Thoughts on Archival Research at Jacob’s Pillow

In an earlier essay for Dance Interactive, I spoke of the common aesthetic elements I often find as I look at the choreography of African-American concert dance artists. Many of those elements are rooted in the movement languages of diverse African-diaspora cultures. In previous writings, I have also mentioned my interest in the aesthetic differences that distinguish an individual artist as a unique creative spirit whose work should not be relegated to an all-encompassing category that essentializes the elements he or she uses in their choreography. In this essay, as I look at the work Ronald K. Brown has brought to Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival over the past two decades, I find myself using the same approach, one that acknowledges the family similarities that often exist between African-American, African, and West Indian dance artists, but one that also celebrates the singularly innovative contributions each artist makes to the world of concert dance.

The Archives at Jacob’s Pillow have proven to be an ideal place for me to undertake the type of work described above, because they provide valuable material for the examination of the aesthetic similarities and differences that can be found in the work of black dancers and choreographers of different periods and different places. From the time that Asadata Dafora first performed at the Ted Shawn Theatre in 1942 to the recent visits of Ronald K. Brown, the festival has continued to develop an archival collection that is remarkable for its depth and breadth.

As I have worked in the Archives, I have noticed how advancing technology and evolving archival practices have incrementally affected the quality and the quantity of the research material that spans the decades. The grainy, black-and-white films of earlier performances have been supplanted by today’s richly-hued digital recordings shot from several different angles; documentation of other festival events—such as pre- and post-performance talks and interviews with artists—provide increased insight into the choreographers’ creative processes. The same is true of printed programs which have expanded to include informative essays by resident dance scholars. The result has been the establishment of a treasure trove of research material that has enabled me to trace the careers of significant dancers and choreographers who have visited the festival.

However, I have also found that a good number of those artists, including Ron Brown, made their Pillow debuts relatively early in their careers and have returned many times since. Consequently, the material that chronicles their multiple visits has grown exponentially, and it is impossible to condense it into a single essay. My solution in this entry is to simply limit my discussion of the artist to his earliest visits to the festival. Fortunately, records of those visits provide some of the deepest insight into his work, because they cover a period of his career (1994 to 2002) when several intersecting factors were having a profound impact on his development as an artist.

He was clarifying his research objectives as he traveled to study the dance, music, and other cultural elements of Africa and its diaspora. He was distilling thematic material that would recur in many of his dances; and he was formulating approaches to that material—for example, the incorporation of the spoken word into his choreography—that would continue to influence his work in the coming years. It was also a period when he was establishing relationships with other artists who would become important collaborators throughout his career. In other words, Brown’s early visits to the Pillow—like those of other African-American artists I have discussed in this series—can be thought of as an essential part of his development as a vital presence in the world of concert dance.

Artistic Influences and First Pillow Visit

At the time Ron Brown and his company first performed at Jacob’s Pillow on August 12 through 14, 1994, he had achieved the remarkable accomplishment of establishing his own dance company at the age of nineteen; he had been creating dances for nine years; and he had premiered over 30 works.Program, Ron Browns EVIDENCE—Jacob’s Pillow 1994—Studio/Theatre, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. He was garnering increased critical acclaim in the U.S., and he had performed and taught in Europe, South America, and Asia. Brown had set out on an artistic journey that was expanding his creative vision; and his distinctive dance language was evolving, as he synthesized the diverse cultural elements he encountered. In these respects, his creative trajectory echoed the research-to-stage process of earlier artists like Katherine Dunham and Pearl Primus. Though Brown was not an academically trained social scientist—like Dunham and Primus, who combined their consummate artistry with their scholarly work—he was developing his own stringent course of study that would take him to Africa, South America, and the Caribbean to research the folkloric and ritual roots of African-diaspora dance and music.

Ronald K. Brown grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn, New York; and he recalls how, as a two-year old, he found himself incessantly dancing around the house—and even in the grocery store, much to his mother’s chagrin. He poignantly remembers, “Two events happened in second grade that were hints of where the journey might lead: During Black History Week, I went to school dressed as Arthur Mitchell, and after my class went to see Alvin Ailey American Dance Center on a school trip, I went home and choreographed a dance in a chair to Nikki Giovanni’s “My Father’s House.’”Ron Brown, 25th Anniversary, Evidence A Dance Company, Ronald K. Brown Celebrates the Journey (Evidence A Dance Company: Brooklyn, NY, 2010), p.14. His childhood choreographic attempts were an early indication that he would have an affinity for incorporating poetry and spoken-word material into his choreography.

Brown also recalls that he had a certain ambivalence about pursuing the serious study of dance. During his high school years, there were periods when he attempted to concentrate on his other interests—writing and journalism—as possible career choices. However, the summer following his high school graduation, he decided to enroll in dance classes at Mary Anthony’s studio, and that began a period of training and searching that shaped the early stages of his artistic development.

Over the years, he would often recount the question one of his friends asked him when he was considering forming his company, “Who is going to tell your grandmother’s stories?”In 1985, Brown formed his company, Evidence. He named it after a solo he had choreographed a year earlier upon the death of a favorite uncle. He later spoke of the solo as “the most heartfelt thing I had ever done.”Terry Trucco, “Dance; The Elusive Spark That Ignites the Choreographer,” New York Times, July 10, 1994, https://nyti.ms/298bJrk. His words are an indication of the central role that themes of family would play in the development of his choreographic voice. Over the years, he would often recount the question one of his friends asked him when he was considering forming his company, “Who is going to tell your grandmother’s stories?”Ron Brown, 25th Anniversary, p. 17. This question seems to have been incised into the artist’s mind, leaving traces of inspiration that arced from the immediacy of himself and his family to the metaphysical implications of the human family/condition.

When Brown was later interviewed at the Pillow by Scholar-in-Residence Maura Keefe, he spoke of some of the earliest experience that shaped his direction as a young, emerging artist; and he also reflected on how he arrived at his commitment to make art that was not meant exclusively for an elite audience of concert dance connoisseurs. He wanted his work to be equally accessible to everyday people, because he wanted to tell their stories.

The group Brown brought to the Pillow in August, 1994 consisted of himself and six other dancers (Ciru Karanja, Crystal E. Simpkins, Cynthia Oliver, Earl Mosley, Niles Ford, and Renee Redding-Jones). A short entry in the printed program revealed some of the sociopolitical issues that Brown was increasingly exploring in his work, including those of race, class, gender, and the implications/challenges of assimilation. The program went on to describe how the company wanted their residencies to reach beyond the boundaries of the theatrical stage. Not only would the artists perform and teach master classes, they would participate in forums and engage with community members to discuss sociopolitical issues that were being explored in the dances they performed. With an approach that encouraged different perspectives, they hoped that forum participants who were acutely affected by the issues—as well as those who were less affected—would benefit from the exchanges.Program, Ron Brown EVIDENCE—Jacob’s Pillow 1994.

This use of art to help initiate change in various communities was an approach that was being explored by other black artists of the period (most notably Jawole Zollar and her Urban Bush Women) and it would continue to be used by socially conscious artists in the coming decades. Brown later alluded to the activist nature of his own work: “When a person steps into the world he represents his families, teachers and ancestors and must move forward with a sense of accountability and responsibility. To be evidence. I wanted Evidence, A Dance Company to present a sense of history and a reflection of the human condition, to be a company in which people could see themselves in stories, music and dance that celebrate who we are.”Ronald K. Brown, 25th Anniversary, p. 17.

Dirt Road: Family, Death, and Same-Sex Desire

Brown and his company made their Pillow debut with Dirt Road/ Morticia Supreme’s Revue, an evening-length work which was a striking encapsulation of the themes and objectives Brown was exploring in his choreography and his community residencies. The program provided little detailed information about the work’s intent, but it did suggest themes of grief and loss by including an elegiac dedication to Brown’s family members and friends who had recently died. The work was an impressionistic account of a family’s “intergenerational journey ‘going home.’” It explored “how a family prepares for loss and reveals the path and the need to return home for peace.”Susan Mehalick, “Ron Brown/Evidence at the Pillow,” Berkshire Eagle, n.p., n.d., Jacob’s Pillow Archives. The reviewer for the Berkshire Eagle also mentioned that a few program notes might have helped the audience better understand the work.

In his essay that discusses Brown’s intent in Dirt Road—Reading “Spirit” in the Dancing Body—dance historian Carl Paris provides a number of details that cannot be gleaned from the program or the video documentation of the Jacob’s Pillow performance.Paris bases his discussion of the work on the printed program and video recording of a performance at Dance Theatre Workshop’s Bessie Schonberg Theatre in New York on October 29, 1995. For example, he lists the characters in the piece; there is Junior, the central protagonist danced by Ron Brown, Buddy (his friend/lover), and family members, Sister/Sister, the Mother, and the Father. Paris also mentions a vocalist, Tamara Allen and a “host/emcee,” in the person of Harmonica Sunbeam.Carl Paris, “Reading ‘Spirit’ in the Dancing Body in the Choreography of Ronald K. Brown and Reggie Wilson” in Black Performance Theory, Thomas DeFrantz and Anita Gonzalez, eds. (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2014) p. 104 He goes on to describe how the work begins: “The opening cabaret scene introduces the characters, starting with Harmonica Sunbeam (a tall and lanky, cream-colored drag queen) as Morticia Supreme. As the hostess, Morticia enters as if opening a show in a club.”Ibid., p. 105. Based on this description, it becomes apparent that the video documentation of the August 1994 performance at Jacob’s Pillow does not include the opening section, for some reason, even though the program lists Sunbeam as “Entertainer/Hostess.” In the hostess character, Brown braided together several strands that run throughout the piece. Morticia’s name, for example, can be read as Death Supreme.

Carl Paris shares another detail concerning the theme of death in Dirt Road, when he tells us that Brown spoke of the reason for the family’s trip home (down South). They have undertaken their journey to attend the funeral of a male relative who has been shot to death by a white sheriff for some “unknown transgression.”Ibid. Their sojourn becomes a metaphor for the ways that African Americans cope with the historical injustices that have been visited upon them, and the ways they find to heal themselves. However, in Dirt Road the family’s engagement with racial oppression is complicated by other matters. By opening the piece with a gender–bending character who seems to be in charge of the evening, Brown purposefully places matters of sexuality on equal footing with matters of race. This expository reference to gay culture helps situate the artist as a gay black man who must deal with race, gender, mortality, and sexuality—all at the same time. In this, Brown emphasizes the fact that he will in no way compartmentalize his life.

Dirt Road includes a duet for Junior and Buddy that is a powerful exploration of how same-sex desire can persist in the face of black family and community taboos against homosexuality. The section reveals the tensions that exist between the repression and the expression of those desires. The partnering between the two men is almost acrobatic, as one flings the other over his shoulder, as they catapult off of each other, and as they take turns holding each other in precarious positions. There is a constant flow of muscular energy that becomes a spectacle of strength and masculine display; but there are also fleeting moments that suggest alternatives to hetero-normative male enactments—an effeminate, mincing walk, a haltingly tender embrace, a gesture tinged with erotic innuendo. In brief encounters, the two men approach each other and then retreat, seeming to toy with passionate desires that are never quite consummated. The duet is a beautifully-crafted statement that delineates the complexities of intimacy and sexuality between two men. It is followed by a solo danced by Brown, in which he is alternately a little boy on his way to church, a mournful penitent, and a joyful celebrant.

The proximity of the duet and the solo seems to further indicate the seamless nature of the artist’s life. This idea was later alluded to in a 2004 Dance Magazine article: “Ronald K. Brown, whose choreography seems to spring from a heart-centered spirituality, says that his spiritual search led him to honor the freedom of being true to himself. ‘In that way,’ says Brown, ‘my spirituality is fed by my being gay.’”Joseph Carmen, “Gay Men & Dance,” Dance Magazine, November 2006, p. 58.

Brown ranged far and wide in his selection of music for Dirt Road. Junior and Buddy’s duet was danced to a collage of recorded music, including a song sung by gay-culture icon Sylvester and a mash-up of house/disco music. Those selections were another indication of the choreographer’s purposeful use of elements drawn from gay club culture. He often referenced those aesthetic choices, including his choreographic affinity for dance movement drawn directly from his club experiences: “As much as possible, I go out to a club at 4:00 a.m. on Saturdays and dance for five or six hours . . . . There are African people in this room who are just dancing, as they might in any basement. Club dancing and traditional dance are related and both have been informing my work.”Ron Brown, “Evolving Traditions,” Dance/USA Journal, v. 18, n.1, May 2001. In this, Brown referred to the common DNA that is shared by different forms of African-diaspora dance and music.

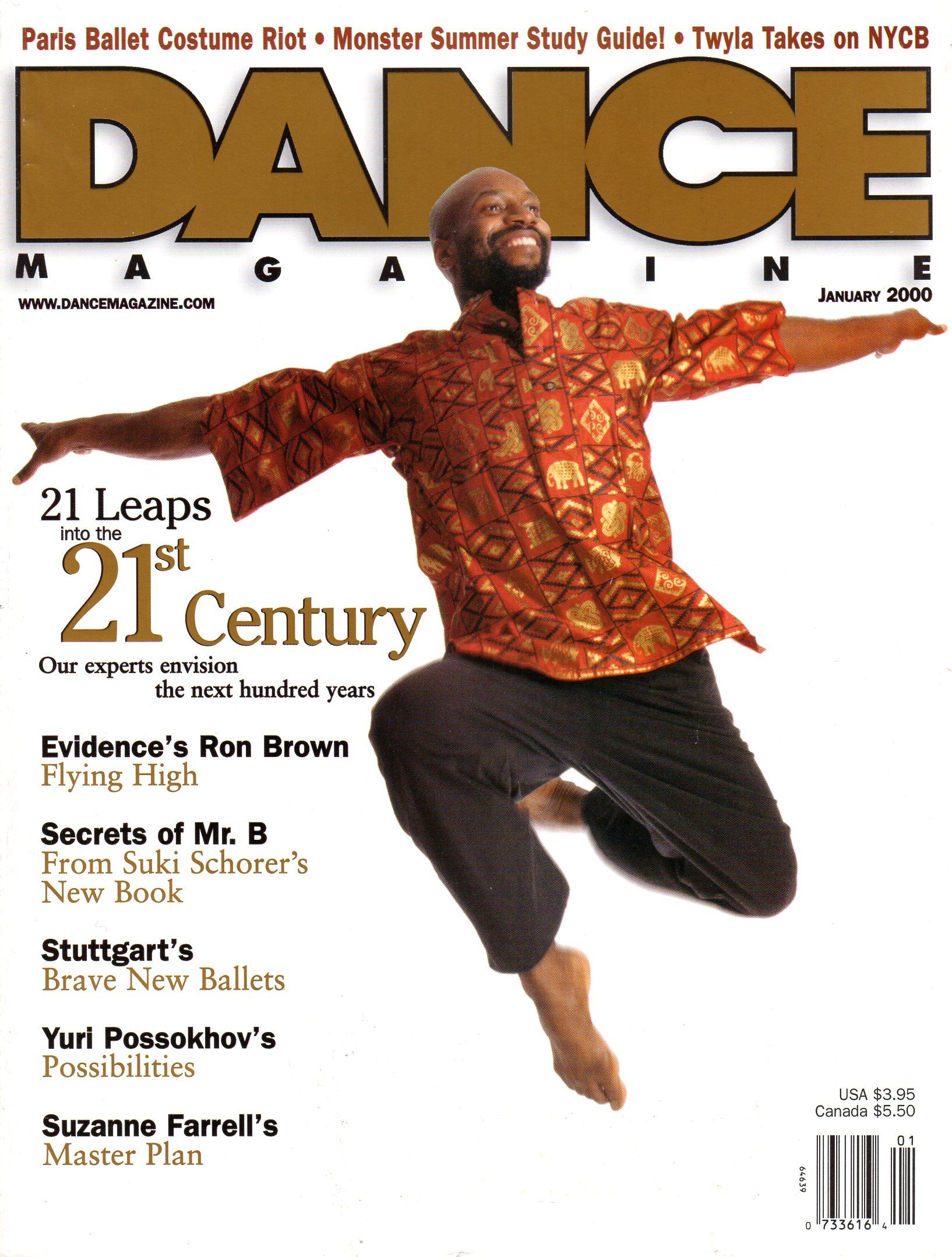

As mentioned earlier, Ronald K. Brown presented his first Jacob’s Pillow concerts during a period when he was solidifying his dance aesthetic. He later reflected, “By 1994, things started to gel . . . . The integration of text with large, powerful movement and gesture, and the fusion of traditional Western African dance with modern dance, began to feel right.”Rose Eichenbaum, “Leap of Faith,” Dance Magazine, January 2000, p. 64. Dance historian Suzanne Carbonneau elaborated on the importance of that year in the PillowNotes of a later program: “It was a trip to Senegal and the Ivory Coast in 1994, however, that weighted Brown’s work so decisively toward the African. There, too, Brown explored not only traditional dance but also social and club dancing, the rhythms, impulses, energy, and movements of which suffused his vocabulary, determined his themes, and charged his staging.”Suzanne Carbonneau—PillowNotes—Jacob’s Pillow Dance—Ted Shawn Theatre—July 6 – 10, 2005—Ronald K. Brown/Evidence and Nnenna Freelon, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. During his trips to Africa, Brown engaged in valuable artistic exchanges with members of Rokiya Kone’s company, Jeune Ballet d’Afrique, and Souleymane Koly’s company, Ensemble Koteba D’Abijan.

Three years later, Brown established another connection with Africa and the Pillow, when he performed Asadata Dafora’s solo, Awassa Astrige (“Ostrich”), at the 65th Anniversary Opening Gala in 1997. As the first African artist to perform at the festival in 1942, Dafora held a special place in its history, and Brown’s performance of his work took place in the same theater where Dafora had performed. It was a stunning moment when the curtain parted to disclose that the space behind the stage was open to the outside, creating a sun-lit, natural backdrop for the performance. With rippling arms, Brown made an imperious progress across the stage, channeling Dafora’s paean to the magnificent bird of the title.

Return to the Pillow

Evidence returned to Jacob’s Pillow to perform from July 8 to July 11, 1999, with a program of three works that revealed the full range of thematic material Brown was continuing to explore. Ebony Magazine: to a village took its name from that mainstay publication of African-American news, culture, and fashion that was first published in 1945 and continues as an online publication today. With that association, the very title of the dance conjured images of the upwardly-mobile strivings, the assimilationist urges, and the narcissistic lifestyle choices that, over the decades, have been embraced by some middle- and upper-class African Americans and rejected by others.

During the creation of Ebony Magazine, Brown collaborated with Wunmi Oaiya, a young emerging artist who composed the music and created the costumes for the piece. As his career evolved, Brown often chose to work with the same artist on a series of different projects, establishing lasting artistic alliances over an extended period of time. In this respect, Oaiya would become one of his most important collaborators. In one section of Ebony Magazine her costumes complement the men’s elegant posturing and strutting, as Brown’s voice is heard reading his own poetry that castigates those who are obsessed with superficiality and materialism. In another section her costumes enhance the women’s sinuous movement and contribute to the depiction of preening fashionistas who are consumed by surface appearances.

In the PillowNotes for the program, Brown spoke of his intent to show that people should abandon a self-centered approach to life and return to an ideal way of living that values the welfare of the entire community more than selfish, individual gratification: “Ebony Magazine is about class and self-consciousness, glossiness and presentation. The suggestion is that the people I am depicting need to get to another place. And finally, by the end of the piece, they do, where they’re not so concerned about how they’re perceived. . . . Ebony Magazine offers a kind of gentle push to a sense of community, a circle, or our all being connected, as opposed to it being all about me . . . .”David Gere, PillowNotes—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Ronald K. Brown/Evidence—July 8 – July 11, 1999—Doris Duke Theatre, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

The title of the second dance on the program, Better Days, referred to an iconic New York bar and dance club that opened in 1972 and catered to a predominantly gay, African-American clientele. In an interview several years after his company’s second Jacob’s Pillow engagement, Brown explained how he had begun to develop the work by asking members of gay and lesbian community organizations what “better days” meant to them:

I wondered…do we think of better days as a time that’s coming, that’s promised to us, or is it some nostalgic feeling we have?”

The question carried enormous weight at the time because of the impact the AIDS epidemic was having on gay communities. Dance scholar/theorist David Gere (who interviewed Brown for the 1999 program’s PillowNotes) described Better Days as “an evocation of gay dance clubs in pre-AIDS New York.”David Gere, PillowNotes—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 1999.

In the book he later published, How to Make Dances in an Epidemic: Tracking Choreography in the Age of AIDS, Gere examines many of the factors that led a number of artists to choreograph works that commented on a troubling time in gay communities across America. As he observed, “From 1981, when the first cases of AIDS (then called GRID, or Gay-related Immune Deficiency) were identified by the Center for Disease Control, through the late 1980s and early 1990s, when AIDS deaths in the U.S. were approaching their grisly peak, the meanings surrounding AIDS actively proliferated, attaching themselves to the dancing body in a perversely symbiotic relationship. More specifically these meanings attached themselves to the male dancing body.”David Gere, How to Make Dances in an Epidemic: Tracking Choreography in the Age of AIDS (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), pp. 40 – 41. Gere then goes on to further elucidate the reasons why gay men, dance, and AIDS, almost became synonymous.

Better Days was another instance of Brown’s reflections on the lives of black men and the complex relationships they develop with each other. In urban communities, gay bars and dance clubs had always functioned both as social centers—places to establish new friendships, reconfirm existing ones, and enjoy both—and as notorious places to find partners for fleeting sexual encounters. But by the early 1990s, the reality of the AIDS epidemic had cast a pall over the locales that had typically served as safe havens for gay men to openly celebrate who they were. In this light, the title Better Days suggests a meaning replete with remembrance and a sense of loss. Those thematic elements were reflected in an opening solo in which the dancer’s movements seemed laden with mournfulness, while the accompanying music—the gospel hymn, His Eye is on the Sparrow—evoked the coexistence of heart-wrenching loss with the possibility of transcending and surviving tragedy. In contrast, the four male dancers in the next section of Better Days depicted lives committed to the expression of an exuberant, celebratory lifestyle.

Here, I will risk speculating that gay members of the Jacob’s Pillow audience (and others who had intimate knowledge of gay culture) may have watched Better Days and understood the multiple meanings reflected in a theatrical performance that suggested the possibility of gay bars and dance clubs being sites that exist solely for the purpose of hedonistic pleasures. On the one hand, that image might have been seen as reinforcing stereotypes of gay existence as the epitome of a superficial and self-indulgent lifestyle; but, on the other hand, such expressions might have been perceived as a communal form of release, part of a healing process that helps ameliorate the stresses of living in an extremely homophobic society. Yet, there may have been others in the audience who did not maintain either of those points of view, and instead they simply enjoyed the spectacle of four amazingly-energized men dancing rhythmically and buoyantly, spinning in and out of movement vortices, and luxuriating in the euphoria of the moment.

In Better Days, Brown also continued to develop some of the choreographic devices he had begun to explore in the men’s duet in Dirt Road, including interjections of fleeting effeminate gestures and movement phrases that were infused with homoerotic innuendo. For example, there is a moment in the dance when the four men line up across the front of the stage with their backs to the audience; then—as if they have exposed their genitalia—they all glance down to “check out” each other. Their dancing also included brief, but suggestive, pelvis-to-buttocks contacts. Those moments flickered like signals, guiding the audience through the representation of a transgressive space where sexuality between men is not only permitted—it is celebrated. Yet, everything unfolded with good-natured joviality, and some members of the audience responded as if they were in on a naughty—but tolerable—little joke.

Moving the audience to a contrasting emotional pole, the third work of the concert, Water, opened with the unsettling spectacle of dancers flinging themselves violently at each other. They seem to be in the throes of some undisclosed trauma that has left their white clothing splattered with what appears to be blood. It is an image that has powerful emotional import; but, at the same time, it leads one to wonder what message the choreography is meant to convey. It is a question of creative intent that only the artist can answer. Fortunately, dance enthusiasts who visit the Pillow are given opportunities to gain insight into the creative processes of an individual artist.

During a PillowTalk with Maura Keefe on July 7, 1999, Brown described how he worked on the opening section of Water with his dancers. He tried to motivate them with the idea that they belonged to a family/community in which some of the members needed to convince others that they were making dire mistakes in their lives. To create the desired images of confrontation and intervention, he encouraged the dancers to literally jump on each other’s backs and wrestle each other to the ground. Brown explained that he called this “snatching”—the point being that sometimes you have to use tough love to “snatch” someone back to reality.PillowTalk—Poetry in Movement—1999/07/07—DVD #1267, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. He alluded to the same idea in his interview with David Gere, when he discussed the conceptional underpinnings of Ebony Magazine. In that case, indulgently self-involved individuals needed to be “snatched” back to their senses. He also spoke of a similar situation with a family member, describing how he once had to throw his younger brother out of the house to teach him a lesson.David Gere, PillowNotes—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 1999.

As Water unfolded, one group of dancers and then another moved to the back of the stage, where each dancer removed part of their clothing and appeared to try to wash away the red stains. It is a powerful opening for a work layered with deeply emotional images, and those shifting images were enhanced by the words of poet Cheryl Boyce-Taylor. From his early childhood Brown had always felt the need to express himself through his own poetic writings, and during a later period—1983 through 1985—he found a group of kindred spirits when he connected with a collective of gay poets that included Essex Hemphill, Donald Woods, Craig Harris, Colin Robinson, and “several other incredible writers.”Ronald K. Brown, 25th Anniversary, p. 17.

During the creation of Water, Brown worked closely with Boyce-Taylor, as he wove her poetry into the piece. When they were interviewed at the Pillow, they discussed some of the ways they had engaged in a symbiotic creative process. Although he had worked with the integration of text and movement before—including dances in which he used his own poetry—Brown described how he had developed a new way of working during the creation of Water. He realized that Boyce-Taylor clearly wanted to be present in the studio while he choreographed, and this inspired him to work back and forth between her and the dancers:

“Cheryl was there, and I would make up the movement with Cheryl there . . . . And, I would have to go line by line and then go work it out with the dancers. And, then they would have to remember the material. And, I would have to rehearse them in the material; and then go back over to Cheryl and say, ‘o.k., can we go to the next line?’” So, it was kind of a tedious process, but that was the only way I could see to do this particular piece.”PillowTalk—Poetry in Movement.

A type of dance-theater that created a unique sensory experience for the audience by melding movement with music and the spoken word.What resulted was a type of dance-theater that created a unique sensory experience for the audience by melding movement with music and the spoken word. In the coming years, several of his most important works would adhere to that aesthetic.

With the creation of Water, Brown continued to display a remarkable ability to synthesize a wide spectrum of historical and cultural material drawn from African-diasporan sources. Sometimes those sources were as near as his personal experiences as a black male living within a nurturing circle of family and friends. He often spoke of the ongoing influence that his family’s church affiliation exerted in his life: “I grew up in the church in Brooklyn. My great uncle founded a church, so it was there for us. You had to go. It was just the way to be connected to God. My grandmother and my mother always made your relationship with God a priority. . . . Even when I left home and didn’t attend church every Sunday, my relationship to God was very important to me.”David Gere, PillowNotes, July 1999.

Guided by the influences of his early religious upbringing, Brown created works like Water that acknowledge the sanctity of many different types of spiritual practice: “I believe in God. And Jesus Christ was a prophet. Mohammed was a prophet. There are some incredible lessons in the Buddhist religion. I use whatever oracle and whatever lesson could assist my staying on track. I collect spiritual practices and exercise them as much as I can.”Ibid. Moreover, because he had continued to steep himself in the traditional music and dance forms that are an inextricable part of West Africa religions, he stretched the spiritual trajectory of his work from the specificity of individual black lives (like his grandmother’s), to African cosmologies, to universal truths.

A New Africanist Millennium

When the company returned in July of 2000, they performed two works that indicated Brown’s progress toward achieving the aesthetic goals he had set for himself years earlier. He continued to explore his distinctive movement vocabulary that brought audiences to the edge of their seats; and he continued to refine all of the aspects of the total-theater environment he envisioned. The first work on the program, Upside Down, was part of a longer work, Destiny, he had originally choreographed in collaboration with Jeune Ballet d’Afrique Noire and premiered in 1998.

A description in one of the company’s brochures sheds light on the thematic message of individual growth that is sustained over a lifetime by of a caring community:

The first section of Upside Down begins with a premonition of a community mourning. The second section of the dance continues as a race that reflects the impetus that drives an individual towards their own destiny. The score begins with Malian vocalist Oumou Sangare’s, Kun FeKo (The Uncertainty of Things), a song which says the destiny of a child is in god’s hands, and the role of the community is to stand guard and guide. The remainder of Upside Down is set to Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s song of the same title, which tells a story of chaos and corruption because of the abuse of power and the ever strong desire for wealth. The dance ends with a solo statement of an individual’s readiness to make the transition to the ancestral burial ground, followed by the final procession of the community in their collective response in support of the individual.Company Brochure, Evidence: The Ritual and the Journey of Dance, 2002, pp. 2 – 3, Author’s Collection.

The second piece on the 2000 program was commissioned by the Pillow. High Life was yet another colorful entry in Brown’s choreographic diary in which he remembered the history, art, and culture of black people. It opened with a brief suggestion of African-Americans on the auction block, as the dancers moved to Oscar Brown Jr.’s chilling refrain, “Bid Em in, Bid Em In.” The soundscape continued with the voice of poet Nikki Giovanni layered over gospel music. The choreography conjured images of men and women traveling/dancing along emotional paths that take them to different waystations on their journey through history. High Life evoked the chronicles of various migrations—to America (the forced one), from South to North, from rural backwaters to urban centers, even back to Africa. These were moments in time when black people carefully packed up their spiritual and cultural belongings—as best they could—and carried them to different place.

In High Life, Brown’s dancers embody the hope and euphoria that is voiced in spirituals and in gospel music; they luxuriate in the sensuous phrasing of the blues and jazz. The juxtaposition of those sacred and profane musical expressions—and the dances that they inspire—is a testament to the idea that Saturday night and Sunday morning celebrations in black communities form a continuum of earthly and heavenly delights. Brown’s choreography plays back and forth between the secular and the religious—entities that have traditionally been viewed as polar opposites in Western societies. Moreover, in his work, those entities present themselves as indissoluble elements in an all-embracing lifeforce.

In addition to the African-American music Brown used in High Life, the music of Nigerian artist Fela Anikulapo Kuti further exemplified the complexity of cultural transmission throughout the African diaspora. The PillowNotes in the program consisted of an insightful essay by Suzanne Carbonneau in which she discussed the circuitous routes that black music and dance have traveled over several centuries. In Fela’s ebulliently polyrhythmic music, one can hear African musical forms that migrated to America, where they evolved into African-American musical forms. Those, in turn, migrated back to Africa, where—in combination with other music of the diaspora, for example that of Cuba and Jamaica—they had a marked influence on artists like Fela:Suzanne Carbonneau, PillowNotes—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Doris Duke Studio Theatre—July 13 – 16, 2000, Ronald K. Brown Evidence, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

In High Life, Brown traced this cross-pollination through the music of the late Nigerian musician, Fela Anikulapo Kuti (popularly known as Fela), who began his career in the ‘50s as a singer with a highlife band. By the ‘60s Fela had developed his own instantly identifiable sound, which he first called highlife-jazz, and eventually, Afro-beat. Melding highlife, soul, jazz, and traditional Nigerian music, Fela’s music became internationally recognized for its rhythms, while it inspired Nigerians with its heroic stand against political corruption and injustice.Ibid.

Carbonneau’s last statement refers to Fela’s important role as an artist whose social and political activism in the 1970s and 1980s led to vicious attacks on him and his family by the Nigerian military government; eventually he was imprisoned for almost two years. During his tumultuous life, he used every aspect of his artmaking to confront the various abuses of power—governmental, corporate, and religious—that he saw decimating the lives of black people around the world.

Upside Down and High Life were two works that encapsulated the highly expressive and dynamic approach to movement that Ron Brown had been refining during his career. A striking example of this is his exploration of the polycentric possibilities in a dancing body. An arm or a leg is impulsively flung/released in one direction and the rest of the dancer’s body seems to follow, only to be quickly re-directed when another part of the anatomy decides to take over. Likewise, the snap/toss of a head can send a dancer reeling in a new direction. This physical dynamic lends a mercurial quality to Brown’s movement vocabulary, because one is never quite sure where the next movement phrase will be initiated in the dancer’s body, where the unpredictable flow of physical energy will be resolved. I see this as a movement metaphor for a state of possession, the seemingly uncontrolled, trance-like state of a worshiper whose consciousness has been taken over by a spirit—a god. This idea is especially salient in regard to Brown’s body of work, because his choreography is so heavily influenced by African and African-diasporan cultures in which religious ecstasy is an expressive component of the people’s dance and music forms.

Another characteristic of Brown’s movement vocabulary is its exquisite gestural quality. In our daily lives, the use of our hands and arms, the shrug of our shoulders, and the tilt of our heads all vivify the deepest meanings of the words we use. Brown incorporates similar gestural communication in his choreography. A frequent viewer of his work becomes accustomed to seeing the gesture of a dancer with their arms extending diagonally downward to the side of their body, elbows slightly bent. The flattened palms of their hands are either facing forward or upward. It is a gestural question—Why did you? How soon will you? When can you? It is a way that he enables his dancers to speak with each other, in movement conversations that are central to many of his works.

However, it is not only the body’s appendages and extremities that make gestures in his dances. When I see a dancer with his or her head thrown back, fully exposing their neck, opening their chest, and arching their back, I see a bodily gesture. One that clearly delineates a spiritual state of supplication, or joy, or resignation, as in, “God I am in your hands.” Very often, Brown extends this particular bodily disposition into an explosive turn in the air, or he uses it as a static punctuation at the end of a movement phrase. For me, both of those options indicate the choreographer’s fascination with the dichotomy between movement that surges on as if it might never end, and sudden stillness that continues to pulse with the afterlife of the body’s previous animation. This, too, is full of metaphorical significance.

The juxtaposition of movement and stillness is, of course, an element of all dance. Sometimes when dancers are on stage, they dance; and at other times, they are still. But Brown’s use of this polarity strikes me as having a special place in his aesthetic. He has often described how his company’s name, Evidence, relates to our being in the world. We are all evidence of a constellation of things—our personal histories, our family heritage, our people’s strivings. Dancers in his works, then, represent the same fulsome meaning of individual existence. They dance their evidence. They dance as evidence. Quite often, they stop abruptly. They seem to stand at attention, waiting as a servant to be called to attend someone’s needs, or as a witness to be called to testify. In these static moments, they channel accountability as they observe each other’s danced evidence. Watching them watching each other is a mysterious and fulfilling experience.

Ronald K. Brown returned to the Pillow in 2002 to participate in A Tribute to Katherine Dunham. From June 24 to 27, the series of panels, master classes, workshops, and performances drew participants from throughout the U.S. and abroad to honor one of America’s most important artists who had dedicated her life to dance performance and scholarship, humanitarian efforts, and political and social activism. At the opening concert, Brown danced a solo, In Gratitude, for Ms. Dunham while she sat on stage. And his company performed an excerpt from Walking Out the Dark, Part II.

Overlapping with the Dunham activities, Evidence performed from June 26 to 30, in a program that reprised Upside Down and an excerpt from Water. The work that closed the program, Walking Out the Dark, brought many of Brown’s aesthetic signatures to the stage in heightened form. For example, the opening section consists of four dancers standing in a circle on a darkened stage. In their own turn, each moves into a barely-lit central area, where they converse with another member of the group in the gestural dance language I described earlier. They communicate with flurries of movement, as they confront, question, cajole and otherwise express a gamut of disturbing emotions. The music for the opening section—first Philip Hamilton’s and then Sweet Honey in the Rock’s—suggests the southern locale that Brown visited in Dirt Road, but, as if traveling to another location, the music eventually segues into the rhythmic percussion of Francisco Mora.

In the post-show talk, Brown discussed some of the background material that inspired Walking Out the Dark. He explained how, in 1996, he set out to write a book of poetry and essays that was based on an individual’s letters to his brother, his sister, and his mother. He also spoke of how the letter-writer (ostensibly Brown himself) realized that there was a disturbing distance in his relationships with his family members that placed him in a kind of exile. He sensed that there was a lack of mutual caring between them. “There’s some anger in the relationship, a need for forgiveness.”Post-show Discussion—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Ted Shawn Theatre—June 26 – 30, 2002—Ronald K. Brown/ Evidence — DVD #1475.2, Jacob’s Pillow Archives. Brown’s thoughtful reflections, again, underscored the centrality of familial themes in several of his works.

He also commented on the second section of Walking Out the Dark, which—in striking contrast to the first section—had a folkloric quality that was enhanced by the dancers’ colorful costumes. Brown recounted how he and his company had traveled to Cuba several months earlier, first teaching and working with several companies in Havana and then traveling to Santiago, where they worked with Ballet Folklorico Cutumba. He spoke of the rich experiences they shared with Cuban artists who were steeped in religious traditions wherein spirits manifest themselves in the dancing bodies of worshippers. His growing understanding of kindred spirits throughout the African diaspora reaffirmed his belief in the value of his work, and he explained that he felt a calling to connect the spiritual traditions of the people he encountered in different locations around the world. This was of special importance to him because of the lack of spiritual grounding he sensed in contemporary America.Ibid.

Ronald K. Brown’s artistic journey shows us the many ways that a dancing human body functions both as a representation of our flesh-and-blood material existence, and as a symbolic and spiritual representation that transcends our physical existence. The themes of his work reflect a constellation of human concerns—religious beliefs, social and political issues, conflicts over gender and sexuality, and other matters that we address in our daily lives. He brings all of those things together in work that is exquisitely seamless, profoundly communicative, and breathtaking in its multi-faceted beauty. Over the years, he and his company members have been able to share the abundance of their artistic gifts with audiences at Jacob’s Pillow, and that is yet another indication of the festival’s valuable contributions to the world of dance.