The Early Stages

When Pearl Primus performed at Jacob’s Pillow for the first time on August 16, 1947, she was in the early stages of establishing her career as an important theatrical concert dancer on the American contemporary dance scene. One of her strongest influences during her early search for aesthetic direction was her intense interest in her African-diaspora heritage; this became a source of artistic inspiration that she would draw on throughout her entire career.

When she was three years old, her family had moved from the island of Trinidad and resettled in New York City, but her relatives kept the memories of their West Indian roots and their African lineage alive for her, distilling them into stories that transmitted a sense of cultural and historical heritage to the young girl. Her familial ties laid the foundation for the art she would later create.

She began her formal study of dance in 1941 at the New Dance Group, where she studied with Jane Dudley, Sophie Maslow, and William Bales. Her early years with the dance collective not only grounded her in contemporary dance practices, but they exposed her to the unique brand of artistic activism that the organization had embraced when it was established in 1932. The New Dance Group’s motto—“Dance is a weapon”—encapsulated the idea that dance performance should be much more than “art-for-art’s-sake.” Dance artists should be acutely aware of the political and social realities of their time, and they should use that awareness to create work that had an impact on the consciousness of the individuals who saw it. The New Dance Group Gala Concert: An historic retrospective of the New Dance Group presentations, 1930’s – 1970’s (New York, NY: The American Dance Guild, 1993) pp. 6-9.

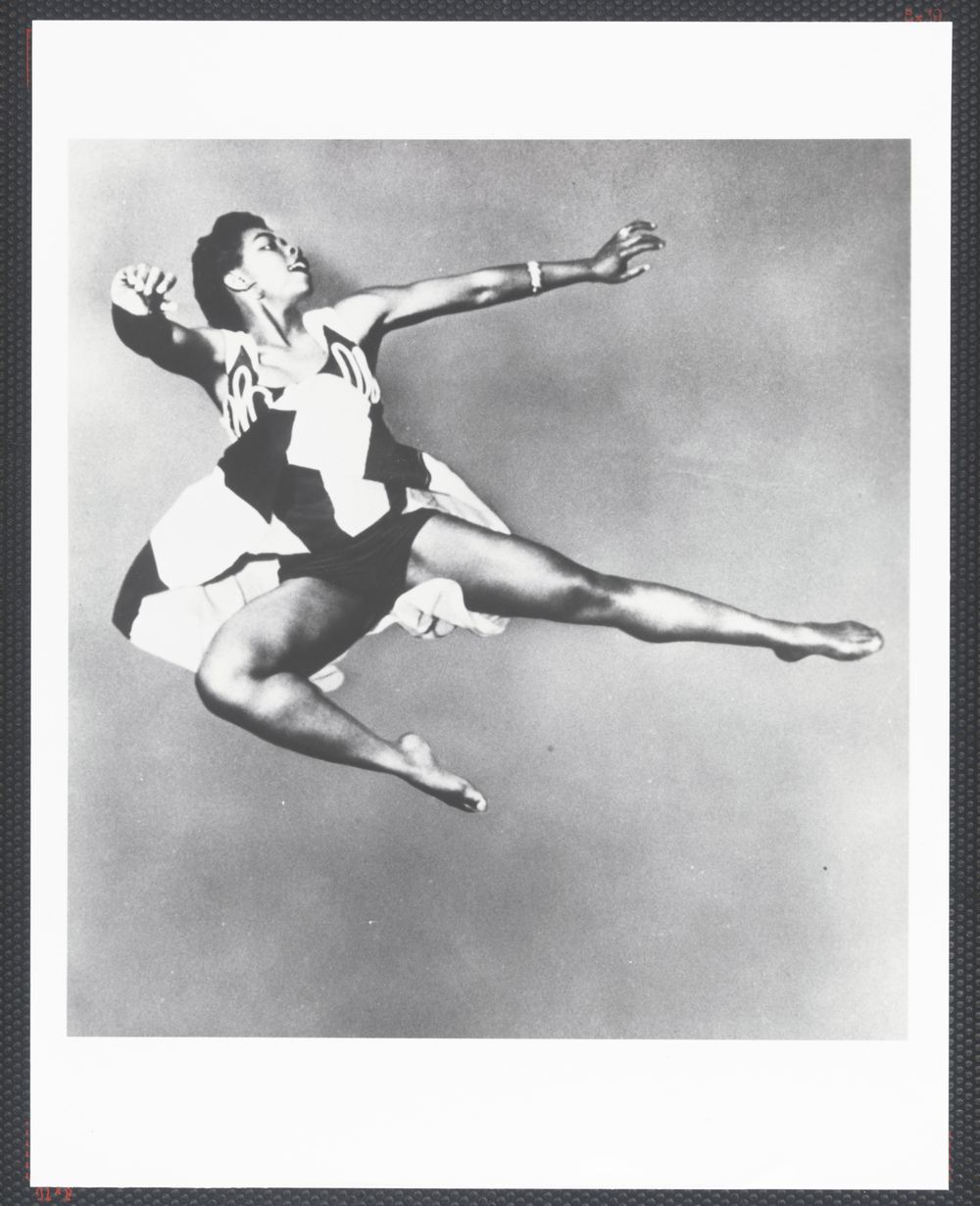

Soon after she began studying at the New Dance Group, Primus started to choreograph her own works and distinguish herself as a compelling solo performer with a distinctively visceral approach to movement that was full of explosive energy and emotional intensity.

On February 14, 1943, her first major performance took place at the Ninety-Second Street YM-YWHA in New York City, where she appeared in a joint concert, Five Dancers, along with four other emerging young artists Nona Schurman, Iris Mabry, Julia Levien, and Gertrude Prokosch. New York Times dance critic John Martin—who would become a devoted champion of the young dancer over the years—singled Primus out as a “remarkably gifted artist;” and he went on to comment positively on her technique, her stunning vitality, and her command of the stage.John Martin, “The Dance: Five Artists,” New York Times, February 21, 1943, Sec. II, p. 5 One of the dances Primus performed on the program was Hard Time Blues, a work that she would reprise at Jacob’s Pillow four years later. She would also share that program at the Pillow with Iris Mabry.

Discovering Cultural Origins

She developed a growing awareness that people of different cultures performed dances that were deeply rooted in many aspects of their lives.Primus’s early experiences as a student of dance and as a young black woman with an evolving political and social consciousness resulted in her having several intertwined objectives. She was determined to fully explore the available resources for formal dance training by studying with major contemporary artists of the time such as Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham. She developed a growing awareness that people of different cultures performed dances that were deeply rooted in many aspects of their lives. Moreover, she developed an overarching interest in the cultural connections between dance and the lives of the descendants of African slaves who had been taken to widespread parts of the world. For example, her first performance at Jacob’s Pillow was comprised of repertory works that drew upon the cultures of Africa, the West Indies, and the southern region of the United States.

Hard Time Blues was a dance that focused on the plight of southern sharecroppers. Prior to her debut at Jacob’s Pillow, Primus spent the summer of 1944 traveling through several southern states, observing and participating in the lives of impoverished black farm workers and attending their church services and social gatherings. Her travels were clearly connected to her overarching interests mentioned above, and they also informed the type of protest dances that grew out of the New Dance Group’s objectives: “The New Dance Group aimed to make dance a viable weapon for the struggles of the working class. They were artistic innovators against poverty, fascism, hunger, racism and the manifold injustices of their time.” The New Dance Group Gala Concert, p. 6.

Margaret Lloyd, the dance critic for the Christian Science Monitor, described Hard Time Blues in words that underscored the airborne athleticism Primus became renowned for, “Pearl takes a running jump, lands in an upper corner and sits there, unconcernedly paddling the air with her legs. She does it repeatedly, from one side of the stage, then the other, apparently unaware of the involuntary gasps from the audience… The dance is a protest against sharecropping. For me it was exultant with the mastery over the law of gravitation.” Margaret Lloyd, Borzoi Book of Modern Dance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Books, 1949), p. 271..

Another work on her 1947 Jacob’s Pillow program was also rooted in black southern culture. She presented Three Spirituals—“Motherless Child,” “Goin’ to tell God all my Trouble,” and “In the Great Gettin’-up Mornin’. Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival: Opera and Opera Ballet, Season 1947.By the 1940s, the extensive canon of Negro spirituals or “sorrow songs” that stemmed from American slave culture had become a recurrent source of artistic inspiration for contemporary dance artists. Beginning in 1928 and continuing over the next two decades, European-American artist Helen Tamiris explored the African-American folk music in several dances that comprised her suite, Negro Spirituals. Ted Shawn and his Men dancers presented their Negro Spirituals on tour and in New York City performances during the 1930s; a program dated August 18, 1934 indicates that Ted Shawn and his company performed Three Negro Spirituals at a benefit concert for the Long Ridge Methodist Episcopal Church in Danbury, Connecticut. Edna Guy, one of the earliest African-American dancers to perform danced spirituals, was also the first black student to be accepted at the Denishawn School in New York City.

Primus also included dances from Africa and the West Indies, when she appeared at the Pillow for the first time. Her interest in world cultures had led her to enroll in the Anthropology Department at Columbia University in 1945. She had not yet undertaken fieldwork on the continent of Africa, but based on information she could gather from books, photographs, and films, and on her consultations with native African students in New York City, she had begun to explore the dance language of African cultures. At the Pillow, she performed Dance of Beauty, with a program note stating, “In the hills of the Belgian Congo lives a tribe of seven foot people. Their dignity and beauty bespeak an elegant past.” Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Season 1947.Another program note for Dance of Strength stated, “The dancer beats his muscles to show power. Common in the Sierra Leone region of Africa.” Ibid.Rounding out that section of the program were Santos, a dance of possession from Cuba, and Shouters of Sobo.

Her interest in world cultures had led her to enroll in the Anthropology Department at Columbia University in 1945.Primus’s 1947 concert followed a format that Ted Shawn adopted at the time of his festival’s opening in 1943. Author Norton Owen notes that Shawn credited the practice of putting diverse dance offerings on a single concert to Mary Washington Ball. In 1940, at a point when Shawn was thinking of selling the property because of financial difficulties, Ball, a dance teacher from New York, leased the Pillow with an option to buy, and she produced “The Berkshire Hills Dance Festival,” showcasing ballet, modern, Oriental, and Spanish dance. Norton Owen, A Certain Place: The Jacob’s Pillow Story (Lee, MA: Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 2002), p. 11.Everything in Shawn’s background indicates that he would have enthusiastically followed this type of programming that ranged far and wide among the dance expressions of the world. The concert Primus appeared on included ballet—excerpts from Les Sylphides and Aurora’s Wedding—and four modern dances by Iris Mabry.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Season 1947.

Each time Pearl Primus appeared at Jacob’s Pillow, her performances were informed by actual fieldwork she had just completed. The first time, it had been her travels in the South. The second time—July 21 and 22, 1950—she had returned from Africa several months earlier.

Her research in Africa was funded by the Rosenwald Foundation, the same philanthropic organization that had sponsored a similar research trip to the Caribbean for Katherine Dunham in 1935. Primus’s extensive travels took her to nine different countries, where she was able to observe, study, and learn an encyclopedic array of dances with their deep cultural connections to the people.

Dance critic Walter Terry wrote an article discussing the time she spent interacting with people from more than thirty different tribal groups, and he described the knowledge she had gained from her research. She had learned how the dance expressions of the people were connected to a complex system of religious beliefs, social practices, and secular concerns, ranging from dances that invoked spirits to intervene on behalf of a community’s well-being to dances for aristocrats that distinguished their elevated social class. Walter Terry, “Dance World: Hunting Jungle Rhythm,” New York Herald Tribune, January 15, 1950, Sec. 5, p.3.

For the balance of her career—in her interviews and through her lecture-demonstrations and performances—she would stress the complex and interrelated functions of dance in the different cultures of Africa and its diaspora.

Excerpts From An African Journey

Her 1950 performance included previously seen works such as Santos and Spirituals, which varied slightly from her earlier program. Two of the spirituals were the same, but “‘Tis Me, ‘Tis Me, Oh, Lord” replaced “Motherless Child.”

Her new works were performed in a section of the program titled Excerpts from an African Journey. Included were Dance of the Fanti Fishermen, from Nigeria and Benis Women’s War Dance, and the last dance of that section was Fanga, Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Ninth Season, 1950.a Liberian dance of welcome that became an iconic piece in her repertoire. Biographers Peggy and Murray Schwartz point out how Fanga became a dance that was often the central focus in her lecturing and teaching after she returned from Africa.Peggy Schwartz and Murray Schwartz, The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 88-89.

The dance was also appropriated and transformed by a number of artists, recycled in different versions, and it found its way into professional dance companies and community dance groups around the world as a symbolic dance expression of African cultures. In their book, the Schwartz’s include a program note from a 1951 performance of Fanga in New York City. The note seems to succinctly capture Primus’s deep affection for and attachment to the dance: “I welcome you. My hands bear no weapons. My heart brings love for you. I stretch my arms to the earth and to the sky for I alone am not strong enough to greet you.” Ibid., p. 264.

As with other programs at the Pillow, the July 1950 concert was composed of artists with different stylistic and aesthetic approaches to dance. Primus was joined by Lillian Moore, who performed her own choreography and that of Agnes de Mille; Lucas Hoving and Betty Jones, performed their own work; and José Limón, Letitia Ide, and Ellen Love, performed Doris Humphrey’s Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias, a work based on the poetry of Federico Garcia Lorca. Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

Touring Internationally

Primus was at a point in her career where the momentum of her early years continued to develop, and she widened her horizons as a performer and a choreographer. Her first international tour took her to England in January 1952; from there, she traveled on to Liberia for the second time; and then she continued to Israel and to France. When she returned to the United States, she continued her efforts to maintain a company and a school that would forward her artistic vision. One of the primary factors that enabled her to shore up these aspects of her professional life was connected to her personal life.

In 1952, she led a group of female students on a research trip to her home island of Trinidad, where she met Percival Borde, a talented dancer and drummer who was performing with Beryl McBurnie’s Little Caribe Theatre. Primus had studied and performed with McBurnie when the older woman was in New York City during the early 1940s, so Primus’s research trip gave them an opportunity to reconnect. It also laid the foundation for her relationship with Borde, who would follow her back to New York, marry her, and become her partner in all aspects of her life.

Over the decades, Primus’s involvement with Jacob’s Pillow continued, but instead of focusing on her own performance abilities that had stunned audiences during earlier years, she turned her attention to others. In 1965, for example, she choreographed four out of the five works performed by Percival Borde and Company—Beaded Mask, Earth Magician, War Dance, and Impinyuza. She often recounted how she had been taught Impinyuza during her travels in Africa, after being “declared a man” by the royal monarch of the Watusi people. She later taught it to her husband, “who performed it as his signature piece until his death, in 1990,” and it was also performed by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1990. The Dance Claimed Me, p. 98.

The Later Years

During later years, there were other projects inspired by her choreography, such as a reimagining of Bushasche, War Dance, A Dance for Peace, a work from her 1950s repertoire. In 1984, Primus taught the dance to students of the Five College Dance Department, where Peggy Schwartz was the director. Schwartz, in turn, kept the spirit of the work alive by having Jawole Willa Jo Zollar reimagine it for another group of college students more than a decade later. That version, Bushache: Waking with Pearl, was performed on the Inside/Out Stage on June 28, 2002 in conjunction with the program A Tribute to Pearl Primus.

Zollar’s project involving Primus’s work revealed a number of remarkable connections between the artists. Both drew on types of movement that are often found in the dances of Africa and its diaspora. These include grounded movement that privileges deeply bent knees, rhythmically percussive movement driven by highly propulsive energy, and the isolated articulation of different body parts, to name a few. For the Bushasche project, Zollar did have videos of the version that Primus taught to the Five College students in 1984; so, of course, she would have been influenced by it. Moreover, to honor the original work was part of her objective. But, here, it is also important to note the obvious—that the younger artist had explored those types of movement elements well before the Primus project took place. She had recognized that they were a part of her cultural heritage, and she made them the centerpiece of her dance aesthetic. No doubt, Schwartz chose Zollar for the Primus project because she recognized their similar histories of cultural discovery through dance.

Another connection between the two artists was their unswerving commitment to use their creative endeavors in the name of social and political change. As we have seen, Primus began following that path in the early 1940s, at the very beginning of her career. Similarly, Zollar gravitated toward the role of artist/activist early in her career. She was a fledgling artist during the 1960s, when the Black Arts Movement was coming into its own in America, with its message of using art to increase self-representation, self-determination, and empowerment among people of color. Again, we come to one of the recurrent themes of these essays: It was important—during the different decades of the 20th and 21st century—for black artists to create work that served a number of purposes that went far beyond the creation of art for the sheer pleasure of aesthetic contemplation.

Zollar’s first project involving the legacy of Pearl Primus inspired her to continue in that direction, and she choreographed a lengthier work using the same title, Walking with Pearl. It toured extensively, though it was not performed at the Pillow. However, Primus’s original works continued to be performed at the festival. On July 7, 2011 University Dancers with Something Positive, Inc. presented several of her works on the Inside/Out Stage. The program consisted of an excerpt from Statement, and Negro Speaks of Rivers, Strange Fruit, and Hard Time Blues. All of the works except Statement had been restaged two decades earlier as a part of an American Dance Festival project, The Black Tradition in Modern Dance, that had been initiated to preserve important works by black choreographers. For that project, Primus taught the solos to Kim Bears, a young dancer from the Philadelphia Dance Company (Philadanco), and it was Bears who restaged them for the 2011 performance at the Pillow.

Like the stories of so many of the artists discussed in these essays, Pearl Primus’s story recounts the many paths she took on her way to accomplish her artistic vision, a vision that included her love of performing, her commitment to social and political change, and her desire to pass her knowledge and her artistry on to later generations. For her, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival was a place where all of those paths and visions intersected. I find it remarkable that Ted Shawn’s festival in the Berkshires became a sort of crossroads where so many artists of color could engage in what Peggy Schwartz described as “a synchrony of aesthetic passions.”Peggy Schwartz introducing A Tribute to Pearl Primus, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, June 28, 2002

PUBLISHED May 2017