Pillow in the effort to accentuate the significance of world dance.

Although Shawn and La Meri had a complicated relationship that had its own highs and lows, her Pillow experiences continued to build her reputation as a performer and teacher, along with bolstering the importance of world dance on the American concert stage.

Yet, looking back at her life, La Meri describes her tenure at the Pillow as mostly “marvelous” in that she was in a community of dance leaders. It was at the Pillow where she crossed paths with Antony Tudor, who then invited her to set her Four Seasons on Juilliard students. We not only see her fluency as a fusion choreographer, but we can also witness a very young Philippine “Pina” Bausch performing the lead.

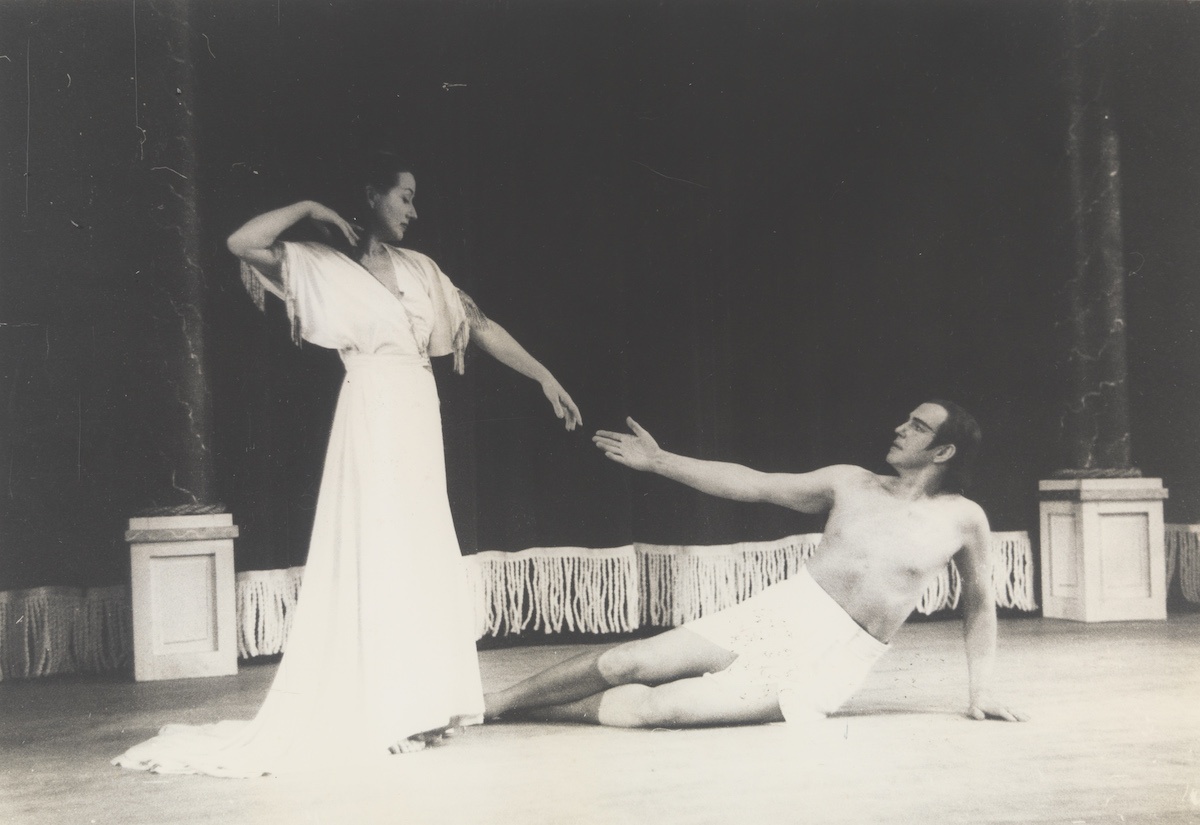

La Meri was at her most creative when she gave her own body open borders letting the world inside her own skin, We see a perfect example of this in one of her most popular works from 1944, Swan Lake.

We have seen examples of disciplines other than ballet or contemporary proving their flexibility as dance forms right here at the Pillow. Consider how Aakash Odedra, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Ephrat Asherie carry La Meri’s global vocabulary into this generation. They embody a later chapter in La Meri’s legacy as they push the boundaries of their training.

We only need to glance at the wealth of international voices represented on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive to see that the expansive thinking that La Meri brought to the Pillow continues, not only by presenting companies from all over the world, but acknowledging that every form of dance has meaning and value, and can provide a base for exploration, creativity, and cross cultural expression.