Early Influences in Haiti and the U.S.

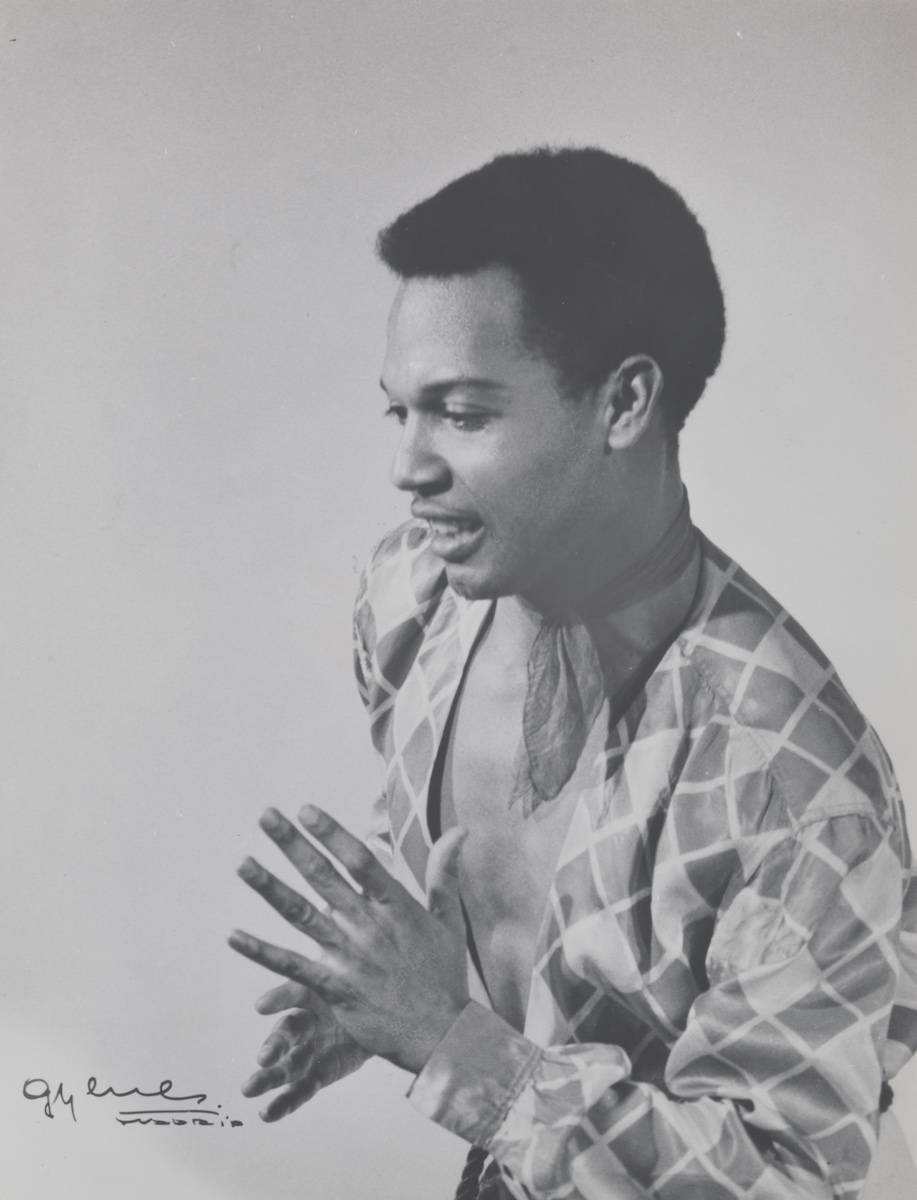

The strange spell of a Destiné performance, the visions he gives of the rhythmic richness, the proud and beautiful heritage of Haiti, is a testament of a great love for his land and his people. Destiné knows them as few others do, but he also is gifted with the artistry to bring the very magic of the mountain rites into the theatre."

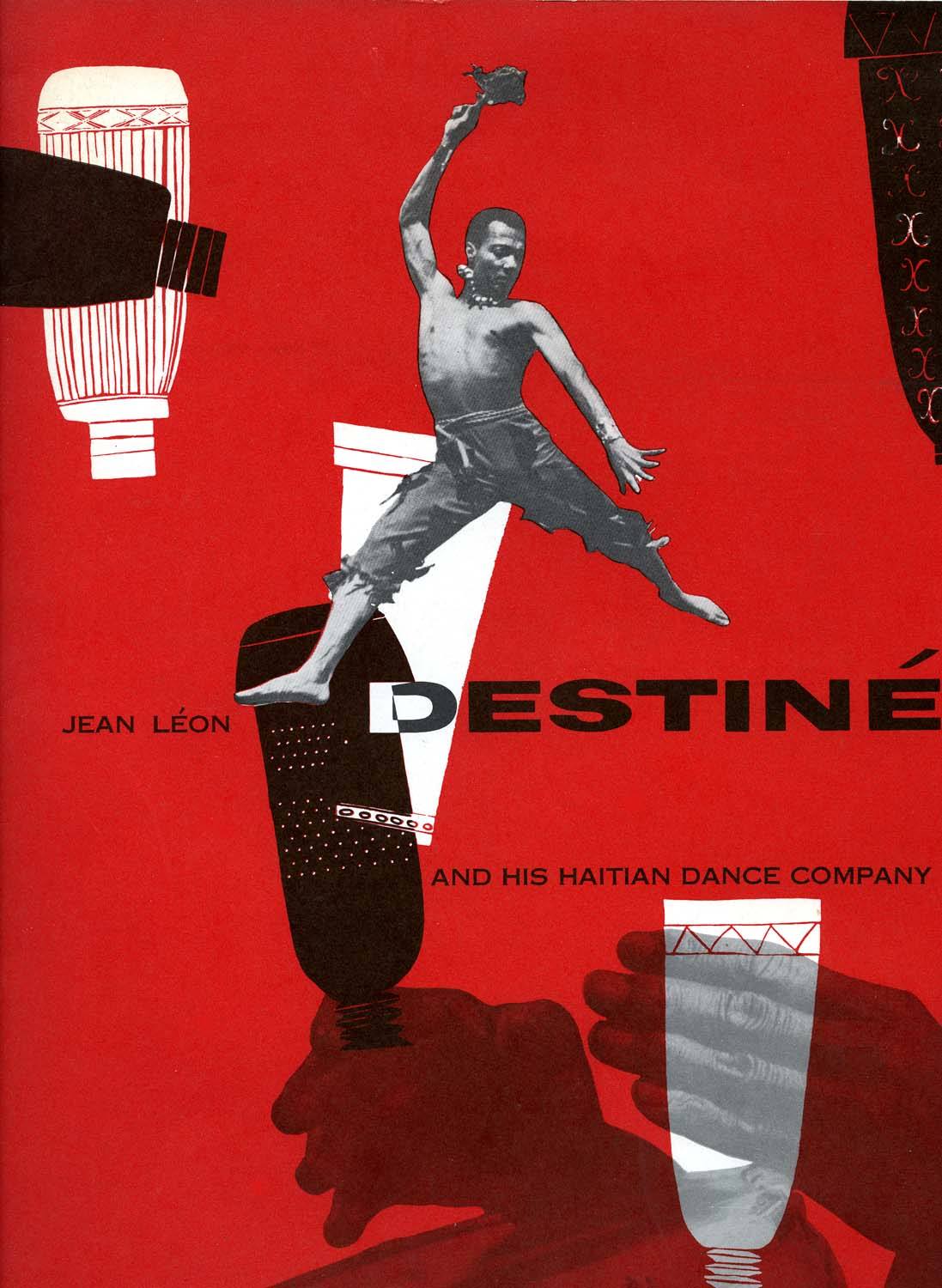

This passage from Jean Léon Destiné and His Haitian Dance Company(New York, NY: Dunetz and Lovett, n.d.), n.p., Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival Archives., an informative souvenir program/booklet, summarizes the significance of Destiné’s artistry during his early years as a dancer/choreographer on international stages. It also discloses an interesting parallel between his relationship to his theatrical material and that of another Pillow artist, Asadata Dafora, to his. The emphasis on proud, beautiful heritage, love of land and people, and bringing the magic of the material to the theater, all echoes the objectives of Dafora in his work. Moreover, these are all elements that can be found in the work of many of the African-diaspora artists discussed in these essays: they often had a sociocultural and sociopolitical objective in mind, as they pursued their aesthetic visions.

One can find another interesting parallel between Asadata Dafora and Jean Léon Destiné in their adventures of cultural discovery during their childhood. Both grew up in middle-class communities where the cultural values of the colonials were prized and those of the indigenous people were denigrated. In Destiné’s case, the voudun religious practices of Haitian peasants were frowned upon by black Haitians who had been acculturated to the ways of French colonials. In a 2004 interview at the Pillow, he reminds us of the severity of the proscriptions against participating in the “forbidden” rituals of the peasant population. He recounts that he was excommunicated from the Catholic Church because of his visits to voudun ceremonies.Norton Owen, Interview with Jean-Léon Destiné, July 7, 2004.

Fortunately for Destiné, there was an individual who encouraged his childhood interest in the folkloric practices of Haiti’s people. He became a student of Mrs. Lina Mathon Blanchet, a pioneer in the study of Haitian music and folkways. She invited him to join her newly formed troupe, and they traveled to Washington, D.C. to perform at Constitution Hall in 1941. Soon after that, he traveled to the U.S. for a second time, under the auspices of a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship that enabled him to study journalism and typesetting.Jean Léon Destiné and His Haitian Dance Company. However, his love of Haitian folk culture had made an indelible imprint on him by that time, and he began teaching, performing, and lecturing on Haitian dance in New York City.

As a child growing up in Haiti, Destiné had also been aware of Katherine Dunham’s work during her visit to the island in 1935. At that time, she became a recognized figure in Haitian intellectual and artistic circles. Later, when he arrived in New York as a scholarship student, he made it a point to seek her out, after seeing a poster for her Broadway show, Tropical Revue. He attended one of her performances and went backstage afterward to introduce himself; she ended up inviting him to her home and her school; and they established a lasting friendship.Norton Owen, Interview.

Dancing with Dunham, Establishing His Own Company, and Ballet Folklorique

After his two year scholarship and some initial New York City appearances, Destiné returned to Haiti, but his exciting performance abilities had been noticed by New York audiences and critics. Consequently, he received a cable from Katherine Dunham asking him to return to the U.S. to join her company.Jean Léon Destiné and His Haitian Dance Company. In November 1946, Dunham mounted one of her most successful revues, Bal Nègre, which opened at the Belasco Theatre. A high point of the production was Shango, with Jean-Léon Destiné performing the role of the boy possessed by a snake.Lynne Fauley Emery, Black Dance from 1619 to Today, second revised edition (Hightstown, NJ: Princeton Book Company, 1988), p. 257. As Dunham biographer Joyce Aschenbrenner points out, Bal Nègre attracted the attention of international producers, and it led to the company’s tour of Mexico and its first tour of Europe.Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2002), p. 132.

After the Dunham tours, Destiné continued to take advantage of the professional opportunities that opened up for him. Like Pearl Primus had before him, Destiné became associated with the artists/activists at the New Dance Group. Donald McKayle later remembered that Destiné was among the influential teachers he studied with when he entered the school as a scholarship student in 1947.Donald McKayle, Transcending Boundaries: My Dancing Life (London and New York, NY: Routledge, 2002), p. 26. In the international arena, the connections Destiné had made in Mexico led to his appearance in a short film, Bambu (1948); and in March of 1949 he performed in the New York City Opera’s world premiere of William Grant Still’s Troubled Island. During that same period, he formed his dance company, Destiné Afro-Haitian Dance Company.

Another indication of Destiné’s growing recognition as an artist whose star was on the rise was an invitation by the Haitian government to establish the first Troupe Folklorique Nationale. Plans were being made for the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the founding of Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital city; and they would result in a lavish Exposition Internationale in 1949. He was appointed as the artistic director of the project, and he would organize a large group of percussionists, singers, and dancers to perform an array of work that became the foundation for the company’s repertory.Jean Léon Destiné and His Haitian Dance Company. Author Allison E. Francis reminds us that the development of the Troupe Folklorique was, to a large extent, due to President Dumarsais Estimé’s interest in promoting Haitian cultural tourism.Allison E. Francis, “Serving the Spirit of the Dance: A Study of Jean-Léon Destiné, Lina Mathon Blanchet, and Haitian Folkloric Traditions, Journal of Haitian Studies, v. 15, no. 1 and 2 (Spring/Fall 2009), p. 309.

First Visit to the Pillow

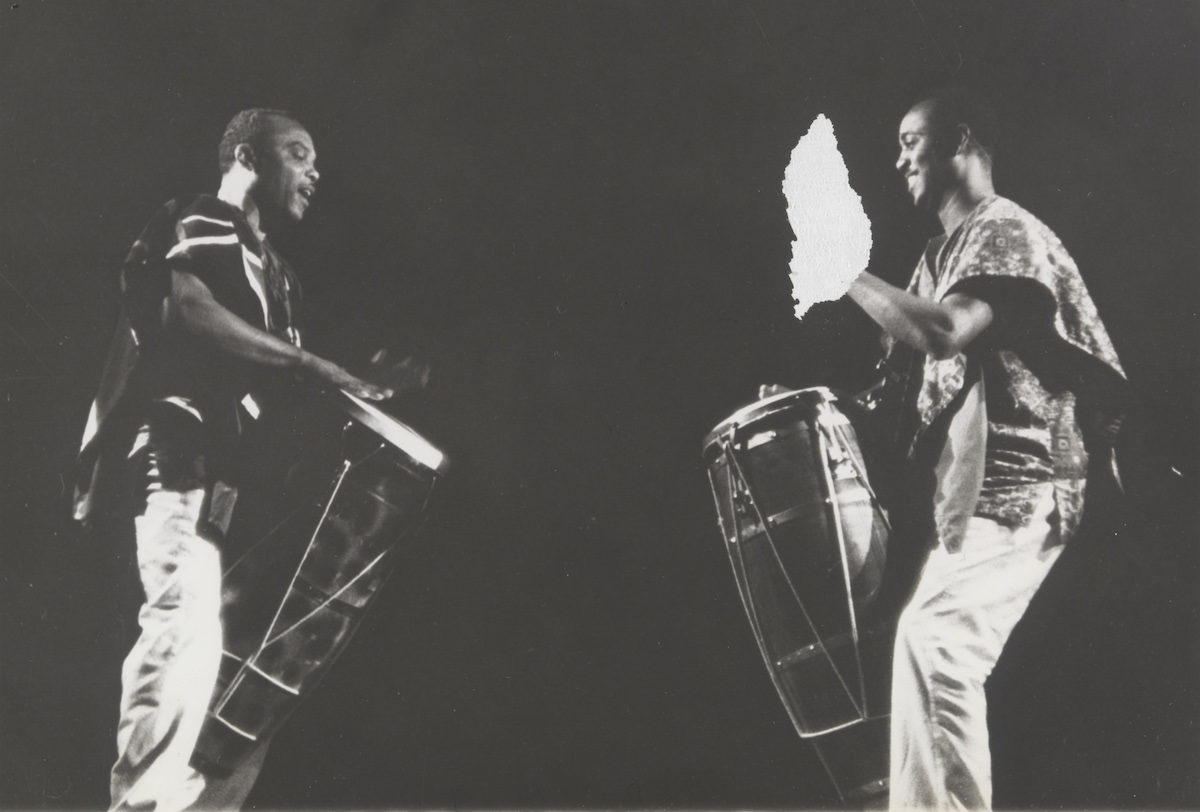

It was a long journey from the hills above Port-au-Prince, Haiti to the hills of Becket, Massachusetts, but Jean Léon Destiné seemed to have found smooth passage. He first appeared at the Pillow on August 26 and 27, 1949 along with his partner Jeanne Ramon and percussionist Alphonse Cimber, who had begun distinguishing himself in the early 1940s as an accompanist at the New Dance Group and as an accompanist for Pearl Primus’s first concerts in New York. Primus spoke of his importance when she said, “His hands played absolutely authentic African rhythms. It was as if he had never been away from the village cultures of the Republic of Benin—he claimed ancestry from that area, and the majority of Haitians have their roots in the Republic of Benin. He played the true rhythms of the ceremonies of Haiti, which are the rhythms of Africa.”Pearl Primus, quoted in “Alphonse Cimber, Drummer, is Dead,” New York Times, March 19, 1981.

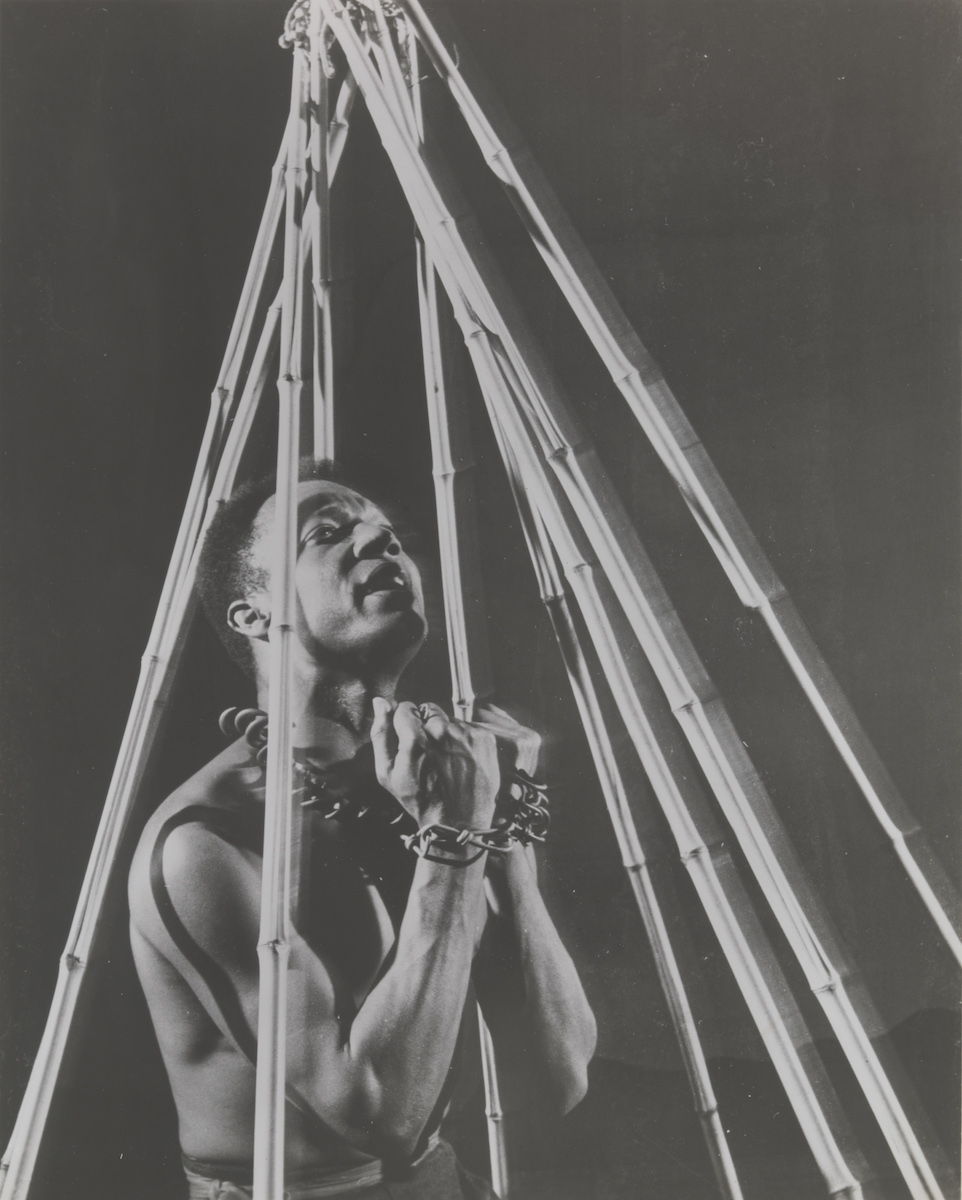

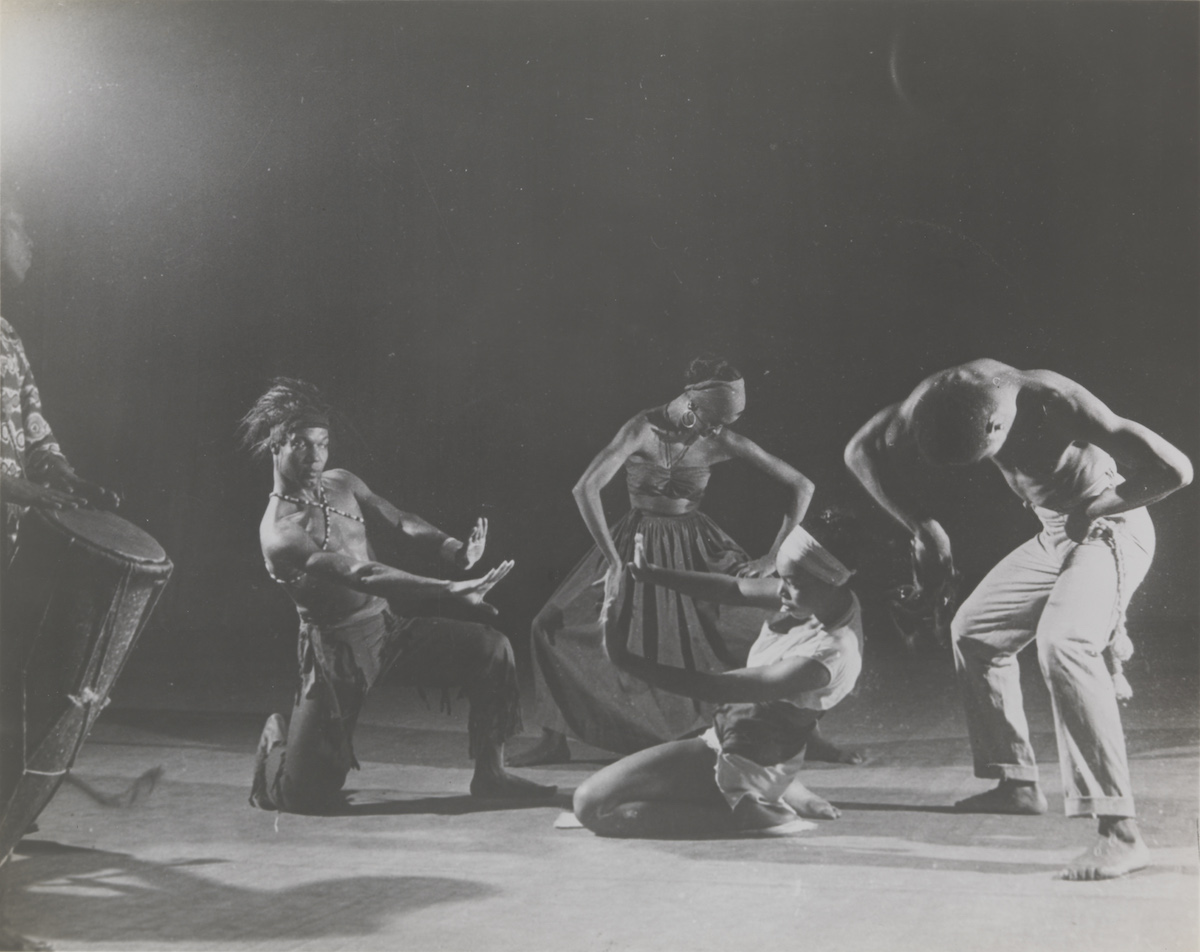

They opened the Pillow concert with Haitian Suite, which consisted of three dances and a drum solo for Cimber. Among the dances, Slave Dance was often singled out as one of Destiné’s outstanding solo works. Though there was no program note for the Pillow concert, a note from a longer souvenir program describes the dance as follows: “Beginning with an invocation to the gods in which the slave tells of his sorrows, this dance symbolizes the struggle for freedom by the slaves of Haiti.”Jean Léon Destiné and His Haitian Dance Company. The unique history of Haitian slaves’ successful revolution against their French masters was a story of heroic proportions that instilled pride in Destiné and his countrymen. Slave Dance reflected that history. Moreover, the souvenir program indicates that Destiné choreographed several other works that delved into that history. For example, a note for Le Serment des Ancêtres reads, “Let my body be possessed by the gods so they may give me the power to fight to the death for liberty.”Ibid.

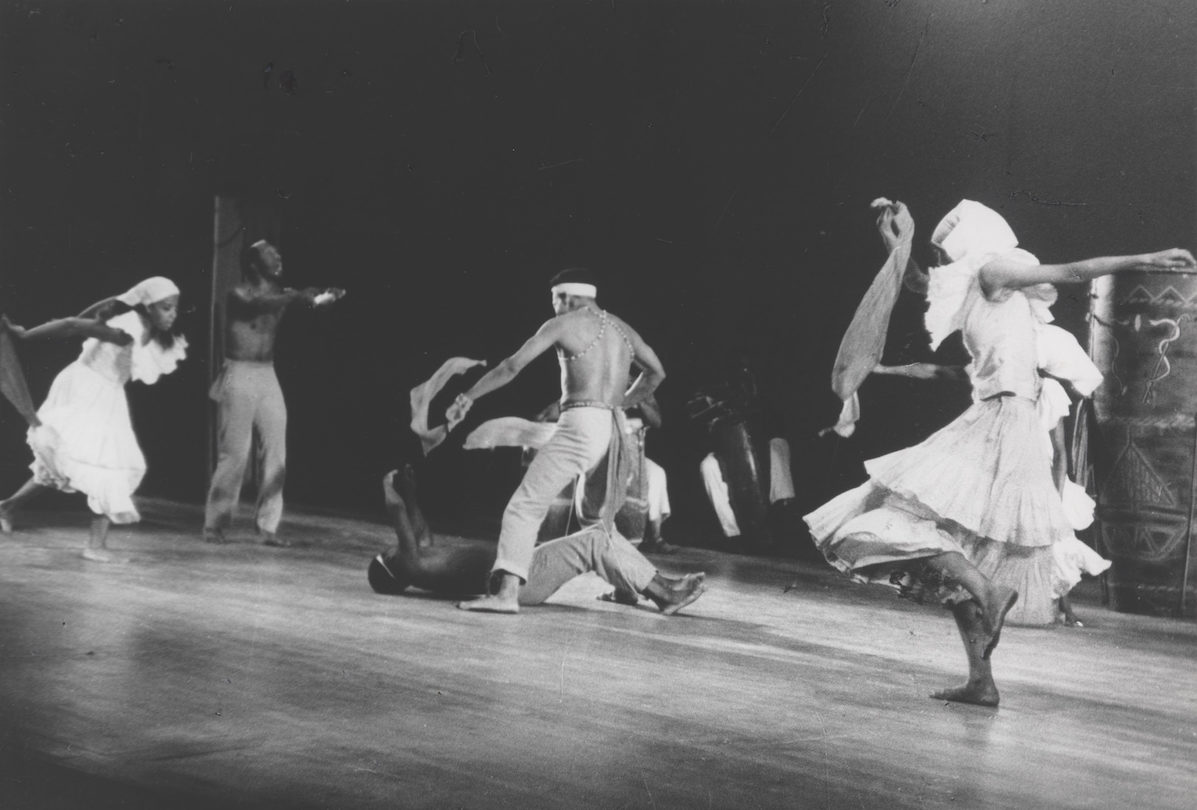

A later section of the 1949 Pillow concert explored lighter subject matter. Jeanne Ramon performed Play Dance and Destiné performed Carnival Dance; and after a dance choreographed by modern dancer Myra Kinch, Destiné and Ramon returned to the stage, closing the concert with Haitian Voodoo Dance. This work was based on adaptations of voudun ritual dances that were theatricalized for presentation on the proscenium stage.

Destiné had begun developing this approach during his earlier visits to the U.S., and it was an approach that other artists—most noteworthy, Katherine Dunham—had begun to explore before him. Dunham’s visit to Haiti and other Caribbean islands in 1935 had played a key role in the establishment of her aesthetic trajectory that brought the music, dance, and folklore of the African diaspora to Western audiences. And Destiné later stated that she was also instrumental in developing an appreciation for those folkloric cultural elements among Haiti’s intelligentsia.Norton Owen, Interview with Jean Léon Destiné. She had immersed herself in the voudun religion to the extent that she took part in the rigorous initiation rites recounted in her book Island Possessed.

Performing “Possession”

In her evolving career that blended dance performance, anthropological research, sociological insight, and theater, Dunham gravitated toward the danced religions of the African diaspora as an important element in her art-making. She was fascinated by the fact that these were forms of worship that embraced the dancing human body as the pivotal element that bridged the distance between sacred realms and daily existence. She, Destiné, and others—like Asadata Dafora, Pearl Primus, Maya Deren, and Lavinia Williams—knew that religions such as voudun centered on the phenomenon of divine spirits entering into the bodies of worshipers and manifesting their presence through dance. The resulting state of spirit possession was as mesmerizing to watch as it was transformative to experience. No wonder critics were often amazed when performances based on these ritual dances were brought to the stage.

An altered state of consciousness, similar to that of spirit possession, can be achieved in a number of ways. It can be drug-induced, brought on by techniques of hypnosis, or it can be instigated in physiological ways. For example, Dunham believed that dances such as Les Zepaules—that featured rapid, shuddering movement of the shoulders—affected the body’s chemistry in such a way that it contributed to spirit possession. Movement vocabularies that featured repetitive contractions and undulations were common in the Haitian dances she set out to explore in the 1930s. These were the same dances that Destiné began learning at an early age.

In a 1981 study of Katherine Dunham’s career, author Joyce Aschenbrenner discusses the artist’s insight into the effect of different dance movements on the human body in Haitian dance:

[F]unction is indicated by the emphasis on various parts of the body and the type of movement. For example, in the Petro dance in Haiti, which accompanies a destructive, antisocial cult, the body movement involves opposition, projecting a hostile, “frenzied” feeling tone, preparing the participants for aggressive action. On the other hand, the Yonvalou often representing the benevolent Rada Dahomey god, Damballa, displays a fluidity, a soothing motion—an undulating movement signaling acceptance, prayer, ecstasy. The Zepaules, also a Rada Dahomey dance—exhibiting a contraction and expansion of the shoulders in jerking movement—induces a kind of self-hypnotism, and the accompanying rapid breathing generates excitement. The Congo Paillet, in which a movement of the haunches is involved, is sexually stimulating, as are the dances with hip and stomach rotation. For all of these dances, release—the externalization of energy and emotions—serves a critical function.Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Reflections on the Social and Political Context of Afro-American Dance, CORD, Inc., 1980 Dance Research Annual XII, 1981, p. 63.

Accompanied by incessant drumming that had the communicative power and intricacy of a spoken language, the dance movement itself enabled possessed dancers to become one with the many spirits of the voudun pantheon.

I believe that the dance material Dunham, Destiné, and other artists drew upon was successfully transposed into Western theatrical art for a number of reasons. As described above, their movement sources were inherently dynamic, dramatic, and transformative. Moreover, different types of dance—whether ritual, social, or theatrical—share some of the same elements (rapid breathing, release, externalization of energy and emotions) that Dunham spoke of. To varying extents, these are commonalities that can propel someone enjoying swing dance or someone performing a modern dance toward the liminal boarders of altered states of consciousness. However, because of their culturally specific characteristics, dances such as those of Haitian voudun were especially capable of slipping from the transformative arena of ritual to the transformative arena of theatrical art.

Dancing Gods and Shawn’s Travels to Haiti

Within the context of this discussion, it should also be noted that Ted Shawn and his artistic partner of many years, Ruth St. Denis, were especially interested in world cultures where dance was closely allied with religious beliefs and ecstatic spiritual expression. Over their decades of performing, they choreographed works such as Kuan Yin, based on the Chinese Goddess of Mercy, and The Cosmic Dance of Siva, that reflected on the Hindu Lord of the Dance. In these, they not only underscored their interest in the relationship between dance and the divine, but they also heightened the purpose of their art-making by wrapping themselves in a mantle of spirituality. As author Jane Sherman said about Ruth St. Denis, “She claimed that she had but one great message: the expression of God through Dance.”Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1979) p. 45.

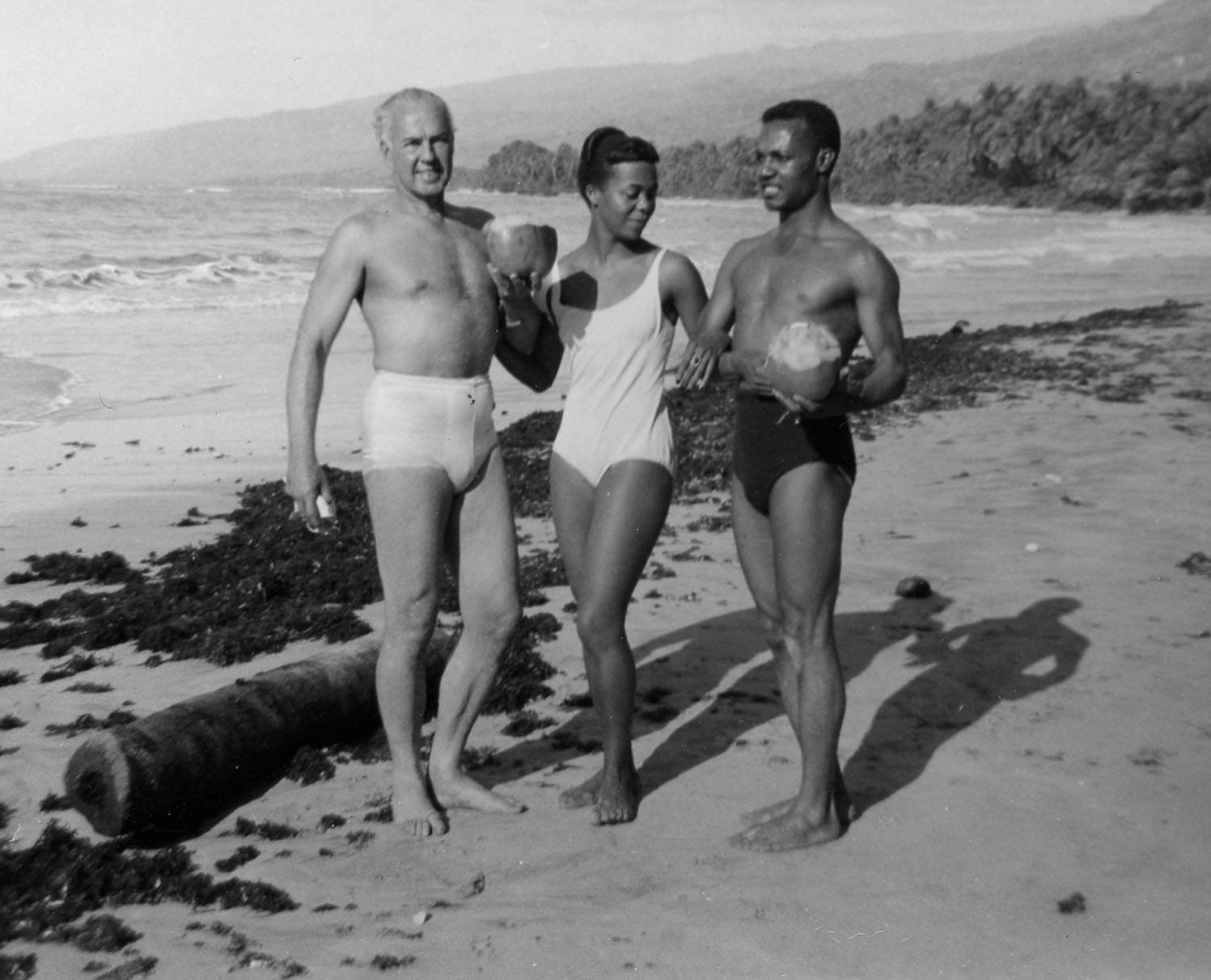

Their company, Denishawn, toured the world, taking their cultural interpretations to diverse audiences, and it also allowed them to observe the ritual dances of other cultures. After meeting Destiné and establishing a professional relationship and friendship with the artist, Shawn developed a growing interest in Haitian ritual dance; so when he learned of Destiné’s plan to return home to form the Ballet Folklorique, he made arrangements to go to Haiti during the Christmas holidays of 1949.

As Shawn later recounted in a Dance Magazine article titled “Black Christmas,” he and his two traveling companions, John Christian and Bertha Damon, attended several voudun ceremonies while they were in Haiti, and they witnessed worshippers become possessed. In addition, they were able to attend performances of Ballet Folklorique at the Theatre de la Verdue.Ted Shawn, “Black Christmas,” Dance Magazine, v. XXIV, no. 5, May, 1950, p. 28. Shawn commented on the opportunity he had to compare the “raw material” of the ceremonies to the performances he saw at the theater. He spoke of how impressed he was that Destiné was able to get his forty dancers, who were untrained as theater artists, to perform so commendably. “Entrances and exits were perfectly timed, group patterns were never faulty, and the performers all maintained an air of authority and confidence almost never seen in dancers who have not had long professional experience before audiences.”Ibid., p. 49. Since Shawn witnessed several of the company’s performances, he could see that even the possession sequences, with all of their ecstatic verisimilitude, were choreographed sections that could be repeated with exactitude. Overall, he felt that Destiné had done an extraordinarily fine job of transposing the danced rituals from their authentic setting to the concert stage. He concluded, “[T]here is so much for a student of the dance to learn from a people who more than any other people in the world today express their religion in an infinite and inexhaustible variety of dance forms.”Ibid., p. 35.

Destiné’s Lasting Contributions to Cultural Life at the Pillow

Destiné returned to Jacob’s Pillow for the two following summers, in 1950 and 1951, reprising Slave Dance and presenting new dances such as Market Dance for Jeanne Ramon, Spider Dance and L’Appel au Tambour for himself, and several duets that reflected the influence of French set dances on the Haitian people. In the latter category, Ramon and Destiné, costumed in eighteenth-century, French-inspired costumes, performed Martinique and Creole Fantaisie.Programs, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival–Ninth Season–1950 and Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival–Tenth Season–1951.

Shawn recounted an interesting event—also during the summer of 1951— that reflected how Haitian cultural practices occasionally found a place in the life of the Pillow. He was constantly undertaking projects that would improve the festival’s amenities; and that season, workers were drilling a new well so that there would be more water available for the bathrooms and other facilities:

On our first bill were Jean Léon Destiné, Jeanne Ramon and Alphonse Cimber, the great Haitian dancers and drummer. Destiné had brought me a beautiful voodoo drum, carved and painted especially for me by one of the most important voodoo priests of Haiti. Before a voodoo drum can be used, it must be baptized in a special ceremony. So I had the well drillers draw up the very first bucket full of water from the new well, and in the intermission of the first matinee, Destiné, Cimber and I held the Baptismal ceremony in his dressing room, and I said a prayer of thanks to Simbie de l’eau, Haitian Goddess of water, for having given us water.Ted Shawn, “MY SEVENTH ANNUAL NEWS LETTER IN LIEU OF THE CHRISTMAS GREETINGS I DID NOT SEND YOU, AND TO THANK YOU FOR THE ONE YOU DID SEND ME–1951,” p. 2, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival Archives. This is a collection of Shawn’s accounts of important events from the previous year. His letters/reports were usually very detailed, lengthy, and interesting in terms of the daily happenings in his life and at the festival.

That Destiné was one of Shawn’s favorites to invite to the Pillow is attested to by the sheer number of appearances the Haitian artist made over the years. He and his company visited the festival ten times from 1949 to 2004, a span of more than fifty years. Early on, Shawn also wrote a letter that included statements about his admiration of Destiné. This occurred when Shawn responded to a complaint by Talley Beatty about a purportedly racist incident that happened in connection with the festival housing where he and his company were staying. Shawn singled out his positive relationship with Destiné as part of his counter argument. As he put it, “We all feel that Destiné is not only a fine artist, but a very fine and honorable gentleman, who reflects great credit upon his race, and has been a most constructive influence towards healing any misunderstanding, wherever they may exist.”Ted Shawn, Letter to Talley Beatty, July 21, 1952. In his own turn, Destiné later said that he always felt comfortable at Jacob’s Pillow, though he had encountered racial incidents during some of his other performance experiences.

Destiné’s many visits to the Pillow enabled him to make outstanding contributions to the festival’s artistic community. His performances brought the unique beauty and potency of Haitian dance to the Berkshires; and, as Shawn pointed out in his Dance Magazine article, Destiné presented the dances of voudun, but there were also secular dances—the flirtatious dances of Mardi Gras, work dances of the peasants, and social dances of sophisticated grace.Ted Shawn, “Black Christmas.” As the first person of color on the faculty at the Pillow, Destiné was able to share these rich cultural elements with his students for more than five decades. His presence at the festival reflected the generosity of his spirit, the clarity of his artistic vision, and the enduring significance of his people’s dance.

PUBLISHED July 2017