When there is a person, there is a problem. When there is not a person, there is not a problem.

Archiving and Loss

It’s the sort of thing that happens to researchers all the time: you’re searching in an archive for what you think you’re looking for, and by luck, you discover something far stranger and substantially more interesting than whatever you’d sought in the first place. In the summer of 2017, I was digging through the Jacob’s Pillow Archives for media pertaining to Merce Cunningham’s Biped when I serendipitously pulled up a 1999 video of media artists Shelley Eshkar and Paul Kaiser (the duo who created Biped’s ghostly projections) as well as a third, entirely unexpected individual: Patrick Moore. Moore had been a member of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), was then the Director of The Estate Project for Artists with AIDS, and is presently the Director of The Warhol Museum. The presence of Eshkar and Kaiser in the footage made sense, but not Moore, whose radical politics seemed at odds with the supposedly apolitical choreographies of Cunningham. In his brief remarks, Moore described a skunkworks pilot project that I had never heard of: a collaboration between him, Eshkar, Kaiser and the choreographer Bill T. Jones to use nascent technologies of motion capture to preserve the dances of artists affected by HIV / AIDS. Moore spoke passionately about the possibilities of the work, about the particularly pernicious effects AIDS has on the medium of dance artists—their bodies—and how an obscure, biometric technology called “mocap” (short for motion capture) might very well revolutionize dancemaking and, by extension, the archival practices of the Western dance tradition.

Dance history is, in many respects, a study of how such efforts fail. The impermanence of the work—that the embodied dance form disappears as soon as it comes into existence—as well as the lack of comprehensive encoding systems along the lines of the notes, clefs, and bars of the Western musical tradition, has necessitated the functionally oral transmission of dance repertory for centuries. The constitution of history is always a leaky enterprise, but the lack of consistent notation has resulted in a dancerly canon palpably haunted by absent art and missing bodies. One could read what little remains of historical ballet repertory as a futile effort to hold on to prior art, to choreograph (the term itself is an ironic portmanteau of Greek and English words for dance writing) as a means to remember, to always only partially re-embody the systems, grammars, affects, and declensions of dances long lost but that still parameter contemporary movements. The repertory that falls out of history constitutes a sort of dancerly dark matter: choreographed gestures that are invisible and can be sensed only indirectly, but whose cultural gravity nonetheless warps contemporary understandings of what meanings can be generated by bodies in motion.

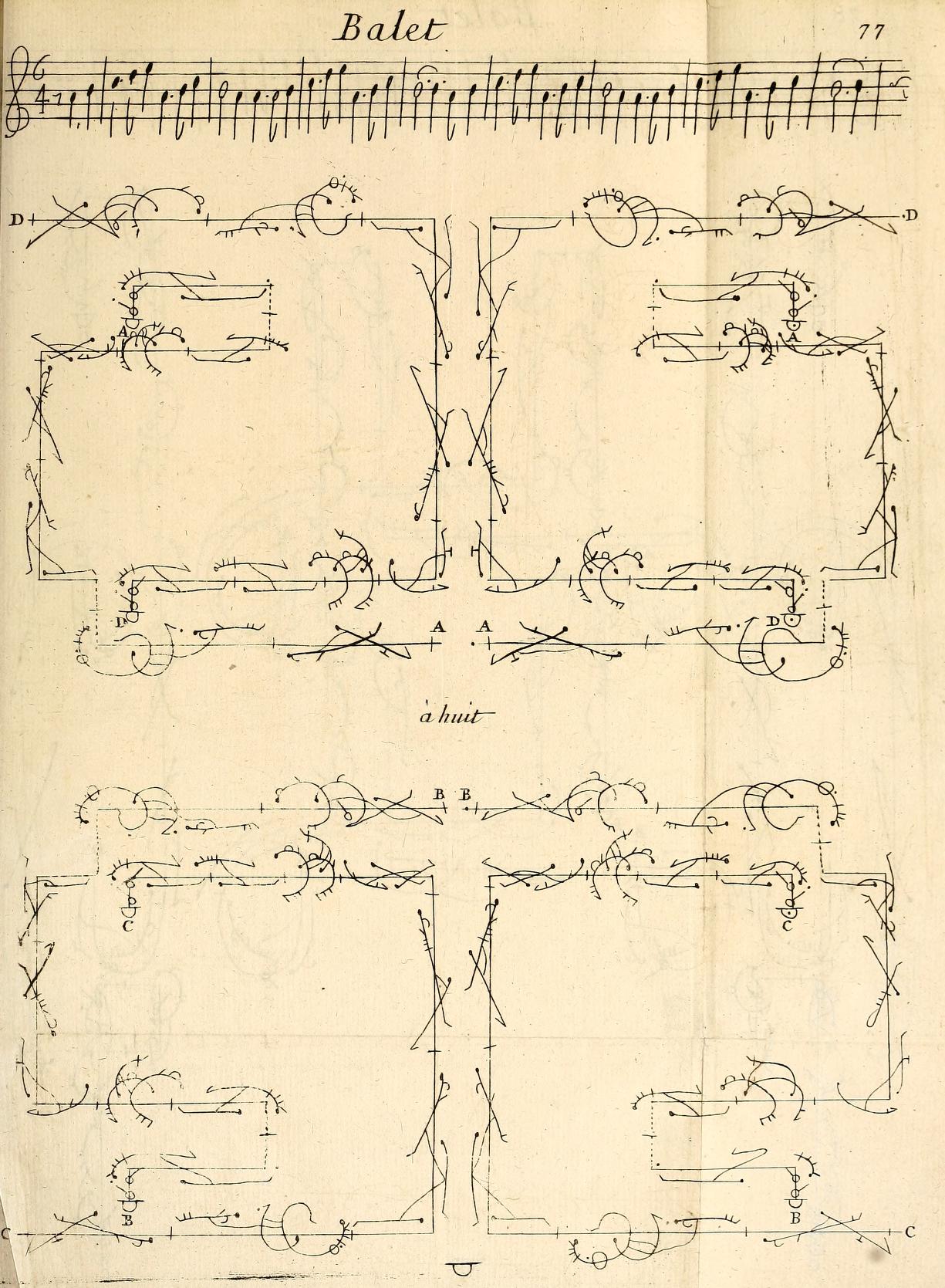

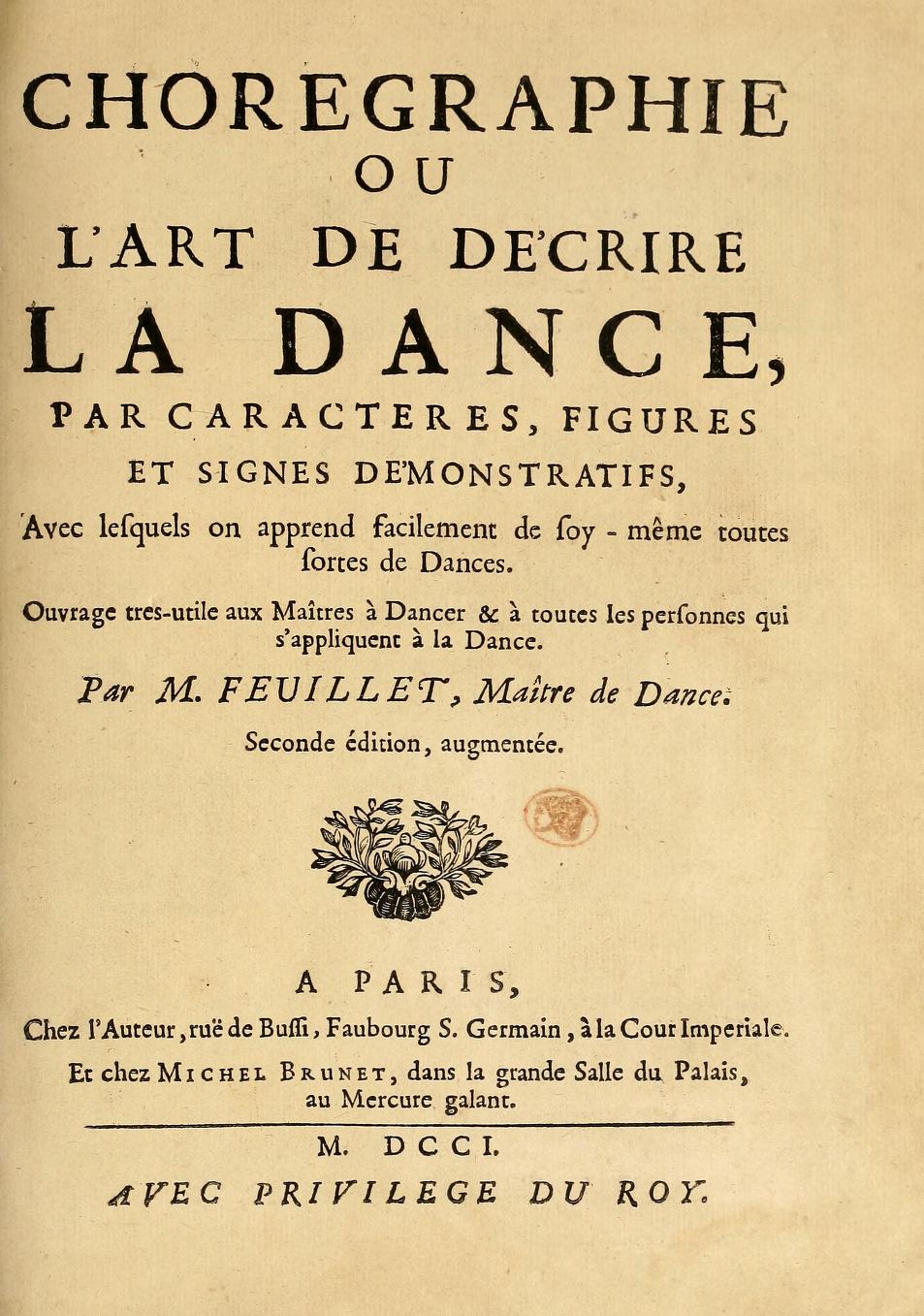

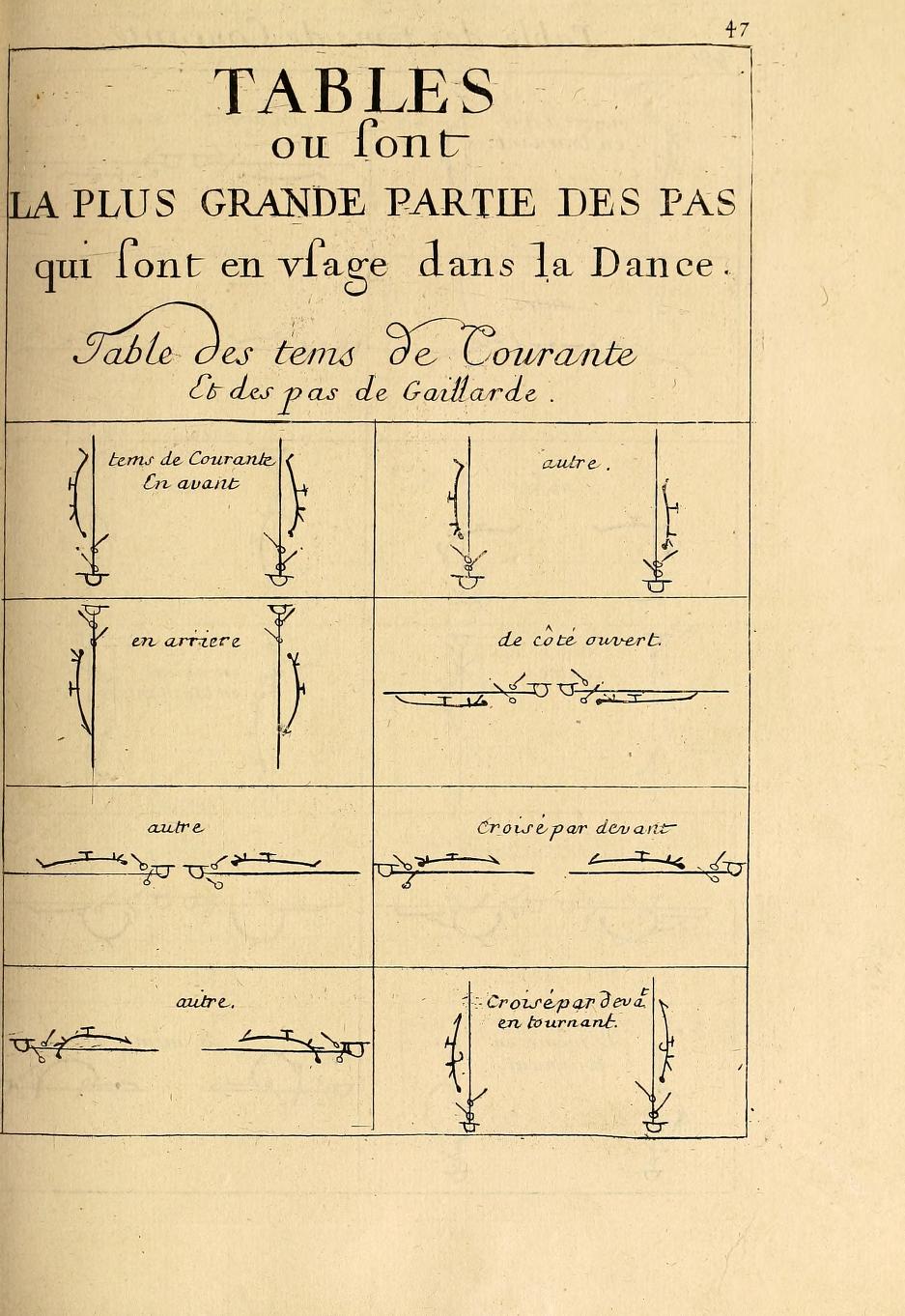

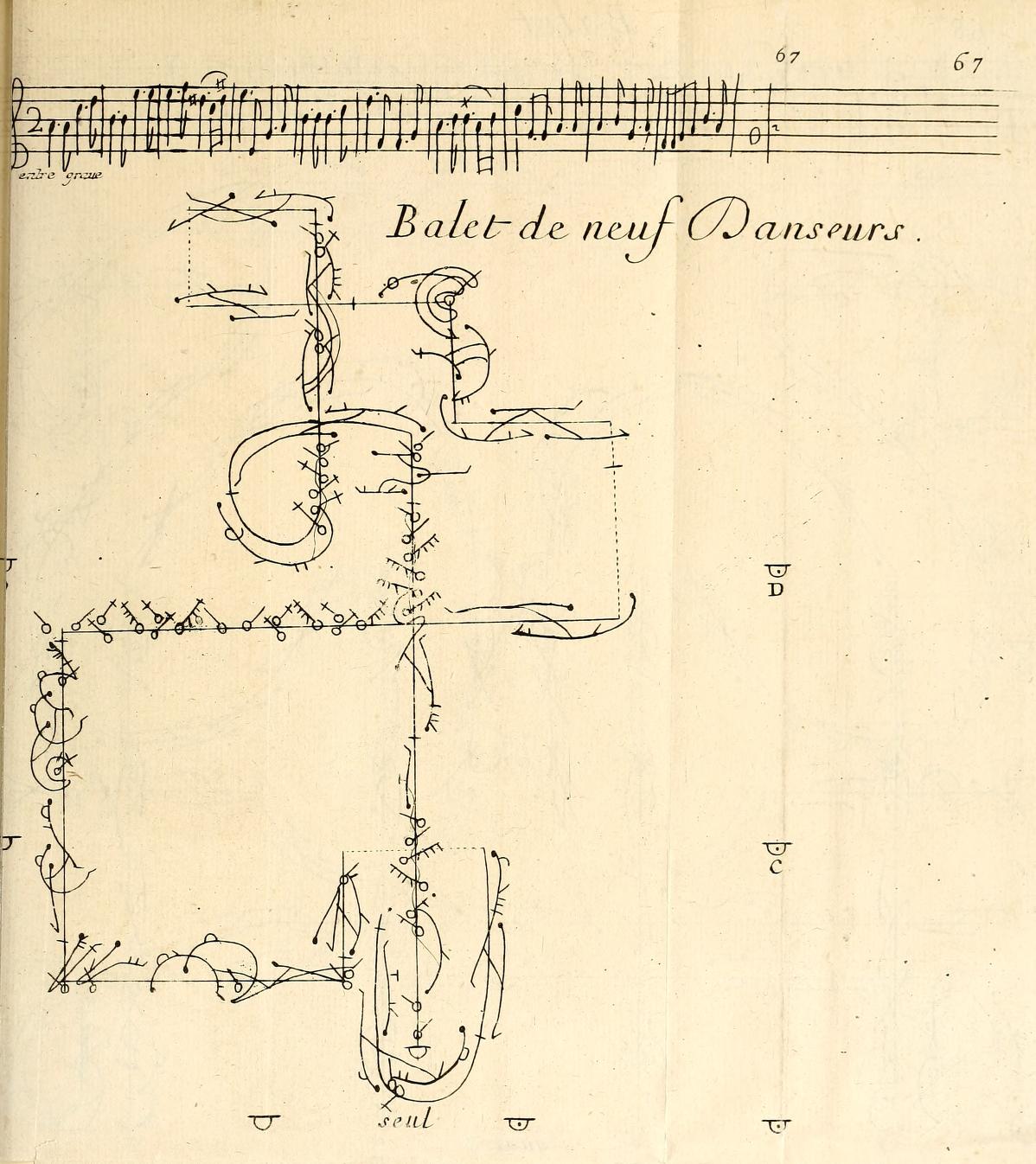

As such, I am inclined to teach dance history as a genealogy of technological failure, an archipelago of ambivalent innovations that inform how the dancing body is turned into code and transmitted through time. Shortly after ballet’s inception in 17th century France, Louis XIV realized the cultural and colonial imperative of exporting the balletic form, and commissioned what came to be known as Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, one of the first (and indeed, one of the few state-sanctioned) dance notation systems.

The method maintained relative popularity into the 18th century despite its complicated schematic nature and limited set of symbols. In the mid-20th century, Rudolph Laban (followed by Ann Hutchinson Guest, among others) composed and elaborated the most contemporarily prevalent notation system, Labanotation.

It is still in use, but as exacting as the system is, performative affect tends to fall out of encoding, and it is correspondingly time consuming to deploy. In the 1999 Pillow footage, Kaiser quotes Cunningham, “Only when dance notation [is] truly visual [will] it actually become a useful tool for dancers and choreographers.” This sentiment is apropos the last 400 or so years of the Western dance tradition, as the overwhelming majority of dances are not documented, are rarely re-viewed or re-constructed, and if they are subjected to historical analysis it is through the decidedly indirect aperture of journalistic reviews and anecdotal reports.

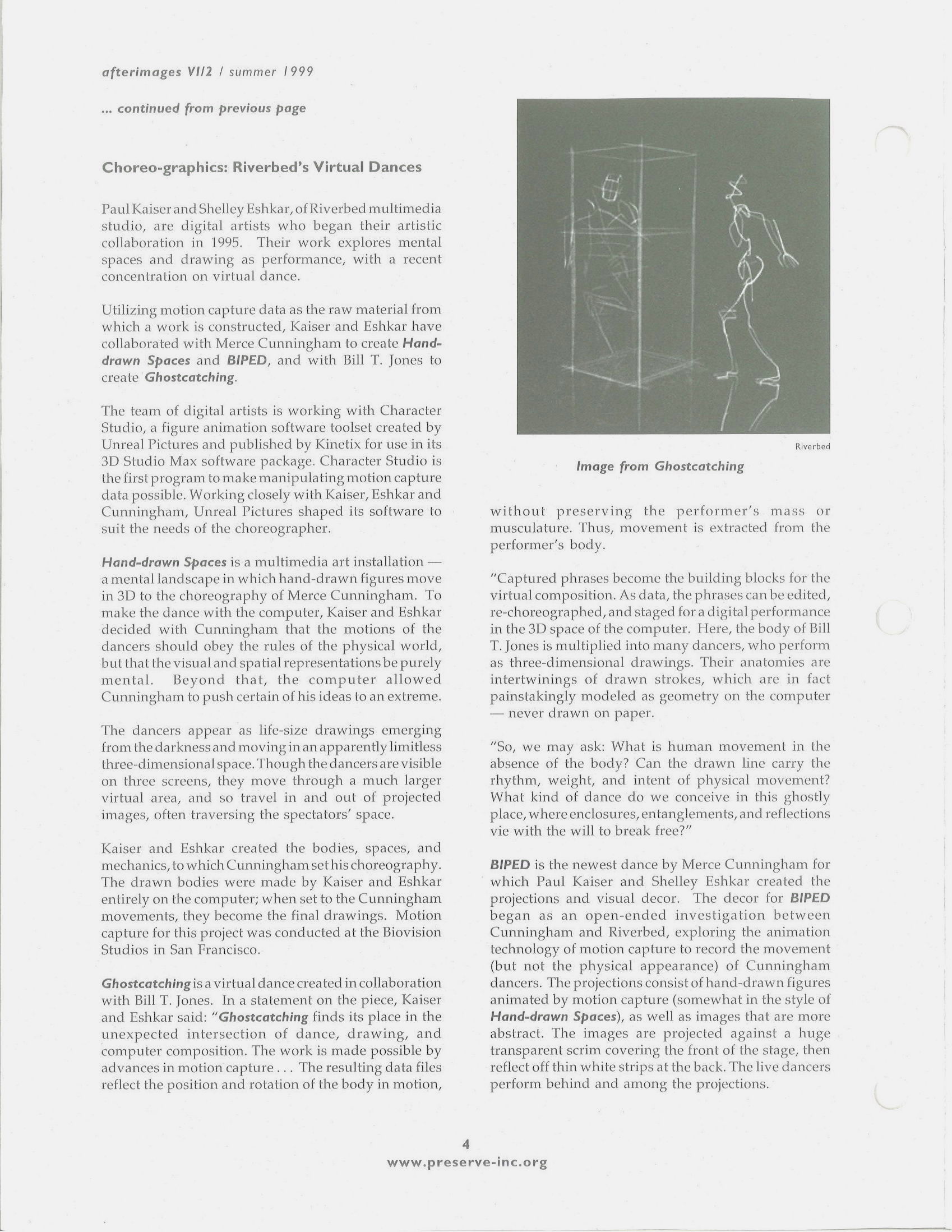

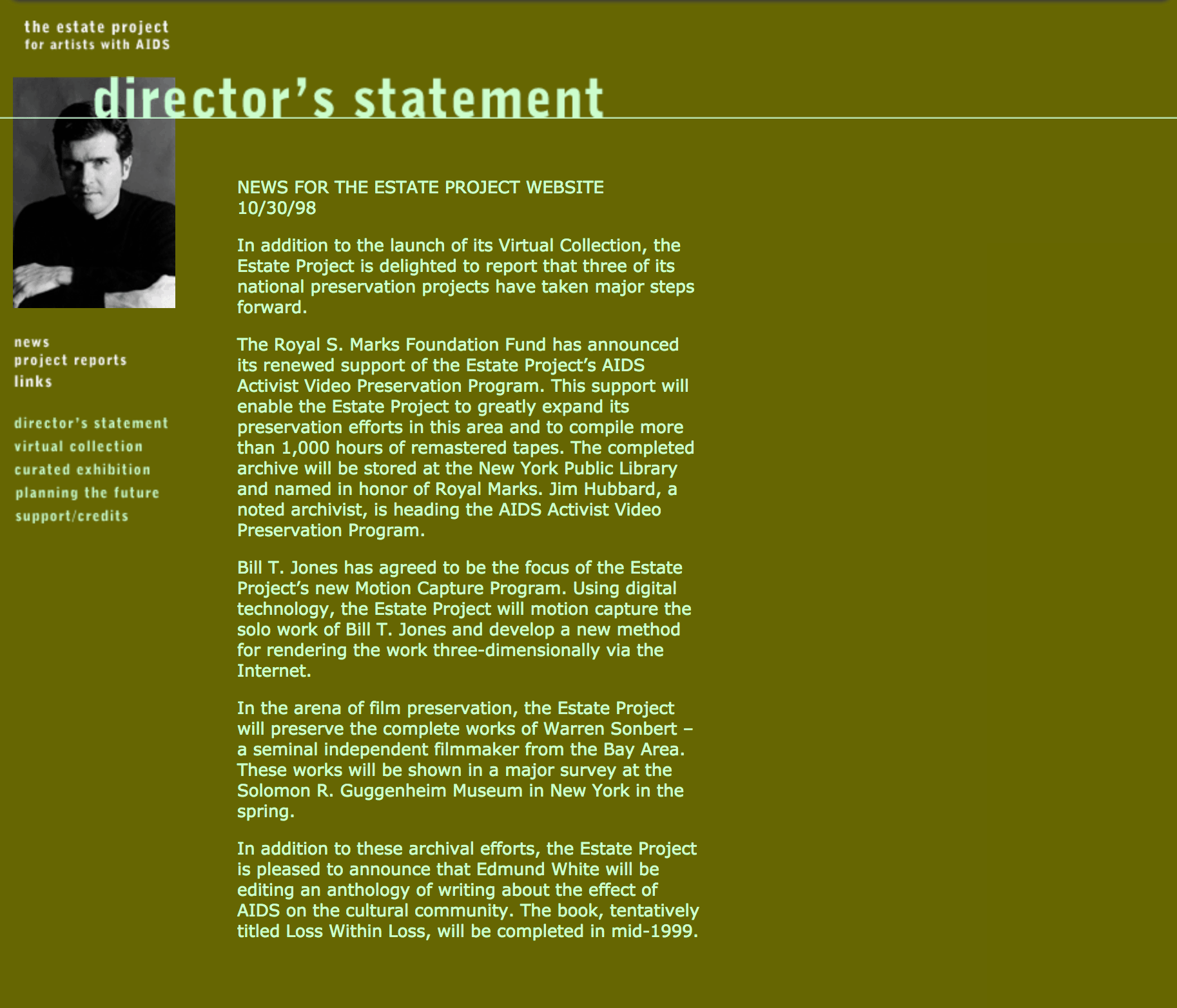

Some bodies are more forcefully absented from the official record than others, and the Estate Project’s preservation efforts sought to document work made particularly vulnerable by the time horizon HIV/AIDS imposed on the bodies of affected dancers and choreographers. By 1999, Moore had already marshaled several years of grant monies to attempt an intervention in the disappearance of such dances. The Project’s internal budget reports (now held in the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division of the New York Public Library) document the allocation of funds for a trial use of Labanotation to preserve several dances, though the eventual move to motion capture indicates these trials were unsatisfactory. With the aim of creating “museums of dance,” Moore received funding to conduct motion capture experiments with Kaiser and Eshkar. The hope was that mocap might be the technology of visual notation that Cunningham had presupposed. Interested in the technical and aesthetic challenges afforded by capturing differing styles of movement, the group recorded Megan Pepin (then a student at the School of American Ballet) performing a solo from Balanchine’s Harlequinade, and as well as improvisations by choreographer Bill T. Jones. The resulting footage was presented at the 1999 Pillow panel, animated biometric data notably lacking markers of gender, sexuality and race.

The artists’ bodily movements were indeed successfully captured, but at the cost of their qualities. Such erasure of bodily difference seems in tense relation to the test’s intended function: to enable a preservation project grounded in physical and sexual specificity.

The Written Record

Little has been written about these efforts. Ann Dils’s essay “Absent/Presence” is a notable exception. In it, she mentions the Estate Project initiative in the context of Kaiser, Eshkar, and Jones’s 1999 collaboration, Ghostcatching (a motion-capture-enabled media work that Jacob’s Pillow co-produced at MASS MoCA) and an electronic letter Moore wrote for The Estate Project’s then website, ArtistsWithAIDS.org.

The site has been offline for years, but by consulting the Internet Archive’s “Wayback Machine” I was able to view the text approximately as Dils had: “Bill T. Jones has agreed to be the focus of the Estate Project’s new Motion Capture Program. Using digital technology, the Estate Project will motion capture the solo work of Bill T. Jones and develop a new method for rendering the work three-dimensionally via the Internet.” I also located a limited release publication called afterimages (Preserve, Inc.’s “newsletter of performing arts documentation and preservation,” printed in collaboration with the Pillow and consulted on by Moore) that went further, suggesting the mocap program might result in novel choreographic methods for artists to continue working despite being “physically limited by age or illness, such as HIV.”

The dream was for motion capture to simultaneously preserve at-risk repertory and expand the ways, means, and potentialities of choreographic practice.

To my knowledge, nothing more was written on the subject in The Estate Project’s external communications, and the initiative (and, for that matter, the Estate Project itself) soon folded. The technology was just too unwieldy, too expensive, and both Kaiser and Moore (in recent interviews) alluded to technophobic tendencies in the dance world that precluded further testing. It couldn’t have helped that the motion capture rigs just weren’t very accurate. In an aside during the 1999 panel, Eshkar says revealingly of Jones, “The machine could barely snare him,” and both Jones and Kaiser recall motion capture markers flying off during Ghostcatching recording sessions, the result of Jones’ sweating body being literally too slippery to be caught by the apparatus.

Conclusion

The Estate Project’s dance preservation efforts may have been archival failures, but the work forms part of a larger, queer, cultural history of the Internet. Michael Girard, a computer scientist collaborator of Shelley and Eshkar, told me in a recent interview that “the soul of motion capture… started in those pioneering days back with Bill T. Jones standing naked… everything expands from that exciting moment.” Girard is considered one of the architects of contemporary motion capture software and developed a (now classic) bipedal skeletal physics software plugin called “Biped,” after which Cunningham named his Biped.

One of the “Biped” sample source files was called “Toddler with Diaper,” (though it is more popularly known as “Baby Cha-Cha”) and was arguably the first Internet meme. The codebase Girard created for “Biped” (as well as Biped and Ghostcatching) was eventually incorporated into animation software called 3DS MAX, contemporarily distributed by software giant, Autodesk. Motion capture has since become ubiquitous, with films like The Lord of the Rings and music videos by artists such as Justin Timberlake relying on software like “Biped” more than ever.

Technologies of motion capture may not be dance notation in the traditional sense, but both exist to transform bodily movements into data through an algorithmic apparatus. Laban, Beauchamp-Feuillet, et al, require humans to execute sequences of encoding and decoding, transmogrifying bodies into statistics and back again. By contrast, thanks to folks like Girard and the endeavors of Kaiser, Eshkar, Jones, Cunningham, and Moore, motion capture and animation software now comes preloaded with skeletal, muscular, facial, and movement models derived from decades of prior art and data collection. This expansive archive may not be accessible in ways to which we’re accustomed, but it’s in there, shaping the physics and aesthetics of all resulting media. In such cases, live bodies are no longer necessary to choreograph, and online dances made without dancers are increasingly common. The code that powers this creativity is parameterized by live bodies long gone, the resulting software inhabited—perhaps haunted—by the biodata and movements of the captured. Ghosts dance on in the code, leaving ambiguous who, at any moment, is choreographing on whom.

PUBLISHED November 2018