Introduction

Dancer/choreographer Asadata DaforaAsadata Dafora’s name is often written as Asadata Dafora (Horton) or Asadata Dafora Horton, as a way of acknowledging his family’s name going back several generations. Dance historian Marcia Ethel Heard traces the Horton family’s history in her detailed Ph.D. dissertation, Asadata Dafora: African Concert Dance Traditions in American Concert Dance. was born in Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa in 1890, and his middle-class upbringing, patterned on British colonial models, figured prominently in his cultural development. This is not to say that his early life was devoid of exposure to the traditions of the different ethnic groups of Sierra Leone. When recounting stories of his childhood to an interviewer in later years, he remembered how he was fascinated with the lives of people who lived outside of his Westernized environment. At a young age, he would leave home without permission to explore the countryside and observe the rituals and festivals of villagers who maintained older traditions. Margaret Lloyd, “Dancer from the Gold Coast—Part II,” Christian Science Monitor, June 9, 1945, p. 5.

Dafora continued to explore indigenous cultures when he traveled through West Africa as a young man, immersing himself in the music, dance, and folklore of different ethnic groups. His studies laid the foundation for his later artistic work, and they also contributed to the multicultural component of that work. In this respect, he shared an element that can often be found in the work of the black artists who pursued careers on Western concert stages. Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Geoffrey Holder are only a few artists who followed similar paths.

When Dafora arrived in the United States in 1929, his first performance was as a concert singer in Harlem. No doubt, his efforts in that direction were shaped by childhood influences. His mother was an accomplished musician who had trained in Europe, and he grew up listening to and performing different types of Western music on a daily basis.Marcia Ethel Heard, Asadata Dafora: African Concert Dance Traditions in American Concert Dance (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1999), p. 60. As a young man, he had also traveled to Europe and studied opera at Milan’s La Scala Opera House, where he appeared in minor roles in several productions, notably L’Africaine and Aida. Ibid. p. 64. Those were additional experiences that contributed significantly to his rich multicultural perspective on the arts.

After his brief appearances as a concert singer in Harlem, Dafora began to refine and clarify the artistic objectives he had been formulating for some time. He wanted to present the music, dance, and dramatized folklore of West African cultures in a theatrical form to show American audiences that those were artistic contributions worthy of being appreciated in their own right. His art would become a keystone in his overarching objective of declaring the beauty, dignity, and humanistic values of black people. This was not an easy task in America during the 1930s, because audiences were accustomed to portrayals of African people—in literature, film, and popular culture—that showed them to be “savages” who were only capable of engaging in the basest of human activities. Such images could be traced back to the Enlightenment thought of 18th century Europe, and they also underpinned the rationale for the centuries-long slave trade. As a child of colonial Europe, Dafora was well aware of the kind of racial prejudice he was up against, but he was also gifted with an abiding humanism and optimism that encouraged him as he set out to pursue his goals.

Production Company

Dance historian Marcia Heard underscores the importance of 1933 as a year when Dafora took major steps toward achieving his goals, “Dafora had established his own production company, the African Opera and Dramatic Company, and a dance company, Horton’s Dancers. With his production company and dance company, Dafora produced his first full length opera, Zoonga. It met with moderate success in Harlem.”Ibid. pp. 77-78. However, it was Dafora’s next production that established him as a critically-acclaimed artist on the New York dance scene and as an individual whose work would contribute to the development of generations of black dance artists that presented the cultural gifts of Africa to the world.

Dafora had established his own production company, the African Opera and Dramatic Company, and a dance company, Horton’s Dancers. With his production company and dance company, Dafora produced his first full length opera, Zoonga. It met with moderate success in Harlem.”

I have written elsewhere of the immense popularity of Kykunkor or the Witch Woman, which opened in May of 1934 and became Dafora’s most successful production during his early years in America. Sparked by a positive review by John Martin of the New York Times, impressive audiences began to attend the dance-opera at the Unity Theater, a small performance space on East Twenty-Third Street in New York City. John Perpener, African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Chicago and Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001), p. 111. Martin effusively described Kykunkor as “one of the most exciting dance performances of the season.”John Martin, “Native Cast Gives African Opera,” New York Times, May 9, 1934.“… one of the most exciting dance performances of the season.” Not only did his critical imprimatur stimulate interest in Dafora’s work, it also forwarded the artist’s objective—to prove that the art and culture of Africa was equal in importance to that of the world’s other cultures.

Of Course, Kykunkor drew some negative reviews that may have revealed more about critics’ prejudices and preconceptions than they did about the performance, but those were more than balanced by the positive comments that praised the performers and the theatrical impact of the material itself. Critics were amazed by the propulsive energy of the dancing, and they were overwhelmed by the polyrhythmic power of the drummers. Based on his years of research, Dafora displayed a genius for bringing authentic representations of African art and culture to the Western proscenium stage for the first time.

Part of the appeal of Kykunkor was in Dafora’s staging of a folktale he had encountered during his travels through West Africa when he was a young man. The story centered on the betrothal of Musu Esami, a village maiden, to Bokari, a suitor from a neighboring village.Musu Esami was performed by Francis Atkins, an African-American woman, and Bokari was performed by Asadata Dafora. After their wedding ceremony begins, a rival for the maiden’s hand has a Witch Woman cast a spell on Bokari who falls to the ground unconscious. The distraught villagers try different ways to revive Bokari, and they eventually call on a Witch Doctor to intercede. His incantations are successful, Bokari is revived, and the couple’s wedding celebration proceeds. The narrative presented many opportunities for Dafora to create interludes for vocal and instrumental music, a variety of dances, and several dramatic vignettes that propelled the story along.

In other writings, I have speculated about the confluence of Dafora’s African and European experiences and the similarities between Kykunkor and some romantic and classical European ballets. Wedding celebrations play a central role in Dafora’s work, as they do in many nineteenth-century ballets; the abrupt arrival of witches and demons is a dramatic convention used in both; and the use of divertissement—essentially excuses for dancing—is prominent in both.Perpener, African-American Concert Dance, p. 110. On the one hand, these parallels may be due to Dafora’s multicultural experiences that I spoke of earlier. On the other hand, the similarities may be due to the fact that diverse cultures of the world seem to share similar themes that run through their myths and their folklore, and those in turn inform their artistic expressions. To answer my own questions concerning these matters, I end up believing that both factors were at work in Dafora’s case. A work like Kykunkor drew on his multicultural background, and it was also influenced by universal themes that appear in storytelling around the world.

During the ten years prior to his appearance at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Dafora made remarkable progress toward his artistic, humanistic, and sociocultural goals, and his successes would certainly have been noticed by Ted Shawn, a man passionately interested in the dance of different cultures, and one who kept his finger on the pulse of the diverse dance activities in New York City.

An Auspicious Pillow Debut

Dafora’s performances at the Pillow took place on August, 6, 7, and 8, 1942, the first year of the festival as we know it today. Shawn had originally purchased the site—an old farmstead near Lee, Massachusetts—in 1931, as a summer home for himself and his all-male dance company. For years, it served as an artistic retreat where the group could concentrate on choreographing and rehearsing new works; and, as Norton Owen, Director of Preservation at the Pillow, notes, they also began a tradition of inviting locals from the surrounding area to informal presentations: “It was in 1933 that the seclusion of Jacob’s Pillow would forever become a memory, as Shawn first decided to open the doors to the public for weekly lecture-demonstration. With admission initially set at 75 cents, audiences were invited to listen to Shawn speak for twenty minutes, followed by a twenty-minute classwork demonstration and ending with two ensemble dances and two Shawn solos.”Norton Owen, A Certain Place: The Jacob’s Pillow Story (Becket, MA: Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 2002), p. 9.

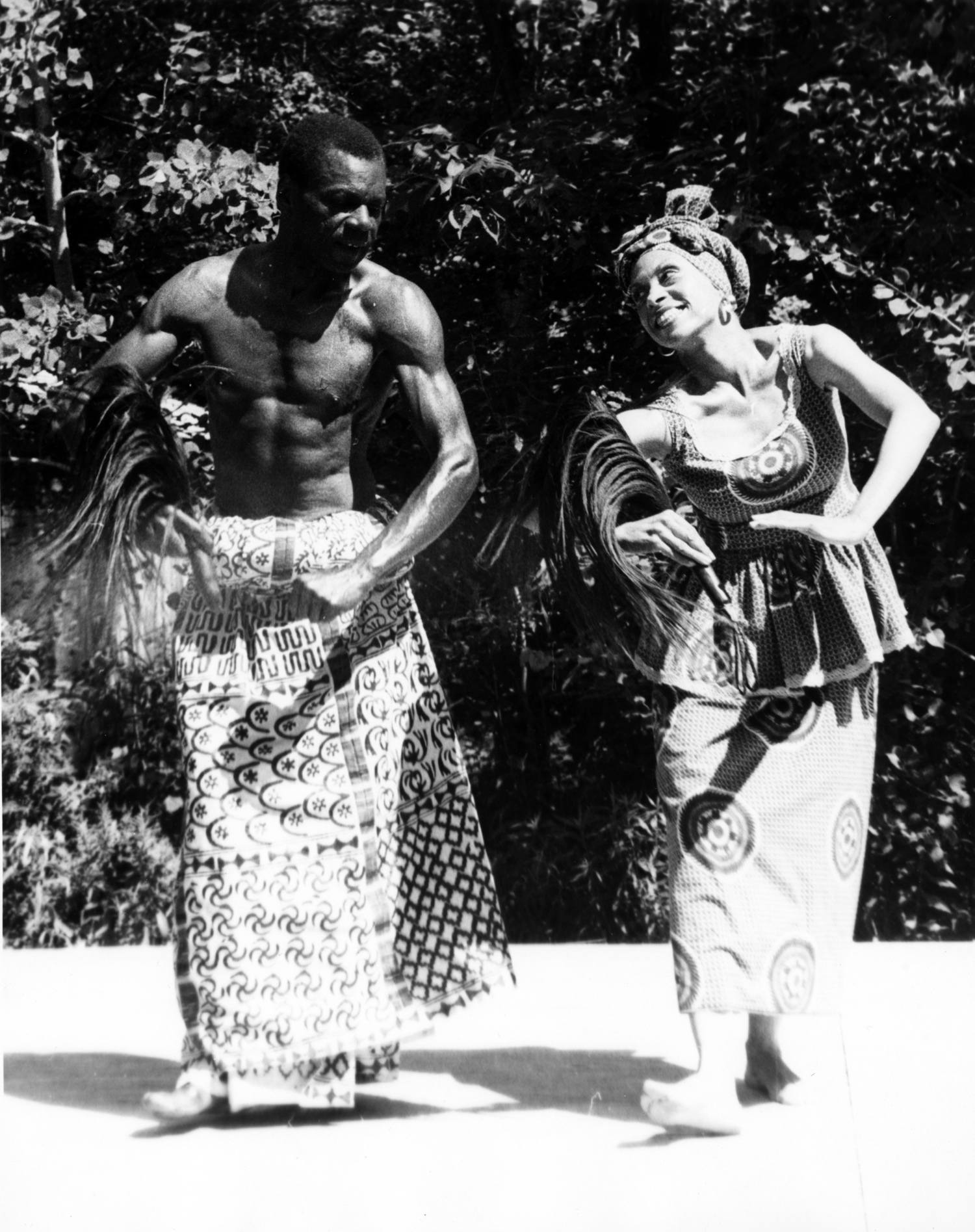

Shawn disbanded his dance company in 1940, and it seemed for a moment that his financial situation would necessitate the sale of the property. However, through a series of interventions by friends and other supporters, the property did not have to be sold; instead it eventually came under the control of a board of directors that supported Shawn’s vision of an ongoing festival and a school.Ibid., p. 12. That vision included a new theater that was completed just in time for the August, 1942 concert that included Asadata Dafora along with one of his dancers, Randolph Sawyer. They performed in the first section of the program titled Shagola Dances of West Africa. Shagola Aloba was the name that Dafora had adopted for his large ensemble of dancers, drummers, and singers as early as 1934. One wonders why he only appeared with only one other performer and two drummers on such an important occasion as the first season of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival and the opening of its new theater. However, we can speculate that the ongoing financial insecurities of dance companies—then as now—may have been the reason Dafora could not afford to gather a larger group at the time.

The dancers appeared in alternating solos, and the printed program included the ethnic group attribution of each dance after its title. Sawyer began with Spear Dance (Timeni Tribe); then Dafora performed Courting Dance (Timeni Tribe);” followed by Sawyer in Challenge Dance (Kru Tribe); closing with Dafora in Jingle Dance (Mandingo Tribe).Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Theatre—Season 1942—Fifth Week. In these dances, the two performers introduced Pillow audiences to the elements that distinguished West African dance from that of European cultures. Among these were the bent-kneed, grounded movement that privileged the body giving in to gravity; the symbiotic percussive interplay between dancers and drummers; and the isolated articulation of different body parts, particularly the pelvis and the hips. Many of the audience members at Jacob’s Pillow—like many of those in New York City eight years earlier—were seeing authentic versions of these elements clearly delineated for the first time on a theatrical stage. This, no doubt, added to the excitement that surrounded those occasions.

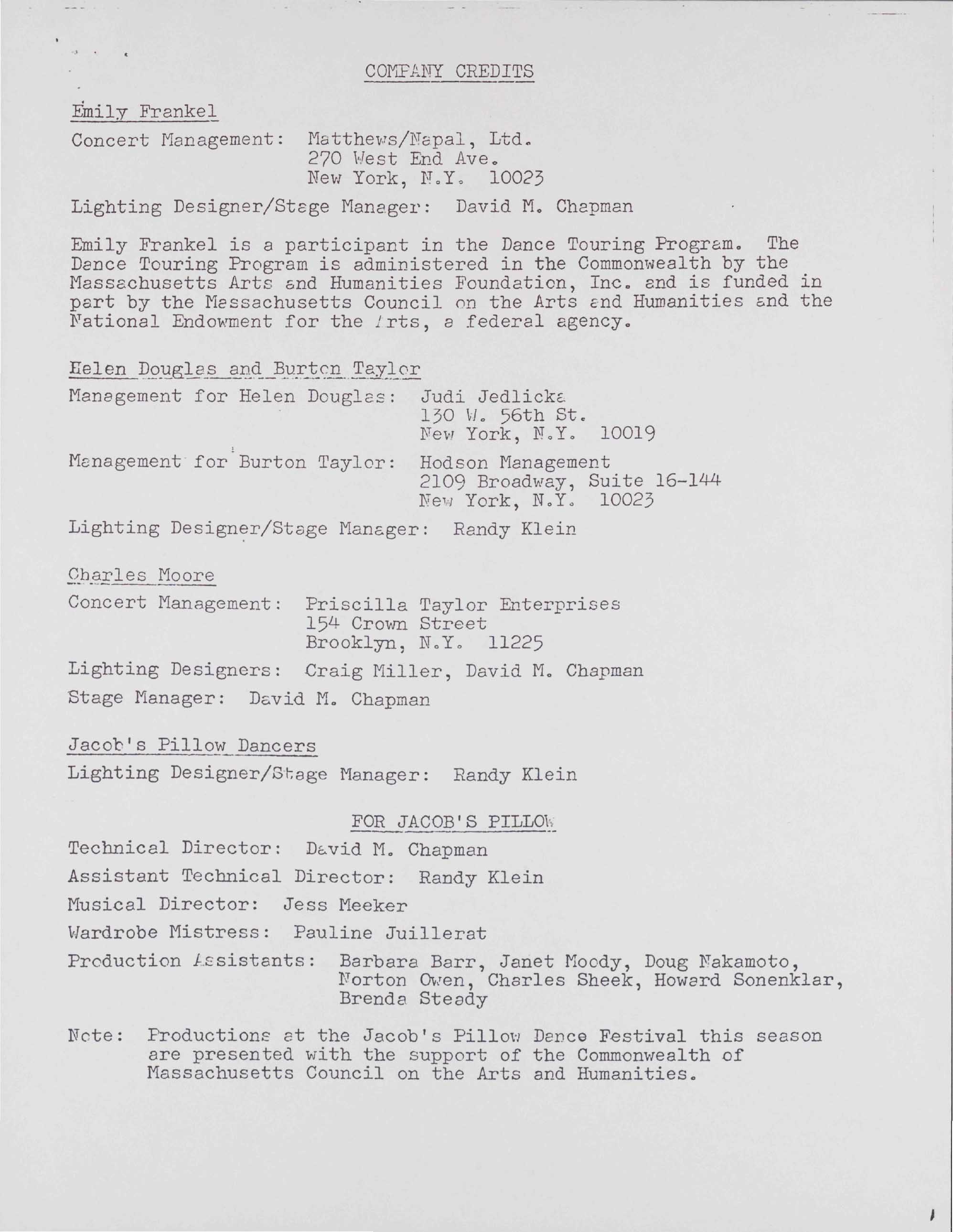

The printed program did not include any additional information about the four solos, but Courting Dance was very likely an excerpt from the earlier production of Kykunkor, where Bokari dances before a line of potential wives who reciprocate with their own dancing. What is more certain is that Dafora’s work was revived several decades later at the Pillow when Charles Moore and Dancers and Drums of Africa performed on August 15-19, 1978. Their program included Bundo or Maiden’s Dance and Jabawa, a festival dance, both excerpted from Kykunkor.Program, 46th Season, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, August 15-19, 1978.

In the continuing human chain of person-to-person transmittal of dance material, Charles Moore had studied and/or performed with Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Asadata Dafora.

Dafora and Sawyer’s opening section of the 1942 Pillow concert was followed by a second group of dances, American Dances Based on Primitive Motifs, in which Barton Mumaw performed Fetish, the first dance he had choreographed. He later described how it was based on poses he adapted from viewing African sculpture and how much he enjoyed personifying the “frenzy of incantations” of a Witch Doctor.Barton Mumaw and Jane Sherman, Barton Mumaw, Dancer (New York, NY: Dance Horizons Books, 1986), p. 260.Mumaw also performed two other self-choreographed solos, Dyak Spear Dance, personifying a warrior from Borneo, and The God of Lightening, based on an Aztec legend. The other dances in that section were Corn Grinding Song and Basket Dance from Shawn’s Hopi Indian dance drama, Feather of the Dawn, and Shawn also performed one of his signature solos Invocation to the Thunderbird. Arthur Mahoney and Thalia Mara closed out the program with a section titled Eighteenth Century Court Dances Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance—Season 1942. The opening season of the festival clearly followed the dance potpourri format that the Pillow would become noted for.

Dafora's Work Lives On

Dafora never returned to the Pillow after this first engagement, but he was often singled out in souvenir programs as a pioneering presence for black performers at the festival. In addition, one of his solos, Awassa Astrige, figured prominently in later performances. His elegantly sinuous choreography was first performed in July 1976 by Charles Moore accompanied by percussionist Ralph Dorsey.Program, 1976 Season—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—July 27-31.

The program note for the dance delineated its cultural importance: “Warriors imitate the powerful graceful movement of the king of birds. Living close to nature, they observe the movements of the ostrich, the largest and most powerful of the birds on the continent of Africa. This dance, from Sierra Leone, was introduced in the United States by Asadata Dafora.” Ibid. Two years later, Charles Moore reprised his performance of Awassa Astrige on a program that he shared with the Danny Grossman Dance Company. On that concert, he was joined by his wife Ella Thompson Moore and a company of ten dancers and four drummers.

The program, described as an “excerpt from a tribute to Asadata Dafora,” attributed all of the choreography to Dafora.Program, 46th Season, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, August 15-19, 1978. The dances included, as mentioned before, Bundo (Maiden’s Stick Dance) and Jabawa from Kykunkor. In addition, Spear Dance, which Randolph Sawyer had performed as a solo on the earlier concert, was performed by a group Ibid.

Nearly two decades later, Awassa Astrige was performed once more by a young Ronald K. Brown at the festival’s 65th Anniversary Opening Gala performance on June 21, 1997. Both Moore and Brown captured the distinctive beauty of the seminal artist’s dance aesthetic, as they honored his work.

However, Asadata Dafora’s continuing influence at Jacob’s Pillow has to do with more than the recurrent performance of his choreography. He was the first and foremost artist who brought the authentic cultural expressions of diverse African ethnic groups to American audiences. And his work, beginning in the 1930s, laid the foundation for many other artists and dance companies to pursue similar objectives. Among those that have performed at the Pillow are Babatunde Olatunji in the 1960s, Chuck Davis in the 1970s, Muntu Dance Theater, Sankofa Dance Theater, Bamidele Dancers and Drummers, and Batoto Yetu, in the 1990s, and Kuumba Dance and Drum in the 2000s. All of those groups may be thought of as forming a continuum that began with the pioneering artist from Sierra Leone.

The following biographical information included in a 1978 Jacob’s Pillow program touched on the multiple ways Dafora influenced generations of artists that followed him:

His uniquely authentic talents burst upon the New York entertainment scene in 1934 with the short run of his opera, Kykunkor subtitled “The Witch Woman”. Kykunkor not only shattered many myths concerning the potential of Black ethnic material as themes for concert dance, it proved Black dancers could be successful on the American concert stage. Kykunkor was the forerunner of all the national dance companies which introduced their culture to the American public through dance. It presented the native African with a real life humanity which had not been seen by America in the thirties.

The company of 25 called Shologa Oloba was made up of Africans and Afro-Americans whose dancing inspired fervent critical praise. Dafora’s success spurred other dancers to utilize this format and led to the widespread acceptance of Black dancers performing African heritage thematic materials as an art form.

The dance style of Asadata Dafora (Horton) was a carefully conceived theatrical presentation of folk forms. It combined precision and freedom of movement, differentiation of gesture, judicious use of face, arms, and feet in rhythmic patterns which heightened the meaning of dance.

Asadata Dafora (Horton) brought America a subtle forceful dance intelligence and a great humanistic wisdom that should not be forgotten.Ibid.

PUBLISHED August 2017