Early Influences

Jawole Zollar grew up in Kansas City, Missouri in a household where music was at the center of her family’s life. She and one of her sisters studied ballet for a brief period, after which she began studying with a different teacher, Joseph Stevenson, who was a former dancer in Katherine Dunham’s company. The Dunham technique laid a foundation for her continuing exploration of African-diaspora dance, and Stevenson also exposed his young students to different performance experiences that included appearing at nightclubs and in burlesque shows. In her later work, Zollar would often draw on these early experiences and embrace many different forms of dance expression as valuable material for her choreographic palette.

She continued her dance training at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, where she received her undergraduate degree and at Florida State University in Tallahassee, where she received her graduate degree. In 1980, Zollar took the next step in her professional development by moving to New York City, where she found an artistic home with dancer/choreographer Dianne McIntyre and her dance company Sounds in Motion. The two women were both interested in using African-American cultural elements as key components of their choreography, and this was especially true when it came to jazz music. Zollar had grown up with an appreciation for jazz in her family home. As dance historian Veta Goler describes the artist’s formative years, “At home, she listened to the records her parents played and developed a love of the singing of jazz vocalists Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Gloria Lynne, and of the music of Horace Silver, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Blakey, among others.”Veta Goler, Dancing Herself: Choreography, Autobiography, and the Expression of the Black Woman Self in the Work of Dianne McIntyre, Blondell Cummings, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar (Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 1994) pp. 145. Consequently, it was natural for her to embrace McIntyre’s use of jazz music and its improvisational structures as essentially an equal partner with dance movement. McIntyre was, in fact, in the process of developing an approach to her choreography in which jazz musicians and dancers worked simultaneously in the studio, improvising together in a symbiotic creative relationship.

Veta Goler also points out that in spite of their similar aesthetic leanings, Zollar didn’t feel entirely comfortable with McIntyre’s movement style and so only performed with her company sporadically. They were different body types, and there was a disjuncture in their kinesthetic approaches.Ibid., pp. 142-143. Perhaps this difference in personal movement styles was a contributing factor to Zollar’s decision to form her own company, Urban Bush Women, in 1984.

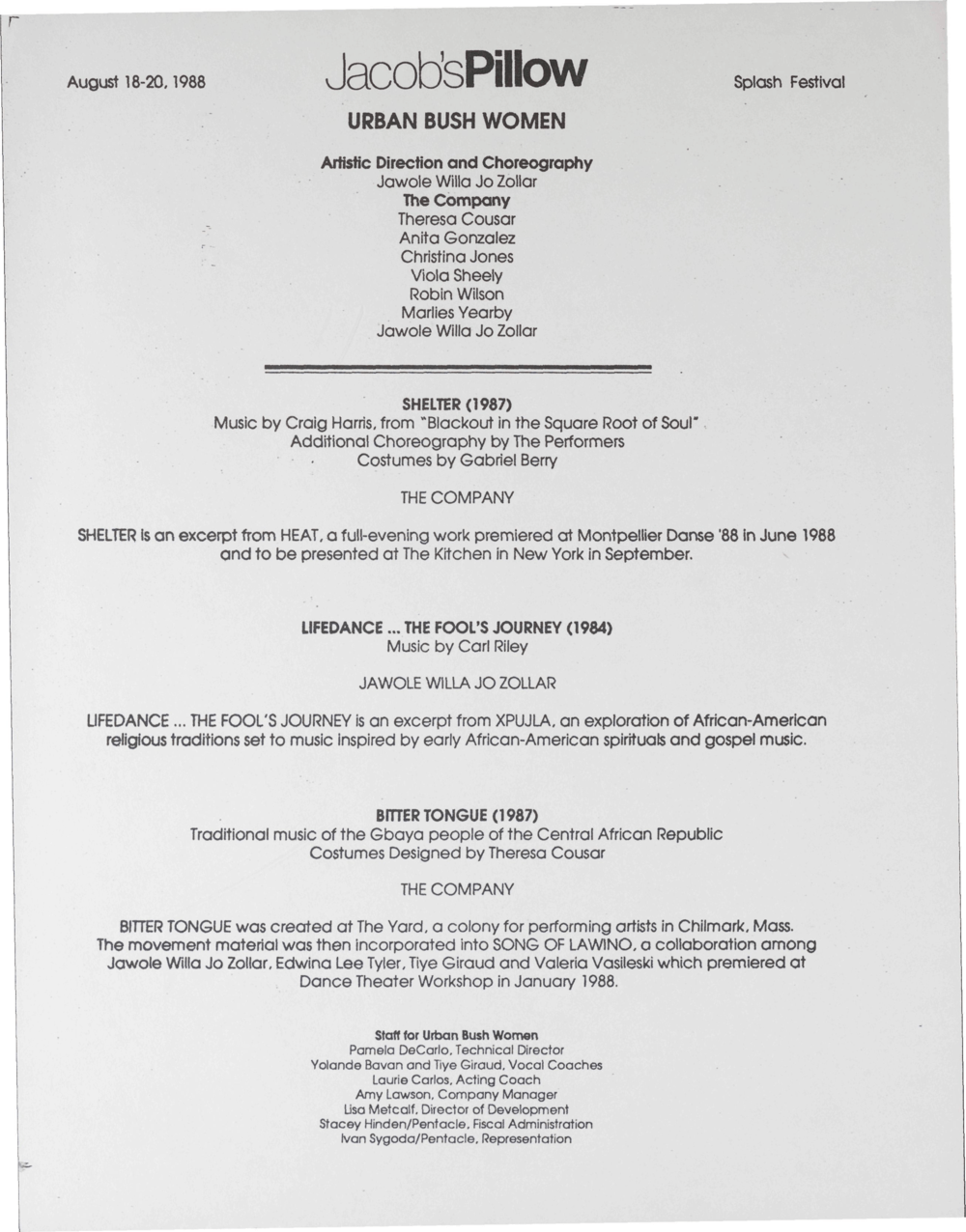

First Appearance at the Pillow 1988

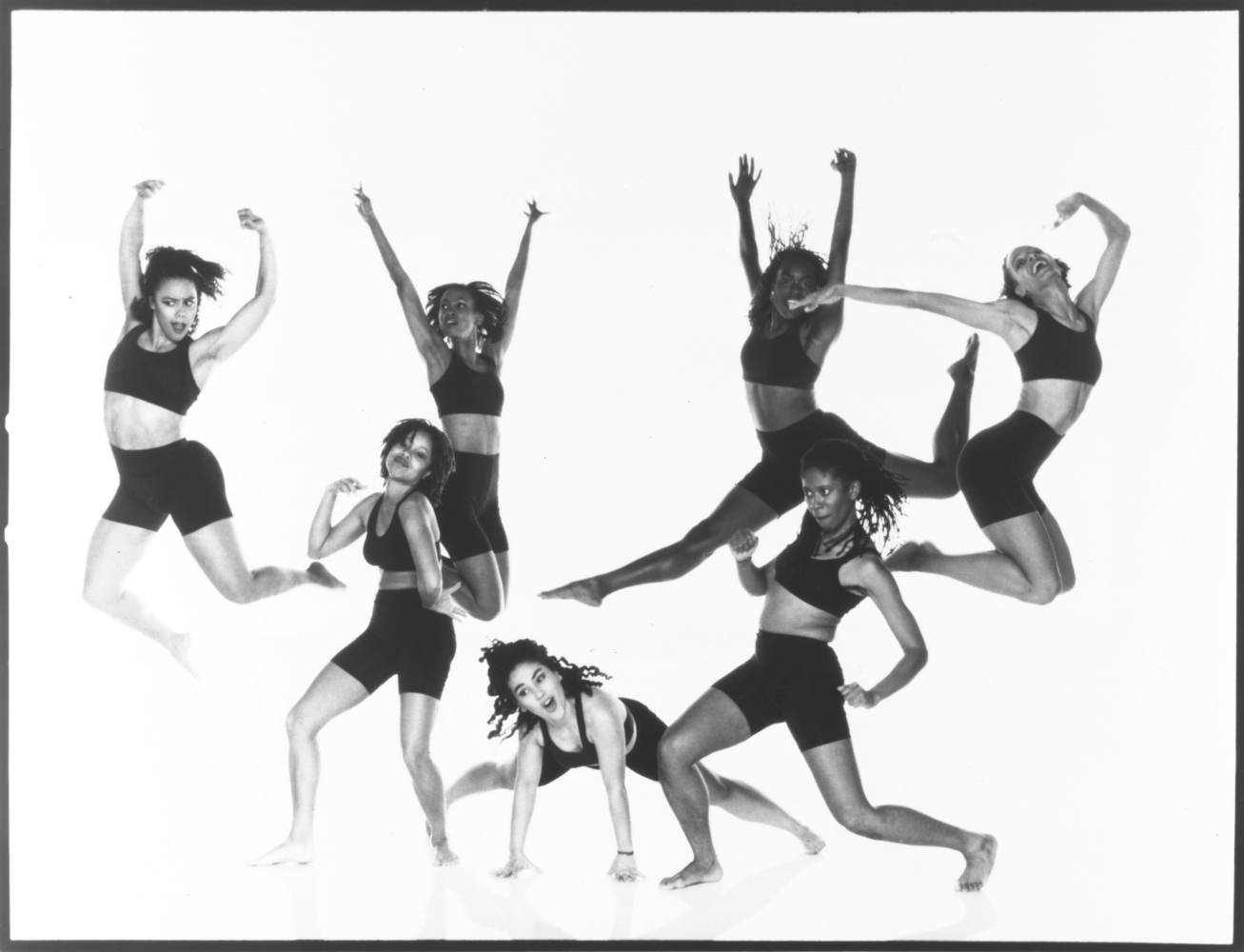

On August 18-20, 1988, four years after establishing her company, Zollar made the first of what would be many appearances at Jacob’s Pillow. Her company’s very first performance was on the Inside/Out stage, and it featured the three repertory works they brought to the festival.

The program opened with a solo for Zollar, The Fool’s Journey. It was a work that Zollar based on her exploration of the Tarot deck, the cards used in occult practices to divine the future. As dance historian Veta Goler explains,

Zollar states that in the Tarot the fool figure represents both the beginning and the end. The fool’s journey is what each person must do in his or her life to discover innocence and freedom.”Ibid., p. 157. The Fool’s Journey, the first LifeDance, conveys the development of a woman’s life from her youth to her old age. Zollar states that in the Tarot the fool figure represents both the beginning and the end. The fool’s journey is what each person must do in his or her life to discover innocence and freedom. The solo reflects Zollar’s belief that life is a spiritual journey, and whether our spiritual path intersects, parallels or substantially mirrors that of another, we must travel our journey alone.Veta Goler, Dancing Herself, p. 157.

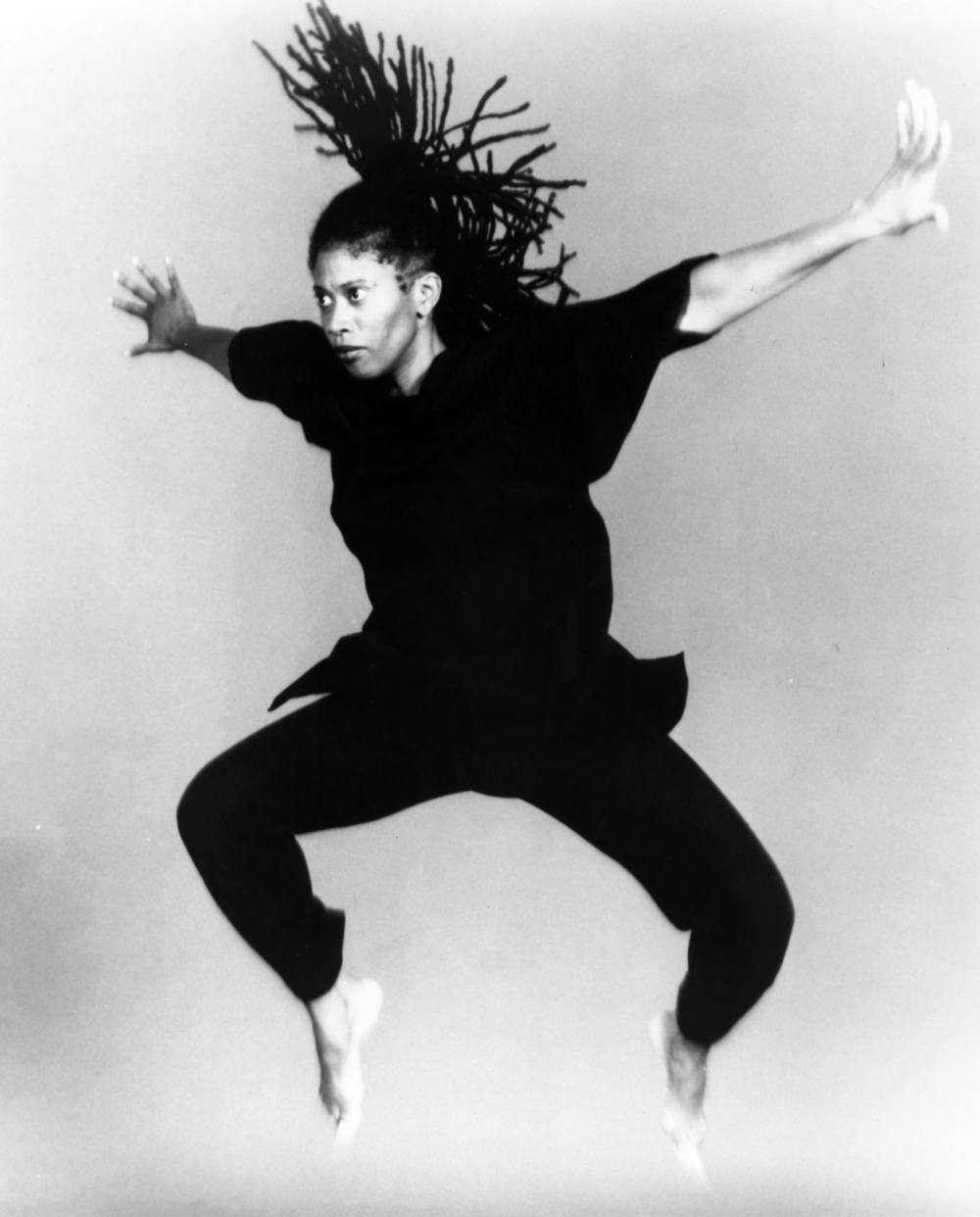

As one of her earliest works, The Fool’s Journey may be thought of as a metaphor for the artistic journey Zollar was setting out on, or as a kind of template for the aesthetic direction she was beginning to chart. In her exploration of movement material for herself and her company members, she began to establish several artistic signatures that would characterize their work. For example, she later described this early period in her career as a time when she was exploring movement that was “rough-hewn,” movement that was allowed to be severe and elemental, lacking superficial decoration.

She was fearlessly discarding the softness and lyricism that not only characterized balletic movement aesthetics, but that also informed the movement of pioneering artists like Ruth St. Denis. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, a student of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, Martha Graham, had undertaken a similar iconoclastic path by discarding the movement conventions of her predecessors. Particularly in Graham’s early works such as Revolt (1927) and Heretic (1929), there are moments of harshness and percussiveness that stake out new ground for contemporary concert dance.

Dance historian Deborah Jowitt explains some of the implications of choreographers’ aesthetic choices in her discussion of this early period of experimentation in American concert dance:

What ballet dancers sought to conceal—effort—modern dancers revealed. The floor wasn’t the grass of an imagined glade on which to gambol; it was a drumhead to strike and rebound from. It might be a trap. A leap didn’t express the soul’s transcendence or earthly passions; it represented a triumph of strength and daring, a hard-won soaring of the human spirit. Any distortion, angularity, or imbalance resulting from emotional verity or physical struggle was not only acknowledged, but affirmed.Deborah Jowitt, Time and the Dancing Image (New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1988), p. 167.As a testament to the cyclical nature of artistic innovation, an audience member at the Pillow during the summer of 1988 would have seen Zollar and her dancers affirming variations of some of the same things Jowitt speaks of. In The Fool’s Journey, for example, Zollar acknowledges the world that exists from the knees down. She enters walking—if one can call it that—in a crouch that requires her to have her legs bent double beneath her most of the time. (It also occurred to me that she is almost in a fetal position as she moves, an apt representation of human beginnings.) After a painfully slow progress in that position, she rises and performs a phrase of flailing, jagged movement, then sinks to the floor again to walk on her knees. She shifts between these low-level and high-level movements several times, as if she is testing some height-limitation placed on the space that she is permitted to use.

Zollar also uses simple costume additions and subtractions—a pair of bloused pants, a scarf, a shawl, a head wrap—to underscore the dance’s theme of journeying through the different phases of one’s life. The Fool of the Tarot deck is always depicted as a traveler carrying a bundle tied to a stick; and, for Zollar, the bundle holds her minimal costume changes. It is an effective theatrical device that speaks of the necessary—but limited—roles of earthly possessions. The forked stick she carries functions variously as a scepter, a tool, a divining rod, a staff to support her, and an oar that helps propel her on her journey to the afterlife.

As the dance unfolds, one becomes aware of another device Zollar uses, one that would come to distinguish the unique aesthetic of Urban Bush Women over the years—vocalization. As a transition between the different sections of her dance, Zollar uses a phrase, “Hey-ha-ha-ha,” that is a voiced as a panting exhalation, a kind of heavy breathing that punctuates each syllable; and, near the end of her solo she adds an eerie, bird-like cry to the phrase. Her vocalization, like her movement, is a minimalist element that speaks volumes about her subject matter.

In the next dance, Shelter, one can see the company’s evolving exploration of movement that privileges a downward emphasis. Whereas ballet technique emphasizes the bending of knees—the plié—as a connective element between steps or as a preparation for becoming airborne, dancers of the African diaspora frequently maintain a bent-kneed position throughout the entirety of a movement phrase. In other words, one stays in plié as a ground-base for performance, one lives at that level. Author Jacqui Malone refers to this position’s significance among black dancers when she mentions a slave song that intones dancers to “gimme de kneebone bent.”Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996), p. 11. She then goes on to say, “To many western and central Africans, flexed joints represented life and energy, while straightened hips, elbows, and knees epitomized rigidity and death. Ibid., pp. 11-12.

This dichotomy between the vertical aspirations of Western dance forms and the earthbound weightiness of dance forms that stem from Africa is one of the distinguishing factors that characterize the work of many African-American artists. Moreover, the contrast between the two can be used as a dynamic choreographic element. To further emphasize weight, the women in Shelter splat their bare feet against the floor and slap their hands against it when they fall. Effort is acknowledged in the sense that Jowitt speaks of it, but it is intensified to the point that the labored breathing of the dancers becomes an integral part of the dance’s sound score.

The movement and vocal elements seen and heard in The Fool’s Journey and in Shelter reach their peak in the performance of Bitter Tongue. If one refers again to Deborah Jowitt’s description of early modern dance innovations, one can see a parallel in the work of Urban Bush Women, because they literally play the stage like a drumhead. The Inside/Out stage at the Pillow is a raised platform without a compacted foundation beneath it, making it resound even more than a traditional stage.

In Bitter Tongue, the dancers increase the range of vocal material that was explored in the other two dances. Their guttural voices shout a line—“My Husband’s Tongue is Bitter!”—from which the dance derives its title. The words come from a long poem by Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek, Song of Lawino, which is a stinging commentary on the effect of Westernization on traditional African life. It tells the story of a wife’s complaints about the abusive way her husband treats her, after he has been away to be educated in the West. When he returns to his native land he constantly denigrates his wife and every aspect of the traditional culture he was born into—the food, the ways of dressing, the dancing, anything that speaks of non-Western ways.

Zollar’s choice of the poem as inspiration for Bitter Tongue reflects her wide-ranging interest in source material that takes a penetrating look at the oppressive conditions women of color endure around the world. As a recurrent theme in several of her works, this examination of women’s lives lays bare the psychological, emotional, and physical pain that is often buried beneath patriarchal fabrications of normalcy. The “rough-hewn” nature of her movement in a dance such as Bitter Tongue becomes an analogue for combating insufferable conditions which women have endured for too long. And, in this sense, the dancers—moving from passivity to strength—function as a band of zealots who present a united front. There is a communal strength that resonates throughout many of Zollar’s dances. It is something that creates stunning moments of group dancing, and it is also something that is cultivated from the very beginning of her working process.

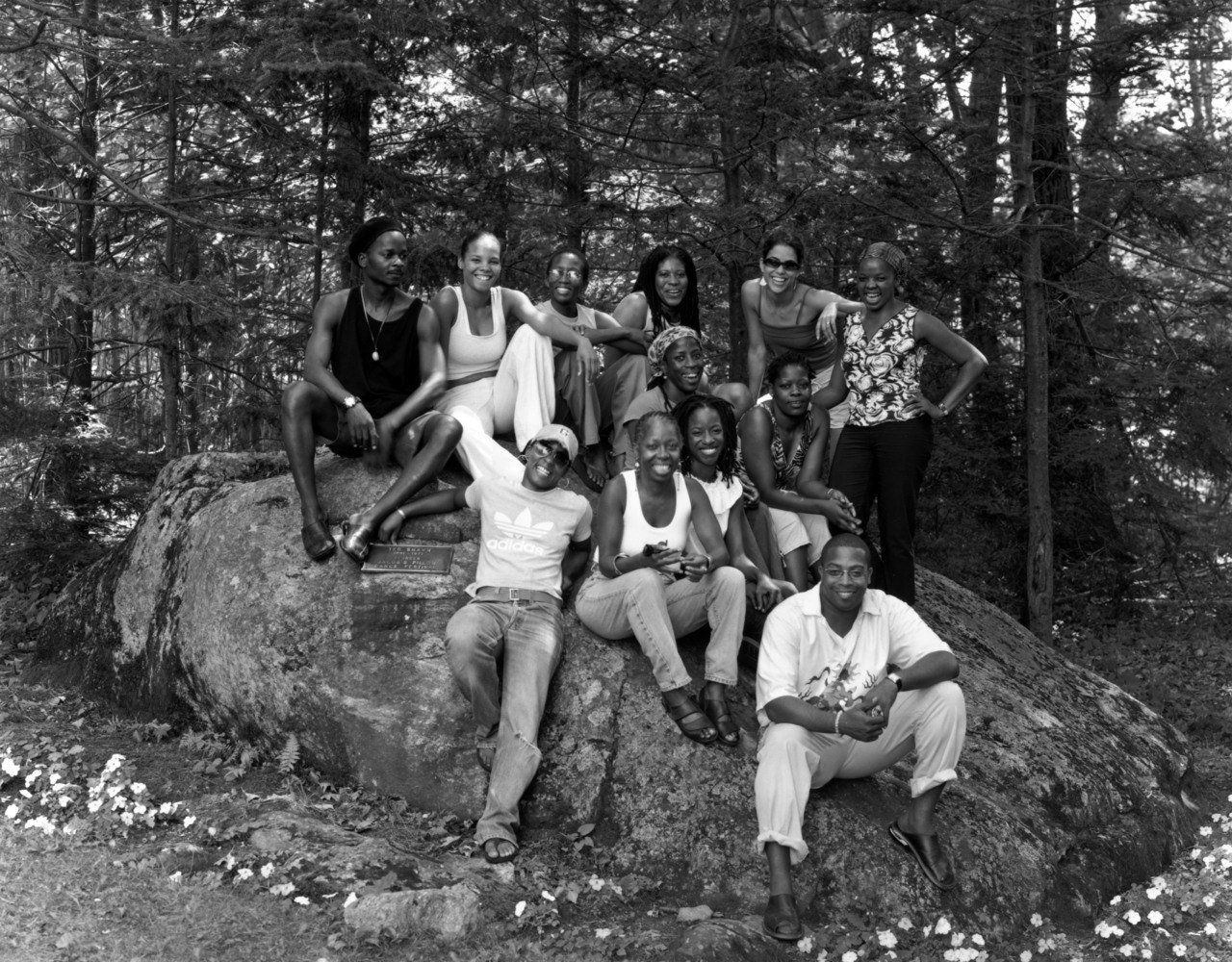

Zollar’s method of using group explorations of her subject matter in the early stages of her rehearsals, and her use of contributions from individual dancers in the making of a work, bespeaks the idea that art can be approached as a communal project. As director/choreographer, she is the final shaper of her work, but the lived experiences of sharing personal points of view and individual movement preferences during workshop sessions, underscores the communal nature of her company ethos. It is again Veta Goler who makes the connections between this creative approach that takes place in the studio and the lives of black women in the larger world: “Historically, black women have always established ways of coming together for mutual benefit. From the female networks in the family compounds of traditional African societies to the club movement and extended families of the New World, black women have supported and affirmed each other.”Veta Goler, Dancing Herself, p. 167. In this sense, when Zollar first came to the Pillow, she was in the process of building a unique sociocultural microcosm—exclusively for women of color—that centered on her dance company.

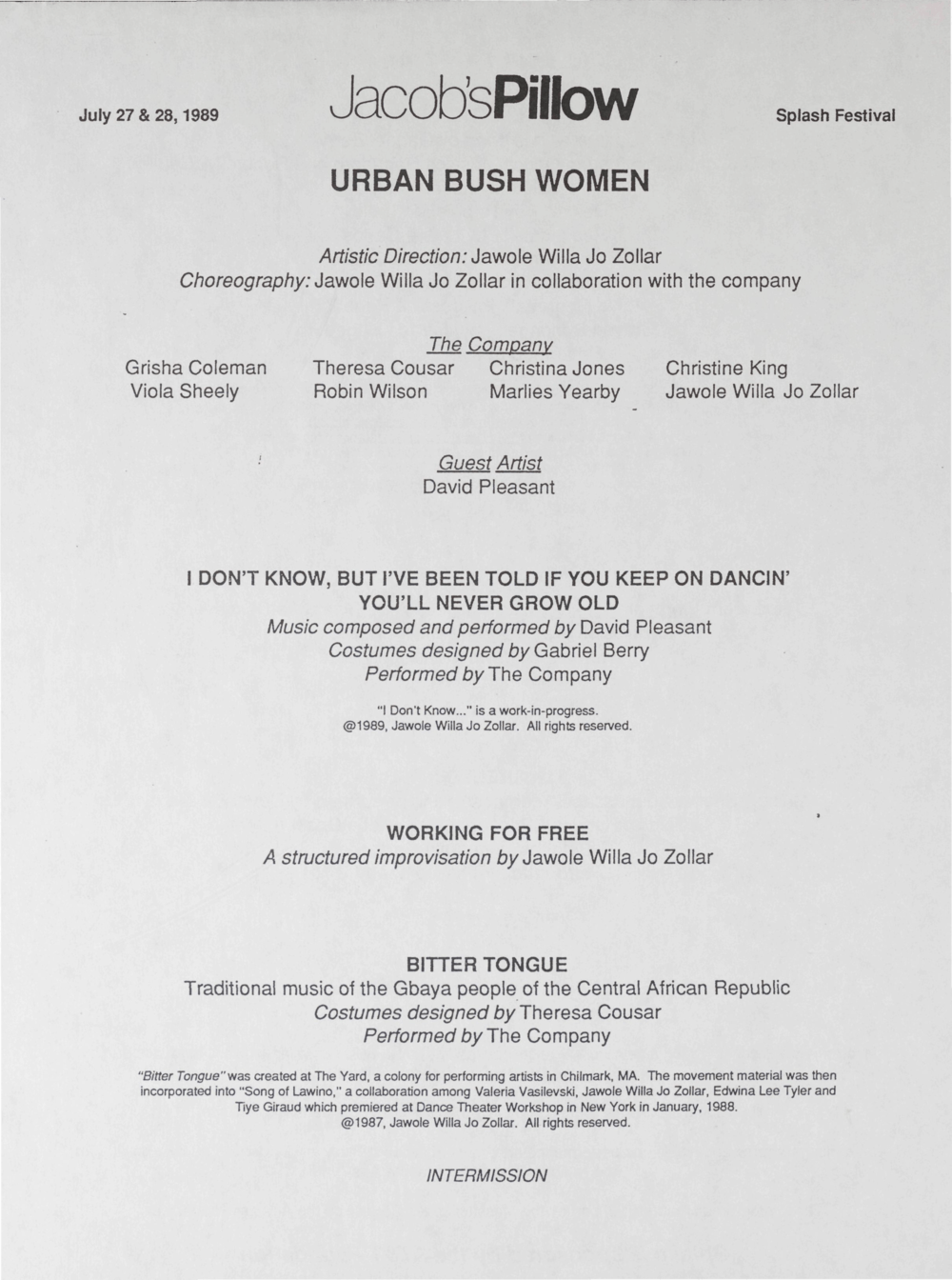

Second Visit to the Pillow 1989

Urban Bush Women returned to the Pillow the following year for performances on July 27 and July 28. They presented several new works, the first of which had the intriguing title, I Don’t Know, But I’ve Been Told, If You Keep on Dancin’ You’ll Never Grow Old.

Zollar opened the concert with an explanation of what inspired the work:

This piece grew out of a conversation with some funders and policy makers in dance who were lamenting over the fact that they thought there was not very much dance available in public schools. And, I disagreed very much with that statement. I think there’s a lot of dance available in public schools, but I think there’s a failure on our part to honor these forms. So this piece is dedicated to majorettes, drill teams, double-dutch jumpers, people who dance in bars, people who dance on the streets, people who keep the spirit of dance alive all over the world. Video of Urban Bush Women performance, July 27, 1989 (Identifier 295), Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

She set the scene with this explanation of one of the key components of her dance aesthetic: She has an egalitarian embrace of movement from vernacular dance and other sources, including forms that are traditionally not even thought of as being appropriate for the concert dance stage.

True to her word, the opening sequence of I Don’t Know is a rich amalgam of marching, handclapping, bits and pieces of vernacular dance, and raucous shouting that the dancers use to urge each other on. Zollar—playing a bass drum—along with her percussionist, David Pleasant, help drive the action forward, and they also engage in their own rhythmic movement. The scene can be thought of as a secular counterpart to what Jacqui Malone describes as occurring when Yoruba master drummers determine the dancers’ steps and patterns in religious ceremonies. Malone says, “In these settings, the dancing is symbolic and ordered and timing and body placement must be exact. Here the musician is the dancer is the musician. . . . In western Africa, a good drummer is a good dancer and a good dancer is a good drummer, ‘although the degree of specialty and professionalism varies with each individual.’”Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues, p. 14.

The next new work Zollar introduced to Pillow audiences on her second visit was titled Working for Free (A Structured Improvisation). As the title makes clear, this work was an improvisational solo. It allowed her to explore her personal movement style, and she also spoke, sang, and used gestures to create a humorous portrait of herself. She briefly incorporated autobiographical information about growing up in Kansas City, including references to the racial dichotomies she experienced there. The second half of Working for Free consisted of Zollar improvising based on suggestions from the audience.

Lipstick, which was also new to the company repertoire, began with an exploration of rituals of femininity as reflected in adolescent practices like the use of lipstick; but it also incorporated a story of a girl growing up in a harsh environment, so there was a deft interplay between humor and pathos. In addition, the piece reflected Zollar’s expanding use of spoken material as an integral part of her innovative dance theater, as the performers spoke, sang, and moved in seamless simultaneity.

Bitter Tongue and Shelter were reprised from UBW’s prior visit to the Pillow, and it is interesting to note the changes that had occurred in the works in the intervening year. The most noticeable change was in Shelter, where Zollar used a convention she would employ in several of her dances over the coming years. She would speak—either live or recorded—as part of the sound score, while her company members performed. In this instance, she sat stage-left, next to David Pleasant. This new element contributed to a more detailed narrative than could be achieved through movement alone:

Last winter, I was working this temp job—on the exclusive Upper East Side of New York City—that lasted for several months. On my way to and from work (every day) I walked past a black woman, who, in spite of sub-zero ice and snow, was living on the street. A brown-skinned thirty or fortyish woman with a strong handsome face and a thick head of hair, she lived on top of a square of cardboard, and she never asked me for money. Sometimes she would accept donations, and sometimes she wouldn’t. At my temp job, people called her “crazy,”—especially on really cold days—and said something should be done. . . . I couldn’t bring myself to walk by her and not offer her something, because her silent staring presence was palpable, and I could see myself in her. I could see myself taking a wrong turn and falling down, down, down. . . . being without income too long, losing my apartment. . . . I could see myself ending up between a rock and a hard place, at the intersection of reduced resources and reverberating rage. Video of Urban Bush Women performance, July 27, 1989 (Identifier 295), Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

As the monologue unfolded, Zollar’s delivery reflected the increasing desperation that she felt, as she empathized with the homeless woman’s situation. The dancers also mirrored that dynamic, as their movement built to a crescendo of explosive energy toward the end, accompanied by Pleasant’s shouts. Zollar’s final monologue reflected her growing concerns that radiated from the microcosm of a single homeless person to the macrocosm of the planet.

Shelter has remained in Urban Bush Women’s active repertoire to the present day, and it has continued to change over the years. It has also been set on other companies and for performances by university students. It has, for example, been performed by the women of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; but I have found the most riveting performance to be that of an all-male cast from the Ailey company. Without getting into a debate about the differences between male and female performers, and at the risk of bordering on gender insensitivity, I simply found that the all-male version took the climactic sequences of the dance to an “over-the-top” level that seemed to best fulfill the dance’s intention of creating images of complete desperation through the use of what appeared to be almost-uncontrollable, manic energy.

Third Visit to the Pillow 1990

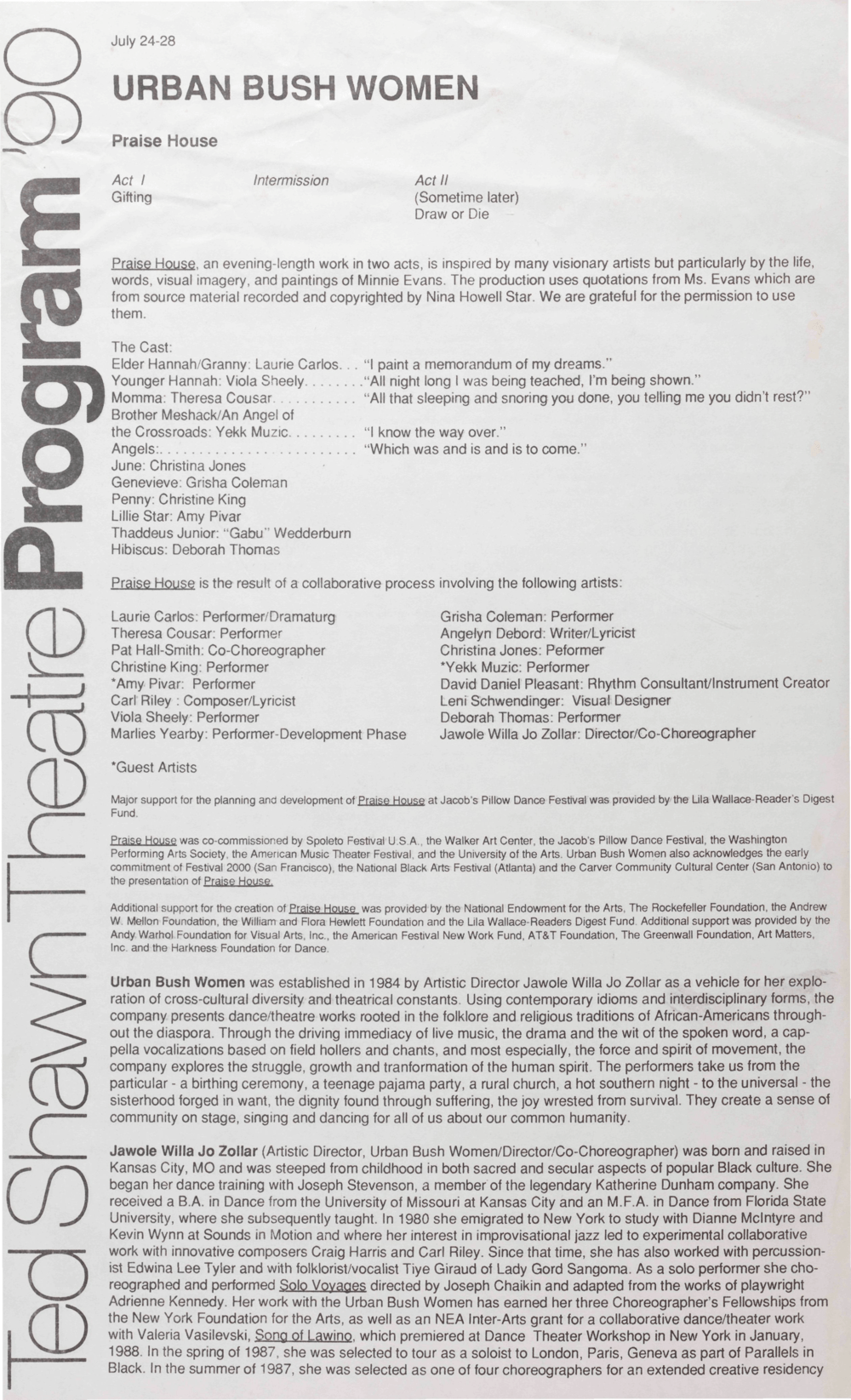

On Urban Bush Women’s third visit to Jacob’s Pillow, July 24-28, 1990, it seems that the very nature of their work was on a steep upward trajectory in terms of the elaborateness of the production, Zollar’s expanding artistic vision, and the ambitiousness of the project. For that visit, they presented Praise House, an evening-length work that was a full-blown musical theater production. It included a script written by Angelyn DeBord, who also shared credits for the lyrics of the production’s beautiful songs. Carl Riley wrote the music and also contributed to the lyrics. The cast included two male performers, “Gabu” Wedderburn and Yekk Muzic. Program, Ted Shawn Theatre, Program ’90—Urban Bush Women—Praise House.

Veta Goler states that Praise House was inspired in part by a four-hour, revivalist church service Zollar had attended.Veta Goler, Dancing Herself, p. 199.As noted in the program for the Pillow performance, Zollar also said she was inspired by her fascination with the artistic journey of the African-American visual artist, Minnie Evans.Program, Ted Shawn Theatre, Program ’90—Urban Bush Women—Praise House. Evans was born in Long Creek, North Carolina in 1892; and, with no formal training in the visual arts, she began creating her first drawings in 1935. By the mid-1960s, she began to gain recognition as a folk artist after she was discovered by a graduate art student, Nina Howell Starr, who began to show Evans’s work to the world by arranging exhibits.Douglas C. McGill, “Minnie Evans, 95, Folk Painter Noted For Visionary Work, New York Times, December 19, 1987.

Evans was considered to be a “visionary artist,” because she began her earliest drawings when she heard a voice that told her, “Draw or die.” She accredited all of her consequent artistic work to divine inspiration, visions, and the voices in her head. As art historian Reginia A. Perry describes Evans’s work,

The paintings and colored drawings of Minnie Evans are surrealistic without intellectualism or self-consciousness. They are works of a visionary who equated God with nature, color with His divine presence, and dreams and visions with reality. The world as revealed through Evans’ psychic revelations is a sacred province of complex visionary forms, angels, demons, hybrid plants, animals, and the all-seeing eye of God. Reginia A. Perry, Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992), n.p. Accessed at http://americanart.si.edu/search/artist-bio.cfm.

Based on the ecstatic fullness of African-American and African diaspora religious traditions and the fantastic visions of an artist possessed by God, Zollar’s Praise House brought a unique experience to Jacob’s Pillow audiences.

When the lights came up on the stage of the Ted Shawn Theatre, one immediately sensed the folk-art connections involved in the work. In a review of an earlier performance of Praise House at the Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston, South Carolina, dance critic Jennifer Dunning alluded to the atmosphere the stage set created:

Leni Schwendinger’s set is strung with lines of mundane laundry, from colorful human clothes to gauzy tablecloths that serve as angelic shawls. Two umbrella-like structures, which serve as gathering and resting places, are studded with found objects that make the structures look like visionary folk art—James Hampton’s “Throne of the Third Heaven” springs to mind, as well as the gentler paintings of Minnie Evans and Sister Gertrude Morgan. Jennifer Dunning, “Choreography Practiced as Anthropology,” New York Times, June 5, 1990.

The cast members slowly enter into the barely-lit space, as if they are, indeed, entering a praise house. Black communities in the South had small churches that were called praise houses. They were most often sparse wooden building with few amenities or decorative elements, but they provided a sacred space where members could gather to engage in the ritual celebration of their religious beliefs. The power of praise houses came from the spiritual vortex that could be created within them. The open space of their interior accommodated the worshippers who circulated around the floor. Early in Praise House, we see a circular, counter-clockwise dance in which the cast shuffles, stomps, and shouts to summon the spirit. Theater historian Anita Gonzalez—who is also a former company member of Urban Bush Women—addresses the central role that music and dance play in black community churches in the South:

Within African American church rituals, music and dance are used to connect worshipers to one another, to raise the emotions, and to punctuate moments of ecstasy. The sound and timbre of the voices create a harmonic resonance that moves through the congregation. Often the vibration of the voices become kinesthetic responses that result in physical leaps, shivers, or arm raising. A musical theater play like Praise House recreates the language and rhythmic patterns of the church service in both form and content. The musical themes are drawn from a repertory of rural revivalist chants and songs; while at the same time, the action of the play is advanced by musical transitions that are enhanced renditions of soul-stirring gospel music. Anita Gonzalez, “Jawole Zollar’s Praise House and the Ecstasy of Black Church Ritual, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, (Spring, 2004), p. 126. Accessed at https://journals.ku.edu/index.php.

The Ring Shout that the dancers perform is a black tradition that echoes other African-diaspora ritual dances. In its shape and its fervor, the opening dance in Praise House is similar to Jean-Léon Destiné’s voudun ritual dances that had been performed on the same stage years earlier. To trace the connections between African-American cultural practices and their diasporic antecedents, was, of course, a part of Zollar’s intention. It was one of the most important components of her aesthetic.

Angelyn DeBord’s script tells the story of a young girl, Hannah, her grandmother, Granny, and her mother, Momma; three generations of black women living with the complications stemming from the fact that the oldest and the youngest of them are gifted with otherworldly visions. Caught in the middle, the mother constantly complains about the bond between the daughter and the grandmother and their banter about the phenomena they see. They often discuss the angels they encounter on a daily basis. Those are represented by the six dancers who hover around them. There is pathos in the complaints of the mother and also in Hannah and her grandmother’s realization that they are often confused, because they don’t always understand their visions. But, there is also humor, as when Hannah holds forth about “angels’ toenails.”

Musician/actor Yekk Muzik portrays two other central characters, Brother Meshack and An Angel of the Crossroads. His characters weave in and out of the narrative, as he strums his guitar and sings. His two mythic figures function in scenes such as the transition of Granny from life to afterlife, where he sings I Know the Way Over. The first act ends with a haunting dirge and a processional that could be either a funeral march to the praise house or from it. The solemn singing and haunting harmonies underscore a wonderful and powerful conclusion to the scene.

The second and final act picks up with the theme of Momma’s laments about the burden of having a daughter who has been gifted with visions from another realm. Moreover, she sees Hannah’s power not as a gift, but as a dark phenomenon that keeps both of their lives in chaos. The grandmother, played by Laurie Carlos, continues to maintain a spiritual presence in their lives, even after death. Carlos voices her—and Minnie Evans’s—reflections on the role that drawing has played in her life. As Anita Gonzalez states, “[T]hese drawings are the spiritual path towards self-realization. The message that Zollar communicates is that art has a healing power, a power available to even the most unlikely of the Black community. The themes of folk, community, healing, and transformation propel the story.”Ibid., p. 124.

But, for Hannah, the self-realization of her exceptional spiritual powers continues to be a struggle. In one climactic scene, her distraction about the situation comes to the fore, as she sweeps the floor with a broom. The manic energy she displays while engaged in the task shows how she is caught between her mother’s demands that she attends to her “real world” chores, and the demands of the angels who constantly beckon her to join them. They seem to taunt and tease her; Gonzalez describes them as, “naughty uncontrollable dancers with childlike qualities who distract her and urge her to run away.”Ibid., p. 127

Praise House ends with a transformation scene, a kind of baptism that lets us know that Hannah finally accepts her extraordinary gifts, as the spirit of the grandmother intones, “Draw or die! Draw or die.”

Jawole Zollar and her Urban Bush Women have returned to the Pillow many times to perform works that continue to delineate their exceptional artistic visions. They have also used the Pillow’s facilities for residencies during which they could give full attention to their creative process. Ted Shawn had used the Pillow for the same purpose, and he had foreseen that the festival would continue to serve as that kind of retreat in years to come.

Zollar’s work has given Pillow audiences, students, and fellow artists at the festival an opportunity to become aware of the deep inner-workings of what it means to be a woman of color. Members of the Pillow community have been able to see the joy and pain of black people, and they have also witnessed artists perform whose political and social consciousness is indelibly written on their bodies. Moreover, it is etched in their bodies, because that “rough-hewn” movement that those artists perform emanates from muscles, tendons, and bones composed of the belief systems that lie within them.

PUBLISHED April 2017