Introduction

Thud. Crash. Wham. Punch. Bam. Smash. Grunt. Gasp. Reading that list, seeing those words, one might assume that they come from the panels of a comic strip fight scene in a Batman comic strip. Thick black letters, accented by exclamation points and asterisks, making meaning in both their form and content. However, there’s no comic book quoting here. Instead, this is a list of words used by dance critics to give emphasis to their movement descriptions of the work of Elizabeth Streb.

I first came to know about the work of Elizabeth Streb in 1994. I was living then in California seeing a lot of Los Angeles-based choreographers’ work that was loosely being categorized as “hyper-dance.” A cover story by Los Angeles Times dance critic Lewis Segal was titled “Dance to the Edge: A controversial L.A. modern dance trend that some are calling Hyperdance emphasizes athleticism, endurance and risk, serving as a timely metaphor for survival in an age of disaster”; in it, Segal interviewed six choreographers. (Lewis Segal, “Cover Story: Dance to the Edge.” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1994) While no one other than Segal mentioned Streb in the article, her name was always in the air in the lobbies before and after the so-called “hyper-dance” shows. These “hyper-dances” shared a sense of attack, abandon, and physicality that was definitely exciting. I wondered at the time whether that was enough to make the high impact, potentially dangerous physicality worth it.

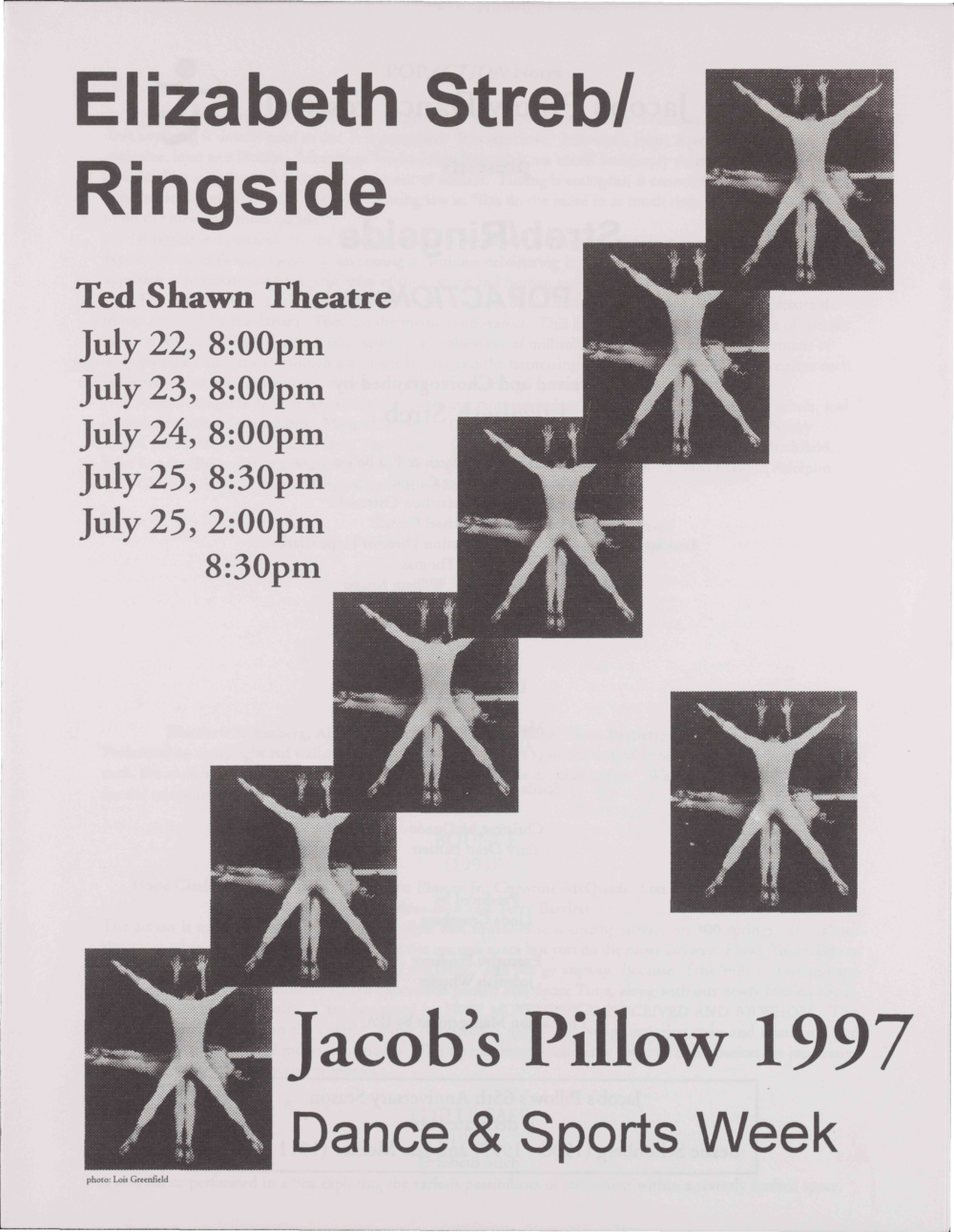

As I anticipated my first direct encounter with Streb’s work not long after in 1997 at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, I was already slightly prejudiced against it. Thinking back, perhaps I was in line with dance writer Jack Anderson who wrote at the time, “Ms. Streb merely emphasizes action for the sake of action, strain for the sake of strain and force for the sake of force. And so she makes her dancers huff and puff and throw themselves against walls.” Jack Anderson, “ DANCE REVIEW; Bouncing, Dangling And Diving.” New York Times, December 16, 1995

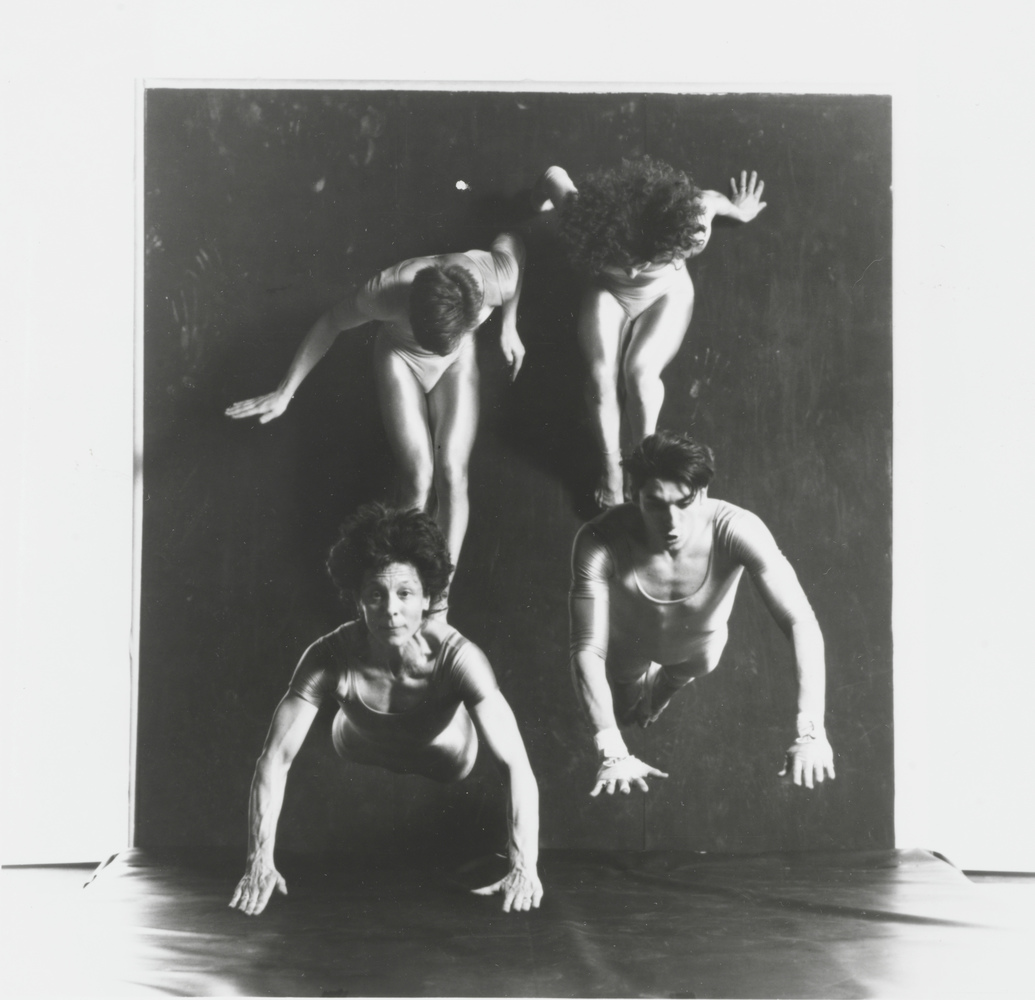

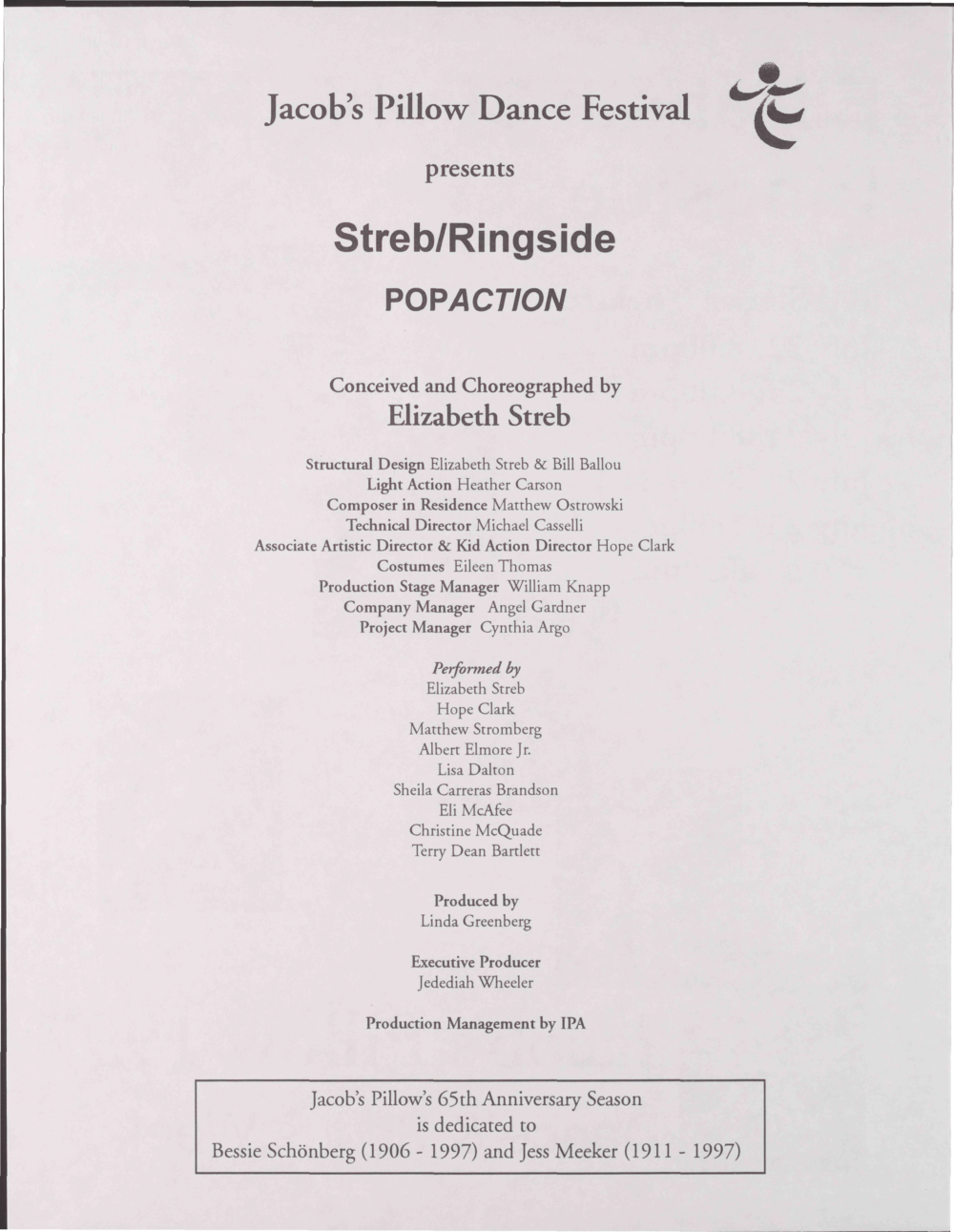

But then I saw the work and Elizabeth Streb blew my mind. As Pillow scholar David Gere wrote in his PillowNote, “We see…action. We see what the body is capable of. We see how gravity works on the body. And how the body can work with and against gravity.” At that time, Streb referred to her work as “POP-ACTION.”

Early Years

All of the things that we take as fundamental in choreography—understandings of space, time, and energy are exuberantly and vitally present in Streb’s work. Dancers fly through the air, slam into walls and into each other, drop from great heights, catch each other, support each other, contend with large pieces of equipment—some familiar and some unfamiliar called action machines. All of it with great risk, seeming fearlessness and with a sense of fun. The performers heightened readiness and physical aptitude combine with precise timing. Without that split second timing, things would get dangerous. Works often take their titles from the actions in the dances—such as Bounce, Drop, Human Fountain, Breakthru.

After graduating as a dance major from SUNY Brockport, Streb donned a leather jacket and rode a motorcycle from New York to California to participate in a dance workshop taught by Merce Cunningham in 1972. She wrote about her experience in her wonderful 2010 memoir Streb: How to Become an Extreme Action Hero: “I wanted to take that workshop because of the specificity of the training—it was all about excavating body parts, not unlike ballet. We worked on the initiation of motion, and how that initiation is peculiar to distinct parts of the body.”

She went on to say that Cunningham was able to: “mechanize the functions of the body in ways that I thought were acutely compelling, merely by using the body against itself. The struggle, the intensity of this “againstness,” made the drama and depth…He showed us that perhaps there is nothing gentle or even necessarily beautiful about the profound, true, physical, human moment of the body.”

Streb took her understanding of what she learned from Cunningham and others and exploded it. The mechanics of the Cunningham body became the mechanics of multiple bodies working with and against each other. She magnified the struggle and intensity of the singular body by exploring possibilities suggested not by dance technique per se but by physics. And answered those questions by training her body and others to achieve remarkable displays of power, strength, action, and courage.

Career

In a Dance Magazine essay titled “Why I Choreograph,” Streb wrote: “The method I employ to choreograph is to construct and answer necessary and sufficient questions about motion that have an immediate visceral and kinesthetic effect on spectators. I attempt to recalibrate the syntax, morphology, and grammar of the fundamental, indivisible aspects of motion on earth.” “Why I Choreograph: Elizabeth Streb.” Dance Magazine March 28, 2012

Part of the acceptance has comes from Streb’s persistence. She has not backed down from her own vision of the world. New York Times dance writer Siobhan Burke reflected on Streb’s career, saying,

In her loud, unflinching explorations of physics, she has, over decades, devised what looks like her own Olympic sport.”

That kind of aesthetic and kinesthetic bravery is what puts the best choreographers at the vanguard of the arts.

Streb has led audiences to consider the people who do the work, with shared respect for men and women. There are no differences based on gender in Streb’s work; there are only differences in bodies. She recounts her philosophy as:

“’You do the move in as pure and complete a manner as is possible to do that particular move, in that space, with that body, at this time, on earth.’ You ARE a move. You become the ACTION. Therefore, if successful, what is noticed is the ACTION, not the body.” Elizabeth Streb, “POP-ACTION” Performing Arts Journal, The Johns Hopkins University Press NO. 53 (1996), 72-76.

The 1997 season was the sole residency of the company thus far at Jacob’s Pillow. In addition to the performances in the Ted Shawn Theatre, Streb company members led a community program that resulted in Kid Action. Streb participated in a PillowTalk called “Dance and Sports” alongside choreographers Susan Marshall and David Dorfman, and former New York Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton.

Streb’s commitment to science recognizes that each body does each action in its own time and space. However, no matter what proper physics terms define the action or the move, the philosophical nomenclature is anything but neutral. Streb acknowledged that in an interview with the New York Times. “This metaphor has political implications for women…Impact for women has a whole different portent than it does for men. The experience is not neutral, because the female of the species is usually smaller, more vulnerable. This work empowers females. It changes the way you see the world.” Robert Johnson, “Tethering Newton’s Apple to a Bungee Cord.” New York Times December 14, 1997

Streb’s work has been recognized through numerous awards and grants, including a MacArthur and two “Bessies,” the New York Dance and Performance Award. She returned the Pillow in 2015 during Weekend Out, to screen the award-winning documentary film about her life and work titled Born to Fly and participate in a post-screening discussion following the film.

PUBLISHED March 2017