Introduction

In his 2017 TED talk titled Can Art Amend History, visual artist and historian Titus Kaphar posits, “Can how we view art reflect the way we interact with the Constitution?” Kaphar goes on to dissect how in the United States legal system, when we want to change a constitutional law, we don’t erase the parts we wish to change. When amending the Constitution, we place these new laws next to the old. “In this way we can say, essentially, this is where we were, and this is where we are, and this is where we are going,” he states. As a painter, Kaphar activates historical works by bringing black and brown people into the foreground… We need this type of lens when discussing dance history.Kaphar explores this in his own work by reconfiguring and regenerating art history to include the African American subject. As a painter, he activates historical works by bringing black and brown people into the foreground, making them the subject of the viewer’s gaze rather than the white characters in a scene, for example. It occurred to me that we need this type of lens when discussing dance history. As a queer, cis-gendered white women, I am critical of our systems and also understand the bias and blind spots of my education and societal upbringing. This piece therefore is intended to speak to all, but is aimed more toward white folks understanding our need for self-examination, rather than justifying what black and brown people already know to be true and are hurt by every day.

With this in mind, I invite us to consider how dance, dance historians, and students, as well as an institution like Jacob’s Pillow, might address Kaphar’s challenge—juxtaposing the new with the historic, extending an invitation to sit with both inspiration and discomfort, engaging with where we were, where we are, and where we wish [and need] to go. The following is structured as a study—attempting to dissect and perform complex explorations, working on both sides of ideas, while pushing farther, adding new variables and ending with a slow, walk off stage, rather than a definitive crescendo. It is meant to be a small vignette in an ongoing dialogue.

Context

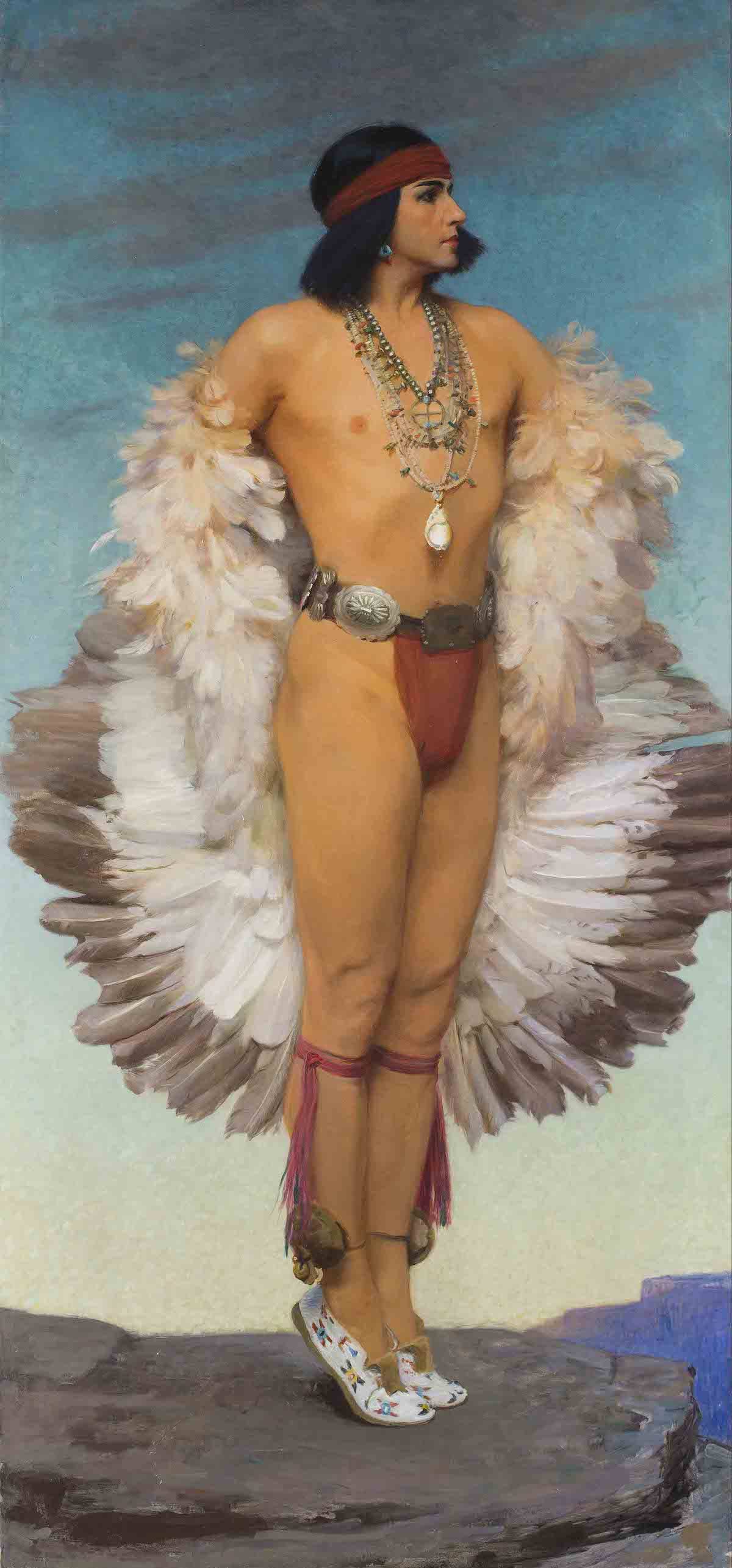

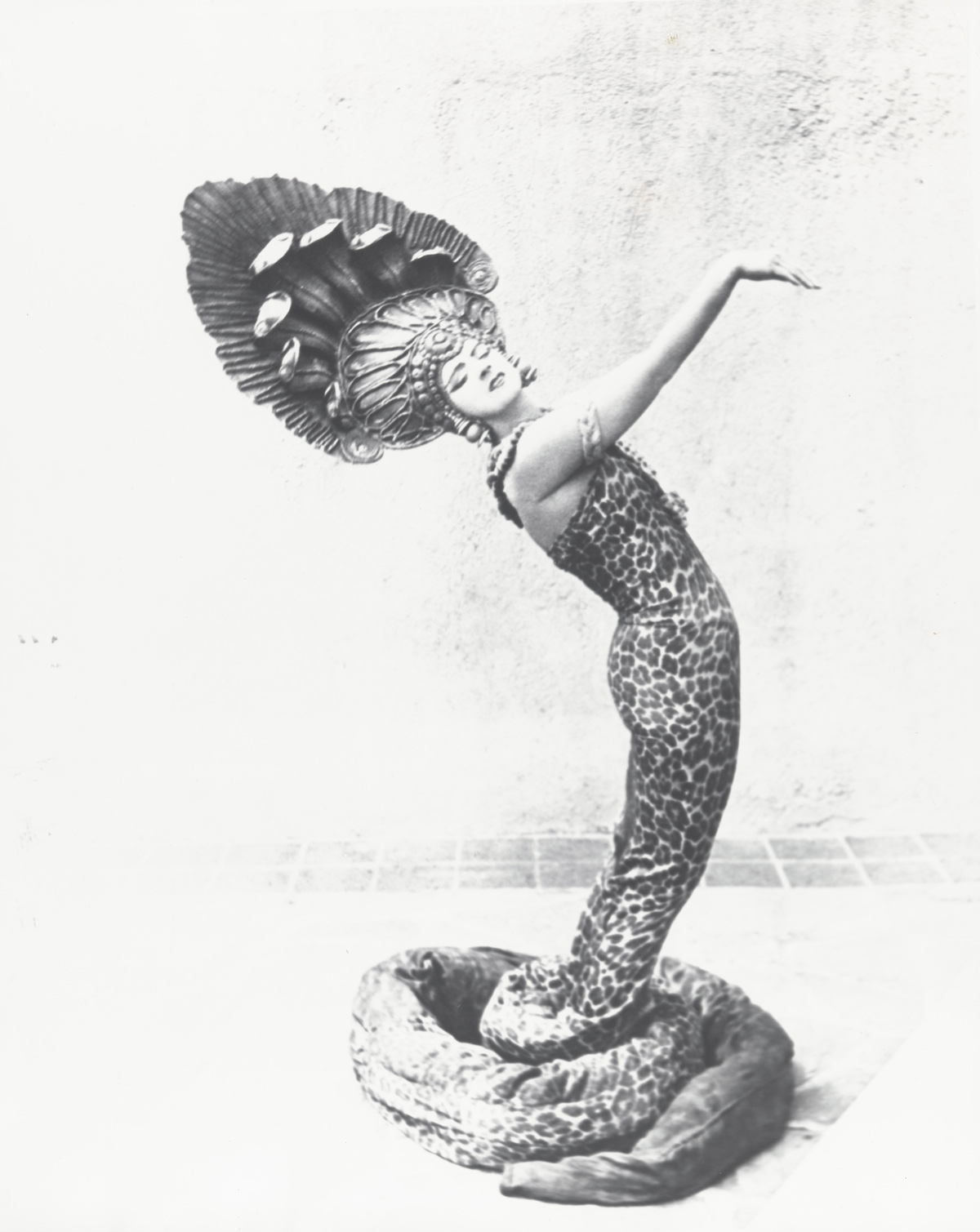

On either side of the stage in Jacob’s Pillow’s Ted Shawn Theatre, the first theater in the United States built specifically for dance, hang two 1925 portraits by Albert Herter: Ted Shawn to the left, costumed for his Hopi Indian Eagle Dance, and Ruth St. Denis to the right, costumed as Kwannon, the Japanese Goddess of Mercy. In recent years, interns arrive at the Pillow each summer and inevitably someone points to these portraits in outrage, wondering why these representations of cultural appropriation are allowed to hang in the theater. Their reaction is understandable when these artifacts are viewed through the lens of today and not placed in their historical frames and context. We must look at the social constructs and limitations at play in the 1910s and 1920s when Denishawn, a company of Euro-descendant dancers, was creating and touring works in which they presented dances from non-white cultural traditions. By today’s standards, these dances would be considered horribly disrespectful, but at the time, they exposed white audiences to movement inspired by non-Eurocentric dance styles. We must do this not to excuse them, but to contextualize and more fully understand these dances and artifacts along with deeper issues still at play in the field and the broader society.

In 1931, when Shawn first arrived at Jacob’s Pillow, the American stage was still home to white performers, fairly exclusively—minstrelsy having just ceased its reign as the national form of theatrical entertainment (around 1910). Black and brown people, let alone their dances, were not yet permitted in concert halls. Concertgoers were white, mostly upper-class people. This historical perspective does not lessen the fact that things should have been different; the fact is they were not. Additionally, we must not discount the amazing black art performed in the clubs and stages of enclaves like Harlem in New York, the Shaw neighborhood in Washington DC, ‘Black Wall Street’ in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Bronzeville in Chicago. But segregation was still widely practiced, and dance and theater companies, even through the 1960s and 1970s, had difficulty touring with non-white company members.

It’s important to consider the upper class’s societal leaning toward “oriental exoticism” coupled with spiritual mysticism—a trend among monied socialites to look to the Far East and to the occult seeking aesthetic and intellectual stimulation in the late 1800s and early to mid 1900s. Influencers of the time like Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Woodrow Wilson openly shared their yoga practices and embraced and heightened the elite, educated interest in physical exploration of Eastern forms. Of course, the arts and artists relied heavily upon the affluent for funding and performance opportunities. We cannot discount the alignment of avant garde tastemakers like the wealthy heiress Mabel Dodge, who very publicly courted and, in 1923, married Tony Luhan, a full-blooded Native American man. Dodge facilitated and financed both American and European visual artists, writers, and performing artists and is a quintessential example of the counterculture—in both society and the arts that grew intertwined and interdependent on one another. In her book, Utopian Vistas: The Mabel Dodge Luhan House and the American Counterculture, author Lois Palken Rudnick describes how an article written by Mabel Luhan, titled “A Bridge Between Cultures” in the publication Theatre Arts and read by Martha Graham led to Graham traveling to Taos, New Mexico several times. She stayed with Luhan at her Pueblo and absorbed inspiration that would eventually lead to the creation of two works, El Penitente, which was based on Southwestern Christian-based traditions, and Primitive Mysteries, based on indigenous religious rituals.

Importing Culture; Raising Awareness

In the years since the portraits of St. Denis and Shawn were created, the Pillow has hosted performers from around the world and shared many diverse dance forms not often seen outside the borders of their country of origin. There is no doubt that dance can broaden its audience’s frame of reference and, hopefully, increase its appreciation of cultures different from one’s own. What began with Denishawn traveling to other countries and bringing home dance styles that they learned abroad, eventually evolved into Shawn booking non-white performers of various non-euro-centric styles at Jacob’s Pillow. One could argue that he built bridges to white audiences for non-white performers, though it is also worth noting that the lion’s share of “ethnic dance” teaching at the Pillow was carried out by La Meri, the white American soloist known for her Spanish and East Indian dancing.

In an interview with Jac Venza for PBS in 1969 (featured in the PillowVoices podcast, episode 9, “Ted Shawn, Jacob’s Pillow Founder, In His Own Words”), Ted Shawn discusses his “ethnic” dances in this way: “Now, some people thought that I just copied things, but no, I studied the original, absorbed the original, and then I did a creative choreography, based upon this original material. True to it, but not in any way an imitation of it. And this is always what we did with the ethnic material.”

This understanding of ownership—from the Euro-dominant/colonizer perspective, negates a vital piece of the puzzle, which is lived experience. A dance from a particular culture is more than steps. It is more than learning to move in a certain style, with music related to that style and culture. The form is an expression and an extension of living in the world, with the physical attributes, communities, and traditions from which the dance is derived. This is a point of learning for white artists, students, and academics, particularly when looking at and working to reconcile the impact of ‘dance pioneers’ in the United States, who founded many of the systems and spaces that support dance. As we work to develop lenses of equity and try to include all genres in the canon, we must include lineage in the conversation.

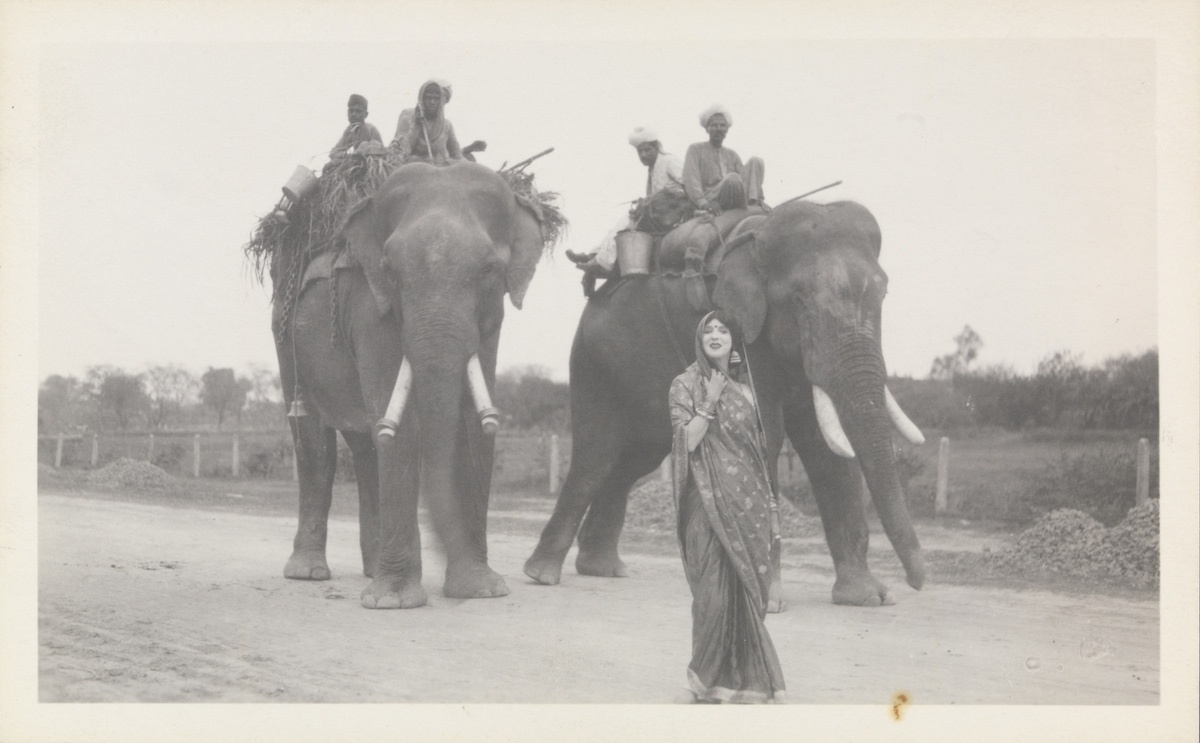

There are at least two streams of lineage in this equation, however. One is the origin culture of the dance, while another is the origin culture of the dancer/choreographer. When Denishawn and others like La Meri were traveling to India, for example, the sub-continent was under British rule (held until 1947). The dominance of colonial culture and the daily acceptance of white people taking Indian art and artifacts from origin cultures went unquestioned. One could say that these modern dance pioneers were imposing their culture—a culture of appropriation—on the places to which they traveled. And their travel was facilitated by the occupation of their own culture of origin.

And yet, as we will explore below in the section Dance as Cultural Exchange, it is human nature to want to share dances and movement across cultural divides. This further complicates such investigations. However, many dancers and choreographers did not simply study with masters of various cultural dance forms. Many Western artists presented works in costumes of the cultures from which they derived inspiration, thereby directly referencing and appropriating those cultures, and some of these works continue to be staged. We must also talk about how lineage is conveyed, taught, and held, as this is yet another layer of appropriation. For if Shawn was inspired by studying with, for example, a Japanese Kabuki master, his choreography of that experience reflects a brush with that lineage. He is not part of or a holder of that lineage. And then if he sets his choreography on white dancers and that work enters the repertory of a white company, effectively any first-hand understanding of the form itself disappears. The same holds true for La Meri teaching “ethnic dances,” like Javanese dances, to students at the Pillow. While La Meri studied with dance masters in Java, her understanding of the culture was second-hand.

Referring back to the example of Martha Graham, a next-generation Denishawn dancer, both El Penitente and Primitive Mysteries were inspired by Graham’s experience of others’ rituals but did not in any way overtly refer to them. The difference being, that while Denishawn approximated the movement and costume of the cultures they were inspired by, Graham translated her experience through her body, her technique, and signature costuming and music composition by Louis Horst. The pieces convey a ritual, performed by the specific group on stage, not an indigenous ritual re-imagined on white bodies for a white audience.

In that same interview with Jac Venza, Shawn went on to convey a narrative that others have articulated as well—that dance somehow exists outside the confines of race, creed, and class. This perspective weaves a utopic view of dancers coming together, in spaces like the Pillow, and then transcending the structures of society. The idea is that the act of dancing levels the inequities of society itself. However, this is a notion that only people who enter every space with the freedom of white privilege can dream to be true.

In this exploration, I do not aim to dismiss the important work of cultural sharing and of importing art and artists from around the globe to perform for mostly American audiences at the Pillow. However, even as I suggest below that you view some of the works housed in the “Cultural” dance vertical of the Dance Interactive as evidence of such undertakings, I acknowledge the ghettoization of such forms. For here, too, we run into the problematics of language—and once again we come to this question: Can art and dance artifacts amend history—not edit, not fix, but amend?

Perhaps the larger question is: What would be the best solution for how to present works from cultures other than our own? To organize each form into much smaller, but more specific genres might remove it from a larger conversation and minimize the potency of ‘belonging’—but lumping all non-Eurocentric forms into one group is to contextualize them only in terms of what they are not. This is currently a hot topic that decolonizing-arts-initiatives are undertaking. I look forward to a time when this essay is amended to reflect the outcomes of that work.

Nevertheless, non-Eurocentric dance and music have been a part of Jacob’s Pillow’s history from the beginning. Below are two examples of performers and forms Shawn brought to the Berkshires.

Asadata Dafora, born in Sierra Leone in 1890, moved to the U.S. in 1929 and started the African Opera and Dramatic Company and a dance troupe known as Horton’s Dancers. He debuted in the first Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival season in the newly built Ted Shawn Theatre in 1942. For more, see the full Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive essay “Asadata Dafora” by John Perpener.

Indrani (1930-1999) was born into a dance family as the daughter of Ragini Devi, a pioneer in India’s dance revival who wrote the first book in English on Indian dance and was the first to perform Kathakali abroad. She made her U.S. debut at the Pillow in 1960. This clip is of her last performance at Jacob’s Pillow in 1979.

Dance and Cultural Exchange

In her book, Dancers as Diplomats, Clare Croft highlights the role dance can play in true cultural exchange. “Dance has a particular route to considering what the United States as global partner, rather than just a dominant power, might look like. Dance’s possibility, not only as a concert form, but as a way to create space for international collaboration, is a key rationale behind dance’s inclusion in contemporary cultural diplomacy programs. … month-long tours center primarily on community engagement, rather than concert performances. The logic behind this collaborative turn in dance-in-diplomacy seems to be that physical sharing, considered as less reliant on language, enacts intercultural exchange with U.S. representatives as partners as well as leaders.”

During the summer festival at Jacob’s Pillow, each week two new companies arrive and unload props, sets, costumes, and cast members—one company into each theater—to rehearse and perform. The companies are in many ways separated from one another except for mealtime, where everyone—dancers, students, staff, interns, and guests—eat together. As a Scholar-in-Residence I’ve witnessed that a key moment in the weekly activity and exchange between companies happens on the dance floor. Every Saturday night, the resident companies, interns, staff, students, scholars, and some of the board members and supporters of the Pillow, gather for a dance party. The magic of this party is not documented, and it is rarely discussed, but on one night in 2016, I experienced the coming together of two groups of dancers, one from Argentina, and the other from South Korea.

None of these dancers were able to communicate with each other in words. Bereishit, the South Korean company consisted of contemporary dancers and traditional Korean opera performers. Che Malambo, from Argentina, was a group of men who perform a traditional gaucho dance and music form, described below. They did not even have a common movement vocabulary through which to communicate. However, when they hit the dance floor, along with students who had been in residence with Urban Bush Women, none of this mattered.

Circles and lines formed organically, and dancers took to battling, borrowing movement from each other, dancing together, smiling, and cheering each other on. As Croft outlines in her writing, true exchange comes through sharing on equal ground, not simply observing. And so, there is a case to be made for the non-performative aspects of the Pillow—the dance parties and conversations between audience members, scholars, and artists—and for the Archives themselves, as spaces for deeper cultural exchange. As difficult as it may be to weed through biases and discomfort, spaces on campus like the Archives offer a certain equity and autonomy for its artifacts and its visitors.

During that same week in 2016, I was the Scholar-in-Residence assigned to speak on behalf of Che Malambo and I learned quite a bit about cultural exchange through researching the history of this art form. As various populations migrated or were imported to Argentina from West Africa, Ireland, Russia, and Spain, people communicated with the tools they had, often through dance and music. A new form of dance came about and lives on in the bodies and lived experiences of those who perform it. In this way, dance itself can become a living, breathing artifact and archive that one may read and excavate to uncover its lineages.

Conclusion

If we return to the original question: Can art amend history and, by extension, could Jacob’s Pillow serve a similar purpose, I believe the answer is maybe. What the Pillow does already is offer a space to consider this question. By ‘placing’ the portraits of Shawn and St. Denis next to the artists onstage (Che Malambo, for example), I would argue that the Pillow is inviting us to do exactly this work—acknowledge the past, place it adjacent to the present, and dream of what may come. This is an undertaking, however, that one must train for, and I believe it is the next phase of work to be done. As James Baldwin so eloquently wrote in his essay titled Unnameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes, “History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.”

When considering the origin points of modern dance, of Jacob’s Pillow, and of dance as we experience it today, we must expand the conversation and do the truly hard work of mapping ALL of the factors at play. Lineage, multivalent [hi]stories, mapping colonies, migration, forced migration and slave trade routes, and objective exploration of influences are important places to start. However, the true starting point is owning the impact of white-dominant culture at play in society, dance education, and in dance itself. We must not only learn, but prioritize the incorporation, elevation, and teaching of the entire, complex story of this living, embodied form. Knowing that cultural exchange and sharing is vital, the true questions to ask and answer in exploring history are: 1) who controls the narrative, 2) who benefits from the work created, and 3) who pays a price in the process.

Endnotes / Bibliography

Titus Kaphar TED Talk “Can art amend history?”

PillowVoices Episode 9, “Ted Shawn, Jacob’s Pillow Founder, In His Own Words” with Norton Owen

“Cultural” genre on the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive

“Asadata Dafora” Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive essay by John Perpener

PillowVoices Episode 11, “The Life and Work of La Meri” with Nancy Wozny