Dance and Architecture

There’s an old saw that gets bandied about: “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture.” It’s been variously attributed to Elvis Costello, Miles Davis, and Steve Martin. The problem with this adage is that not only do people love to talk about music, but even more importantly, dance is always a little bit about architecture. Both dance—or perhaps better said, choreography—and architecture concern themselves with space. Formal design elements such as shape, angle, perspective, and line couple with moving bodies through space in both endeavors. While choreographer Merce Cunningham borrowed from Einstein to famously state, “There are no fixed points in space,” architect Annie K. Kwon thinks that architecture and dance “steal from each other; they shift and merge and become something unexpected.” In both worlds, space gains meaning from being inhabited.

Structure and Sadness

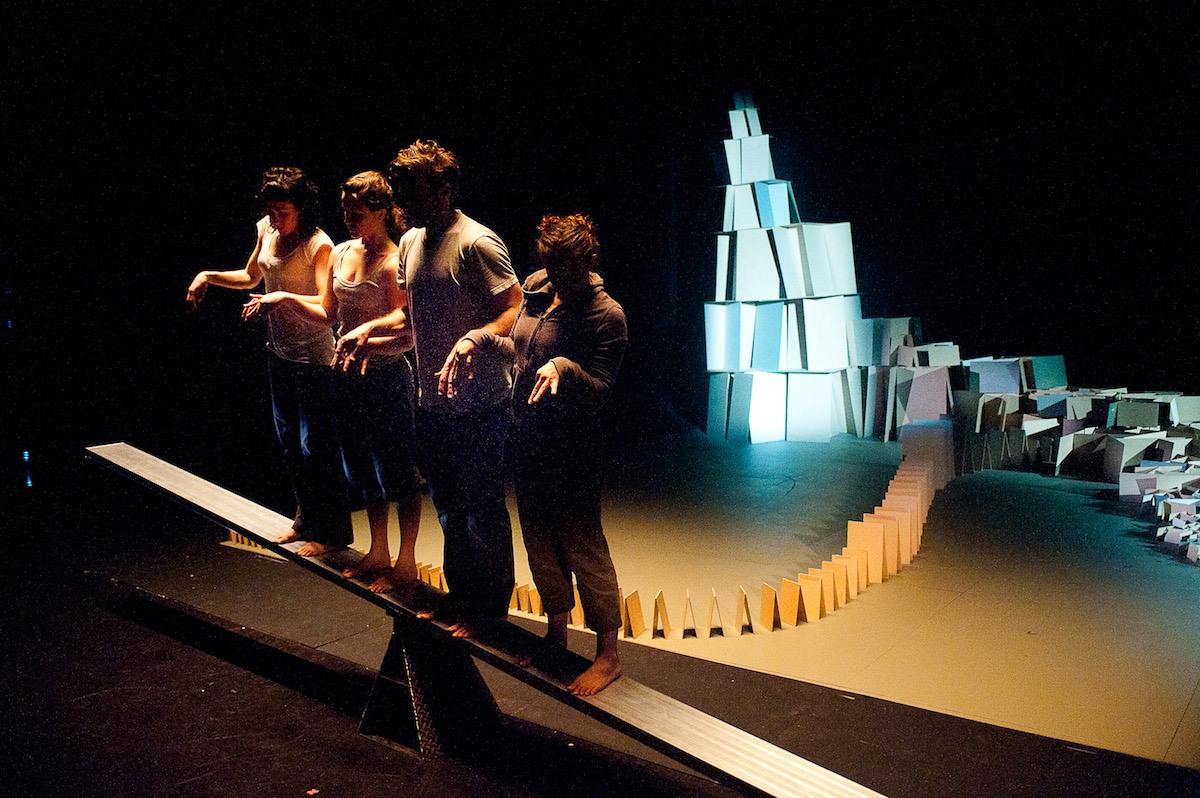

For choreographer Lucy Guerin, the theoretical connections between dance and architecture became much more tangible with the creation of Structure and Sadness, which was presented at the Pillow in 2010. Guerin’s inspiration for the evening-length work was the 1970 West Gate Bridge collapse in Melbourne, Australia. In this work, it’s not only about using bodies in the space to create meaning. The bodies here become the architects, building an actual structure onstage with plywood.

While Guerin started Structure and Sadness with pragmatic connections to concerns of the tasks of building, her work historically stems from a context of postmodern choreographic concerns. Starting in the 1960s in New York, choreographers like Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer began investigating everyday tasks and movements. Choreography explored the mechanics of the how of dancing, for a time putting aside the questions of “Why dance?” and “What does the dancing mean?” By the 1970s and ‘80s, choreographers such as Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane continued to delve into the action of dance, but began to layer in personal expression as well.

Originally from Adelaide, Guerin studied dance in Australia before moving to New York where she danced with choreographers including Tere O’Connor, Sara Rudner, and Bebe Miller. Her experience as a dancer in New York in the 1990s places her on a trajectory of American concert dance stemming from postmodern dance experiments in the early 1960s. At that time, choreographers shifted away from explorations of drama and character familiar from Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, toward simply exploring movement, often at its most mundane, most unskilled, and most pedestrian manifestation.

Since those early days, the dancing has gotten increasingly virtuosic—even if the choreographic commitment is to the ordinary. Guerin’s website announces this by stating: “The company is committed to the exploration of everyday events and the redefinition of the formal concerns of dance. New productions are generated through an experimental approach to creative process and may involve voice, video, sound, text and industrial design as well as Guerin’s lucid physical structures.”

Founding a Company

Guerin formed the Melbourne, Australia-based company Lucy Guerin, Inc. in 2002 with the express mission of creating and touring new dance works. Although Lucy Guerin, Inc. has only appeared at the Pillow once, her work was previously performed in 2005 by another Australian company, Chunky Move. Tense Dave, co-choreographed by Guerin and Chunky Move’s then artistic director Gideon Obarzanek, was a thrilling evening of dance theatre, darkly humorous and theatrical.

It, too, reckoned with architecture, as the whole work took place on a “revolve,” a large circular stage that spun continuously throughout the performance.

Australian dance writer Sophie Travers sees evidence of Guerin’s path in considering the scope of her choreography. She writes:

Guerin’s pedigree shows in work that is highly crafted, fascinated by choreography and eager to explore aspects of everyday behaviour inside abstract frameworks.

Guerin herself has said that as a choreographer, she finds that she is, “very interested in purity of form and in starting from a very clear, structural idea.”

How then does an interest in structure and form from a choreographic perspective turn into a much more literal definition of those terms? And why would Guerin shift from what she terms, “the exploration of everyday events” to a particular and not at all everyday moment in history?

When she began the initial investigation for the work that would result in Structure and Sadness, Guerin was thinking more generally and more abstractly. Her choreographic research focused on themes of collapse and disintegration. The more she researched, the more she was drawn to the challenge of the specificity of the incident. She remarked in an interview with dance writer Susan Reiter, “Generally, my work doesn’t connect to a real event, or any narrative storyline. So that was something I wanted to try and to see if I could [do] because it’s quite a difficult thing to represent in dance. I like to choose subjects which don’t render themselves easily in dance, because I think it pushes me in new directions.”Susan Reiter, ”The Joy in Sadness.” New York Press, September 23, 2009

The West Gate Bridge, linking inner city Melbourne to the western suburbs over the Yarra River, was constructed in a massive building project beginning in the late 1960s. In 1970, two years into construction, the span collapsed, falling to the ground and water. Thirty-five construction workers, some who were on a girder, some of whom on lunch break below, were killed. In the ensuing investigation, it was found that almost everyone was at fault, including bridge designers, engineers, and contractors. The Report of Royal Commission concluded after investigation: “Error begat error… and the events which led to the disaster moved with the inevitability of a Greek Tragedy.”

Guerin is by no means the first or last choreographer to make a dance inspired by content that is devastating, tragic, poignant, or just plain sad. Some of the masterpieces of 20th century dance stem not from places of joy but of trauma. Martha Graham’s iconic solo Lamentation (1930) was a response to the Spanish Civil War, while Paul Taylor’s Promethean Fire (2002) was made after September 11th. Dance masterpieces that contend with the legacy of the AIDS crisis include Lar Lubovitch’s Concerto Six Twenty Two (1986) and Ulysses Dove’s Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven (1993).

Interview with Guerin

Guerin talked about Structure and Sadness as it related to other dances in a PillowTalk titled “Responding Creatively to Tragedy.”

True to her roots as a postmodern choreographer, Guerin began to explore physical concepts from which she would build the movement vocabulary for the dance. For example, as she explained in an interview, the dancers worked with engineering principles of compression, suspension, torsion, and failure. However, once the scientific ideas were applied to human bodies, the work took on an emotional texture, even without thinking specifically about the West Gate Bridge. As Guerin said, “when you apply [these physical principles] to the human body, or two human bodies together, this emotional language comes up that parallels the experiences that were a result of that collapse.”

Structure and Sadness depends on a deep collaboration among a variety of participants, in the creative process and in performance. For the sound score, Guerin worked closely with composer Gerald Mair. The electronic music score incorporates real-life sounds, some from that day and some recorded underneath the existing West Gate Bridge. Part of the visual pleasure of this work comes from the contributions of the lighting designer and the projection designer. It’s remarkable that moments of beauty can come out of the contemplation of something absolutely not beautiful. And finally, and perhaps most noticeably, in performance, the performers act as set designers. Each night, the dancers build an intricate and delicate structure on stage.

Guerin commented: “The dancers spent an intense amount of time working out how to build this structure. I was really impressed by their focus and concentration. That was really an essential part of making the work. I wouldn’t have been able to do it without those particular dancers.”

This idea of building a structure on stage brings to mind a landmark duet by Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane from 1979 called Blauvelt Mountain, performed at the Pillow in 2002. In Body Against Body, Jones describes it as an abstract dance with a set: “The set was a simple brick wall about six feet at its highest point.” Together the two dancers constructed and deconstructed it onstage. Jones reflected on it, after performing it in Berlin, while the Berlin Wall was still intact.

He said: “One thing I’ve learned is that the world brings a great deal of baggage to each performance….The Germans went crazy over it. They read all sorts of things into it. They thought we were making statements about their society.”ed. Elizabeth Zimmer, Body Against Body: The Dance and Other Collaborations of Bill T. Jones & Arnie Zane, 1989 Jones’s comment suggests that no matter where Guerin started, audience members find their own references within the dance. Like Blauvelt Mountain, Structure and Sadness is not a narrative, or recounting of the events of that day in 1970. Rather it’s a meditation on the event and its resonance.

The movement of the dancers isn’t just about the set building. The dancers move fully, in solos and in groups, with partnerships that depend on balance and counterbalance. While partnering techniques may look familiar from postmodern work that builds on contact improvisation, here the interdependence takes on metaphoric meaning. Cool and precise, the dancers layer pieces of plywood. They know what they are doing; they can build this abstract structure. As the dancers partner with the materials, both symbolic and real, the simple acts unfold with a resonance of inevitability.

Guerin thinks that each performance of Structure and Sadness is “hugely demanding for [the dancers]. They’ve got this incredible focus and concentration on the building and then they have to drop that, switch completely when they’re dancing.”Reiter, New York Press.

We count on artists to help us make sense of all sorts of things, and Lucy Guerin knows this. Watching Structure and Sadness brings to mind a line from William Butler Yeats, which he wrote it in response to the Easter Rising in 1916, an Irish Rebellion against British rule. Yeats commented: “All changed, changed utterly: A terrible beauty is born.”

In its contemplation, in its specificity, and in its abstraction, Structure and Sadness connects us and compels us. Freighted with loss, it acknowledges humanity.

PUBLISHED March 2017