Introduction

It may look as if the artist is behaving like an activist, when actually all she is doing is building a world in which she can live and work."

While groundbreaking female and femme (all who operate in the world with an embodiment of femininity) choreographers and performers have been pushing the feminist lens forward in a diverse array of spaces and in a variety of movement practices, this essay focuses on women choreographers whose works are accessible through the Jacob’s Pillow Archives and who have found ways to hold space over decades, intentionally employing their voices to amplify the stories and experiences of women using the concert dance stage, or a performative space, as a platform. The choreographers discussed in this essay also intentionally work within the communities they reside in; embrace, cultivate, and empower the individual voices they are working with; hold a strong belief in the power of mentoring; and work within educational systems. They also seem to hold a belief in dance as a way to express our stories, make sense of the world, and as a path towards healing and/or change.

Considered here are three women-centered choreographic works of Liz Lerman, Ananya Chatterjea, and Kate Weare; all of whom in their own ways, weave their artistic vision with the aesthetic and political in powerful signification. They not only touch upon the institutionalized oppression of women and commitment to resist, but also offer hope, joy, and both collective and individual identity, while redefining notions of beauty and empowerment.Chatterjea, Ananya. Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies Through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), preface xiv, p .11-12. I believe these choreographers have found success in “disrupting conventional structures of representation without erasing the material presence of the body.”Albright, Ann Cooper, Engaging Bodies: The Politics and Poetics of Corporeality (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), p. 62.

Witch Hunt

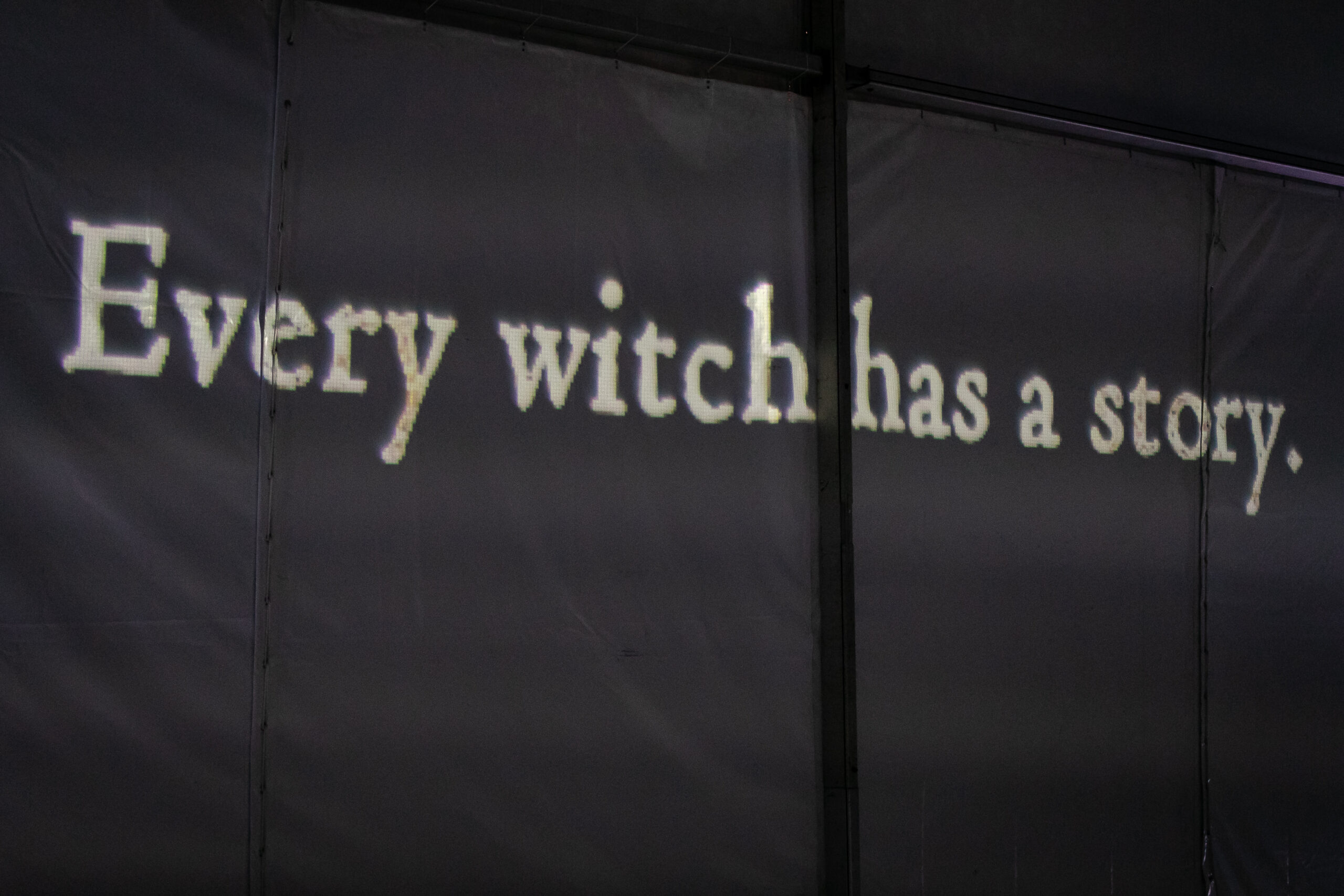

“Every witch has a story.” This statement is projected on a white backdrop behind a female-presenting soloist in white at the beginning of Liz Lerman’s Wicked Bodies, a multidisciplinary piece performed at Jacob’s Pillow in 2022 inside a large tent with sounds of nature and howling, and dancers dispersed throughout the space, as well as in the audience. The sound shifts into more intense crackling as the dancers begin to move through space varying between large, full bodied movement and gestures. The sound softens and one white male-presenting dancer begins speaking with images projected behind him and the statement “witches have a lot of jobs…” He makes statements about stereotypes associated with witches and “remembering movement of extinct creatures.” These stories amplify and disrupt the misogynistic roots, cultural impact, and modern resonance of the label “witch.” Historically, the idea of a “witch” emerged as a means of exerting societal control over independent women, particularly those practicing medicinal techniques in reproductive healthcare. Thus, images of women, or “witches,” eating babies emerged as propaganda. As we consider the idea of “extinct creatures” within the context of Lerman’s Wicked Bodies, I reflect upon events such as the Salem Witch Trials, which exemplified how fear and propaganda were used to demonize women, leading to tragic consequences. Will history continue to repeat itself?

The imagery and sound used throughout Wicked Bodies is significant, visceral, potent, and impactful. The audience becomes fully immersed in the experience, sometimes spectating, sometimes a part of it, sometimes both simultaneously. In the post performance discussion, the idea of “knowledge systems” resonates and echoes long after. What knowledge is celebrated? What knowledge is erased? What knowledge is criminalized? And what are the ways we embody those knowledge systems? Lerman describes Wicked Bodies as “a history of sly, grotesque, sensual, wildly creative women that every culture carries in clichés, stereotypes, and fictions because they are actually very real and very present.” Liz Lerman’s works are embodied, presented, and performed by intergenerational artists of varying genders, races, and identities who are an integral part of the process, and whose personal stories often become a part of the work. Lerman also brilliantly utilizes “other” spaces to share her work. This feels both intentional and significant in that she is taking control of the kinds of spaces and ways the “body is on display” and/or in relationship to the viewers, witnesses, or participants of the works. That, in itself, could be seen as a political act. Wicked Bodies, to me, shows the many ways in which outspoken, creative, and strong women have been criminalized and demeaned throughout history as a way to control and instill fear as well as justify violence against women. I also believe the work draws attention to the historical criminalization, erasure of stories, and violence against all bodies society has deemed as “other,” or existing outside of white cis-heteropatriarchy social norms. Lerman uses wildly creative ways to tell stories with various intersections of dancers’ identities that are so fully embodied, one is forced to think, connect, and question.

Dancing for Survival

We understand more than ever that the stakes in dancing for life and survival are high."

When viewing Ananya Chatterjea’s work Nün Gherāo: Surrounded by Salt (subtitled Salt Water Stories) as part of a Jacob’s Pillow Lab (2022), or work in progress showing, I was blown away by the rhythmic power in the sound of feet, the space held and shaped with these women’s bodies and voices, the physical presence and power of the salt and other objects, and the layers of storytelling through various movement mediums and sounds. Ananya Chatterjea is a professor at the University of Minnesota; a leader in transnational feminism; founder, choreographer and artistic director of Ananya Dance Theatre; and often a performer in her own work.

Ananya Dance Theatre (ADT) is “an ensemble company of BIPOC women and femme professional dance artists who create and present social justice choreography” whose work “electrifies the intersectional frontiers of artistic excellence, social justice, and community-embedded practice, inspired by the lives and dreams of BIPOC women and femmes from the global majority…to thrift the landscape of mainstream culture and empower diverse stories.”“What We Do.” Ananya Dance Theatre: About, 2004. https://www.ananyadancetheatre.org/about. Accessed December 1, 2024. During the Pillow Lab while building the work Nün Gherāo, Chatterjea spoke about the practice of social justice through dance, stating that the practice of justice requires discipline, intention, and clarity; and movement, she believes, has all of those elements. She continued by sharing the need to “communicate and bring light where light may not be always.” Inside the Pillow Lab: Ananya Dance Theatre, 2022. Jacob’s Pillow Archives MI#7225. This idea of shedding light through a social justice lens is evident in all of Chatterjea’s work, as well as the presence and powerful impact of all stories intentionally being told through the minds, spirit, bodies, and voices of BIPOC women and femmes.

Chatterjea’s work is embodied through multiple movement practices and foundations including Yorchhā™, Shawngrām™, Aanch, Daak, and social justice choreographic methodology to celebrate transnational feminist practice to articulate stories of BIPOC women from global communities of color.“Foundations of our practice.” Ananya Dance Theatre: About, 2004. https://www.ananyadancetheatre.org/foundations-of-our-practice. Accessed December 1, 2024.

Nün Gherāo: Surrounded by Salt (subtitled Salt Water Stories) uses a 1978-79 massacre on the Marichjhapi Island in West Bengal, India, (where Chatterjea is from) as the starting point to explore betrayal, dispossession, and exile, and the desperate global resistance against great odds that fuels hope and survival. The embodied work does not literally tell the story, but explores themes of displacement, tragedy, loss, heartbreak, betrayal, waiting for those we love to return, and the different memories and stories we hold onto or have to let go of. While this piece is not about women explicitly, the fact this it is being performed and embodied by women—thus as translator of the stories—shows the significance of how women’s bodies can be used to tell universal human stories, and how women with different experiences and backgrounds can relate to the themes being explored intellectually, emotionally, and physically.

For example, as Chatterjea began developing this work, she asked all the dancers what their relationship to saltwater was. Alexis Arminta Reneé, who is from Maryland and the Chesapeake area, talked about her ancestral connection to crabs and the way enslaved Black people used to use them. This conversation led to the development of a section of the work called “crab walk.” Alexis shared in a post-performance discussion that “Each person’s relationship to salt water and salt in general and ancestry and archetypes that Ananya assigned to us start to move into the space and start to develop into the world and to the movement and sound that Spirit ended up scoring.

The work in progress unfolds with multiple layers of sound, movement, and meaning with rhythm, space, objects, and relationships invoking powerful images and symbolism. We see prevalent images of fists over the mouth and the use of rope, salt, and jars. The fist over the mouth perhaps represents words unspoken, unsaid, or the act of being silenced; dancers also move with a readiness to fight or defend. Using a large circle, where dancers are swirling, meeting and parting is very representative of the cyclical nature of life, death, and societal constructs; and with one spoken phrase by the vocalist all dancers put a fist up to the sky. In my opinion, Chatterjea has mastered duration and when to shift dynamically as well as how space can be used most effectively to convey a message and/or image. Chatterjea’s work is not just seen, it is experienced; one is left with the resonance of vibrations in the body from both movement and sound, visceral and emotional connections towards these women’s experiences, stories, and concerns, lingering questions, and the cyclical arrival at both loss and hope.

Power Dynamics of Touch

In 2009, Bridge of Sighs, choreographed by Kate Weare, left a deep and lasting impact on me (then a graduate student) as to how the power of touch can be used to dismantle patriarchal systems and societal constructs of power when it’s a female voice directing it. While I already deeply identified with using touch as an integral choreographic tool in my own work—as well as considering myself a feminist who had seen numerous works by female-identifying choreographers—I had never seen touch used in such an intimate, tactile, rhythmic, and unapologetically fierce way with powerfully clear, present, visceral, and emotional implications. Power, strength, tenderness, and vulnerability are shown by all bodies onstage, varying between who is directing what to happen or who is supporting whom. When we see different genders embodying the same vocabularies in different contexts, how does this change meanings for the viewer as different bodies perform movements or affinities we might associate with particular masculine or feminine stereotypes? For instance, does the meaning change when we see two men doing a chest bump, versus a woman and man chest bumping, versus two women chest bumping?

Kate Weare Company, made up of both male and female identifying dancers, “charts a contemporary view of humanism by placing women at the center of the human story amidst the violence, sensuality, and yearning for intimacy that mark our age. Weare’s work explores the undercurrents in relationships—both tender and stark—by drawing on our most basic urges to move and decode movement.”“About Us.” Kate Weare Company : About Us, 2005. https://kateweare.com/about. Accessed December 1, 2024. In an interview at Jacob’s Pillow in 2008 when she was creating Bridge of Sighs, Weare spoke about how she has always been fascinated by relationships and “how we stand in relationship to each other in lots of fleeting moments.” She discusses how clear and vivid the body is as a communicator of information unspoken and how it guides some of her embodied research. She also mentions how power and “how we shift and trade and negotiate power outside of language” also influences relationships that develop within her work. She uses partnering and social dance as an example of how there is constant shifting and negotiating. “You are reckoning so much with sharing center; it’s a metaphor for relationships. Social dance is brilliant at that because in order to communicate you have to give up the center, give up centrality, and I think that’s an incredible ‘in’ to how relationships can flow or be blocked.”Kate Weare Showing, April 17 2008. Jacob’s Pillow Archives MI#3514.

Bridge of Sighs explores relationships and interactions, built from truths and responding to sensations in the moment, thus showing a complex layering of stories and continuously shifting power dynamics. As we see different pairings of dancers embodying material that resurfaces, we experience how societal constructs of gender and power, subconsciously placed upon these bodies, influence our perceptions of the relationships and stories being shared. The work includes a male-female duet, which later became known as the “slappy duet,” during which they slap each other’s bodies in varying ways, juxtaposed with sensual and tender moments of touch and embraces; each dancer showcasing both power and vulnerability and igniting a visceral response as well as a complex influx of emotions. How might this response have changed if this duet was between two male-presenting dancers or two female-presenting dancers? Thus the power dynamics of touch in relation to the societal and power constructs surrounding gender identities influence audience experiences and perceptions. Weare’s work, in my opinion, dismantles this system as she uses the sensuality of touch to break down and reimagine power constructs between gendered bodies that are complex, truthful, and continuously shifting and questioning.

By looking at these particular works of Liz Lerman, Ananya Chatterjea, and Kate Weare through the lens of embodied lineages and “herstories” with the woman’s body as the archive, we see beyond (but not ignore) the physical landscape or presentational body. “She is and is not her body. She cannot be reduced to her body, but she is not separate from it.”Sandler, Julie. “Standing In Awe, Sitting In Judgement,” essay, in Dancing Female: Lives and Issues of Women in Contemporary Dance (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997), 197. The body, with its social, cultural, and political representations, showcases complex shared experiences which can celebrate both individual difference and collective community.

Bibliography

“About Us.” Kate Weare Company : About Us, 2005. https://kateweare.com/about. Accessed December 1, 2024.

Albright, Ann Cooper, Engaging Bodies: The Politics and Poetics of Corporeality (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013)

Chatterjea, Ananya. Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies Through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004)

Chatterjea, Ananya, Hui Niu Wilcox, and Alessandra Lebea Williams. Dancing Transnational Feminisms: Ananya Dance Theatre and the Art of Social Justice. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2022)

“Foundations of our practice.” Ananya Dance Theatre: About, 2004. https://www.ananyadancetheatre.org/foundations-of-our-practice. Accessed December 1, 2024.

Halprin, Anna, and Rachel Kaplan. “Introduction.” Essay. In Making Dances That Matter, 3. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019)

Inside the Pillow Lab: Ananya Dance Theatre, 2022. Jacob’s Pillow Archives MI#7225.

Kate Weare Showing, April 17 2008. Jacob’s Pillow Archives MI#3514.

Sandler, Julie. “Standing In Awe, Sitting In Judgement,” essay, in Dancing Female: Lives and Issues of Women in Contemporary Dance (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997)

“What We Do.” Ananya Dance Theatre: About, 2004. https://www.ananyadancetheatre.org/about. Accessed December 1, 2024.