The word is out

You're doin' wrong

Gonna lock you up

Before too long

The Origin Story

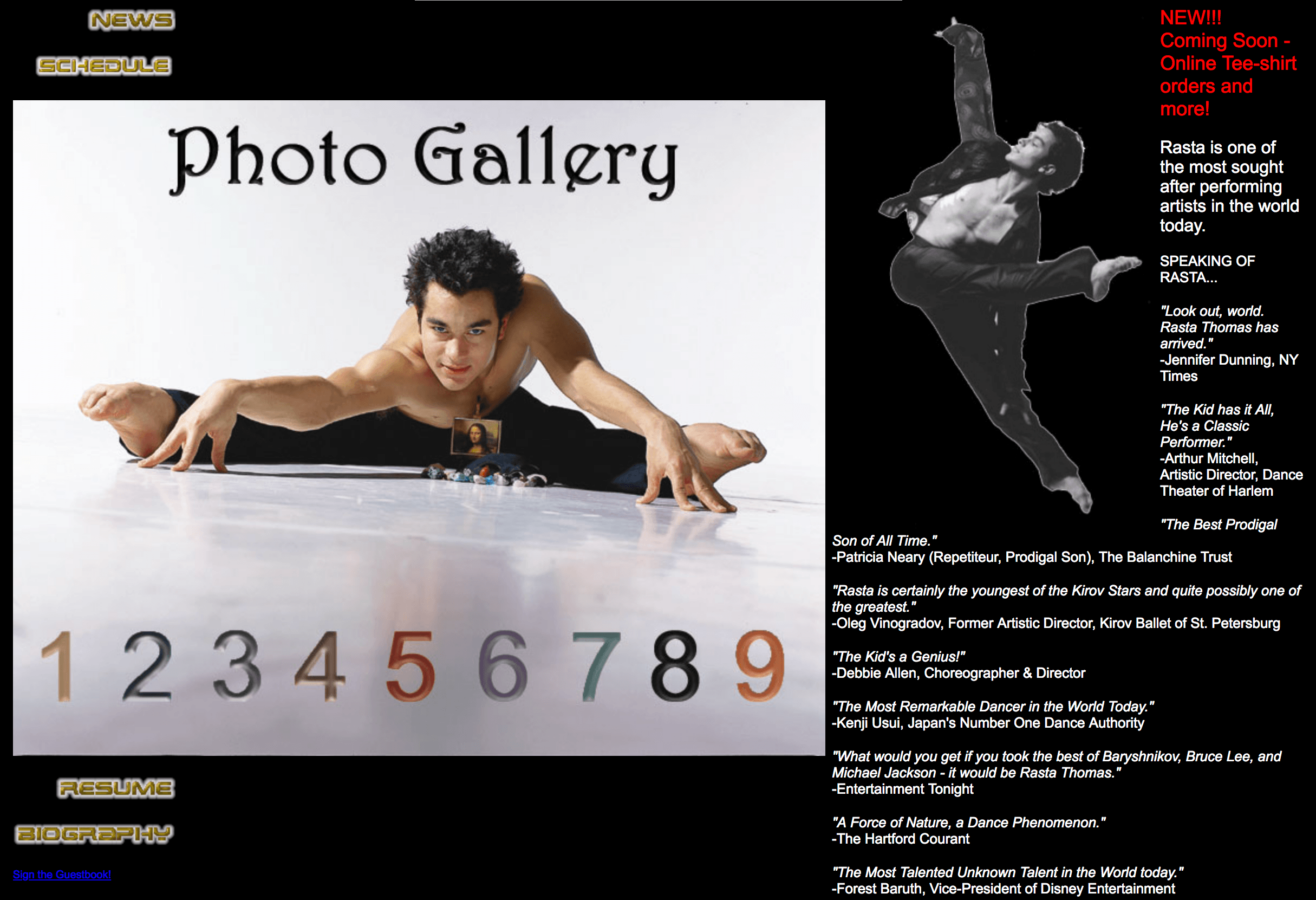

USA International Ballet Competition Gold Medalist and dance virtuoso Rasta Thomas was one of the first people in the dance world to have a website. The Internet Archive has snapshots of www.RastaThomas.com dating back to December of 1998, and the site was a marvel of the late ‘90s web. There was a custom Rasta Thomas usenet forum and a guestbook with a single comment: “Spiffy Web Site! Needs more pictures, though.” The bio page states that Thomas has earned multiple black belts, and the home page (“Rasta Thomas Home Page!”) quotes Entertainment Tonight: Rasta Thomas is, “What would you get if you took the best of Baryshnikov, Bruce Lee, and Michael Jackson.” The footer asks that anyone interested in hiring Thomas for martial arts and dance performances should fax their inquiry to a Maryland number, and includes a note that the site was produced in collaboration with “Rasta and Dan Thomas (Rasta’s Dad).” There is a promise of Rasta Thomas-themed merchandise, coming soon.

To scroll through the first decade of RastaThomas.com is to observe the trajectory of an artist ascendant. The calendar page of the 2007-era site demonstrates international success and acclaim: In February, Thomas would appear in Diaghilev tribute performances in Tokyo, in May he would be “Prince Siegfried” for the Orlando Ballet and then guest with the American Ballet Theatre. The last engagement on the page is notable: July 26-29, 2007, “Rasta debuts his company ‘Bad Boys of Dance’ at Jacobs (sic) Pillow.”

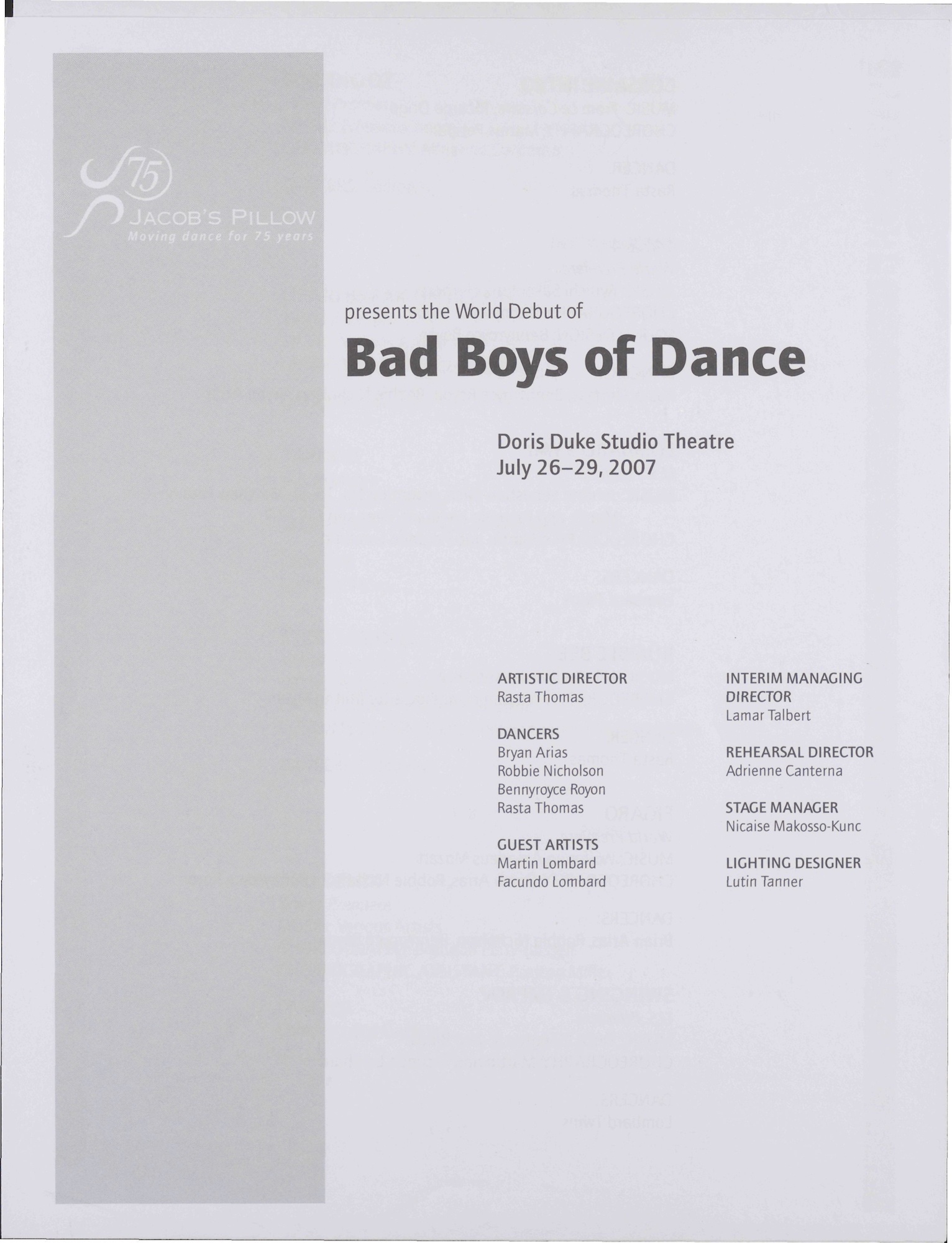

Thomas had spoken with Ella Baff (then Executive Director of the Pillow) about pulling together a premiere for the 75th anniversary festival, and as an homage to the Pillow’s founder, Ted Shawn, he suggested a project that (per the now defunct www.BadBoysOfDance.com) would “push the boundaries of male dancing today.” Baff gave the green light and Thomas hired an ad hoc company of men to perform as the Bad Boys of Dance.

The Debut Performance

The company debuted in the summer of 2007, and the opening moments of that first show are instructive. The performance starts not with Baff’s customary welcome but with Thomas barreling onstage executing virtuosic switch leaps and grand jetés, a rendition of the male solo from the coda of Petipa’s Le Corsaire. Corsaire has an impenetrable plot—something about pirates—but Thomas’s solo projects bravura and balletic hunkyness. He’s shirtless, amply muscled, handsome, and exudes simultaneously Apollonian and bravura gorgeosity. Thomas dashes on for a minute, but before exiting, gestures to center stage as though another dancer were about to take the space. He glides off. Nobody else enters. The music continues, awkwardly juxtaposed with an empty stage. The Corsaire coda has a strict structure, and the Petipa choreography stipulates a woman should be doing fouetté turns, but the woman never shows. Thomas, acting confused, stumbles back on stage saying “Cut, Cut, what’s going on?” His ignorance and stupor are played for laughs. “Where’s my partner? …. There’s a girl that’s supposed to be right here…”

The scene jokily frames the evening’s performance, with Baff then walking on stage to explain to Thomas (with the forced hokeyness of a veteran culture warrior having fun) that, so sorry, there’s been a mixup and there are unfortunately no girls tonight, only bad boys. Dance insiders, however, might have guessed the identity of the intentionally absented woman: Adrienne Canterna, Thomas’s Kirov-trained, longtime dance partner. The two had married that spring with a child due that fall, and thereafter briefly considered an incarnation of the “Bad Boys” project called “The Bad Boys and Pretty Girls of Dance.” On opening night, however, other than a brief, spoken allusion to Ted Shawn from Baff, the audience was more or less left to their own devices to ascertain what made these “boys” so “bad.”

“Bad” “Boys”

A Q+A page on the then-operational BadBoysOfDance.com posed the question to Thomas, “Why did you name your company Bad Boys of Dance?” Thomas aspirationally responded: “I was labled (sic) a Bad Boy from the start for not making my career with any 1 company.” (Thomas had, somewhat famously, not joined any one dance company on a permanent basis but opted instead to be a frequent guest soloist. In an email, he noted dancing for 25 companies before founding the Bad Boys.) “Now that I have a company of my own, you better believe that we are going to stray from the path of tradition and break all the rules along the way.”

Referring to one’s own self as a “bad boy” was, by 2007, already a trope burdened by associations from decades of pop culture use. For example, the 1995 Will Smith / Martin Lawrence cop comedy, Bad Boys features a scene where Smith’s character tells Lawrence’s that he drives “like a bitch.” Lawrence responds, “My wife know I ain’t no bitch. I’m a bad boy.” Lawrence and Smith then sing the reggae song, “Bad Boys,” having deflected accusations of sissydom and mutually reaffirmed their apparently fragile masculinity. The song, “Bad Boys,” was performed by the self-proclaimed “Bad Boys of Reggae,” Inner Circle (their website: www.BadBoysOfReggae.com) and has themed the TV show Cops for some 30 years, cementing associations of the term with physical violence. The “Bad Boys” song was featured in the Pillow performances too, sampled at the show’s sudden conclusion when a dancer mimed the use of a pistol, then an automatic weapon, to mow down the other dancers to the sounds of gunfire. The man with the mimed gun is left standing, while the rest lie on the ground as though dead.

Thomas’s company was much anticipated but poorly received by critics. Rebecca Ritzel, writing for the Washington Post some years later, wrote that it was “tough to remember that the Bad Boys debuted at the venerable Jacob’s Pillow dance festival.” Roslyn Sulcas wrote for the New York Times that the Bad Boys take “the prize for ‘worst choreography,’ ‘trashiest spirit,’ ‘most tasteless’ and ‘utter vacuousness of concept’… It is a strong contender for the ‘worst of all time’ top spot.” Dance journalists razzed the company for being too flat, too frontal, to emotive, too obvious, and too fierce, but indeed, those very traits made the work (and work like it) massively popular on the Internet. The Bad Boys continue to have a sizable following, and by some measures, can be seen as an early shaping influence on the aesthetics of digital dance performance. By this metric (and like Thomas’s early online presence) the theatrical frontality of the Bad Boys was arguably ahead of its time and ideal, if not always for the stage, then for the screen.

Recent Developments

After the initial swirl of publicity around the Bad Boys, there is a reprieve from the public eye. Thomas and Canterna divorced and, per Thomas, while he owns the Bad Boys of Dance, she now maintains an incarnation called the Bad Boys of Ballet, which had 2018 performances in a high school auditorium in a Maryland suburb and a state-run theater in New Jersey. I hadn’t heard much of Thomas until he filed a lawsuit against the American National Ballet (ANB), a company he was hired to direct which had calamitously collapsed before a single public performance.

By phone, Thomas recounted being told by company management that there was a seven million dollar budget, but being startled to later learn that those funds had yet to be raised and that the entire company (notably including Sara Michelle Murawski) had been hired preemptively. Thomas describes signing a contract (which I later saw, fully executed, exactly as Thomas recounted it) to be ANB’s Executive Artistic Director, but after expressing concerns for the financial state of the company, he received an email a week before his start date stating his services were no longer needed. According to the Post and Courier, the company refused to honor the severance clause of the signed contract that they disavowed exists, and Thomas sued for damages.

ANB cited misdemeanor assault charges leveraged against Thomas in Arizona, domestic violence cases in Maryland, and a civil conviction in California as rationale for the termination, to which Thomas’s lawyer told the Post and Courier that Thomas pursued all contract negotiations “truthfully and honestly,” though acknowledged that his bipolar disorder was an occasionally contributing factor. Details of these suits are available through public state filings, though the ANB episode is the first journalistic mention I’ve found of either Thomas’s bipolarity or history of violence. The company (such as there ever was one) quietly settled the suit in the fall of 2018, leaving doubtful the veracity of the initiative to begin with, and having left the careers of many dancers thoroughly disrupted.

Legacies

Still, this moniker of the “bad boy” is an ambivalent emblem that references multiple, divergent perceptions of Thomas’s career. In this, Thomas’s work rhymes with other, earlier men in dance such as Vaslav Nijinsky and Ted Shawn, illustrating that bad boys are an intergenerational historical enterprise in dance. These are men who resist convention, whose personal lives are complex and at times contradictory, who were capable of acting nobly and badly, peacefully and violently, and who produced dances with lasting, unpredictable impacts. Thomas started the “Bad Boys” as an homage to Ted Shawn, and in his career, evidences the multifaceted nature of that legacy.

PUBLISHED January 2018