Introduction

The field of somatics was well underway before Philosopher Thomas Hanna coined the term in 1976, as defined by “the body as a lived experience.” The term derives from the Greek word for the living body, “soma,” and is the study of the body experienced from within. Sometimes there may also be an audience present during that experience.

The two practices that have most dominated the dance field are The Alexander Technique, founded by Australian actor F. Matthias Alexander in Melbourne and London in the early 20th century, and later The Feldenkrais Method, founded by nuclear scientist and judo master Moshe Feldenkrais in London and later Tel Aviv, during the mid 20th century.

Other roots of somatics can be traced back to the late 19th-century European Gymnastik movement, which used breath, movement, and touch to direct awareness. François Delsarte, Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, and Bess Mensendieck encouraged a kind of inside-out expression.

Americans also made significant contributions. Mabel Elsworth Todd’s classic text, The Thinking Body, introduced dancers to the role of the mind in dance training in 1937. And her student, Lulu Sweigard, developed “ideokinesis,” which is fully entrenched in dance training in the use of imagery. In fact, various somatic practices are now so embedded in contemporary dance training, the “somatic seep” is a real phenomenon.

Yet, dancers and others still struggle with a working definition of the field. In a 2018 PillowTalk about Jerome Robbins, Robbins and Somatics scholar Hiie Saumaa gives a vivid description of Somatics and how it penetrates more than movement practices, and actually influences her research.

Saumaa makes a marvelous case for a broad definition of the somatic experience. That said, dancers have always been deep explorers of the body as a lived experience. Consider the group of American women who came from the field, including Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen (Body-Mind Centering), Emilie Conrad (Continuum), Joan Skinner (Skinner Releasing), Elaine Summers (Kinetic Awareness), Susan Klein (Klein Technique), and Judith Aston (Aston-Patterning).

If we examine the values of the somatics field—the primacy of bodily sensation, the expression of pleasure in movement, the use of efficiency in action, a connection to everyday human movement—then we can see a multitude of connections between the field and what’s happening on contemporary dance stages. Choreographers and dancers need no certification in a codified method to manifest these values.

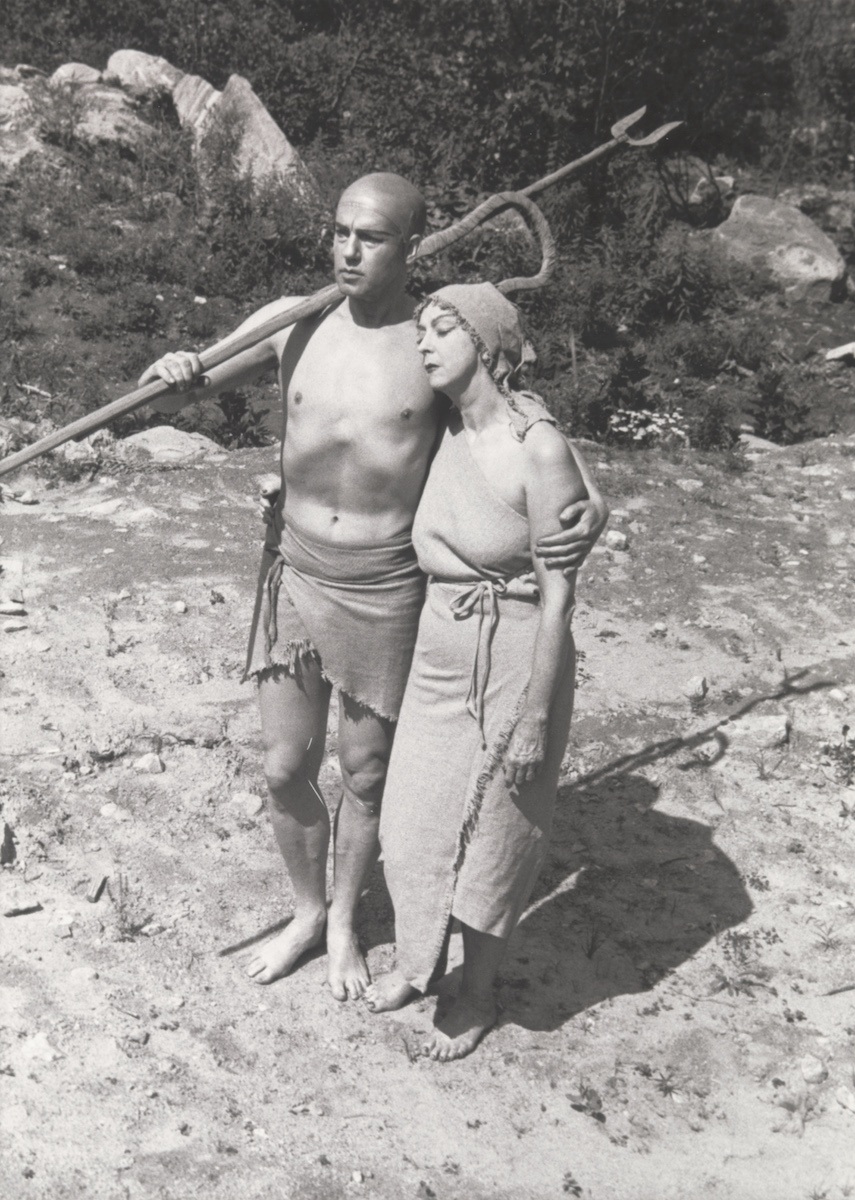

At Jacob’s Pillow we can start with founder Ted Shawn, who saw connecting to the flesh as the first step in training a dancer. Even in his early years running the Denishawn school with Ruth St. Denis, he included training in the Delsarte Method, an early iteration of a somatic practice founded by French musician and educator François Delsarte in the mid-19th century.

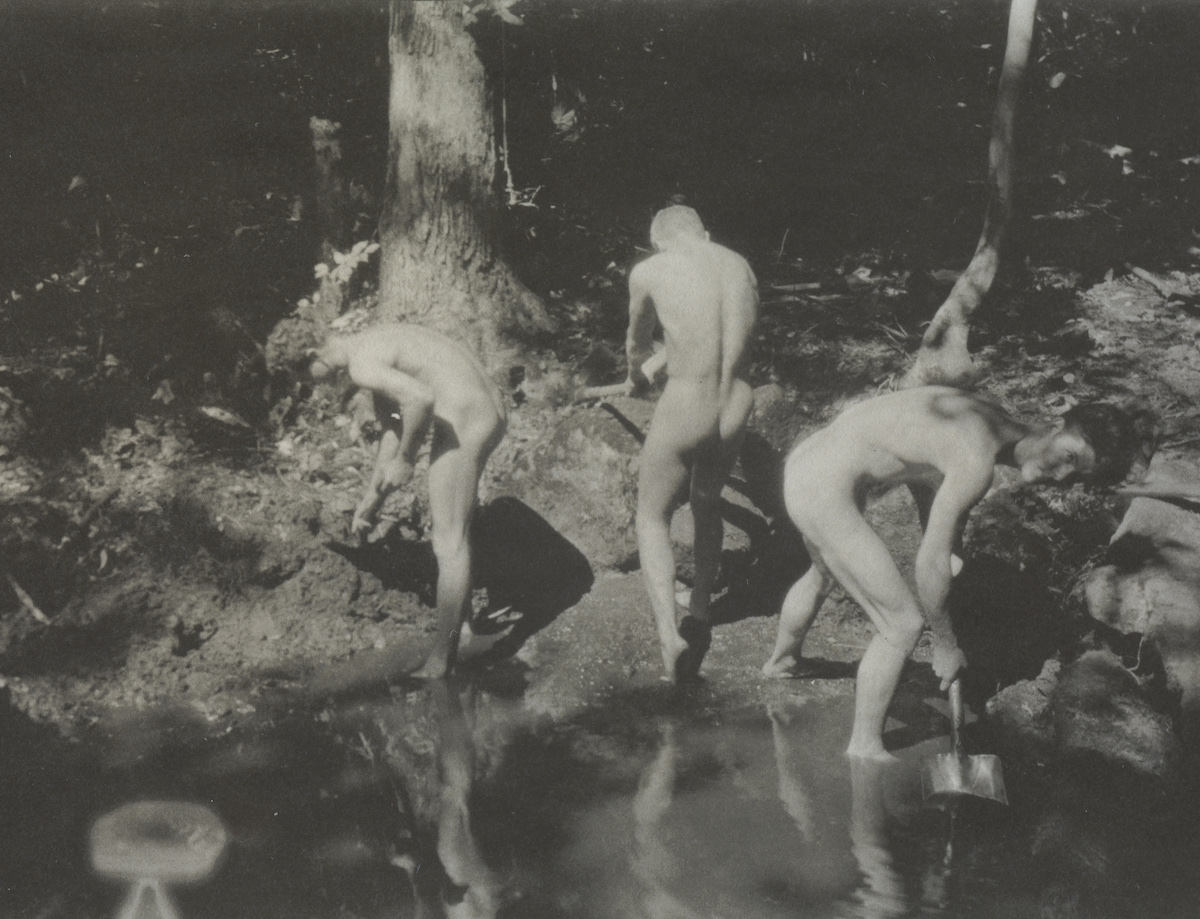

When Shawn moved his operation to Jacob’s Pillow to develop his all-male company, the Men Dancers built the place from the ground up, as well as growing their own food. It was the Depression, and they needed to eat and have shelter, but Shawn considered physical labor an essential training practice for his men dancers.

Adam Weinert recreated many of Shawn’s training practices, which included hard work in the garden, as part of his embodied research for a 2016 Doris Duke Theatre production entitled Monument. He mentioned in a 2015 PillowTalk that he did indeed feel more grounded in his dancing from his work on a farm, which led to his ongoing body of work recreating Shawn’s dances.

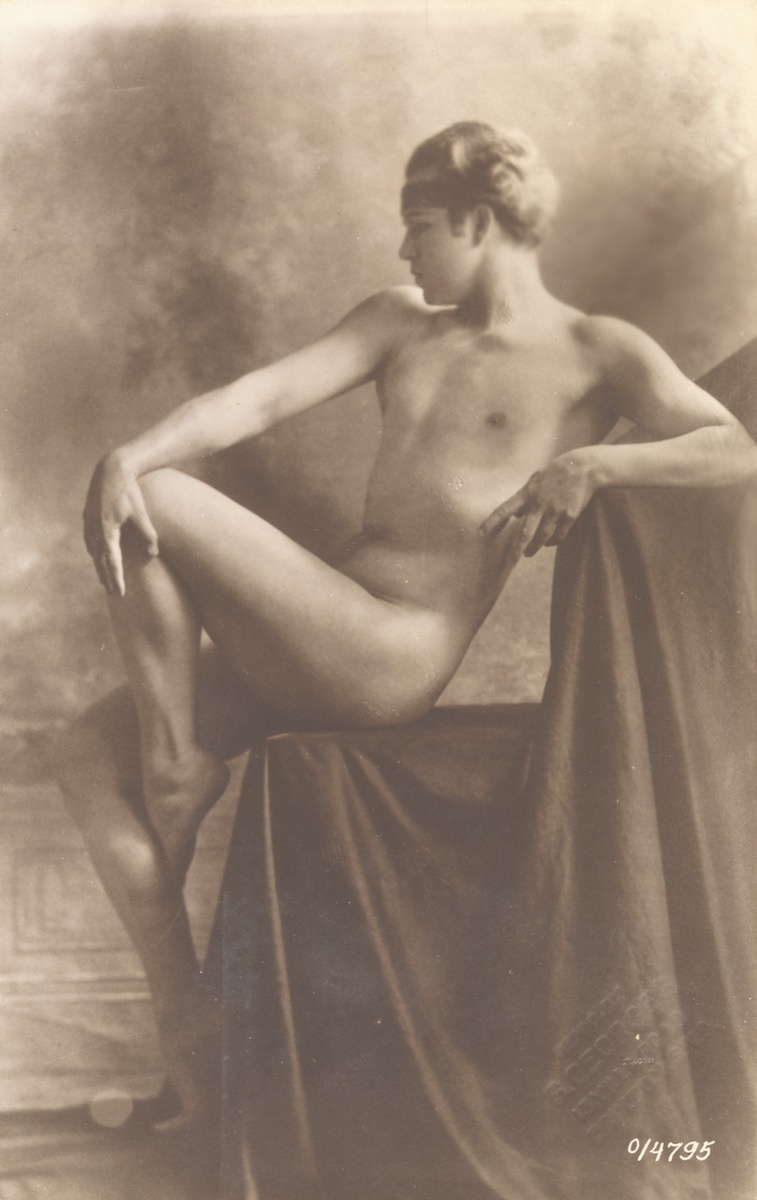

Shawn was bold when it came to showing off his body and the bodies of his male dancers. From the tea events where the men dancers served tea and sandwiches dressed in a pair of trunks to choreography which highlighted the male form, Shawn was consistently interested in the body in the natural landscape. Decades later Eiko continued that tradition in her own aesthetic with Eiko at the Pillow, a commissioned work on the Pillow grounds.

Pleasure in the Body

A consistent thread in somatic reasoning is an unapologetic appreciation of the body. Experiencing pleasure is often relegated to a private or sexual domain. Yet this internal sensing, where we as audience members act as voyeurs of a sort, has been around a lot longer than the somatic label.

Consider Jerome Robbins’s Bach ballet, A Suite of Dances, first performed by Mikhail Baryshnikov. Premiered March 3, 1994, as part of the the White Oak Dance Project at the New York State Theater, the ballet was performed by Daniel Ulbricht as part of an all-Robbins program presented by Stars of American Ballet in August, 2018.

Performed with an onstage cellist, A Suite of Dances revels in the camaraderie between the cellist and the solo dancer. But there is another relationship going on—between the dancer and his internal sensations. It’s subtle, almost as if the dancer gets lost in his own performance, forgetting about the rest of us. Robbins was a master of creating ballets that often turn inward, toward the other dancers on stage as in Dancers at a Gathering, or even deeper into their own sensing such as Afternoon of a Faun.

Saumaa discovered in her research that Robbins studied with an underrecognized dance and somatic educator, Alys Bentley, who was a pioneer in expressive movement forms and Dalcrozean eurhythmics. Robbins’s internal focus is subtle and it comes and goes, creating an vibrant dynamic between attending to the audience and one’s own delicious movement.

We can’t talk about reveling in the body without bringing in the Israelis, most notably Ohad Naharin, whose groundbreaking technique known as Gaga has influenced a generation of dancers and choreographers. Naharin discovered that dancers need another entry into their moving bodies aside from traditional training, a method to mine something more primal in the moving body.

Naharin gives a vivid description of Gaga in a 2018 PillowTalk when the Batsheva Young Ensemble was performing in the Ted Shawn Theatre.

And the Batsheva Young Ensemble performance of Naharin’s Virus offers a terrific example of sensual inner focus. Here we witness the dancers having an experience that is ravishing for both audience and performer. The focus is inward, yet the choreographer’s eye points outward. Virus is a key example of the performability of somatic concepts, as there exists a deep virtuosity in the dancers’ internal sensing.

Jerusalem-born Sharon Eyal takes this cathartic bodily reveling a few steps further in her club aesthetic-based piece House, performed at the Pillow in 2013. Eyal, a former muse, dancer, and choreographer at Batsheva, founded her own company known as L-E-V in 2013 with Gai Behar. Here the experience is otherworldly, approaching the cathartic.

Efficiency in Action

Somatic practitioners value efficiency and consider it an important neuromuscular concept to practice in order to maintain health and well-being. Efficiency, a core principle of the Alexander and Feldenkrais work, brings a different set of gifts to the performance experience. It’s visually alluring in a haunting way. The Israeli choreographer Roy Assaf brought two of his works to the Pillow in 2017. Both offer prime examples of the sure beauty of efficient movement. In Assaf’s deceptively minimal duet with Hadar Younger, Six Years Later, there’s a slipperiness to the movement, where effort appears invisible, and a palpable bodily connection between the two dancers. They move as if they share a central nervous system, which is curiously a familiar theme in most one-on-one somatic therapeutic work.

Assaf’s trio for three men, The Hill, performed by Igal Furman, Avshalom Latucha, and the choreographer, displays a similar efficiency, but with considerably more fervor.

Exploration and Novelty

Another tenet of Somatics is to value novelty, exploration and doing things in a new way. Jacob’s Pillow Award winner Liz Gerring’s expansive dances come to mind. She is certainly also a master of efficiency in her spare but stunning works. Gerring strips movement down to its essential components, eliminating unnecessary flourishes, so that we experience momentum and stillness in an arresting simplicity. Yet, there’s also a wonderful twisting of habitual patterns. Nothing is as expected, from the movement to the entrances and exits. Gerring employs novelty at every level.

As the practice of dance employs a near endless examination of the body in motion, choreographers will remain at the forefront of the somatics field. Be it ease of movement, turning the ecstatic experience of internal sensing outward, or pushing the form to new heights, somatic principles will continue to charge dance stages with vital new ideas.