Racial Proscriptions and Early Influences

From an early age, Talley Beatty was aware that every aspect of African-American life was dominated by the constraints imposed by entrenched racial practices that had long been a part of America’s social and political infrastructure. Such practices had led his father to pack up his family in Cedar Grove, Louisiana and relocate to Chicago, because he fought the sale of his land to the white men who wanted it. When he became interested in dance, Talley found that the racial proscriptions of a Chicago dance studio resulted in him being forced to take classes in a room that adjoined the main studio. Separated from the other students, he followed along as best he could while watching the teacher’s directions from his segregated space.

From the 1930s and 1940s onward, such slights affected aspiring black dancers in different ways. Some became more determined than ever to pursue professional training in their chosen field. Some used the stage as a platform for protest, as Katherine Dunham did when she told an audience in Louisville, Kentucky that she would not return to the city until she could perform in a theater that was not racially segregated.VeVe A. Clark and Sarah E. Johnson, eds., Kaiso! Writings by and about Katherine Dunham (Madison, WS: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), p. 255. And others—with different degrees of success—transplanted their careers to Europe, with the hope of finding fewer racial barriers to interfere with their art-making.

Another dynamic of the time functioned as a springboard for Talley Beatty to pursue a successful career in dance. Though few and far between, there were pioneering black artists of the 1930s and 1940s who were able to embrace and mentor black youngsters who were interested in the arts. Katherine Dunham played such a role when she invited twelve-year-old Talley Beatty to study in her Chicago studio, later taking him into her company and giving him the kind of performance opportunities that laid a strong foundation for the young artist’s career.

While dancing with Katherine Dunham’s company, Beatty encountered the kinds of racial prejudice that were common to black performers who toured during the 1940s. Finding adequate housing for company members was a constant problem. Sometimes it was solved by making arrangements with local members of the black community to house the performers in their homes. At other times, the dancers were housed in substandard accommodations. During a tour on the West Coast, Beatty angrily confronted Dunham and her manager, Sol Hurok, concerning rooms that contained little more than dirty mattresses thrown on the floor. He later mentioned the altercation as the reason that he left the company.Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2002), p. 133. Over the years, he would become known for having a volatile temperament, and the confrontational side of his nature would also affect his relationships with Ted Shawn.

His First Visit to the Pillow and Southern Landscape

At the time Beatty and his company first performed at Jacob’s Pillow on July 24, 1948, he had begun exploring other aspects of his career as a performer and a choreographer. In 1946, for example, he appeared in a revival of the musical Showboat along with Pearl Primus, Joe Nash, and Alma Sutton, who had been a lead performer in Asadata Dafora’s Kykunkor. Beatty began presenting his own choreography at small venues such as Charles Weidman’s Studio Theater; and by 1948, he had also choreographed an extended work that opened the way for his continuing development as a major choreographer on the national and international dance scene.

Southern Landscape—one of two works Beatty brought to the Pillow on his first visit—was inspired by a literary source that echoed the same kind of racial disenfranchisement that had made his father leave Louisiana with his wife and young son. Beatty recalled reading Howard Fast’s best-selling novel Freedom Road, published in 1946 and set during the Reconstruction era. He spoke of being profoundly moved when he learned how freed slaves and poor white farmers worked together and began to establish successful communities in the South after the Civil War. The work of those interracial coalitions was thwarted, however, because white-supremacist power brokers lobbied Washington for the removal of federal troops that were stationed throughout the South to keep the peace after the war. The resulting vacuum contributed to the rapid growth of the Ku Klux Klan and its agenda of nullifying efforts toward racial equality.

In Southern Landscape Beatty drew on Fast’s novel that delineated the historical contexts and traced the chain of events leading up to the destruction of one such cooperative community in South Carolina. The story reaches a violent turning point when the farmers fight a pitched battle with the Ku Klux Klan to protect three of their men who have been wrongly accused of a crime. The result is that their farms are burned to the ground and most of them are slain.

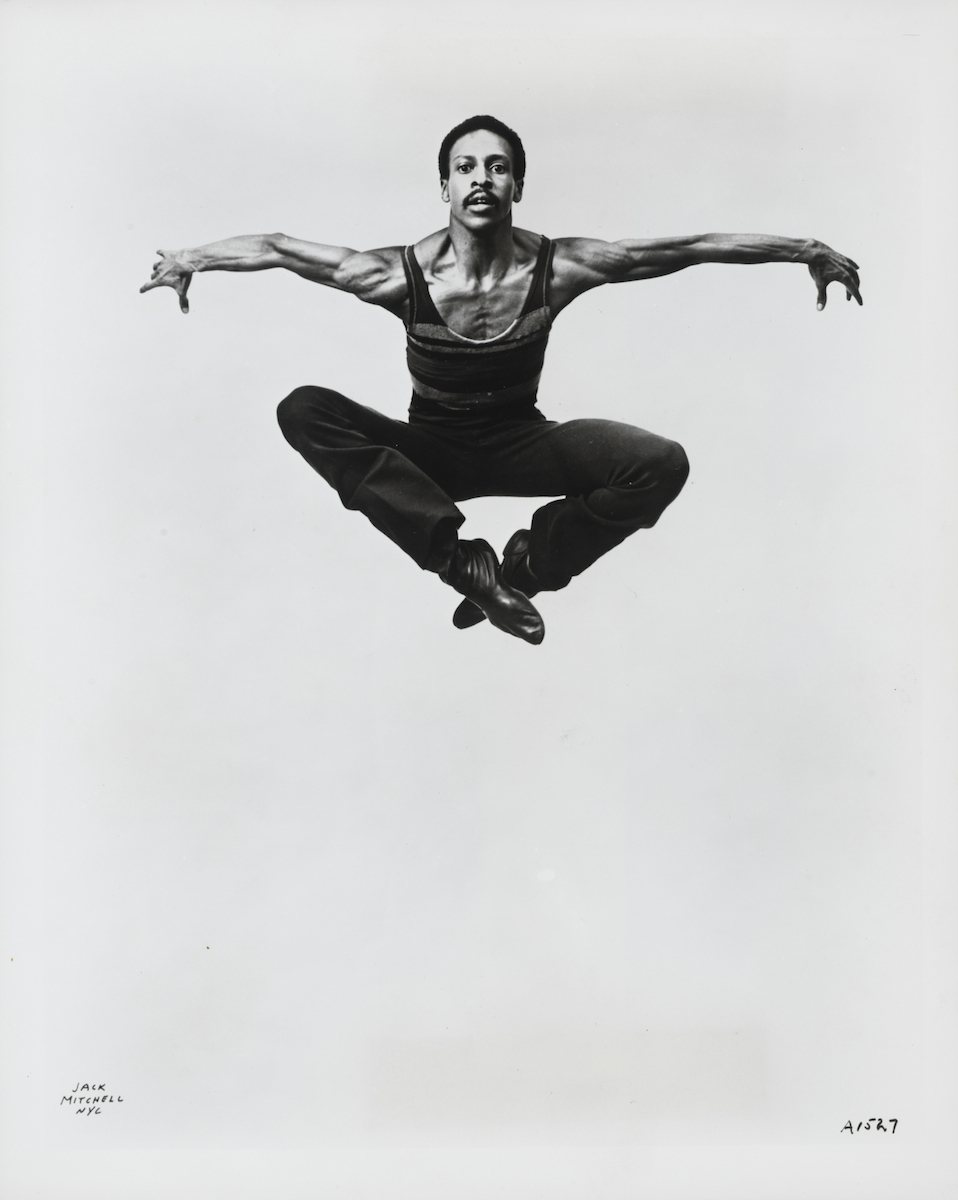

Beatty was able to distill the novel’s emotional themes in a five-part dance that moved from resistance, through desolation and grief, and ended on a note of hopeful affirmation. In the first section, “Defeat in the Fields,” Beatty uses the dancers to capture images of working, struggling, fighting, and finally succumbing to forces that are too strong to overcome. In the opening section, Beatty’s dancers also display his signature choreographic style characterized by movement that appears to be inhumanely fast and is propelled by a furious energy that seems to be wrenched from the dancer’s bodies. The dancing seems to have an underlying anger and desperation that echoes the tragedy depicted in Fast’s novel. “Defeat in the Fields” ends with the sound of a barrage of gunfire—one of the few literal notes in the dance—and we see a pile of lifeless bodies center-stage.

The second section, “My Hair was Wet with the Midnight Dew,” refers to a time when the community was under siege, and they had to bury their dead at night when darkness gave them some protection from the Klan. The dance is a quartet for two men and two women, and the motifs of outstretched arms and trembling hands continue the theme of the people’s desperation, because they cannot understand the depth of the hatred that has reduced their once thriving community to a final fight for survival.

The third section, “Mourner’s Bench,” is the best known section of the dance, and it is a tour de force that became a symbol of Beatty’s powerful performance style during his early years.

The black and white film that was taken during his first visit to Jacob’s Pillow captures images of his inventive choreography, much of which centered on his precarious balances on an eight-foot long wooden bench, followed by his breathtaking descents to the floor. On the film, his dancing is also framed by the rustic, wood exterior of one of the old farm buildings at the Pillow, creating a kind of poetic completeness in view of the dance’s thematic material. “Mourner’s Bench” was also a solo that became a staple in companies like the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company. (See excerpts of both below, as well as a shorter excerpt with sound added.)

In the closing sections of Southern Landscape Beatty used his artistic license in the sense that Howard Fast’s novel ended with the massacre of the farming community, while the dance ends on a note of hope and affirmation, conveying the message that the tragedies of the Reconstruction period would be overcome and the dreams of equality would eventually be fulfilled.

The second dance that Beatty contributed to the 1948 concert was Rural Dances of Cuba, a folkloric piece in five sections that displayed another aspect of his choreography during the period. At the time, his company manager was encouraging him to capitalize on the popularity of work that was derivative of Dunham’s revues. As Dunham’s biographer Joyce Aschenbrenner points out, “North American audiences and critics were intrigued and entranced by the Dunham Company’s artistic and skillful portrayal of what were viewed as ‘exotic’ materials.”Katherine Dunham, p. 132.

Beatty’s manager hoped the same would be true when they toured Europe, and a few months after the Pillow performance, the company premiered a concert program in Göteborg, Sweden that included dance material from Cuba, Haiti, and South America, as well as dances steeped in African-American source material such as Southern Landscape, Boogie Woogie Improvisations, and Blues Scenes.

His Second Visit to the Pillow and Conflict with Ted Shawn

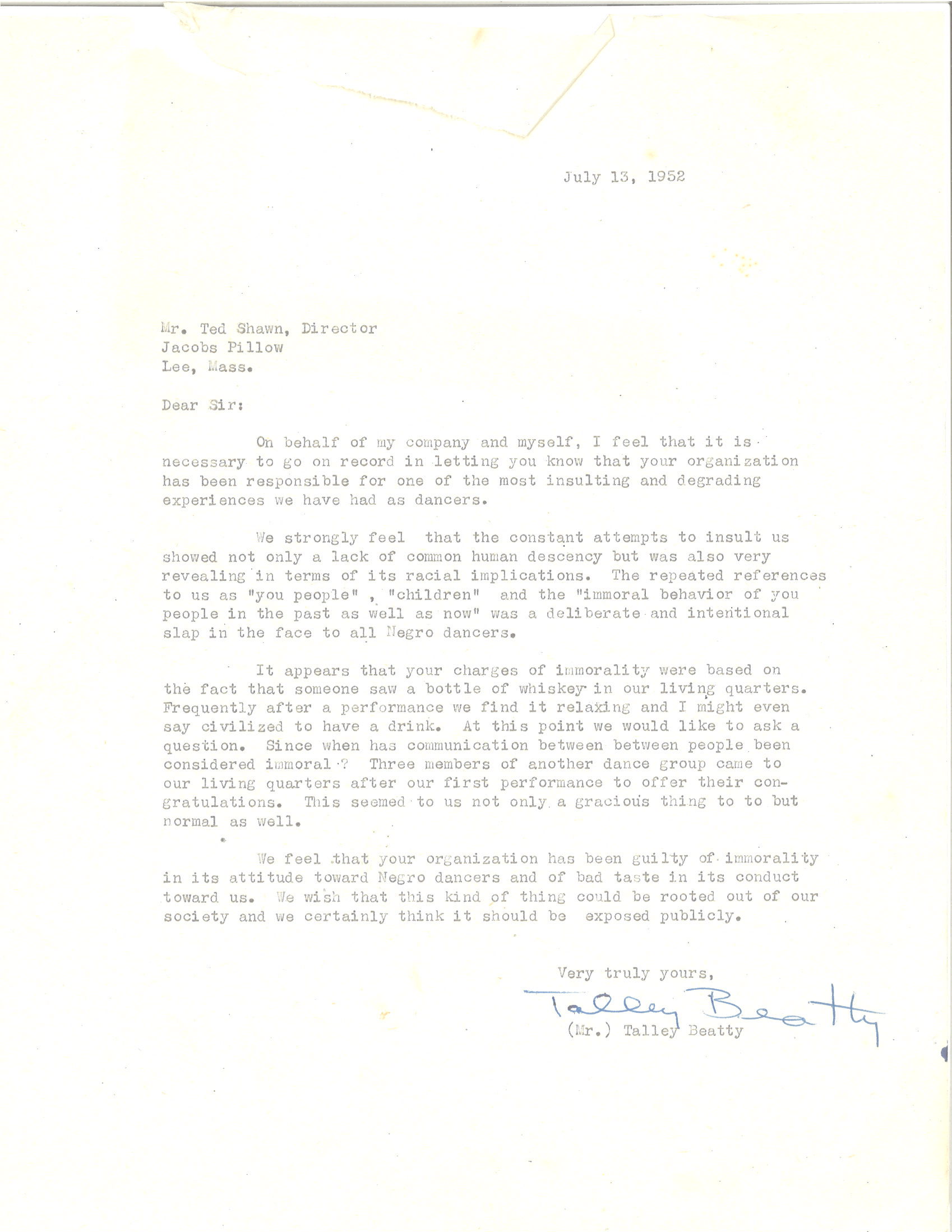

By the time Beatty came to Jacob’s Pillow for his second appearance, on July 11 and 12, 1952, he had added a number of professional accomplishments to his resume, including a European tour. The 1952 visit was also the occasion when Beatty and Ted Shawn became entangled in a conflict that led to heated exchanges. No doubt, the situation was exacerbated because of Beatty’s volatile temperament and his understandable sensitivity to situations that appeared to be tinged with racial discrimination. The story of the two men’s conflict is clearly documented in an exchange of letters between them. On July 13, 1952, Talley Beatty wrote:

On behalf of my company and myself, I feel that it is necessary to go on record in letting you know that your organization has been responsible for one of the most insulting and degrading experiences we have had as dancers.

We strongly feel that the constant attempts to insult us showed not only a lack of common human descency (sic) but was also very revealing in terms of its racial implications. The repeated references to us as “you people,” “children” and the “immoral behavior of you people in the past as well as now” was a deliberate and intentional slap in the face to all Negro dancers.Letter from Talley Beatty to Ted Shawn, July 13, 1952, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

The letter went on to describe the incident that led up to Beatty’s accusations. Apparently, someone had seen a bottle of whiskey sitting on a table in the dancers’ living quarters; in addition, several dancers from another company had come by to congratulate Beatty’s dancers after their performance, and the celebration became noisy. Beatty infers that Shawn reacted to the group’s after-show unwinding as if it were immoral.Ibid.

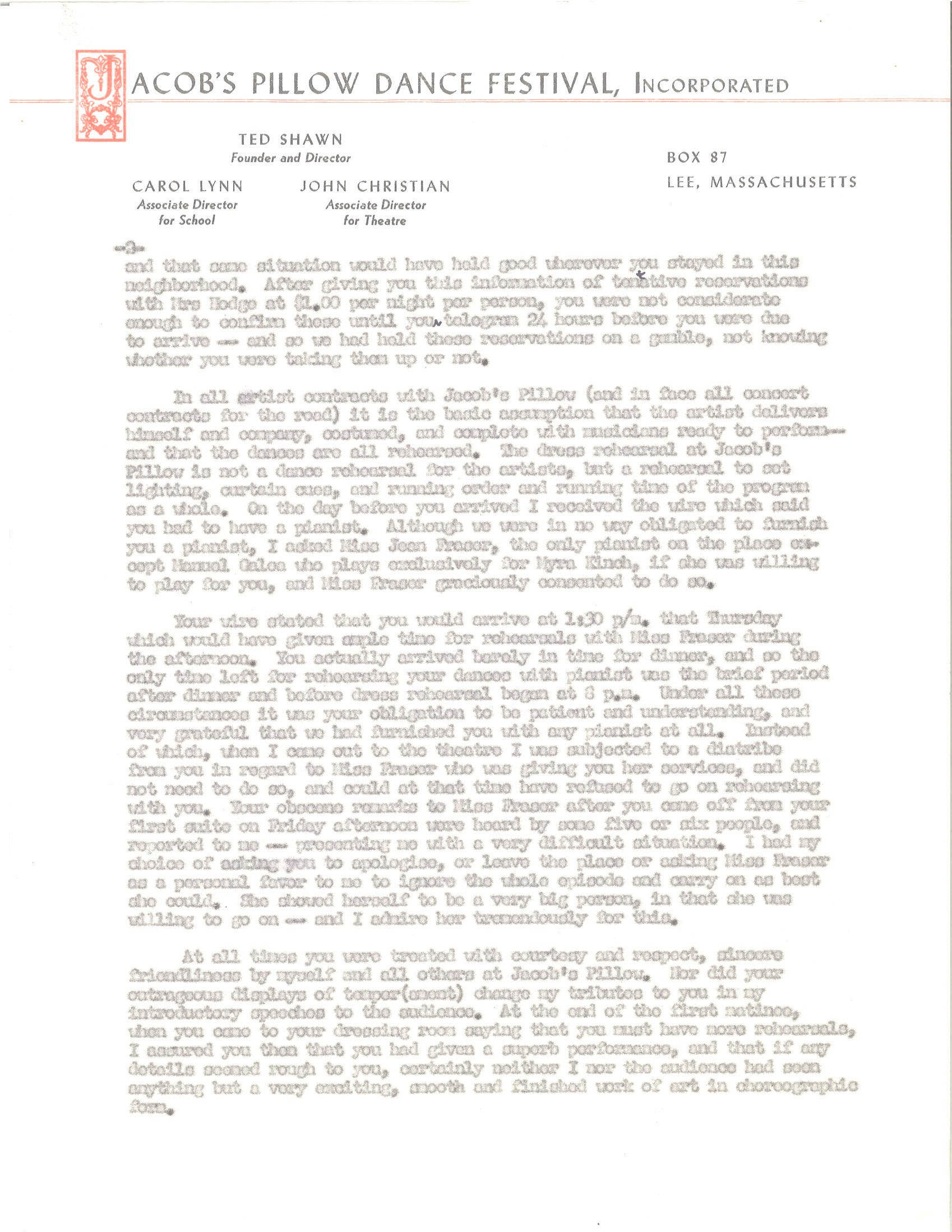

In contrast to Beatty’s brief letter, Shawn’s reply, dated July 21, 1952, seems to be characteristic of his style of written communication—extremely long-winded and meticulously detailed. Shawn’s letter began with a reminder that he had gone out of his way to accommodate Beatty’s request to appear again at the Pillow for that season; and that he had waited a month for the signed contract to be returned. When Beatty explained that they could not afford the expensive off-site housing in the area, Shawn made arrangements with a Mrs. Hodge to board them dormitory-style across the road from Greenwater Lodge. (He goes on to say that Mrs. Hodge is a “New England woman, with typical New England standards.”)Letter from Ted Shawn to Talley Beatty, July 21, 1952, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Shawn then listed a series of other problems he had to solve to accommodate Beatty’s last minute requests. For example, there had been no contractual agreement to provide a pianist, but Shawn provided one after receiving a wire the day before the group arrived. Because the company arrived late on the day of dress rehearsal, their time with the pianist was rushed, and Beatty was dissatisfied with the rehearsal. Following that, Shawn said he had to endure a “diatribe” from Beatty in regard to the pianist’s work, and the pianist herself was subjected to “obscene remarks.”Ibid.

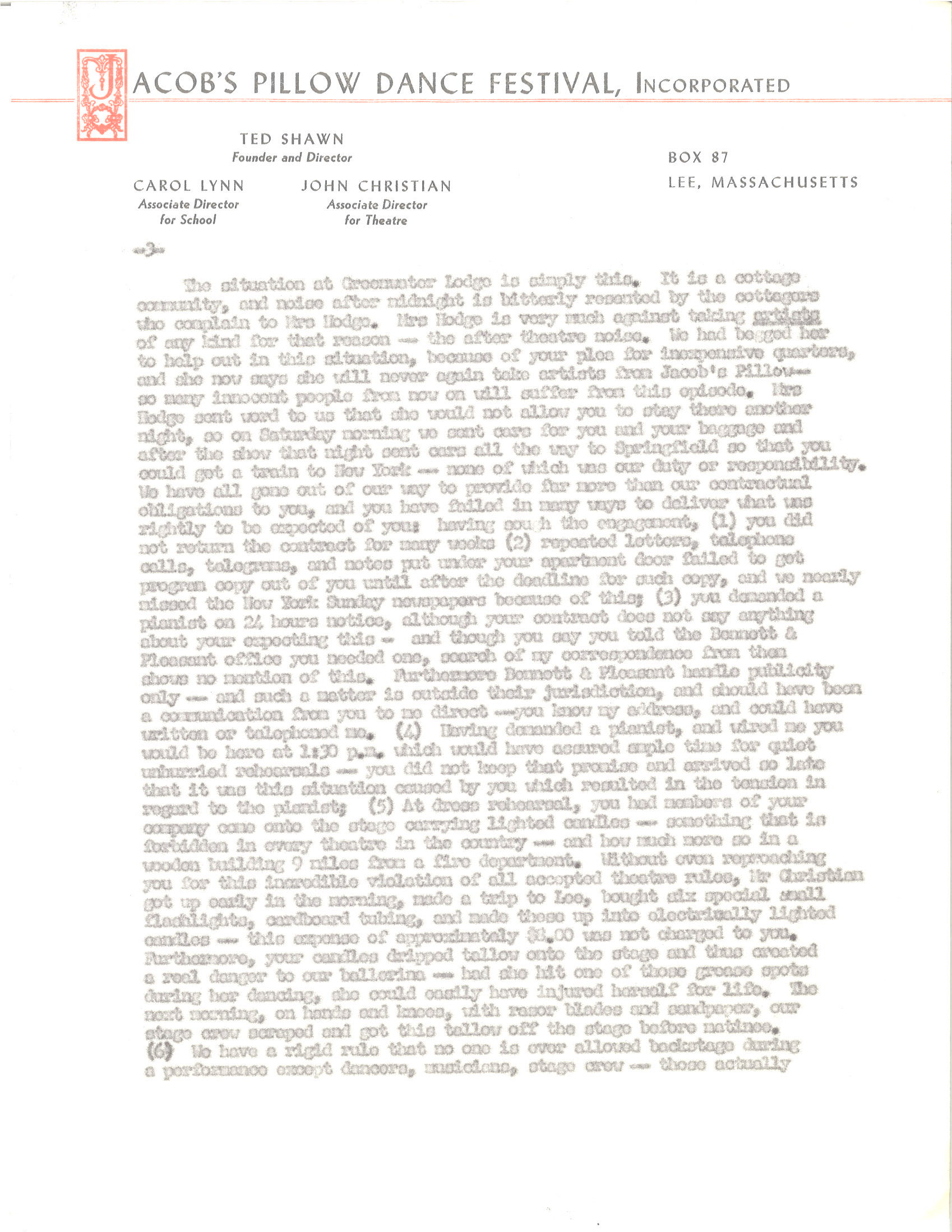

On the fourth page of his single-spaced letter, Shawn summed up the problems he had previously mentioned concerning Beatty’s visit, and he added a number of additional points that indicated how he had gone the distance to accommodate what he saw as unreasonable behavior on the artist’s part. Shawn then went on and began addressing the racial aspect of Beatty’s complaints:

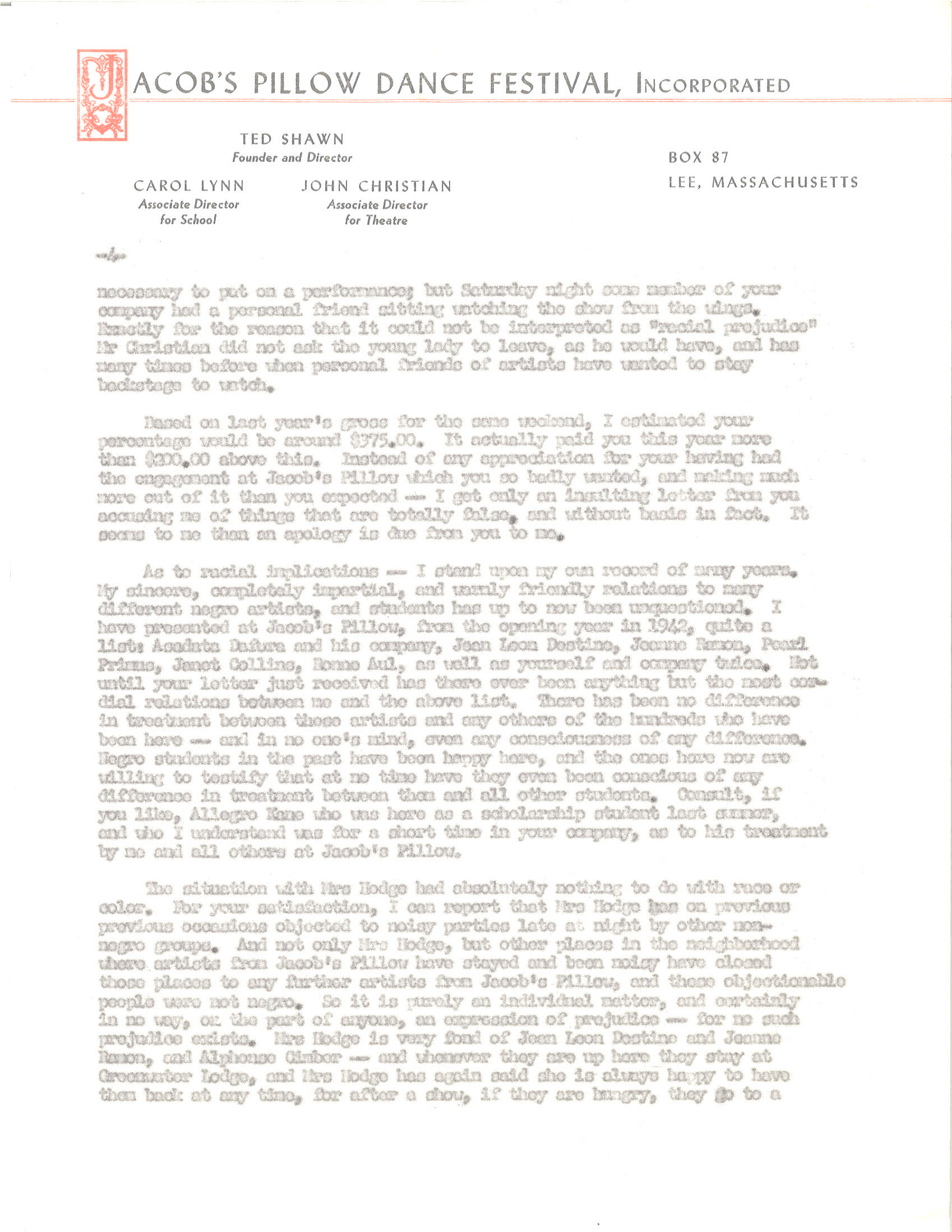

As to racial implications—I stand upon my own record of many years. My sincere, completely impartial, and warmly friendly relations to many different negro artists, and students has up to now been unquestioned. I have presented at Jacob’s Pillow, from the opening year in 1942, quite a list: Asadata Dafora and his company, Jean Leon Destine, Jeanne Ramon, Pearl Primus, Janet Collins, Ronnie Aul, as well as yourself and company twice. Not until your letter just received has there ever been anything but the most cordial relations between me and the above list. There has been no difference in treatment between these artists and any others of the hundreds who have been here—and in no one’s mind, even any consciousness of any difference. Negro students in the past have been happy here, and the ones here now are willing to testify that at no time have they even been conscious of any difference in treatment between them and all other students.Ibid.

He goes on to state that Mrs. Hodge’s reactions had nothing to do with race, since there had been prior complaints about dancers’ after-performance noise, and many of those had to do with artists who were not black. He continues to underscore his point that there was absolutely no racial prejudice involved by pointing out that Mrs. Hodge has always been happy with boarders like Jean Leon Destine, Jeanne Ramon, and Alphonse Cimber.Ibid. Warranted or not, it seemed that Shawn reacted to Beatty’s complaint by becoming extremely defensive and, perhaps, overstating his case.

Beatty’s company opened the July 11 and 12, 1952 concert with Island Holiday, followed by Cousin, which the program indicated was choreographed by Lawaune; and their first section closed with Region of the Sun. The company’s other offering was Ritual in which Beatty danced “the one possessed.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Eleventh Season—1952.

It appears that Beatty, at this point, was continuing to present the kind of colorful and “exotic” folk material he had been encouraged to create after leaving Dunham’s company. The balance of the concert consisted of the grand pas de deux from Don Quixote and performances of José Limón’s Concerto Grosso and Doris Humphrey’s Night Spell.Ibid.

His Third Visit to the Pillow and Phoebe Snow

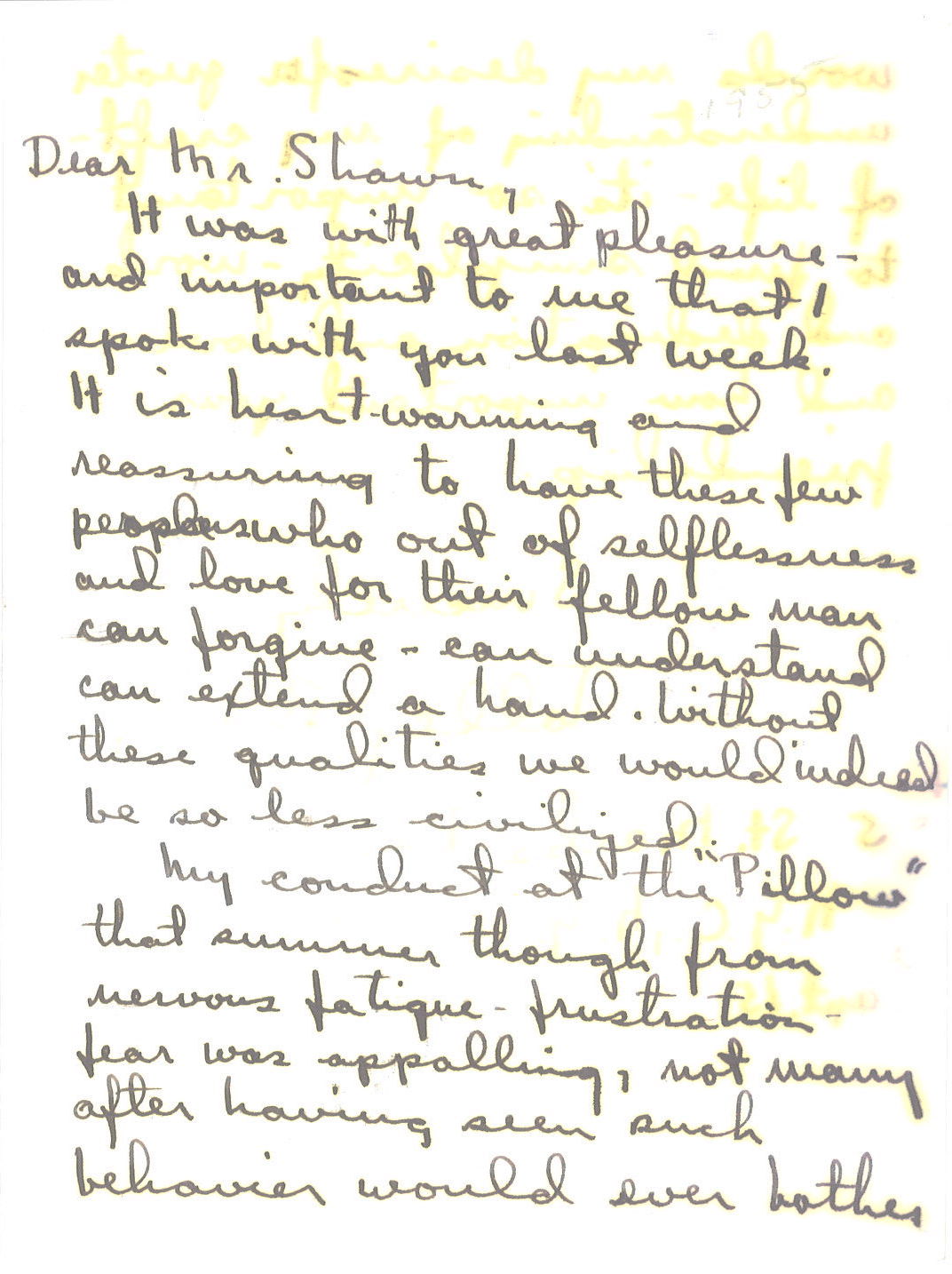

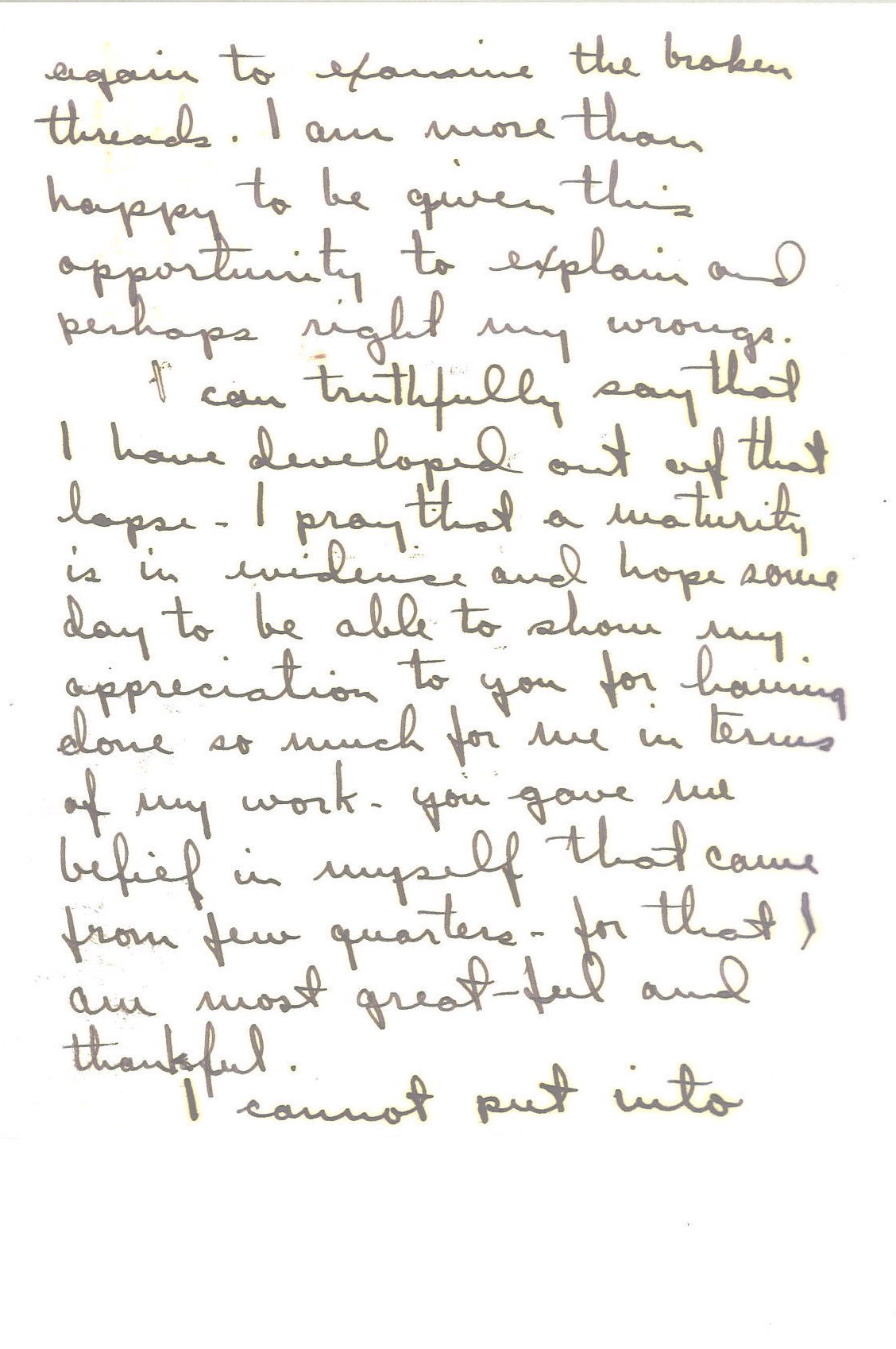

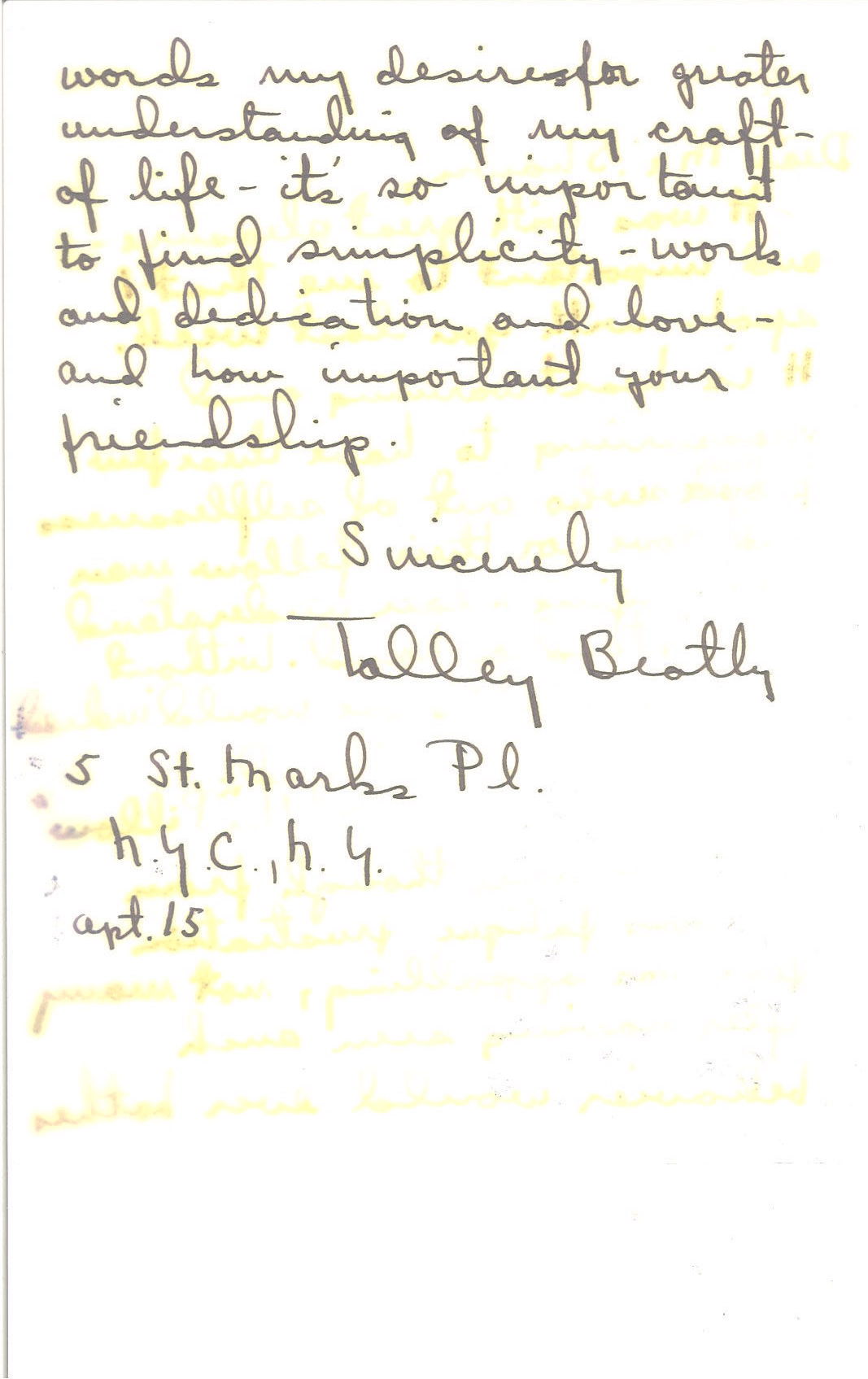

At some later date, Beatty made an effort to mend his strained relationship with Ted Shawn, as reflected in the following conciliatory words:

. . . . It is heart-warming and reassuring to have these few people who out of selflessness and love for their fellow man can forgive—can understand, can extend a hand. Without these qualities we would indeed be so less civilized.

My conduct at the “Pillow” that summer though from nervous fatigue – frustration – fear was appalling, not many after having seen such behavior would ever bother again to examine the broken threads. I am more than happy to be given this opportunity to explain and perhaps right my wrongs.Undated letter from Talley Beatty to Ted Shawn, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

Beatty continued by saying that he had matured since then, and he hoped it was evident. He concluded by expressing his appreciation for Shawn’s friendship and his support over the years.Ibid.

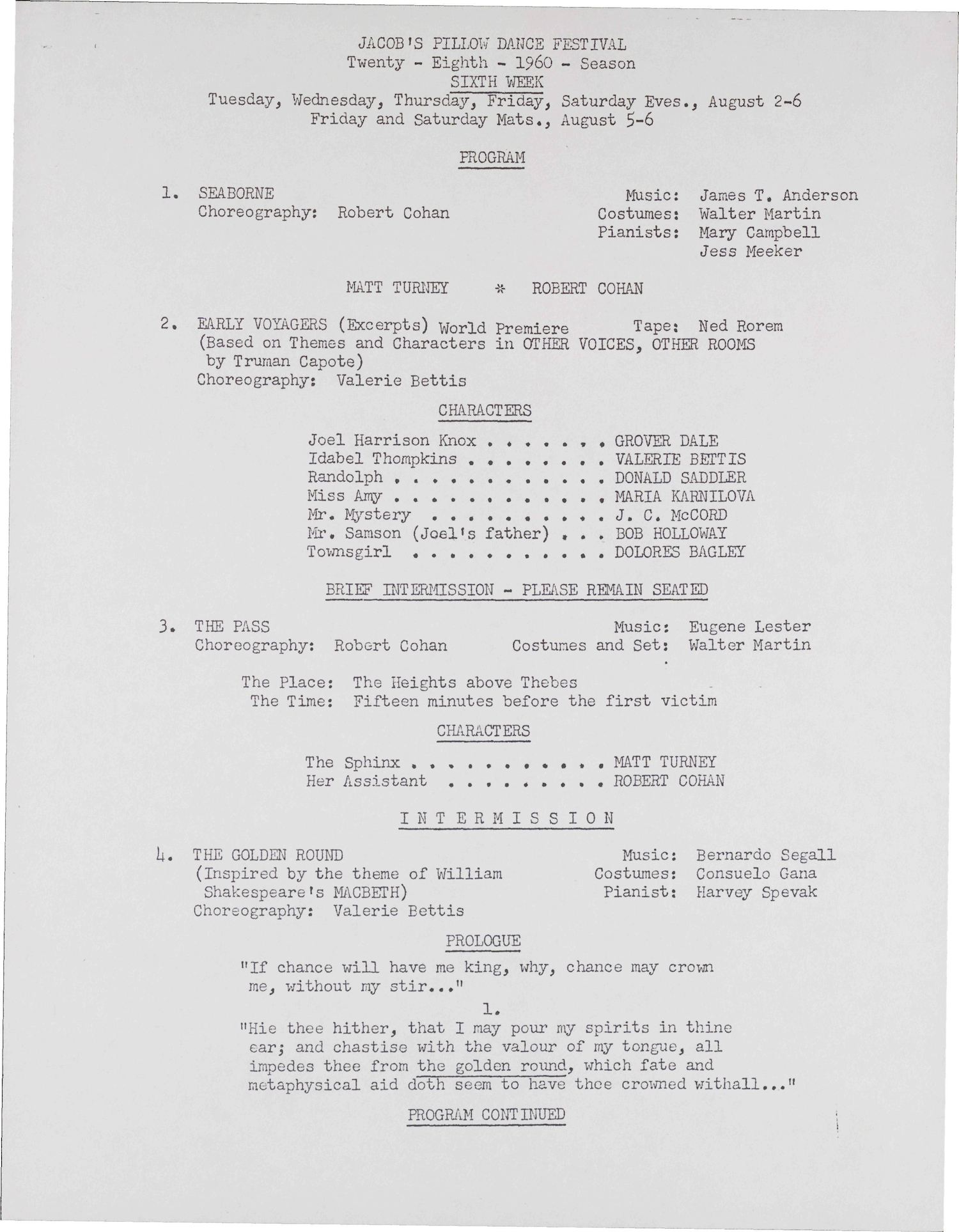

The letter is undated, but it seems logical that Beatty would have written it some time prior to his third appearance at the Pillow on August 5 through 6, 1960. His company of nine returned with members that included Georgia Collins, Joan Peters, Nat Horne, and Charles Moore. They performed one piece, The Road of the Phoebe Snow.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Twenty-Eighth—1960 Season.

The interesting title of the newly-choreographed work was taken from the name of a passenger train that ran along the tracks of the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad near Beatty’s Chicago neighborhood. The dance depicted the brutal impact that an oppressive urban environment can have on the young people who live there. The choreography delineated the relationships of young lovers who were trying to survive in the midst of the destructive individuals surrounding them. Again, Beatty’s fast-paced, hard-driving movement embodied the emotional and psychological tensions of his subject matter.

Phoebe Snow also exemplified another aspect of Beatty’s unique approach to dance movement; the choreography consisted of a seamless blending of ballet, modern dance, jazz dance, and movement reflecting the African-diaspora dance he had learned with Dunham. This synthesis was a mainstay of his approach to his choreography, in spite of the fact that he had repeatedly been singled out by critics for his “distressing tendency to introduce the technique of the academic ballet” into his performance when he was in Dunham’s company.John Martin, “The Dance: A Negro Art,” New York Times, Feb. 25, 1940, Sec. 9, p. 2. Of course, this amalgam of different dance forms was also a characteristic of many African-American choreographers, then as now. But, Beatty’s flawless sense of choreographic phrasing enabled him to segue from the crisp linearity of balletic movements to the visceral strength of modern dance to the rhythmic isolations of jazz and African-diaspora dance in amazingly quick and smooth successions.

His Choreographic Works, an Important Influence at the Pillow

Beatty did not maintain a company of his own after 1955, so he never brought another group to the Pillow as he had in earlier years. Instead, he concentrated on creating new works and setting his existing works on other companies such as the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which became a major repository for his choreography. Beatty’s sporadic visits to the Pillow, in later years, occurred when he attended special events and was interviewed about his early days at the festival. However, his presence was regularly felt as his works were performed by different companies over the years. The Road of the Phoebe Snow was performed by the Boston Ballet in August, 1968; and the program note—as if trying to explain why a dance that originally had an all-black cast was being performed by an all-white cast—stressed the universality of the story: “This universal story of conflict, not color, was inspired, composed, and choreographed by all negro performers until premiered by the Boston Ballet.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—1968 Season.

Other companies that presented Beatty’s work at the Pillow included Ballet Hispánico performing Caravanserai on August 17, 1984.

The Dayton Contemporary Dance Company performed “Mourner’s Bench” during their residency of August 7-11, 1990, and two years later Philadanco performed the full-length Southern Landscape when they visited from June 30 to July 4, 1992. Philadanco also performed A Rag, a Bone, and a Hank of Hair on June 24, 1993, and the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Company performed Come and Get the Beauty of it Hot on August 24, 1993.Various Programs, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 1984, 1990, 1992, 1993, and 1994. A program note for the latter paints a succinct impression of the choreographer’s work: “Talley Beatty’s sizzling, sultry suite of jazz ballets fuses elements of African, Caribbean and classical dance. Congo Tango Palace, the last section of the work, represents an imaginary ballroom in Spanish Harlem.”Program, Jacob’s Pillow 1993—25th Anniversary.

Other Beatty works that have been seen at the Pillow include La Divinador, performed by Dayton Contemporary in June 1994 and Ellingtonia performed by Cleo Parker Robinson’s company in August, 1996. This very likely makes him one of the artists whose work has been performed most frequently at the festival. Moreover, it is an interesting distinction, considering his early altercations with Shawn.

Talley Beatty like Donald McKayle—another African-American artist who performed at the Pillow during its early years—had a career that included choreographing for television and Broadway shows. In the latter category, Beatty created dances for Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope (1970), Ari (1971), and Your Arms Too Short to Box with God (1977). In this aspect of his career, he joins the list of African-American and European-American concert dancers who sometimes balanced their higher artistic callings with work in more commercial arenas. Because he was so inclusive in choosing his movement sources, he probably felt comfortable following this path. In the end, however, his stunning choreography spoke for itself, no matter what its setting.

The different factors that shape an artist’s personality are complex, and they also affect his or her artistic trajectory. As we have seen evidenced in his work at Jacob’s Pillow, Beatty’s life as a black man who grew up in a racially-divided America was a lasting and volatile influence on the dances he created.

PUBLISHED October 2017