Introduction

A man dressed in black hunches over like a fairy tale crone. Half-hidden behind the beaded curtain of his dreadlocks, his face tilts sideways, one ear aimed at the floor. His feet are down there, and he wants to hear what they’re saying. The feet are large and they speak loudly, resonantly, with a concussive intensity that can’t be fully explained by either the metal taps on his soles or the electronic amplification of the wooden platform upon which he dances. The feet tap out the same message again and again, insistently. Then suddenly Glover moves on. For a moment, the scooping of his arms gives his dance a West African air, but then he’s off again, his upper half flailing, his hair flying, his rhythms doubling up as his body turns. Reaching for different tones, he ascends to the tips of his toes, drumming no less powerfully or exactly on those precarious perches. Even up there his face turns downward or to the side. It is the look of someone listening.

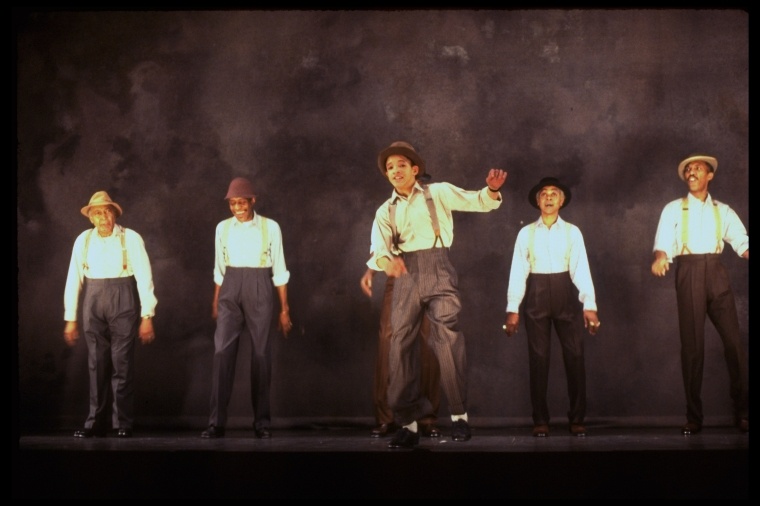

This is Savion Glover during his Jacob’s Pillow debut at the 2002 Gala. His solo dance comes across as a solitary quest, focused on the music. Glover communes with the floor—or, when dancing accompanied, with musicians alongside or behind him. The audience is welcome to witness but is seldom directly engaged. This introversion is a key aspect of Glover’s mature art, one that some viewers find uninviting, off-putting, exclusionary. But Glover has other sides. When he returned to the Pillow in 2005, he brought along friends: a sterling four-piece jazz band, four younger dancers, and two veteran hoofers: Dianne Walker and Jimmy Slyde. The show opened with a gathering:

This is a Hoofer’s Line, a format also known as The Track. Tap dancers standing in a row shout an up-tempo chain-gang chant as their feet rise and fall in a walking-in-place step called the Paddle and Roll, their heavy heels driving a steady locomotive beat. Against the frame of this collective metronome, each dancer on the line steps out in turn to make a percussive statement. “There are rules,” Glover explained in his 2000 autobiography, Savion: My Life in Tap, “but the rules are unspoken, almost secret. The main thing is you got to finish the phrase of the man before you, finish it and then add something of your own.”Savion Glover, Savion: My Life in Tap (New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, 2000) pp.33

The Hoofer’s Line enacts the interplay between tradition and the individual talent, the passing down of tap and its development. For Glover, it is also a ritual of remembrance. In the clip above, Glover’s turn comes last, and what he does is not his own thing but a quotation of the steps and style of the dancer Lon Chaney, who died in 1995. Chaney was the originator of The Track, at least in this form. Chaney was one of the men who taught Glover the rules when he was a barely a teenager. Chaney was one of the dancers who made Glover want to become a dancer himself, when he saw this big bear of a man with a gravely voice pull a pair of tap shoes out of a paper bag and lay down fascinating rhythms—a story that Glover told at his 2005 PillowTalk while holding his own baby son, a boy he had named Chaney.

The Sponge

When he first met Chaney, Glover was already a drummer. Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1973, he had been banging pots and pans since before he could walk. At age seven, he was semi-pro, the drummer in an all-kid quartet, and when his band played for a benefit at Broadway Dance Center in New York, Chaney was on the same bill, joined by the great and mysterious hoofer Chuck Green. Witnessing these two men drumming with their feet made Glover want to become a dancer, a dancer like them. His mother, Yvette, who was raising him and his two brothers without a father, signed him up for classes.

Once he started dancing, Glover danced non-stop: while waiting for bus, while splashing around in the shower, the rhythms just had to come out. Not many years later, in 1984, he was dancing on Broadway, as a replacement in the title role of the long-running musical The Tap Dance Kid. Over the course of some 300 performances, he learned how to be a professional entertainer, how to please an audience. But it was after The Tap Dance Kid closed that his connection to tap grew deeper.

Hired for a tap festival in Rome, he met Dianne Walker, an African-American dancer in her early thirties. She was part of a generation trying to revive the kind of tap that had thrived with jazz in the 1930s and ‘40s but had gone quiet in the decades since. She and others had succeeded in coaxing master dancers out of retirement to pass on their neglected art but had not yet attracted many young African-Americans. Hoping to change that, Walker had invited some talented children to the festival (including Derick Grant and Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, who would turn out to be leaders of tap). But it was Glover, the boy without a father in his life, who attached himself to Chaney and Slyde and the other old men, following them around, hanging on their every word, absorbing all they had to give. They began calling him The Sponge.

For the revue Black and Blue, a throwback production mounted in Paris, Glover was hired to incarnate the next generation, to be the visible inheritor of the tradition embodied by Chaney and Slyde. He spent all his time with those men and the woman he now called Aunt Dianne. Implicitly and explicitly, they taught him the rules of dance, and of life, on and off the Hoofer’s Line. “I saw it wasn’t about pleasing the audience; it was about expressing yourself,” he recalled in his autobiography.Savion Glover, Savion: My Life in Tap (New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, 2000) pp.58 Instead of trying to tap as fast as possible all the time, he relaxed and breathed. “I felt like I was singing what I was dancing.”Ibid., pp.60 He started to imagine adding something of his own.

In 1989, the year that Black and Blue transferred to Broadway, Glover appeared in the first PBS Great Performances: Dance in America special devoted to tap. Not only was he the youngest dancer in the lineup; his was the act that came last, the one nobody else could top, with all the old steps done faster and at a higher pitch and capped with a backflip into splits. The emotional through-line of the program was a link—a lineage reestablished—between him and the tap elders and program’s star, Gregory Hines. Hines was tap’s star of the eighties, bringing the jazz tap tradition back to Broadway and updating it in such Hollywood movies as The Cotton Club and White Nights. Hines’s 1989 movie Tap, like the PBS special, presented Glover as the future. In the film, Hines’s character is a surrogate father to Glover’s basketball-dribbling teenager, a relationship that closely resembled the one the two hoofers had off screen.

In the 1992 Broadway musical Jelly’s Last Jam, Glover played a younger version of Jelly Roll Morton, the title character, who was played by Hines. At one point in the show, the teenaged and adult Mortons engaged in a tap challenge, taking turns and trying to outdo each other. As much as Black and Blue’s Hoofer’s Line, this challenge dance was a ritual, a passing-of-the-torch that Hines and Glover dramatized in all kinds of tap events. “Winning was never in question,” Hines admitted to The New Yorker, presenting Glover as his successor as he now did just about every time he spoke to the press. Glover’s abilities had outstripped his.

Glover was also discovering his own style. It had something to do with the whack and boom of the bucket drummers he met on the sidewalk outside the theater. It had something to do with the hip-hop in his Walkman. He could tap harder and louder than anyone else without raising his feet any higher off the ground, which meant that he didn’t have to get quieter to go faster. Not unless he wanted to. He could do pretty much whatever he wanted in tap.

That included attracting other young people to the art. Since 1991, when he became a regular on Sesame Street, tapping with Big Bird and Elmo, Glover had been a role model to kids, who mimicked the sideways slant of his baseball cap. Now, in his dreadlocks and baggy pants, he made tap seem cool and current. Just as he had tried to dance like Lon Chaney and Jimmy Slyde, dancers his age and younger now aspired to dance like him.

The army of imitators grew with the success of Bring in ‘da Noise/Bring in ‘da Noise, the 1995 Broadway show that he choreographed and starred in. The show used tap to tell a history of tap braided with the history of oppressed African-Americans, a narrative that led to Glover. The show, whose choreography earned Glover a Tony Award, was hailed as a breakthrough, young and raw and contemporary.

Yet Glover always pointed backwards. In a key number in the show, he turned his back to the audience and faced mirrors as he danced to his own voice, demonstrating the styles of Chaney, Slyde, Chuck Green, and Buster Brown, and how their styles fed into his. He resisted the labels “rap tap” and “hip-hop” tap, because he considered himself a hoofer, like those men before him. “It’s only different because it’s now. I’m not changing styles or anything,” he informed the Chicago Tribune. “People think I dance angry,” he told The New Yorker, “but I’m reaching for a different tone.”

In the late ’90s, Glover’s fame and dominance continued to increase. He tapped on Monday Night Football and in a video with the rapper Puff Daddy, who also appeared in Glover’s own ABC special. On another TV special, Glover tapped at the White House, introduced by President Bill Clinton as the “greatest tap dancer of all time” — a judgment that has seldom been challenged in the decades since.

Improvography at the Pillow

The most important context for Glover’s 2005 Pillow appearances is the death of Gregory Hines two years earlier. This surprise loss of a father figure, killed by cancer at fifty-seven, shook Glover. “I’m ready to live another life,” he told the New York Times.Savion Glover in “Bring In da Tapping, Bring In da Singing” by Lola Ogunnaike in The New York Times, December 29, 2003 He settled down and got married. He became a father. In his shows, he often performed with a photo of Hines onstage or around his neck. Still wary of the forced affability associated with the idea of “entertainment” (he preferred to think of his performing as “edutainment”), he started singing a bit, as a tribute to the all-around entertainer tradition of his mentors. “They sang, they danced, they told jokes,” he said to the Times, “and I’m at a point where I want to do that.”Ibid. When in the right mood, he could seem like their heir in this mode, too.

“Improvography,” the title of his Pillow program, was a term coined by Hines to describe a mix of set choreography and in-the-moment ad-libbing. Some numbers for himself and his group of younger dancers—who, in solos, showed off skills commensurate with the superhero T-shirts they wore—featured unison passages in shifting formations. Some of these numbers were set to pop songs, such as Michael Jackson’s “Remember the Time.” In his PillowTalk, Glover explained, as he had in his autobiography, that the generation of hoofers before him hadn’t always danced to the music they partied to; he wanted, in his words, to keep himself and tap “current with the culture.”

Yet the core of the show was Glover alone with the band, improvising to jazz. “My whole approach is like one of a horn player’s,” he told Jane Goldberg in Dance Magazine. “I’m just blowing.”“Savion brings back ‘da Noise” by Jane Goldberg in Dance Magazine, December 2002 He had a particular horn player in mind: John Coltrane, a dead mentor he never met but whose peers he now played with regularly and whose spiritual search through music became a model for his own.

The free-flowing nature of these improvisations can be captured only in clips of some length. The one below starts with a taste of Glover’s singing “The Way You Look Tonight” before he directs the band into Miles Davis’s “Seven Steps to Heaven.” Over in a corner, he kicks into one of his top gears, absurdly fast and clear, spurring the already brisk feel with stamped accents. When the accompaniment grows sparser during the “stop-time” section, his invention is more exposed: wild, wobbly steps generated on the fly abutting rhythmic variations on The Shim Sham, a widely remembered routine from the 1920s.

But throughout the clip, notice how Glover directs the music, conversing with the band members, requesting what he wants, seldom verbally. Notice how they respond. (Sometimes, stomping with elbows akimbo, he looks like a Munchkin, a bit of playfulness that’s also a call for a different groove.) After the song ends, keep watching as he takes his time graciously introducing the musicians, dancing as he does so. This section, soft and loose, makes especially evident how second nature tap is for Glover as a language: he can tap small talk. Much of what he’s doing here is reminiscing. As he chants the phrase “There Will Never Be Another You,” he physically alludes to Hines, Chuck Green (the floating, tightly crossed turn), George Hillman (the wobbly Charleston), and Ralph Brown (the back-on-the-heels traveling step)—paying loving homage to the dead, summoning their spirits by dancing their signature steps. Then he summons Dianne Walker and Jimmy Slyde to the stage, addressing these living elders with even more love and reverence.

Each Pillow performance ended with Stars and Stripes Forever, For Now, an original composition that turns John Phillip Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever” into modal jazz, expressing the equivocation of the altered title by darkening the patriotic melody with a bass ostinato. Four notes down, four notes up, over and over: it sounds ominous, maybe fatalistic, as if it’s saying, “nothing ever changes” while also implying “nothing lasts forever.” At his PillowTalk, Glover explained the number like this: “That’s how the world is. You sort of get it but you don’t. [The group] is together and then there’s war and explosions and then we come back together. We can do that number all night.”

In the following clip, the number and its ostinato have already been going for about ten minutes. All the dancers, after matching the relentless bass with a relentless marching-in-place step, have ceded the stage to Glover. His undershirt is drenched with sweat and he’s in high gear again, blowing like Patience Higgins on sax behind him. The bass figure holds its ground but Glover travels freely, guiding the musicians into hard rock, reggae, Duke Ellington, and “Ding, Dong, The Witch is Dead,” imparting the sense that they might go anywhere. Once more he incarnates Lon Chaney, with heavy-hitting variations on the Paddle and Roll, and eventually, he waltzes the other dancers back in. They end as they began, with that marching in place, turning off one by one as if someone were flipping off switches, until Glover terminates the show with a touch of mordant wit, quoting “Another Ones Bites the Dust” with his feet.

More meaningful than these musical quotations, though, are the dance ones, the insider allusions to tap ancestors. This is always the ostinato of Glover’s dancing, the message it tells over and over, time and again: there will never be another Chaney; there will never be another Hines; there will never be another Slyde, who would die less than three years after this performance. But they live in Glover, forever, for now.

PUBLISHED October 2017