Introduction

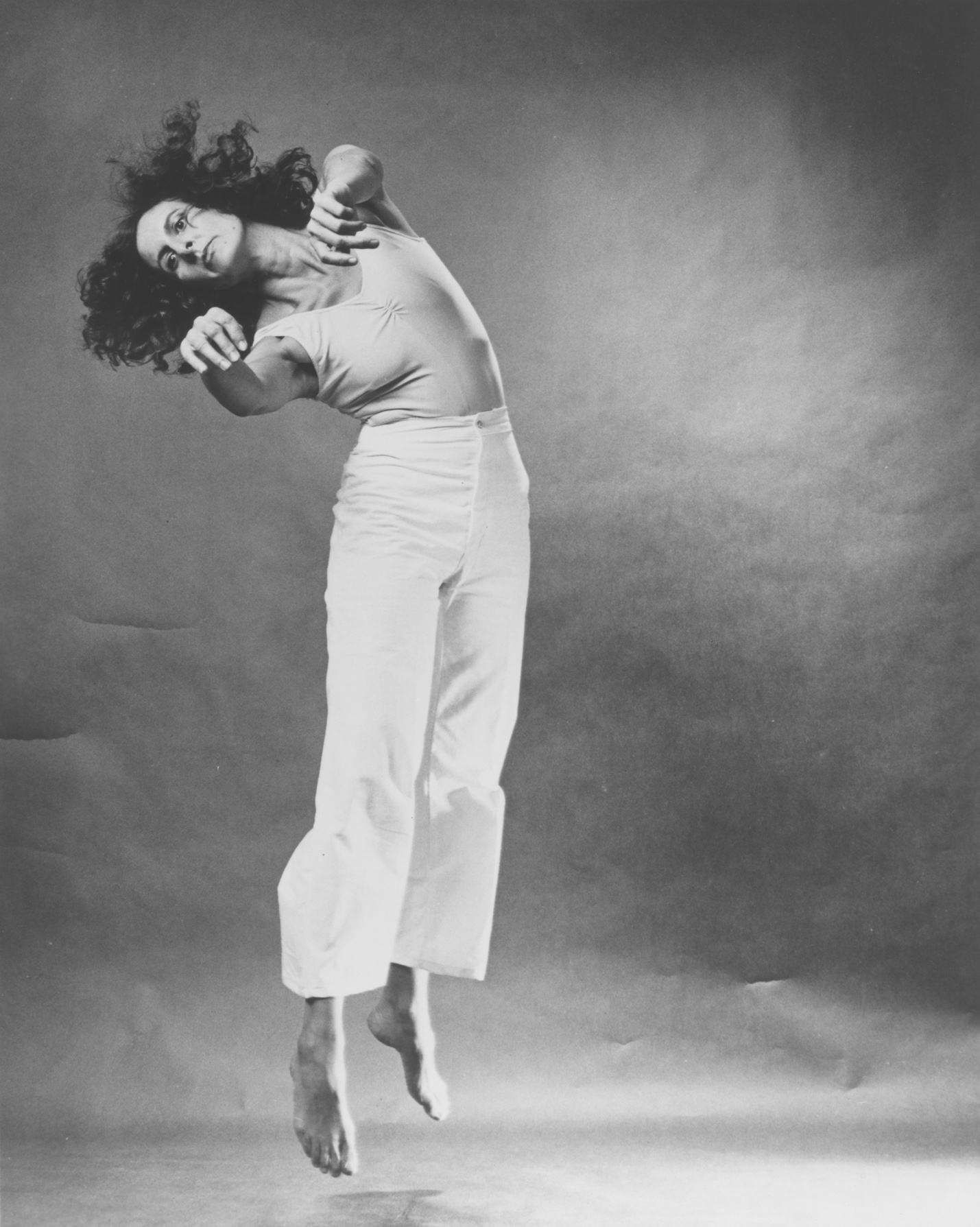

From the time she first arrived in New York in the early 1960s, Trisha Brown did nothing short of continuously refusing to let modern dance be defined. She became a leading participant in the shaping of investigations and innovations of postmodern dance in the United States. As a part of Judson Dance Theatre and in the later collaborative Grand Union, Brown and her contemporaries developed choreographic strategies almost taken for granted in present-day postmodern dancemaking. Throughout her choreographic career, she asked herself big questions as she made dances, and in answering them, her work probed uncharted choreographic terrain. What kinds of movement are appropriate for choreographic investigation? What are the relationships between mathematics and dancing? What meaning can be made with gestures? What happens when you talk while you dance? How can collaborations with artists from the worlds of music, visual art, and lighting enhance choreography? What is a logical sequence of movement events? And what happens when you interrupt that logic?

Brown sometimes made the path of her choreographic journeys visible to the audience; other times she merely let us witness the outcome. Over the years, she tested the traditional role for an audience for dance in different ways. She asked us to follow her and her dancers into gallery spaces as they danced along the walls and into the streets, to watch dancers walk down the sides of buildings. In her 1969 solo Yellow Belly, she asked us to yell at her from the audience, calling her names. In 1994, she asked us to watch her although she refused to meet our gaze. Throughout the entire solo, If You Couldn’t See Me, Brown kept her back to the audience.

Early Works

Brown’s pioneering works of the 1960s had scientific principles at their base rather than narratives or emotions; they were anti-expressive, coolly intellectual inquiries of movement. Like her contemporaries, Brown started in the early days of postmodern dance by stripping away the layers of expressivity and emotion evident in Martha Graham’s choreography, while simultaneously refusing to be seduced by the exquisite virtuosity of Merce Cunningham’s dancing. Her early choreography grappled with movement for the sake of movement. As she defined it in an interview from 1978,

Pure movement is movement that has no other connotations. It is not functional or pantomimic. Mechanical body actions like bending, straightening or rotating would qualify as pure movement providing the context was neutral.”

She went on to say: “All those soupy questions that arise in the process of selecting abstract movement according to the modern dance tradition—what, when, where and how—are solved in collaboration between choreographer and place. If you eliminate all those eccentric possibilities that the choreographic imagination can conjure and just have a person walk down an aisle, then you see the movement as an activity.”

Brown’s comment about eliminating the eccentric suggests an embrace of the ordinary. Her version of “ordinary” makes for some extraordinary dancing. She revisited an early solo more than 30 years after its premiere, when she re-staged her Homemade (1965) for Mikhail Baryshnikov as a part of the White Oak Dance Project’s PAST Forward (2000). Baryshnikov wriggled himself into the past with this piece, achieving a cool neutrality in his performance that shocked those who identified him with dramatic flourishes in balletic solos.

Accumulation with Talking Plus Watermotor is another solo choreographed and performed by Brown; in this one, she simultaneously moves and talks. Choreographed in 1978, its place in the historical trajectory of modern and postmodern dances creates a significant signpost from which to view the talking dancing which followed. The masterful solo combines different dances into a singular event. Accumulation exemplifies Brown’s early choreographic explorations in which she combined pedestrian movement with complicated structures and rules, while Watermotor demands more physical virtuosity from the dancer. As she moves through the different movement styles, Brown also talks, splicing in the telling of two different stories while never using the movement to illustrate the talking. The outcome of the intentionally fragmented action and storytelling is a stunning display. The solo demonstrates Brown’s appetite for movement, coupled with her witty intelligence.

Over the years, Brown used a wide palette of music for her dancemaking: from Laurie Anderson (Set and Reset, 1983), and Bob Dylan (Spanish Dance, 1973), to Bach (M.O., 1995) and Monteverdi. In 1998, after choreographing the Monteverdi opera L’Orfeo, Brown created Canto/Pianto, a danced-only version of the Orpheus story. Gone is the pure movement of other pieces; in Canto/Pianto Brown used dance in a way that is truly moving for the audience. Once again Brown found a way to use movement masterfully, showing that dance can tell a story in a different way from any other medium. The Orpheus story is danced with economy and passion, the meaning found solely in the movement itself. Brown removes the extraneous bits, leaving only the essence. With El Trilogy, Brown turned her attention to jazz music. As collaborators, composer Dave Douglas and Brown each decided to explore improvisation, both in the development of the material and in performance, as a launching-off point in this series of three works.

Set and Reset

Set and Reset owes its beginnings to the Pillow, as the initial artistic collaboration was supported by a sizable grant from the Massachusetts Council for the Arts, engineered by the Pillow. While it premiered at BAM’s Next Wave Festival, it has been performed several times at the Pillow. It is a luscious work, with costumes and set design by Robert Rauschenberg, one of several collaborations between the two artists. It’s not about big movements through blasting space; rather it’s about the smaller movements that propel the dancers in circles, arcs, and planes. It exhibits an understanding of the body that’s almost opposite from a balletic sensibility, with equivalent specificity.

The dancers never fulfill a static shape or pose; there is no visible preparation for movements; there is a sense of on-goingness that is mesmerizing. They swivel, roll, and curve. Set and Reset masterfully built on Brown’s early explorations of pedestrian movement, sped up and made more intricate. But it is performed with a sense of ease that is spectacular.

Final Rauschenberg Collaboration

Foray Forêt (1990) was Brown’s last collaboration with Robert Rauschenberg, who designed the costumes, sets, and lights. The ensemble piece shows her interest in intricacy and asymmetry, and her observation of the world around her. Things appear and disappear. Dancers dart on stage, they spill, they burst, they emerge. Solos, duets, and small groups show up and then dissolve.

As Brown continued to explore the innumerable possibilities of choreography, her questions deepened and she pushed the bodies of her dancers further and further to find solutions. Her choreographic structures got increasingly multifaceted and her movement style increasingly complex. Her investigations intrigued and inspired fellow choreographers, innumerable dancers, dance writers, and scholars of all sorts.

Seemingly effortless, the slippery, twisting bodies of her dancers seem at once weighted and floating. The dancers seize the space, emboldened with a physical intelligence and authority that both grounds them and sets them free. Brown’s work reminds us again and again that choreography is at its best and richest when body and mind work in concert to investigate the whys and wherefores of movement, structure, and space.

PUBLISHED August 2017