The Beginning

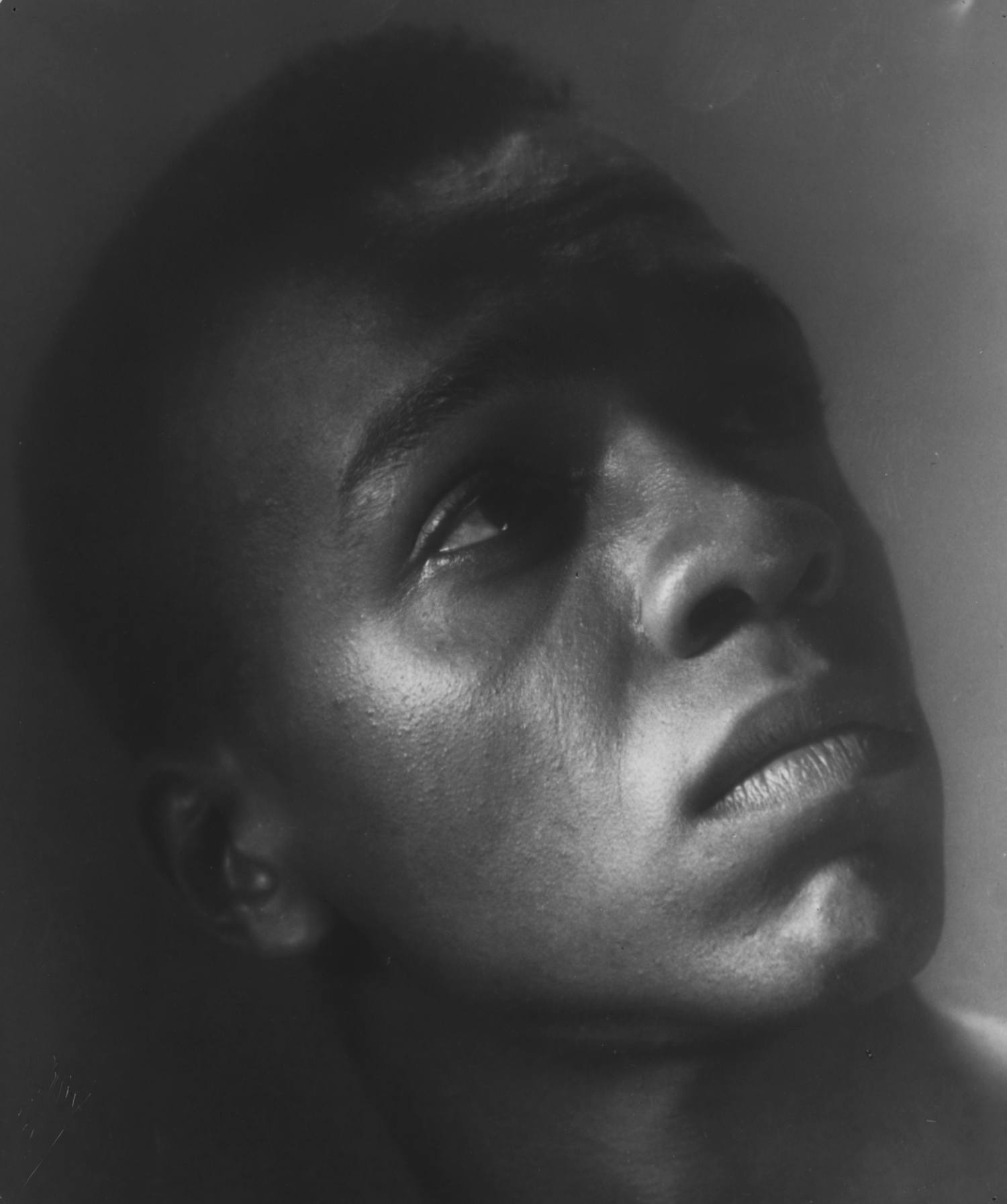

As Donald McKayle recounted in an interview at Jacob’s Pillow, he first met Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis in 1952 when he was invited by Doris Hering to share a joint concert with them at the Museum of Natural History in New York City.Norton Owen, Interview with Donald McKayle, Joe Nash, and Chuck Davis, August 20, 1998, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.McKayle was mesmerized by Shawn and St. Denis’s offering of duets and solos that included their standard repertory works such as Josephine and Hippolyte, Spear Dance, and Black and Gold Sari. Ibid. McKayle’s part of the program consisted of his newly-choreographed work Games, which he had premiered at the Hunter Playhouse a year earlier. Impressed with the young artist’s work, Shawn invited him to appear at Jacob’s Pillow the following summer, and also asked him if he could present a new work. McKayle was working on Nocturne at the time, so Shawn’s request fit handily into his plans.Ibid.

McKayle had been influenced by a number of experiences by the time he embarked on a choreographic career. When he was growing up in New York City, his curiosity often led him to explore the city’s theater district, where he stood outside the theaters and looked admiringly at posters and photograph of shows that were currently running on Broadway. One set of images—stunning photos of Katherine Dunham and her company—had a particularly magnetic impact on him, so he made it a point to see the show. He was amazed by the theatrical magic of her revue in sections like “Haitian Roadside.” He later remembered how impressed he was with the spell that Dunham cast over her audiences. At one point in the show, she entered from the wings, beautifully costumed and lit, singing softly and sweetly, and leading a live donkey.Philip Szporer, Interview with Donald McKayle, 2000 Season Artists’ Series (June 21 – Sept., 2000), Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

His earliest exposure to formal dance training occurred when he studied at the New Dance Group, where his teachers included Sophie Maslow, Mary Anthony, Pearl Primus, and Jean Leon Destine. He had, in fact, decided to audition there after he saw a Pearl Primus performance that—like the Dunham concert—left an indelible impression on him. He threw himself into his studies, and his career developed quickly, leading him to dance with the companies of Mary Anthony, Jean Erdman, Merce Cunningham, and Anna Sokolow; and during the 1955-56 season, he performed with the Martha Graham Dance Company on their U.S. State Department tour of Asia. During the early 1950s, McKayle also established another aspect of his multi-faceted career—musical theater performance and choreography—with his appearance in Helen Tamiris’s Broadway show Bless You All (1950), and a few years later he appeared in the ground-breaking, all-black musical House of Flowers (1954).

1950

The early 1950s was a period when a number of white modern dance choreographers were not only pioneers in developing new directions in contemporary dance, but they were also opening doors for African-American dance artists by diversifying their companies. This progressive initiative intersected with the attention McKayle was receiving as a promising new artist:

I was suddenly the bright new light on the dance horizon, the subject of newspaper articles and magazine feature stories, as the director of one dance company, and a member of four others. . . . I was the male dancer in Jean Erdman’s company, and by dint of the singularity of that position, a leading dancer. Merce Cunningham asked me to join his company for a special commission, the gala event opening of the Art Center at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Anna Sokolow had returned from her sojourn in Mexico and extended to me an invitation to become a member of her newly formed company . . . . Could I do all of this? The answer was yes, gladly, happily, exhaustedly, yes.Donald McKayle, Transcending Boundaries: My Dancing Life (London and New York, NY: Routledge Books, 2002) pp. 54-55.

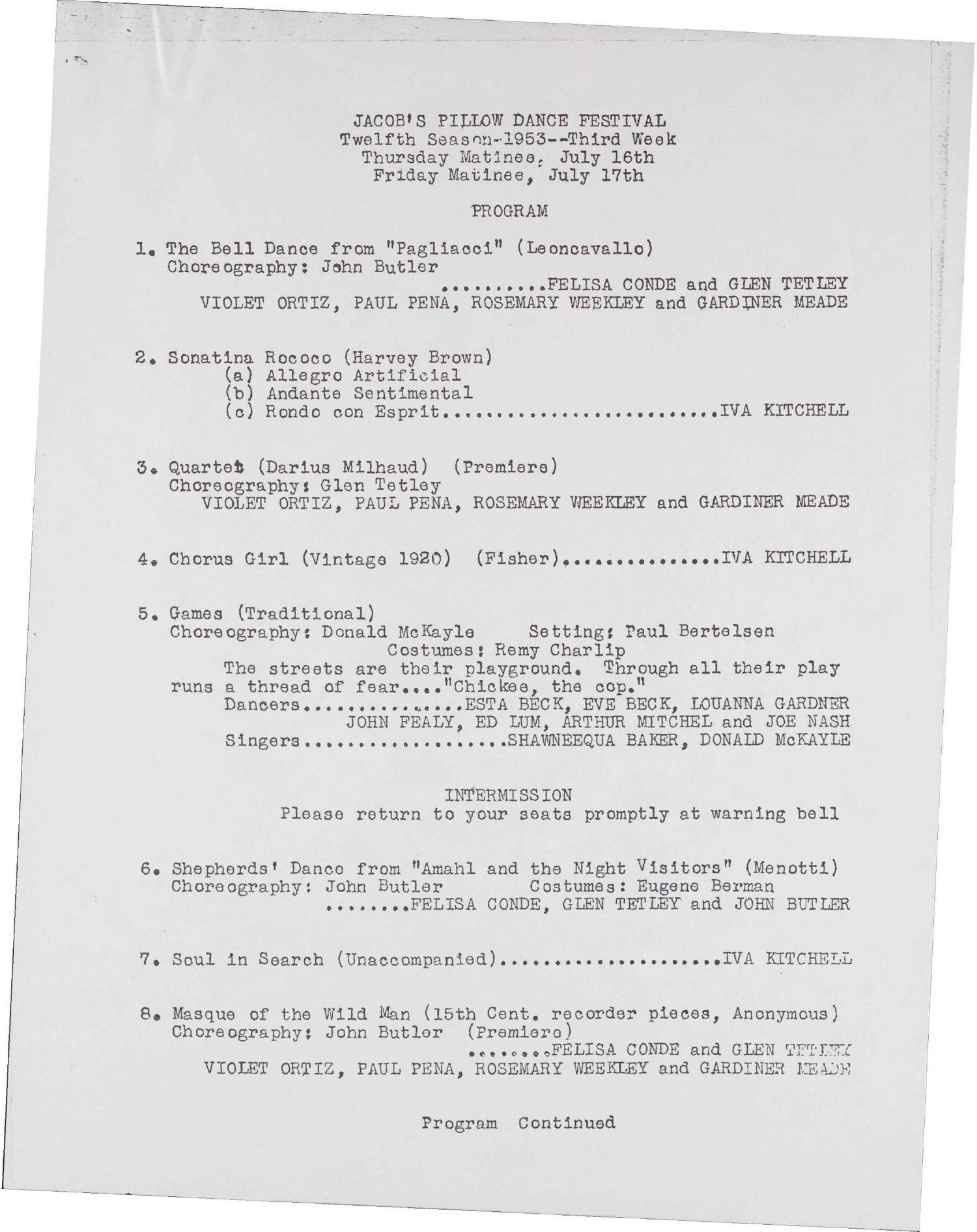

To his full plate of activities, McKayle added his company’s appearance at Jacob’s Pillow on July 17 and 18, 1953. Donald McKayle and Company included Arthur Mitchell, who had just graduated from New York’s High School of Performing Arts and had been accepted as a scholarship student at Lincoln Kirstein and George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet. During this period—prior to being accepted into the New York City Ballet in 1955—Mitchell continued to perform with modern dance companies. Another of McKayle’s dancers, Joe Nash, had a career that included touring with Pearl Primus in 1946, appearing in Bless You All with Donald McKayle in 1950, and in his later years building an extensive archive of material on the history of African-American dance and lecturing widely on that topic. McKayle’s company was rounded out with Shawneequa Baker, Esta Beck, Eve Beck, Louanna Gardner, John Fealy, and Ed Lum.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Twelfth Season—1953.

Games, the work that Shawn had been so impressed with in New York, was McKayle’s first critically-acclaimed choreography of his early career.

He often explained how the underlying idea for the work was that playful games can serve as a training-ground for children’s socialization as they relate to the world around them. Moreover, he was inspired by a specific childhood incident in the Bronx when he and his playmates were playing in the streets, and a local policeman approached to harass them. They all ran into the alley to hide, except for one kid who went back to retrieve his handkerchief. The others looked back to see the policeman beating him with his night-stick. In an essay published years later, McKayle captured the event in his own words:

“It was a childhood memory that triggered my first dance. . . . It was dusk, and the block was dimly lit by a street lamp around which we hovered choosing a game. The street, playground of tenement children, was soon ringing with calls and cries, the happy shouts of the young. The street lamp threw a shadow large and looming—the constant specter of fear—“Chickee the Cop!” The cry was broken; the game became a sordid dance of terror.”Donald McKayle in Seven Statements of Belief, Selma Jeanne Cohen, ed. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1965) p. 57.

Early Career

Games was an early work that helped establish a genre of concert dance that explored the experiences of African-Americans living in oppressive urban environments. Talley Beatty would contribute to that genre with his Road of the Phoebe Snow (1959), as would Eleo Pomare with his Blues for the Jungle (1966), both of which were performed at the Pillow. It is also a genre that has been explored by today’s younger choreographers such as Rennie Harris with his Endangered Species and Kyle Abraham with Pavement. Both of those works were also later performed at the festival, in 2005 and 2013 respectively. What stands out about McKayle’s early work of this type is that he explored the ills of contemporary urban life as seen through the eyes of children emerging from a chrysalis of innocence into the more daunting realities of racial prejudice in America.

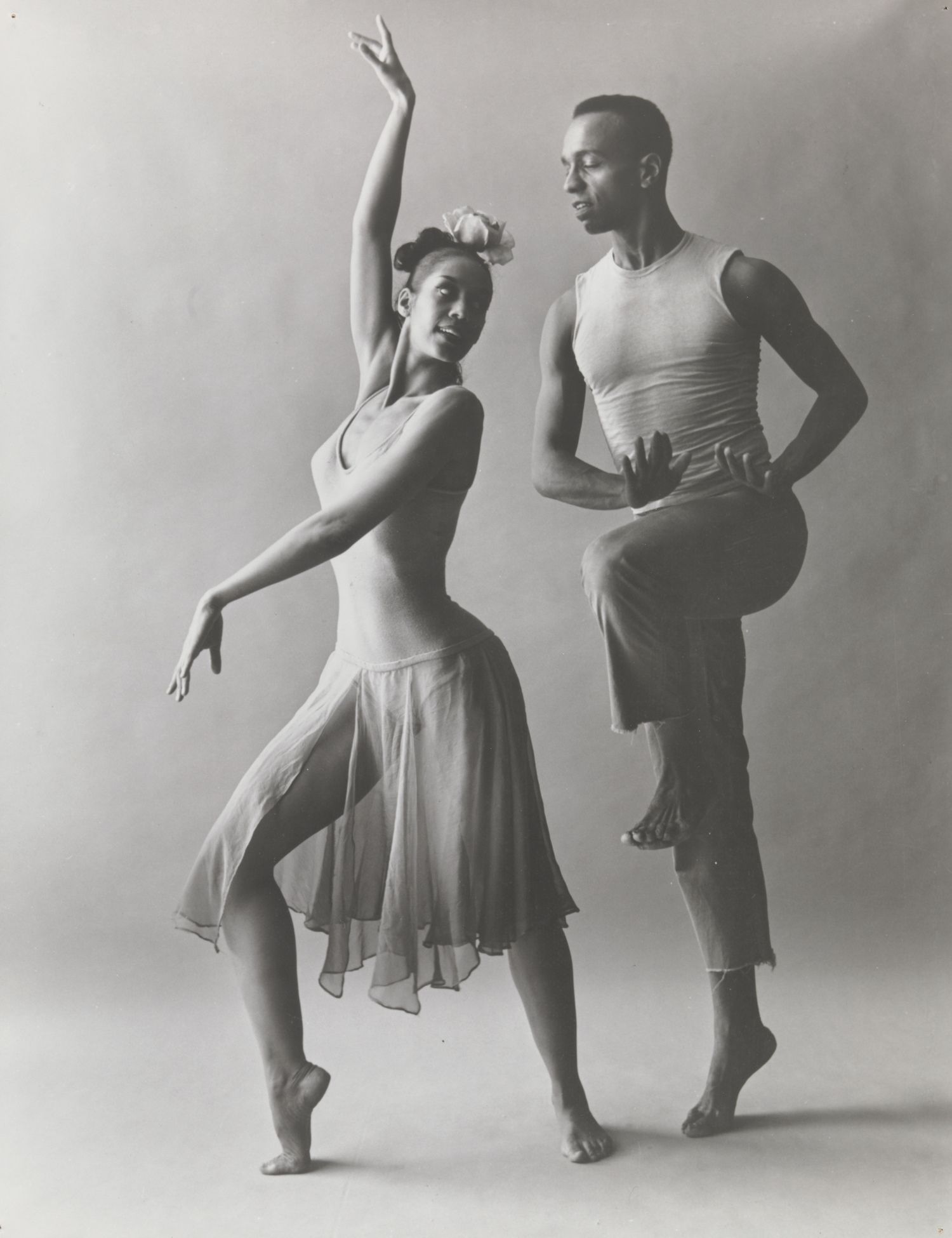

In his 1965 essay, McKayle also described the other dance his company performed on the 1953 Pillow program:

“Nocturne is a lyric dance that grew out of a first love with the music of Moondog. Its basic material is pure movement, yet it is not movement in a void of mood or idea. The dance celebrates the qualities of man and woman. Man is depicted in his role of discoverer, protector; woman as inspirer. The male patterns are large, thrusting, laced with impulse, volatility, and expectation. The female movements are flowing, curved, inviting. The resulting duets are a blending of both qualities.” Ibid.

Nocturne was also one of McKayle’s dances that was later revived at the Pillow by the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Company in 1996.

During the years between his first and second visit to Jacob’s Pillow, McKayle continued choreographing major new works including some that explored epic stories rooted in African-American history. From an early age, he had read widely in that area, and during one of his forays at a children’s library, a helpful librarian suggested that he go up to Harlem to the Schomburg Collection as a way of pursuing his interests.Philip Szporer, Interview with Donald McKayle. His continuing interest in black history eventually influenced the creation of works like Her Name Was Harriet. He based the dance on the life of Harriet Tubman, a woman whose legendary efforts guided slaves to freedom on a journey north that became known as the Underground Railroad. Though Her Name Was Harriet was never performed at Jacob’s Pillow, it is interesting to note that the old farmstead where the festival had been established was said to have been a stop on the Underground Railroad for slaves moving north to Canada. So in a sense, freedom-seekers like Harriet Tubman are indeed connected to the Pillow.

Political Movement

Over the years, McKayle’s own activist nature often moved him to become involved in several protests against social and political injustice. At the age of seventeen, a few years after enrolling at the New Dance Group, he joined a group of activists/artists that included Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Langston Hughes. Among their organization’s politically progressive activities, The Committee for the Negro in the Arts, held a rally in support of Paul Robeson, the outspoken actor and singer. He had been blacklisted, and his passport had been revoked by the U.S. government; consequently, he could not travel or find work to support himself. McKayle performed a solo at the benefit, accompanied by Robeson’s booming voice singing “Bye and Bye.” Transcending Boundaries, p. 36.

In another instance, McKayle’s protest occurred when he insisted on dancing at an audition where the stage manager had informed him that no Negroes would be used in the show. He brushed the comment aside and auditioned anyway, turning in an outstanding performance. The other dancers applauded him enthusiastically as he walked out. As he stated in his biography, “It wouldn’t be the last time that I stood up for my rights.”Ibid., p. 164.

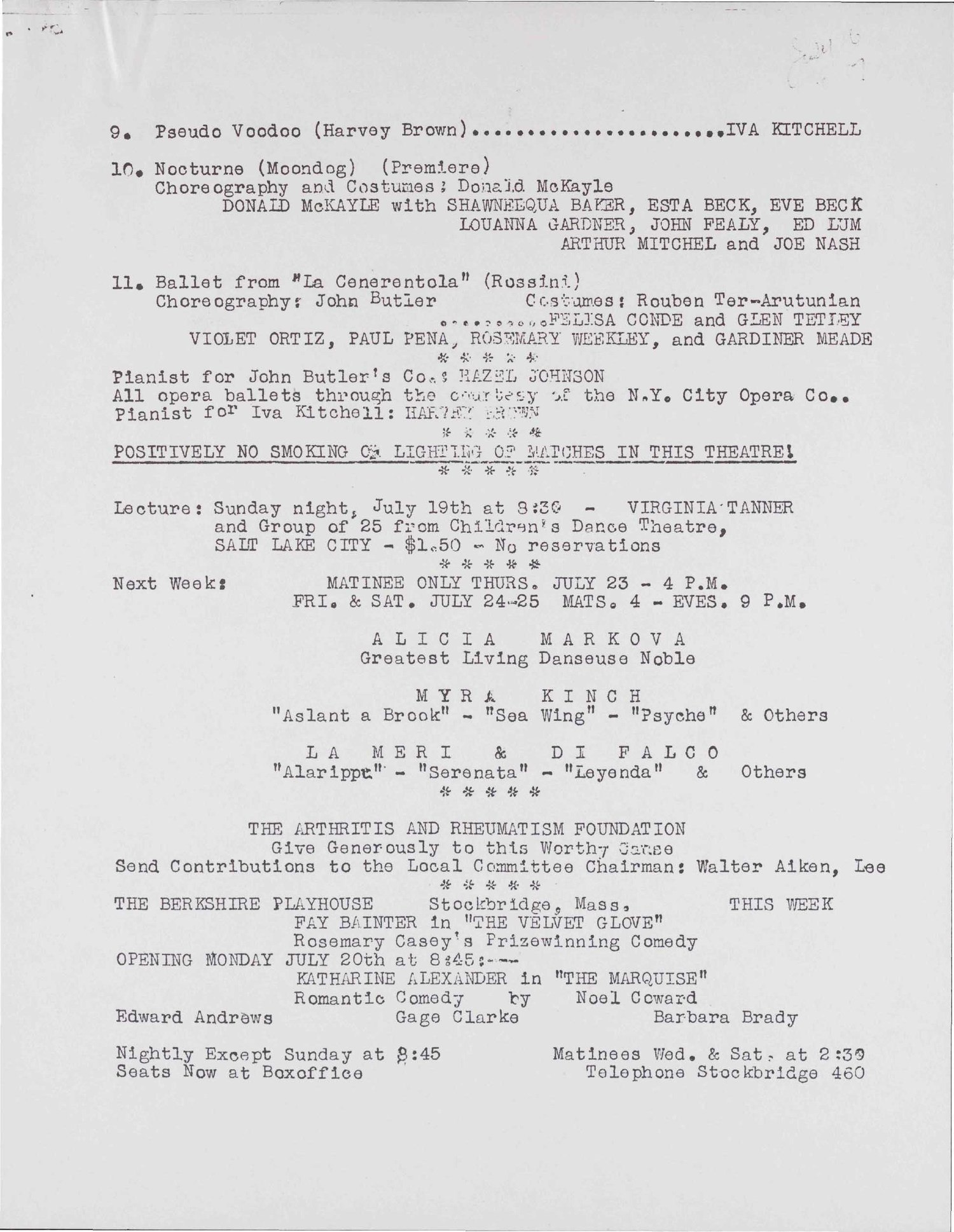

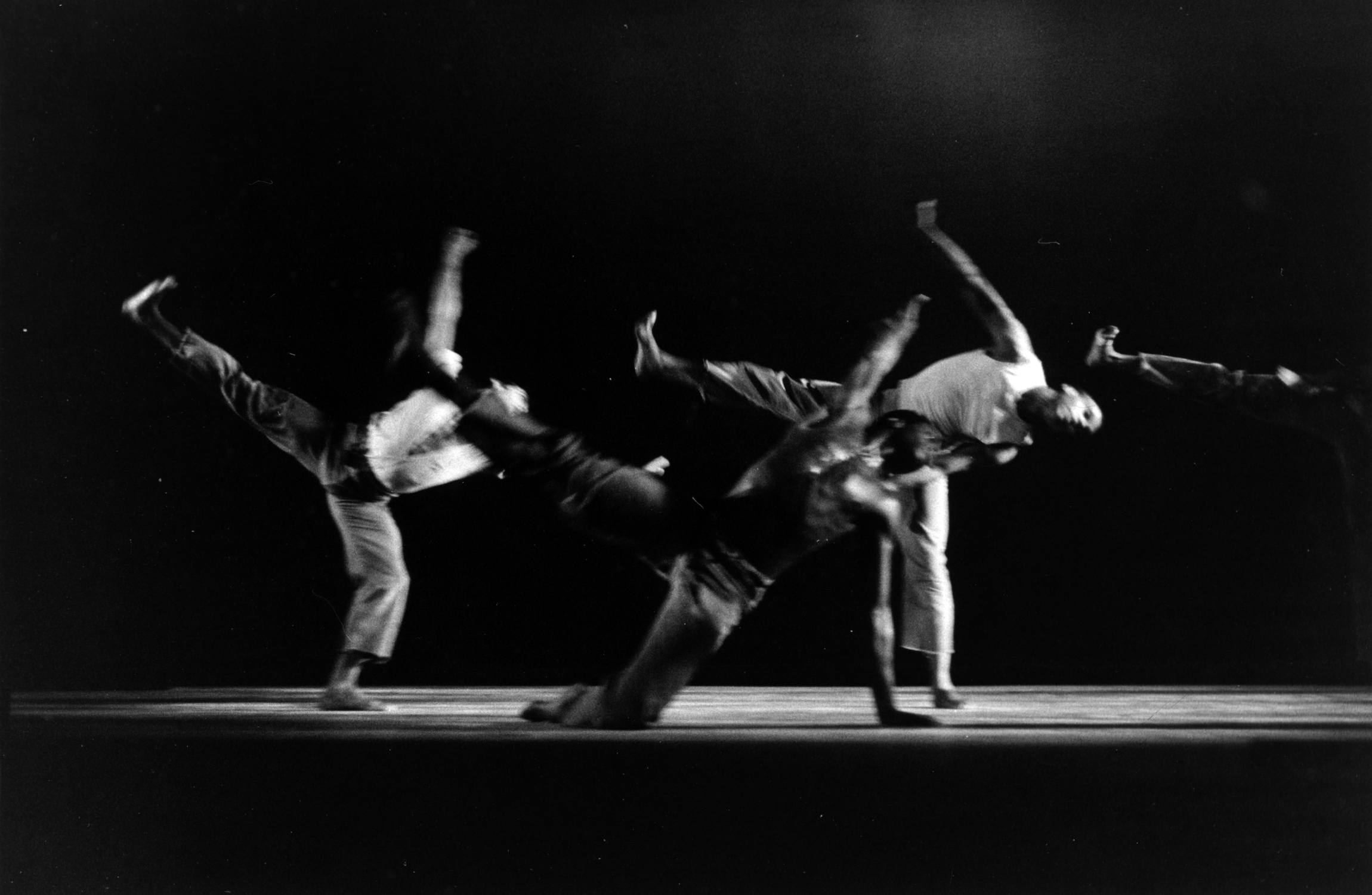

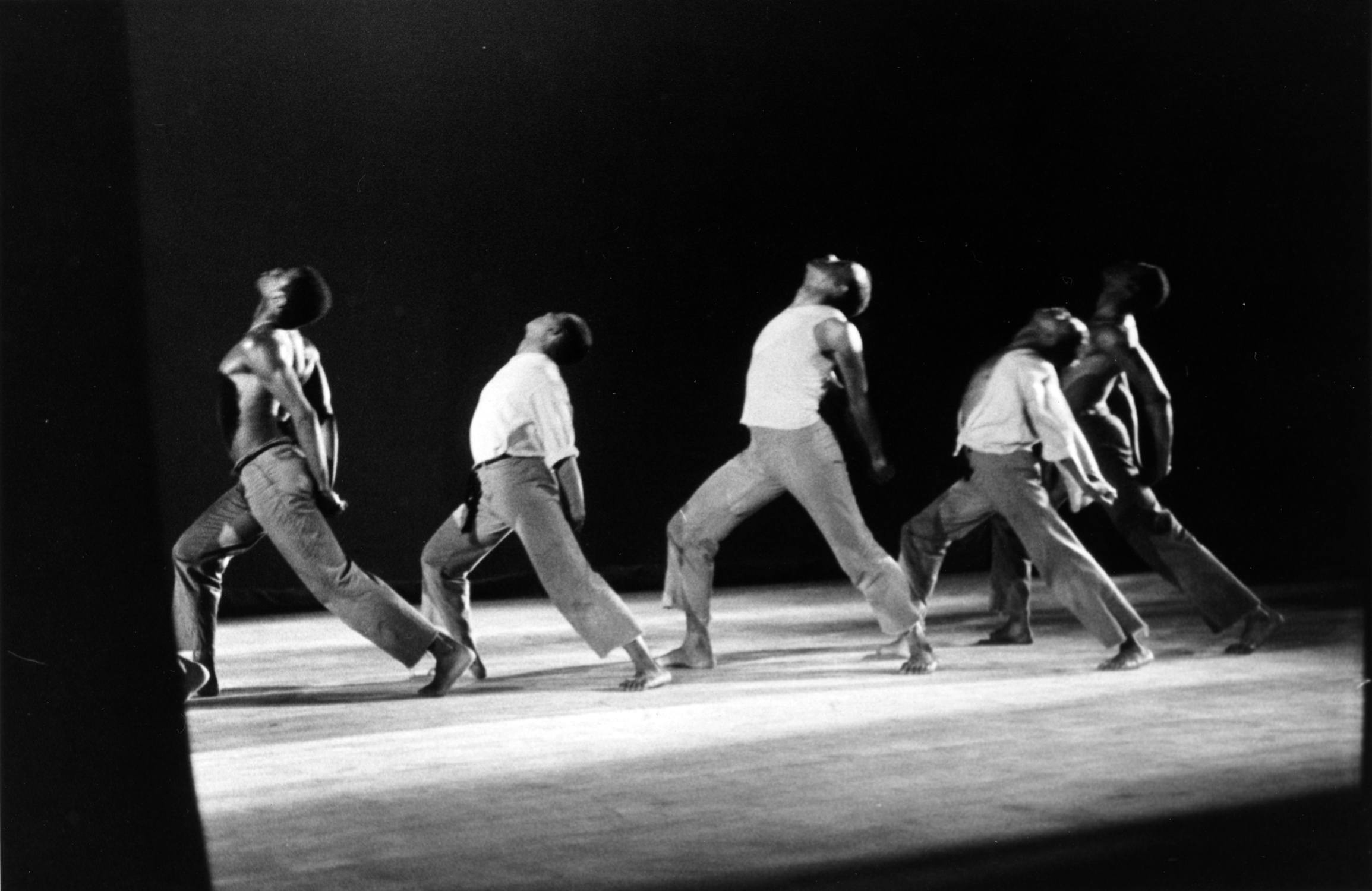

McKayle visited the Pillow for a second time on July 25-29, 1961, and his company consisted of Mary Hinkson, Tommy Johnson, Claude Thompson, William Louther, Don Martin, Charles Neal, and Morton Winston, performing Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder (1959).

The work became one of his signature pieces, and it displayed many of the characteristic aspects of his choreographic style—extremely visceral movement, emotional verity, and dramatic intensity. In his autobiography, McKayle explained the source of the work’s intriguing title as it related to the subject matter, a southern chain-gang, “Rainbow was the prison slang for the tool used to break rock for road beds. The pickaxes glistened as they were swung, sometimes creating their own fleeting rainbows, arching spectrums of color reaching into space and quickly vanishing.”Ibid., p. 115. A program note for the Pillow performance went a step further in describing the prisoner’s situation:

. . . . Always dreaming of their lost liberty, the men think of their women. A young prisoner dreams of his first date, snapping her fingers and full of fun, and then of his loving mother who symbolizes everything good, warm and safe. Another thinks of his faithful wife, who could bring peace and a measure of balance to his troubled world. As the prisoners’ reveries end, they break into a song of defiance, voicing their longing for escape, which they would gain at any cost. Two try to escape, but shots ring out and both fall dead. The others, looking on helplessly, chant: “He had a long chain on, they killed another man, another man done gone.” Program, Jacob’s Pillow–1961 Season.

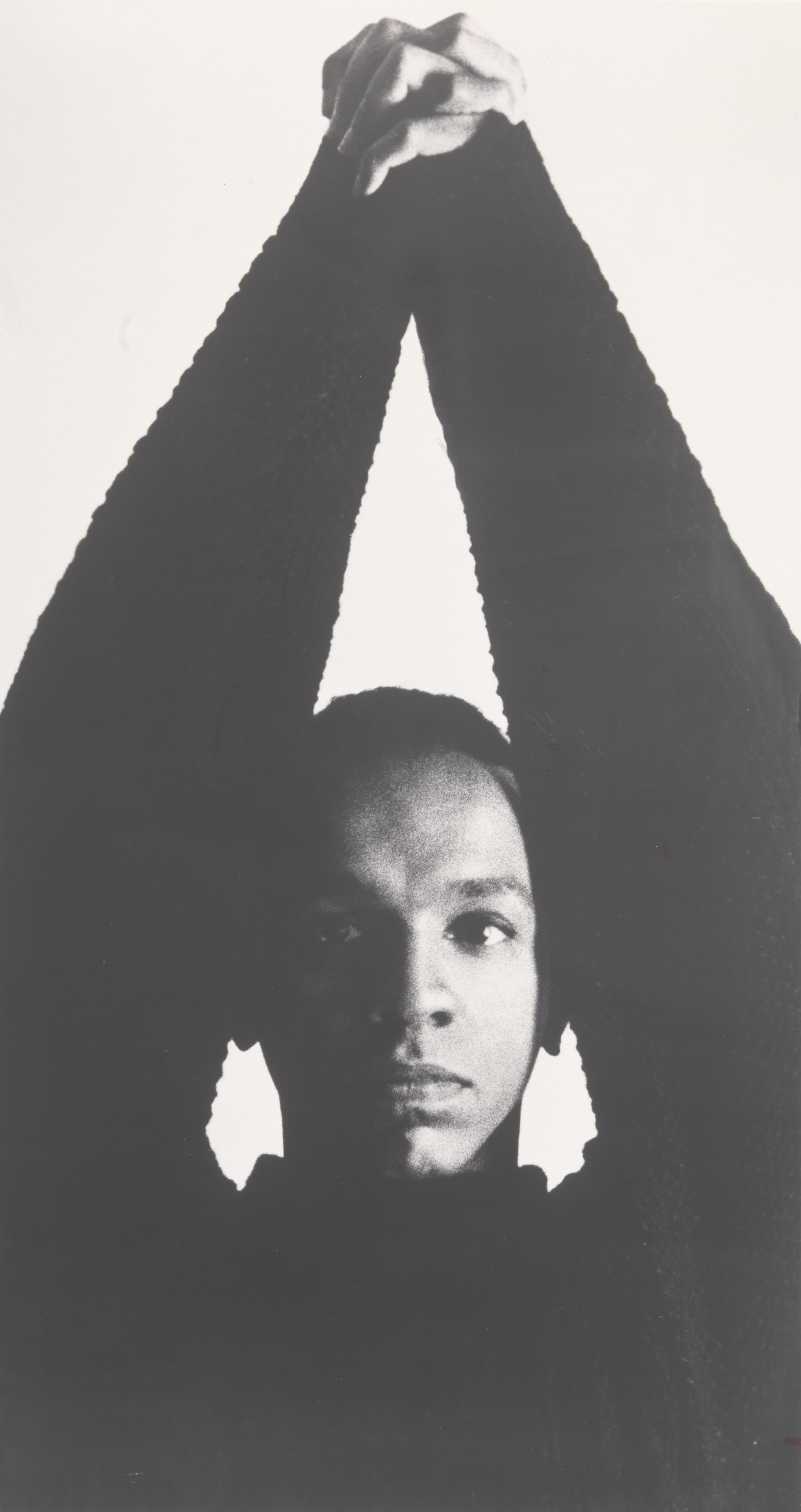

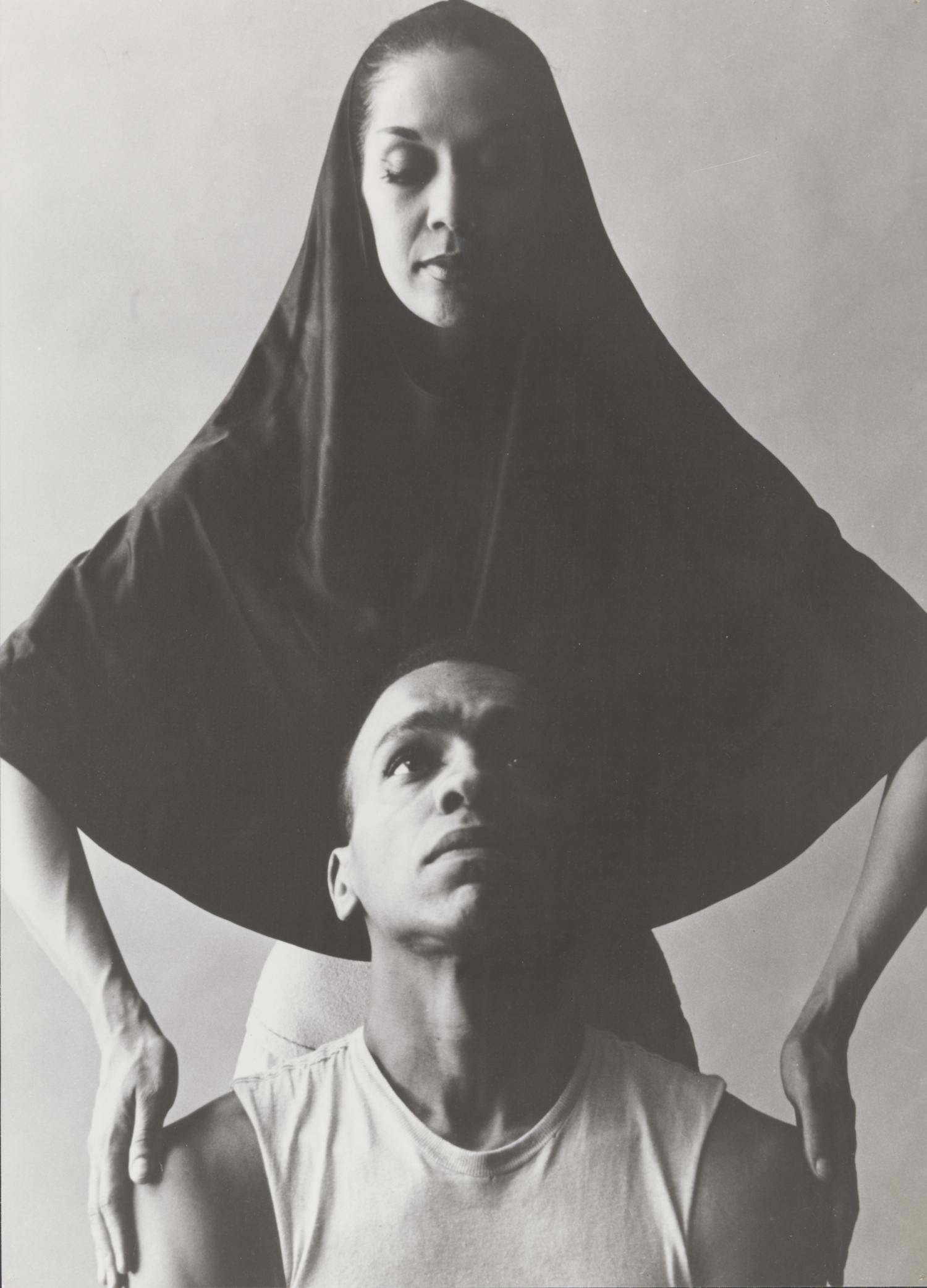

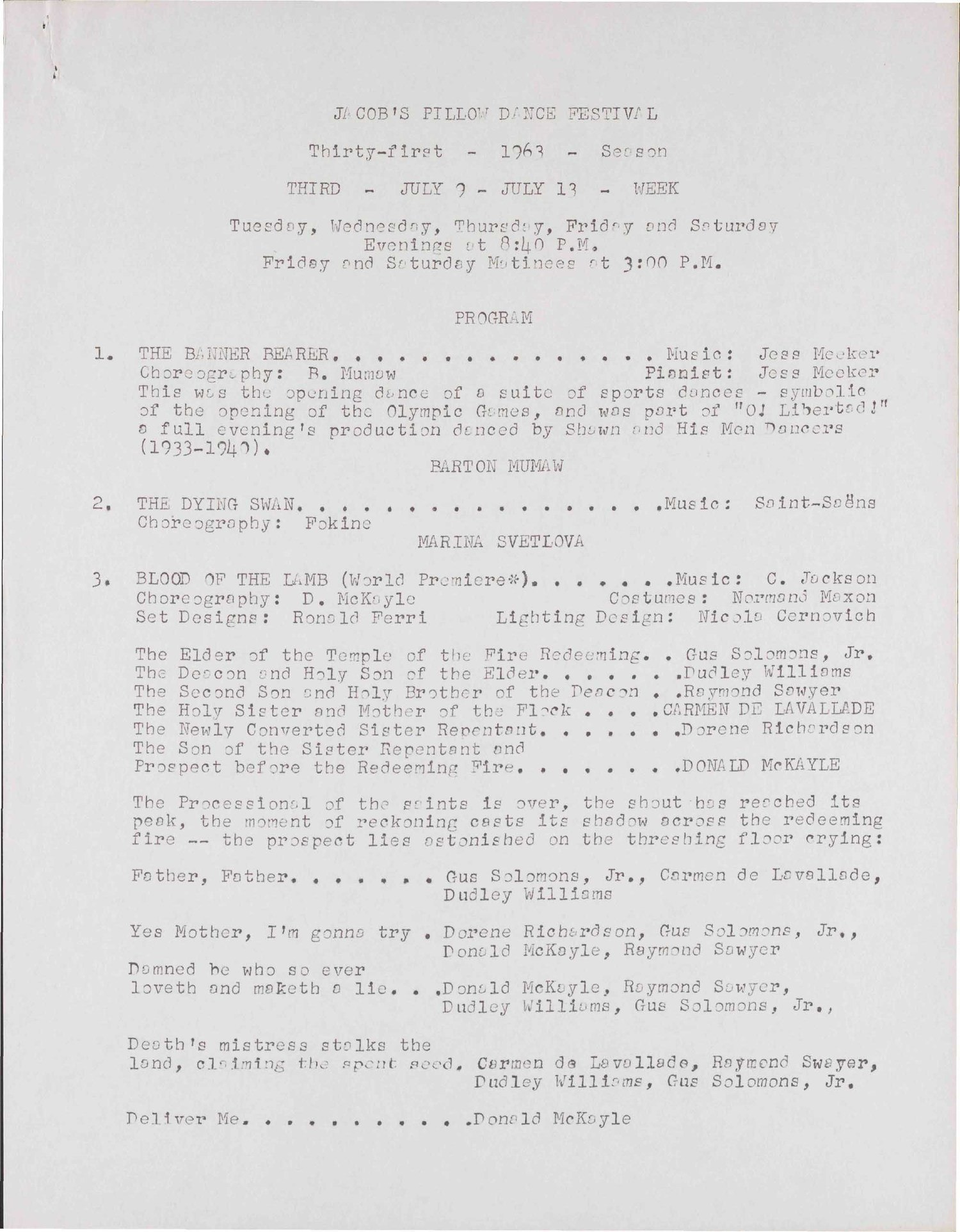

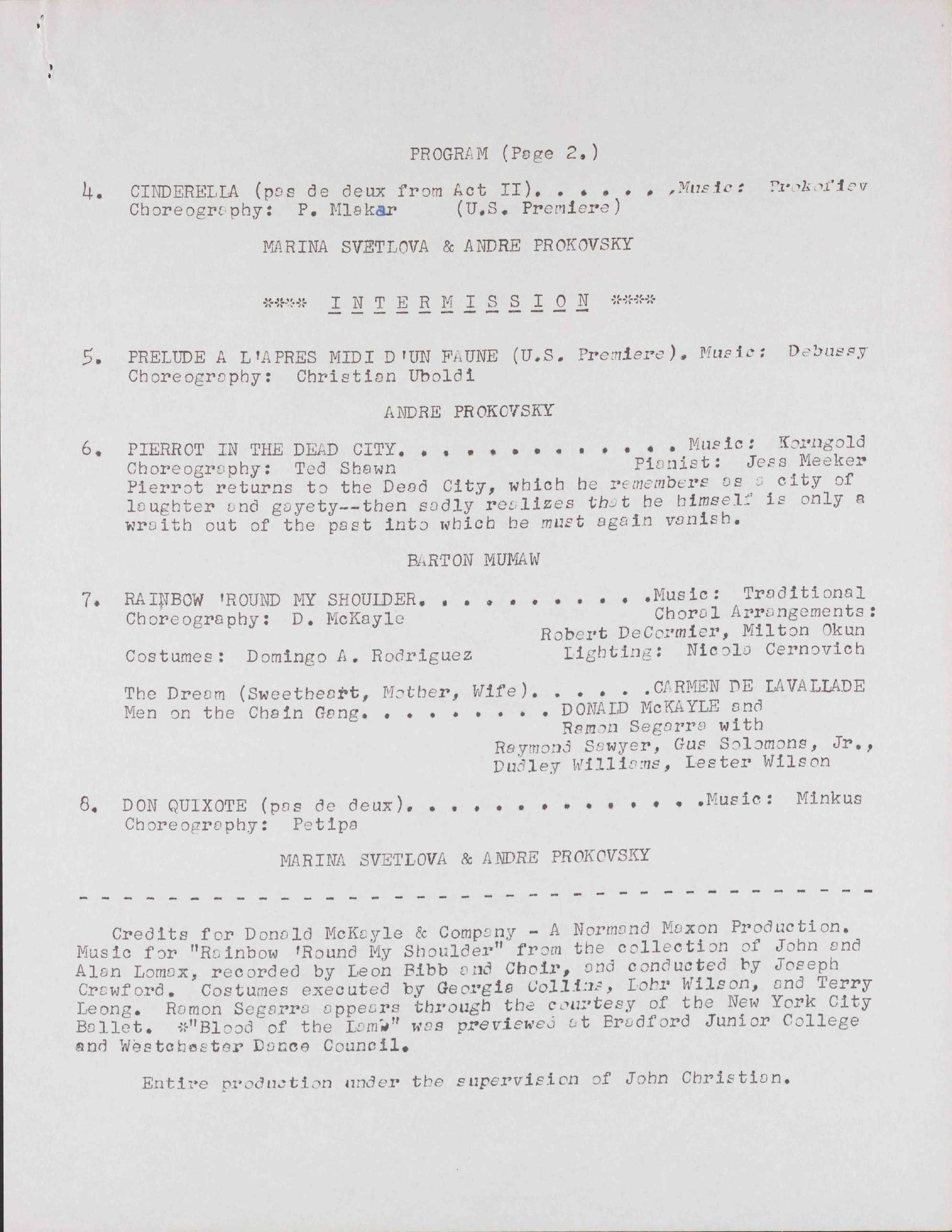

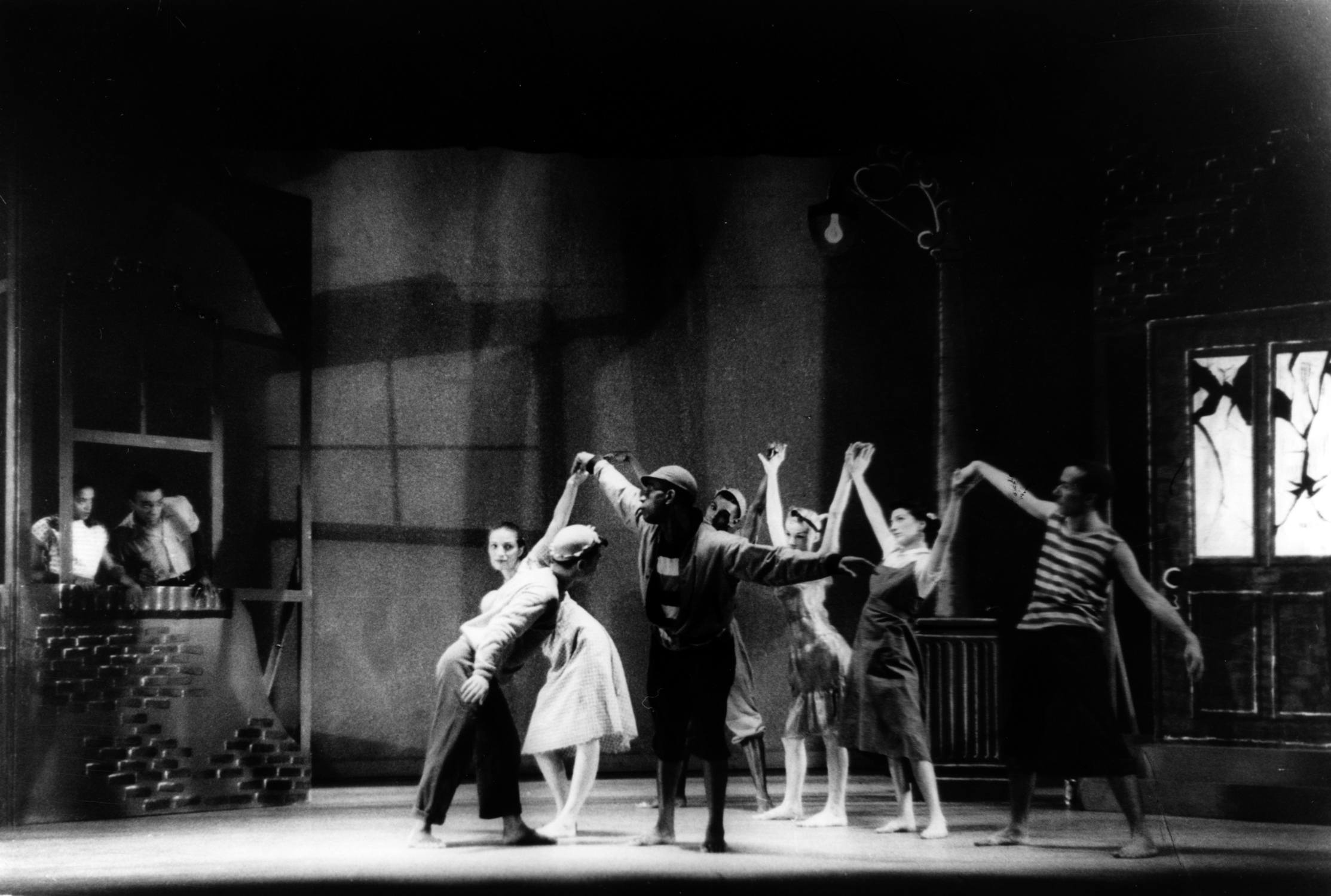

Except for the choreographer himself, the company that McKayle brought to the festival for his third visit, on July 9-13, 1963, consisted of a completely different group of dancers. Among them were Carmen de Lavallade, Dudley Williams, Gus Solomons, Jr. and Raymond Sawyer. The company’s section of the program opened with what was listed as the world premiere of Blood of the Lamb (1963), which McKayle later recounted was “a distillation of impressions from James Baldwin’s novel Go Tell It On The Mountain and drew its characters and setting from the black church.”Transcending Boundaries, p. 149.

That McKayle’s inspiration was drawn from an author whose writings confronted America’s racial complexities at every turn, indicates his consciousness of the social and political realities that were being reflected in African-American art during the 1960s. Baldwin often used the rituals of black churches to symbolize the historical process of African-American lives being tempered in the fires of American racism. The program note for Blood of the Lamb read as follows: “The processional of the saints is over, the shout has reached its peak, the moment of reckoning casts its shadow across the redeeming fire—the prospect lies astonished on the threshing floor crying.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Thirty-first—1963—Season.

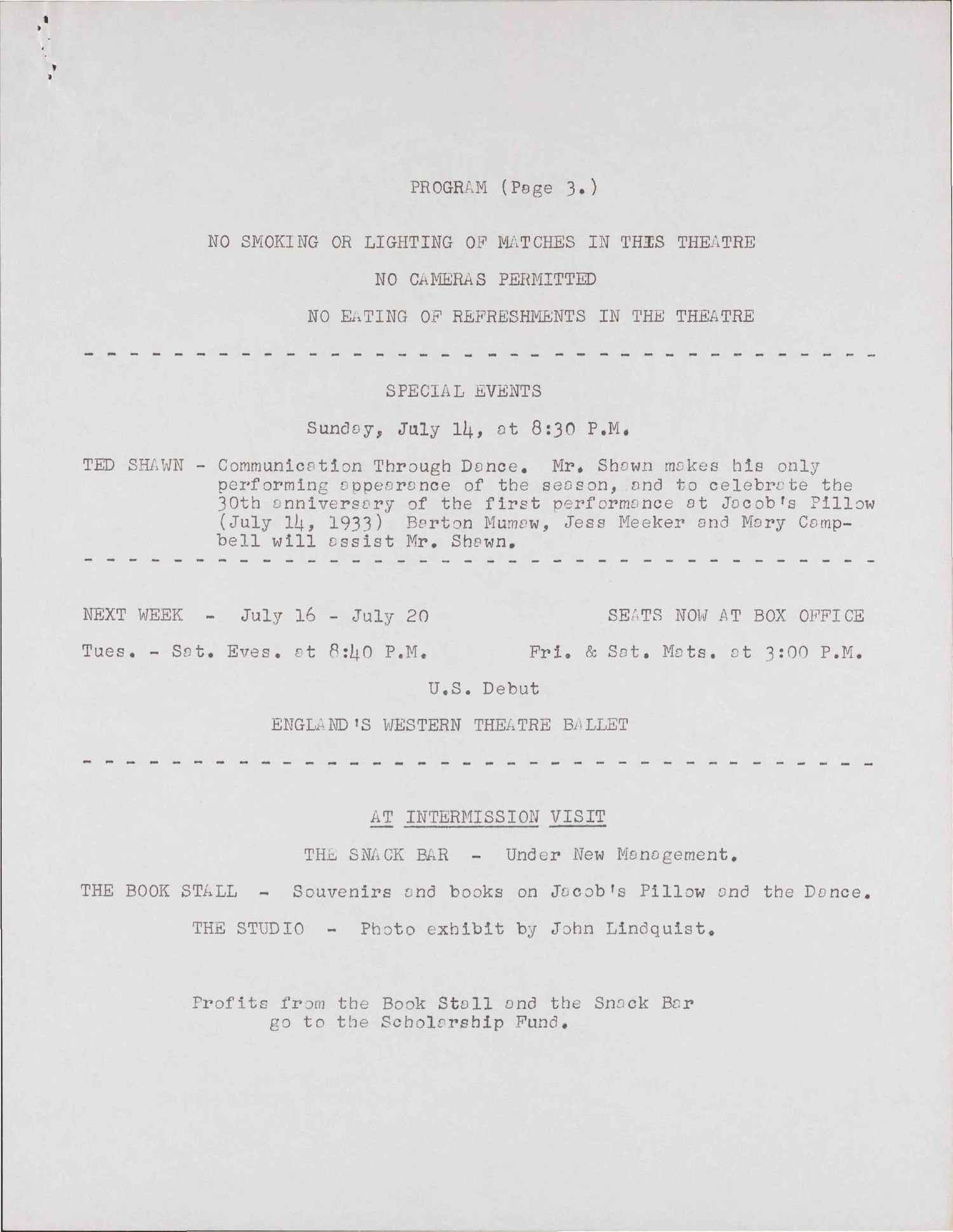

Donald McKayle and his company shared the 1963 concert with Marina Svetlova and Andre Prokovsky who performed excerpts from Cinderella and Don Quixote. McKayle often recounted one of his most painful memories about dancing on the same program as Svetlova, who sprinkled rosin on the stage floor to give her pointe shoes the traction she needed. Of course, McKayle and his men followed her Dying Swan with Rainbow and its choreography that required them to slide on their knees and other parts of their bodies. The solution—they ended up hiding Svetlova’s rosin can after their first encounter with the problem. The other sections of the concert consisted of Barton Mumaw performing two solos, The Banner Bearer, and Pierrot in the Dead City.Ibid.

The female figure in Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder was danced by Carmen de Lavallade, who had first appeared at the Pillow with the Lester Horton Dance Company in July 1953, and she had also danced with Donald McKayle when he replaced Alvin Ailey in the cast of House of Flowers. In Rainbow, her solo sections expressed a range of emotional expressiveness, from the ebullience of a flirtatious girl to the grief of a dying prisoner’s wife.

Later Life

Throughout his career, McKayle maintained a close association with Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, and he engaged in a broad range of activities that made his contributions especially valuable to the dance community there. His work continued to be performed by companies that appeared at the festival. For example, the Limón Dance Company performed his Heartbeats in 1997, Crossroads in 2001, and his Angelitos Negros in 2006. As mentioned before, Cleo Parker Robinson’s company performed Nocturne in 1996. Dayton Contemporary Dance Company performed Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder in 1990. And, the Lula Washington Company performed excerpts from Rainbow in 2006.Various programs from Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Donald McKayle had a multi-faceted career that enabled him to dance in the companies of major artists, eventually form his own internationally-renowned company, and make his mark in the dance world as a choreographer of note. Moreover, in this essay, I have barely mentioned his successful career as a choreographer and a director in the competitive worlds of television shows, Broadway productions, and Hollywood films. In addition, his love of teaching was another facet of his life that always held a special place among his pursuits. As he spoke of this in his own words:

Teaching dance and developing young artists had been a part of my personal interest from my own beginning fascination with the body’s possibilities as a vehicle for expression. I had taught creative movement to children when I was a junior counselor at Camp Woodland before I had any formal experience with dance. I just shared my own joy and found great satisfaction in what came back to me.Transcending Boundaries, p. 271.

He continued, speaking of other places he had taught, “[At Juilliard,] Joyce Trisler, Chase Robinson, and Patricia Christopher . . . attended my classes. Carolyn Adams, Meredith Monk, Beverly Emmons, and Lucinda Childs had been at Sarah Lawrence when I [taught.]Ibid. p. 272,

His remarkable abilities as a teacher became an even more important part of his life after he assumed a professorship at the University of California at Irvine in 1989, and his ongoing work with students—as a technique teacher, coach, and mentor—became a major part of Jacob’s Pillow’s offerings over the years. In addition, he choreographed works for students and set dances from his repertoire on them. His reconstruction of sections of Rainbow became an integral part of the Dance Etudes Project. As stated in a 1994 program, “The Repertory Etudes Project, in its third year, at Jacob’s Pillow, works to preserve the legacy of modern dance by passing masterworks from one generation to the next.” Program, Inside/Out, July 1, 1994.

Another Pillow initiative McKayle played a major role in—along with Joe Nash, and Chuck Davis—was the Cultural Traditions Program inaugurated at the festival in 1998. All three of the artists had been involved in careers that crossed the boundaries of many different dance disciplines, and they also knew firsthand the importance of assuring that the dance of different cultures was acknowledged for its artistic value. The workshops initially focused on the dances of the African diaspora, but they became more inclusive over the years.

Donald McKayle’s career in dance and his contributions to the creative environment at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival tell a remarkable story of his artistic gifts, his perseverance against all odds, and his generous nature. By the year 2000, he had been part of the festival’s life for almost fifty years and had even joined the Board of Directors. That same year, he continued sharing the breadth and the diversity of his experiences with students by teaching and choreographing for Jazz Workshop: Broadway Evolutions. In an interview during that time, he summed up his objective at the workshop, and he also commented on the constantly evolving nature of dance in its many forms, including theatrical, concert, and vernacular dance. Referring to how much things had changed since the festival’s founding, he laughingly commented, “Ted Shawn would roll over. Philip Szporer, Interview.

In retrospect, it is crystal clear how appropriately the title of McKayle’s autobiography, Transcending Boundaries, described his ongoing contributions to Jacob’s Pillow and the world of dance.

PUBLISHED June 2017