Introduction

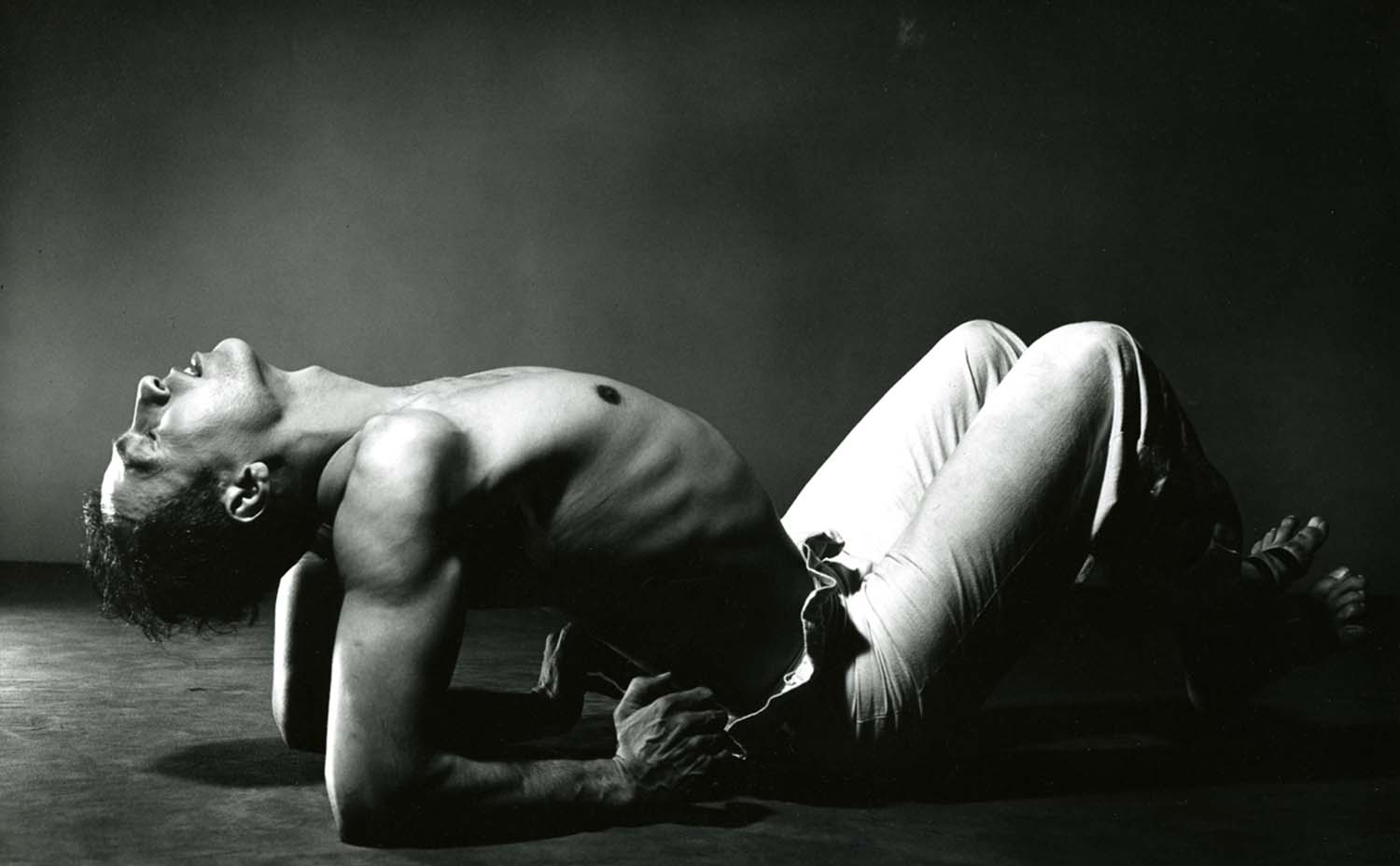

For this essay, I discuss works by José Limón that offer possibilities to consider his experiences of race, ethnicity, and bi-nationality throughout his career while focusing primarily on elements from Danzas Mexicanas and La Malinche. Though there is no footage of Limón performing these particular works within the Jacob’s Pillow Archives, his powerful performance style may be sampled in this excerpt from a work that Doris Humphrey created especially for him, also with a Mexican theme.

Influences: Danzas Mexicanas

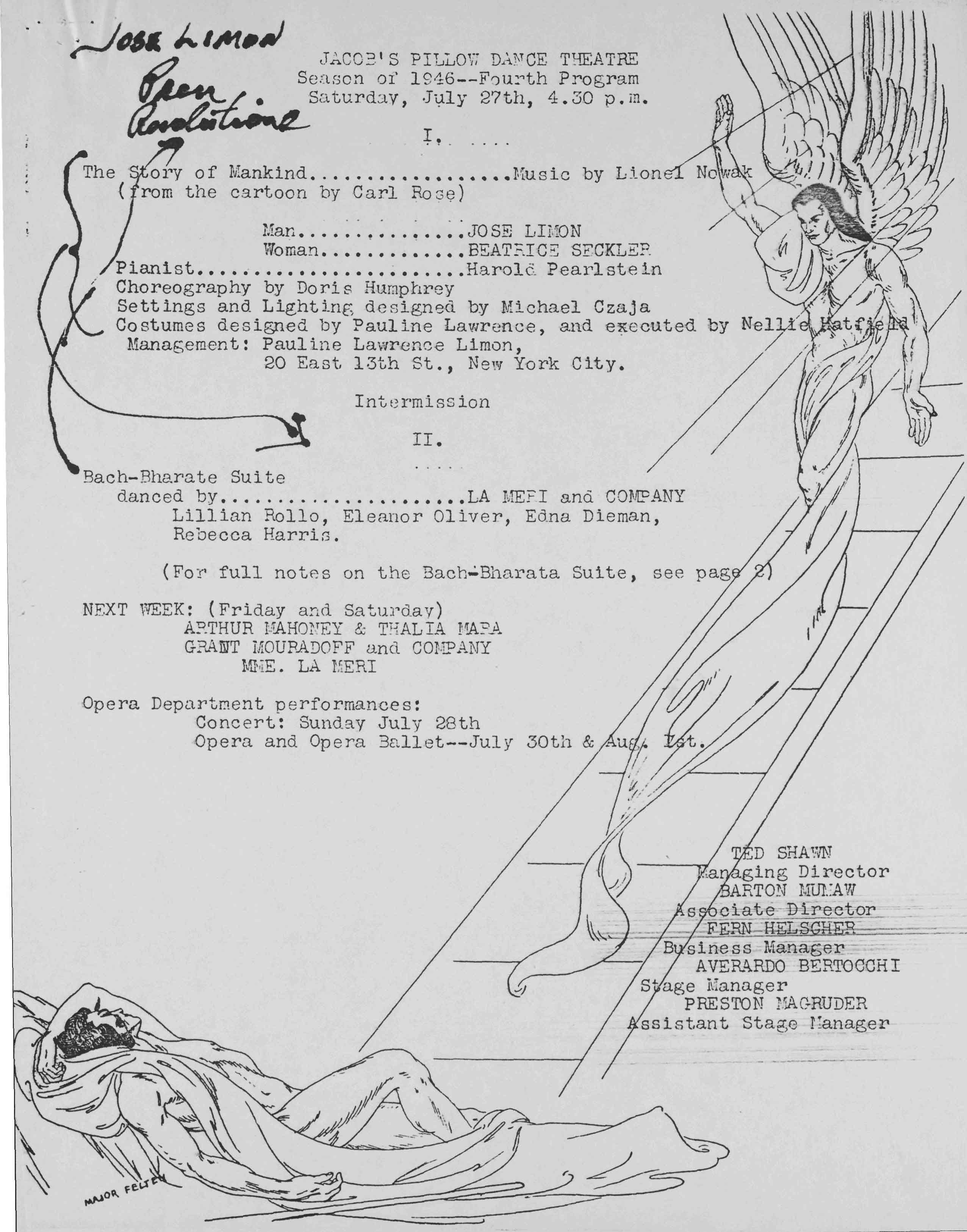

Before the founding of the José Limón Dance Company in 1946 with Doris Humphrey as its Artistic Director, Limón’s first major choreographic work, Danzas Mexicanas, premiered at Lisser Hall at Mills College in Oakland, California in August of 1939. The piece, originally called Murals of Mexico, was a series of five solos in which Limón drew inspiration from Mexico’s history, the land, and its peoples. Each included figures informed by Spanish colonization and resistance: Indio, Conquistador, Peón, Caballero, and Revolucionario. By 1939, Limón had been living in the U.S. for more than twenty years and in New York for approximately ten. He would write later in his memoir, “the cruel, heroic, and at the same time beautiful story of my native land has long held a singular fascination for me. It is never entirely absent from my thinking.”Limón, José, and Lynn Garafola. José Limón: An Unfinished Memoir. Wesleyan University Press, 2001, 90-91.The five solos in Danzas Mexicanas and corresponding characters included broad thematic portrayals of destruction, redemption, triumph and despair, weaving interpretations for audiences of the time. Notably, he chose to present two of these five solos (Peón and Revolucionario) during his first engagement at Jacob’s Pillow in 1946.

Limón’s focus in Danzas Mexicanas was influenced by factors both close and immediate and possibly on a national scale. At the time of its creation, there was a surge in interest in Mexican art and artists in the early 1930s, and an increasingly vibrant painting scene in New York City, as Mexican muralists such as José Clemente Orozco, Miguel Covarrubias, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros were redefining mural painting by deeply influencing the form and helping to develop a generation of renowned painters. Drawing lines between history and the moment, Limón based the Conquistador character on Orozco’s vision of Hernán Córtez.Limón, José, and Lynn Garafola. José Limón: An Unfinished Memoir. Wesleyan University Press, 2001, 90-91.Once a painter himself, he located visual imagery and stories that referenced his homeland and vibrant Mexican narratives as he created works such as Danzas Mexicanas early in his career.

Another plausible influence on Limón’s artistic choices was the anti-Mexican sentiment in the U.S. during the Great Depression era. Limón’s family had immigrated to the U.S. in 1915 when he was seven years old. Later, during the 1930s approximately one million people of Mexican descent, and many who were U.S. citizens by birth, were coerced into leaving or were deported to Mexico on the racist belief that Mexican immigrants were using resources and working jobs that should be given to white Americans affected by the economic depression.Gross, Terri, and Francisco Balderrama. “America’s Forgotten History Of Mexican-American ‘Repatriation’.” Fresh Air, National Public Radio, 10 Sept. 2015. https://www.npr.org/2015/09/10/439114563/americas-forgotten-history-of-mexican-american-repatriationThis practice was euphemistically referred to as repatriation and took place throughout the country. Today this violent rhetoric echoes similar anti-immigrant and anti-brown sentiments espoused nearly a century later, and decades since Limón’s death.

It might seem contradictory to say on one hand that Mexican art and artists were celebrated, while people of Mexican descent living in the U.S. were coerced into leaving, but this is part of what I am interested in acknowledging by considering Limón’s artistic choices at precisely this moment. It illustrates how ordinary people of Mexican descent were placed within a system that racialized their brown bodies as foreign and other, while at the same time, celebrated a romanticized culture and a select few, resulting in a conditional belonging for some. The famed Mexican muralists of the time identified to varying degrees with their “former countrymen” as Rivera called the Mexican American workers who were affected by the repatriation.Guerrero, Marcela. “Friends, Foes, or Strangers: Mexican Americans and the Mexican Muralists in the 1930s” Vida Americana, Mexican Muralists Remake American Art 1925-1945, edited by Barbara Haskell, Whitney Museum of American Art, Yale University Press, 2020, pp. 208-213.Furthermore, this system perpetuated an oversimplified idea of Mexico and its peoples, invisibilizing Indigenous peoples and people of African descent in the country.

As a brown immigrant whose early work coincided with the tumult of the 1930s, Limón found in dance a way to survive and a way to tend to his sometimes disparate branches of belonging and acceptance. Limón found in dance a way to survive and a way to tend to his sometimes disparate branches of belonging and acceptance. The personal journey of these histories, reimagined through his dances, brings to mind more questions. What were his experience(s) as an immigrant at this time, and how might they have influenced his choices in making these works? How did the predominately white audiences he performed for in the U.S. influence the artistic choices he made when he created dances about his homeland? On the topic of Limón’s shifting place in regard to race within the genre, dance scholar James Moreno writes, “even though the transient quality of Limón’s identity could be seen as a move that expanded racialized boundaries and diversified mid-century U.S. modern dance, his work did not break down or synthesize the prevailing black/white racial boundary.”Moreno, James. The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Politics, by Rebekah J. Kowal et al., Oxford University Press, 2017.Limón was afforded a racial fluidity that allowed him to portray white and non-white figures, which in turn allowed him to traverse his own identity as a mixed descent brown man, and also the identities of other non-white subjects.

The Dance: La Malinche

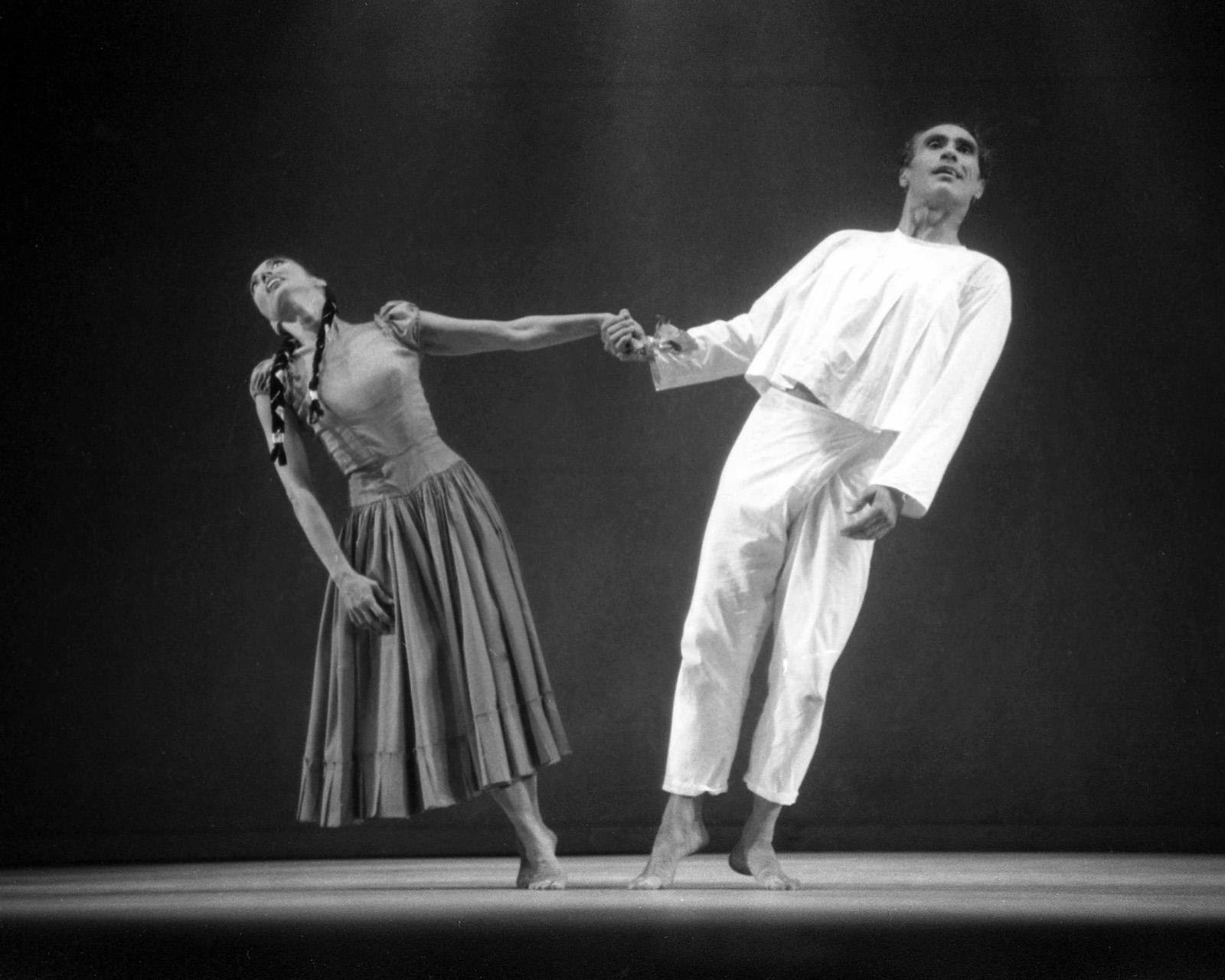

This navigation of identities found its way into several of Limón’s works, and perhaps most outrightly in La Malinche (1949). A powerful figure in Mexican history and mythology, the history of Doña Marina Malintzin is multi-layered. By historical accounts, she was an enslaved multilingual Nahua woman who was a translator and interpreter for, and also mistress of Hernán Cortés following his arrival in Mexico in 1519. Throughout history, Doña Marina Malintzin, or La Malinche as she is widely known, has been both maligned as a traitor and also regarded as a brilliant liaison and advisor, as scholars today acknowledge her story and its context more fully. Limón attempted to summon her and contend with the conquest of Mexico through the story of Malintzin played by Pauline Koner, accompanied by Lucas Hoving as Hernán Cortés, and Limón himself as El Indio. Koner was of Russian Jewish heritage and Hoving was Dutch. As colleagues who often worked together, the group developed their solos to suit their familiar styles.

Onstage, the intersecting histories of these symbolic characters are made clear through patterns and choreographic transitions. They enter together, “first circling the performance space, both limiting and inscribing the circumference of their metaphorical world.”Berg, Shelley C. “Limón’s La Malinche: Negotiating the In-Between.” Dance Research Journal, vol. 37, no. 1, 2005, pp. 75–93.Later, a duet between La Malinche and El Conquistador concludes with her plunging his sword toward the earth between the two of them, forcefully and symbolically marking a middle space, and a space between two beings and two cultures. At the conclusion of the work, La Malinche and El Indio dance together in a battle against El Conquistador as he slowly dies.

In reflecting on the heavy symbolism here, this moment is less a resolution of a conflict than an acknowledgement of continued embodied multiplicities. Limón was acknowledging himself as the descendant of these histories—an embodied middle ground who was perpetually in translation across race, language, nationality, and as a male dancer in the 1940s, across gender as well. As dance historian Shelly C. Berg notes, “Limón, already feeling a conflict between his Mexican and Spanish heritage, saw his choreography as a way to embed his ethnicity within the evolving aesthetic of American modern dance.”Seed, Patricia. José Limón and La Malinche: The Dancer and the Dance. University of Texas Press, 2008.By focusing on La Malinche and its motifs, I am speculating about Limón’s ideas of belonging and how they influenced his artistic choices. The story of Malintzin represents this arranging and scaffolding of identities for Limón, both with him and apart from him. It was a generative space and these themes would continue to appear in later works. Still, I sense that there is much more to consider where the dancer begins to meet his own origin stories, mythic and otherwise.

Assembling a Picture of a Life

Limón’s written account of his life, the aptly titled An Unfinished Memoir, ends before La Malinche and a tour in Mexico (where he premiered five new works) can be included within it. He began writing his memoir when already ill in the 1960s, and wrote chronologically, starting with the story of his birth, and ending just shy of the better part of his celebrated career. I’ve often wondered what his authorial intent was in arranging his memoir this way. Was it omission by design—a way to perhaps avoid revealing too much? Or instead, was it a conscious attempt to not be separated from his origins, and to tend to his own beginning first? Reading the memoir with a hunger to truly know the artist, or his life in its entirety, is like listening to two clocks unwind at different speeds—the distance between each increasing as time moves on, with a nagging feeling of time running out.

Limón was a “man of color who was grappling with the European hierarchy of beauty and importance."

Assembling a clear picture of Limón’s relationship to brownness and Indigenous heritage is difficult because of how little has been written about these topics specifically. His mother, Francisca Traslaviña, descended from peoples Indigenous to Mexico and the borderlands and his father was of Spanish and French descent. His mother’s family “did their best to disregard their Native American ancestry.”Seed, Patricia. José Limón and La Malinche: The Dancer and the Dance. University of Texas Press, 2008.This disregard was noted by Limón himself and attitudes in Mexico and the U.S. would have contributed to this distancing in which Spanish ancestry was elevated and Indigenous ancestry frowned upon. Much of what is written about this and its impact on his work is mentioned in passing or second-hand. As Bill T. Jones notes in Ann Vachon and Jeffrey Levy-Hinte’s 2001 documentary José Limón: A Life Beyond Words, Limón was a “man of color who was grappling with the European hierarchy of beauty and importance.”Roth, Malachi, and Ann Vachon. Limón: A Life Beyond Words. Dance Conduit, Antidote Films 2001.Jones’s observation briefly acknowledges Limón’s creative relationship to that hierarchy and offers a lens to consider his artistic choices.

Can we collectively piece together a further history of Limón as a dance artist, and what might that offer up about not only Limón, but about dance and belonging, dance and racialized bodies, and dance and trauma and complex experiences of being both othered by and included within whiteness? I am asking myself this just as much as I am posing the question to the reader. I am hopeful that we are slowly acknowledging these chasms in recognition and centering intentional acknowledgement and conversation for recognition and accountability on a larger scale.

Conclusion

Though Limón has been described as having felt conflicted about his early years, his dances incorporating his Mexican heritage invite a closer reading of his work overall.These aesthetic navigations, and resulting blurring of identities, created their own artistic sensibilities, in part, giving Limón’s oeuvre the range of expression and appeal that it does. Though Limón has been described as having felt conflicted about his early years, his dances incorporating his Mexican heritage invite a closer reading of his work overall. And though we are increasingly distant from the better part of Limón’s career as a dancer, choreographer, and collaborator, these issues continue to live on in the company and invite further dialogue about the past, present and future representations of dance makers’ lives and work.

Endnotes

The relationship of the Mexican muralists, Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros to the repatriation of Mexican Americans is considered more in Friends, Foes, or Strangers: Mexican Americans and the Mexican Muralists in the 1930s, Marcela Guerrero’s catalog essay for Vida Americana, Mexican Muralists Remake American Art 1925-1945, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2020.

Special thanks to Ahimsa Timothy Bodhran, Alexander Duque Cifuentes, Anthony Rosemary, and Yvonne Montoya.