“What you doin' on your back, aah

What you doin' on your back, aah?

You should be dancing, yeah

Dancing, yeah”

Anxieties, Gendered, Dancerly and Otherwise

The western tradition has long been suspicious of the male dancer. Men have been variously considered too grotesque, too unsightly, and too queer for the stage, pervading lazy stereotypes that have lasted for centuries. As dramatist Théophile Gautier wrote in 1838, “Nothing is more distasteful than a man who shows his red neck, his big muscular arms, his legs with the calves of a parish beadle, and all his strong massive frame shaken by leaps and pirouettes.” Such squeamishness around male dancers is hardly limited to ballet history however, and any number of popular television shows (Community, Glee, Crazy Ex Girlfriend) and films (Magic Mike, Saturday Night Fever) have narratives centering on the contradictory mores and expectations of men who dance. Dance has always been a useful art to stage tricky representational issues, and to discuss the “trouble of the male dancer” (as theorist Ramsay Burt helpfully describes it in the context of Gautier) is to explore how gender is kinesthetically understood, taught, and expressed.

For a problem set so proliferated in popular culture, the tense relationship between the male dancer and their dancing finds infrequent performance in live art. The balletic canon deals obliquely with the multiple, simultaneous expectations imposed on male dancers, with a spectrum of masculine gender expression that ranges from ubermenchish pirates in Le Corsaire to travesti witches in La Sylphide to tragically effeminate puppets in Petrouchka. Contemporary choreographies stage the construction and constructedness of masculinity more frequently—Pina Bausch’s oeuvre and John Neumeier’s Nijinsky come to mind—but dances that take dancerly gender trouble as their stated subject are rare.

About “I Want to Dance Better At Parties”

This context makes Gideon Obarzanek’s I Want to Dance Better at Parties all the more historically singular. It is a dance about men learning how to dance, and consideration of male dancerly ambivalence in public space makes up the work’s awkward heart.

The piece was created on Obarzanek’s then company, Chunky Move, and originates in a tragic personal narrative: Obarzanek interviewed a widower, Phillip Rose, whose process of grieving was unexpectedly eased by learning ballroom dance. Rose’s story is scaffolded by shame and conflicting attitudes towards his own desires: he wants badly to dance well, but learning is stultifying, especially given grief for want of a (life) partner. Rose’s recorded voice accompanies the work, interspersed with the confessional narratives of four additional men who discuss their experiences of dancing socially. I Want to Dance Better at Parties, is, literally, about dancing at parties, but particular about the interpersonal conventions of social dancing, and the awkwardness of not dancing well. It is a concert dance about social dance, a transposition of five interview subjects’ reminiscences about dance rendered as dance theater that explores men’s fears for what their movements might reveal or misrepresent.

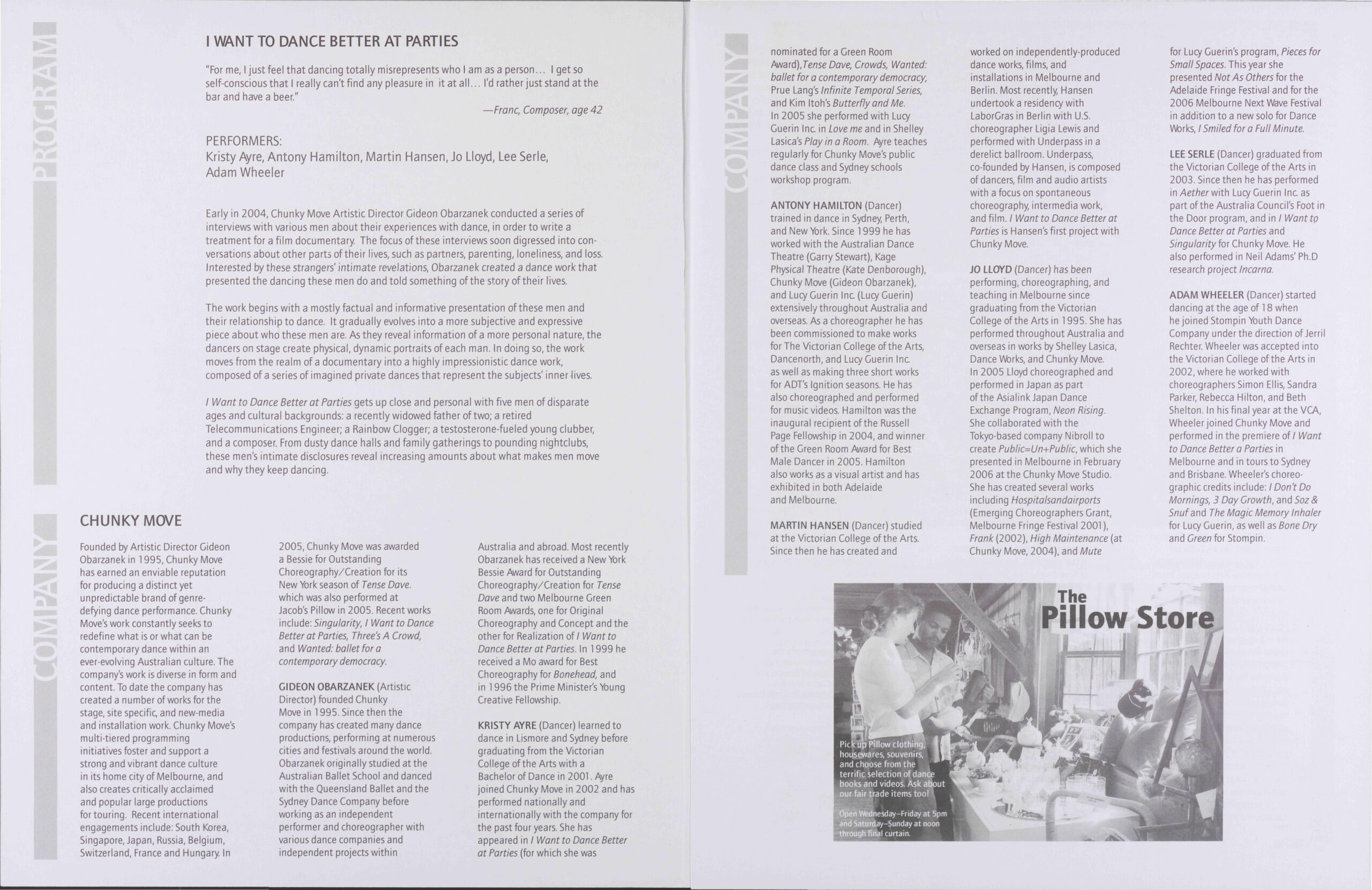

The work begins with a woman walking into a narrow rectangle of stage light. She is accompanied by the image of a man projected onto a flat panel suspended from the ceiling, just above and behind her. These two figures—the live dancer and her digital double—begin a percussive line dance, thumbs in their jeans and movement constrained to their light boxes. Their movements and affects closely resemble each other, and it’s clear that they are dancing an identical choreographic sequence, an uncanny duet somewhere between the live and the virtually real. Unexpectedly, in the middle of their movements together, the projected dancer stops suddenly, digitally frozen in space and time, as the live dancer continues their sequence. Their duet is oddly disrupted, and it is initially unclear if something went wrong—a glitch with the projector?—until exactly 16 counts later when the projected dancer seamlessly rejoins the dance. The awkward lapse is revealed to be a theatrical device that highlights the oddity—and precarity—of the man and woman’s dance together.

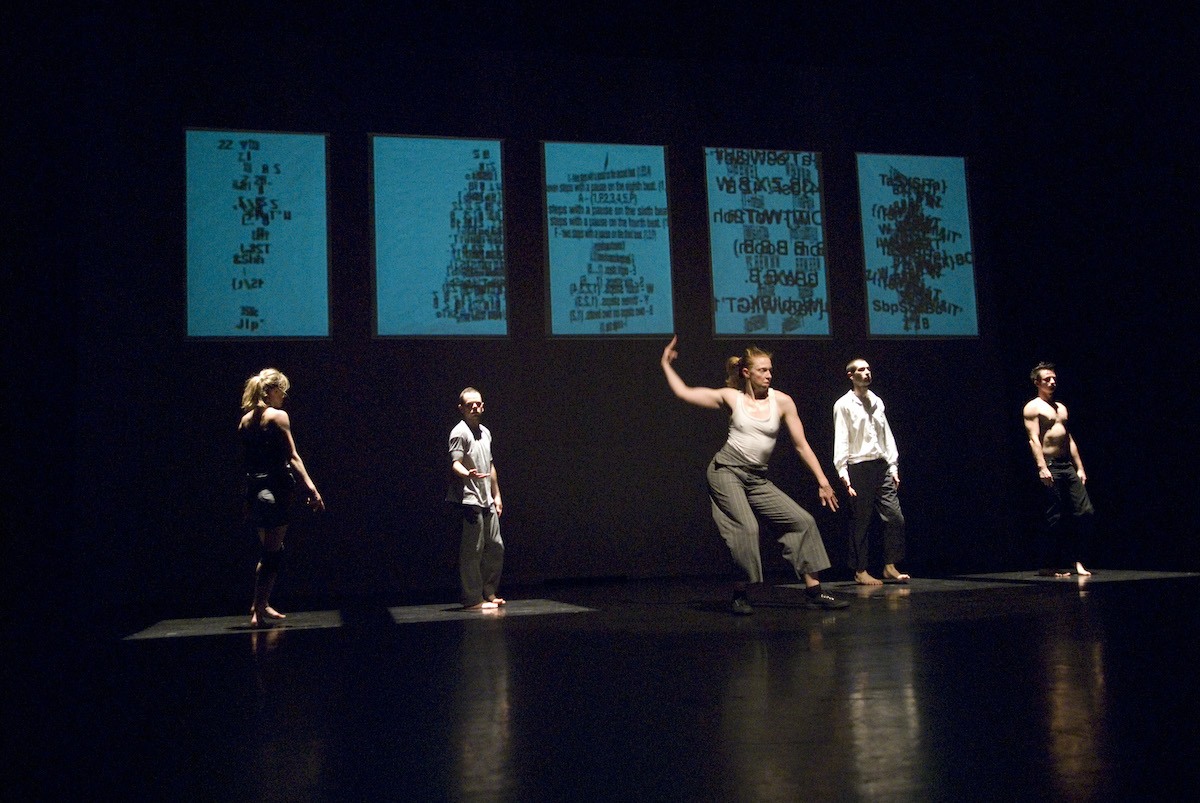

Three other live dancers gradually appear on stage accompanied by projections that dance alongside them. There are four distinct duets between real and virtual dancers, each a casual, flowing social dance accompanied by music ranging from a club remix of “Mambo Italiano” to Keith Urban’s “Somebody Like You.” The dancers perform effortlessly and with confidence, baselining apparently shared social choreographic conventions. This is a dance club where everyone seems quite comfortable being a member.

The appearance of a fifth dancer dyad disrupts the order of things. Instead of being accompanied by club music, there’s a loud, static tone, and the new pair of dancers are still, awkwardly looking out towards the audience. It’s a rupture in the order of things, and the other occupants of the stage take notice. The digital figures look towards the non-conforming digital performer, then walk out of their respective frames in a manner that suggests a response to the stage action, and that they could easily return if so inclined. The live dancers similarly shift their focus onto the odd non-dancer and congregate in a tight clump around him. The stage lighting shifts, and the reluctant dancer (Lee Serle) continues to face the audience while the others gyrate to a Muzak rendition of the disco anthem, “Stayin’ Alive,” pitting Serle’s consternation and muted moroseness against an inferred image of John Travolta’s dancerly triumphs from the film Saturday Night Fever. Meanwhile, a man’s recorded voice describes disinterest in dancing and his desire to avoid it “at all costs.”

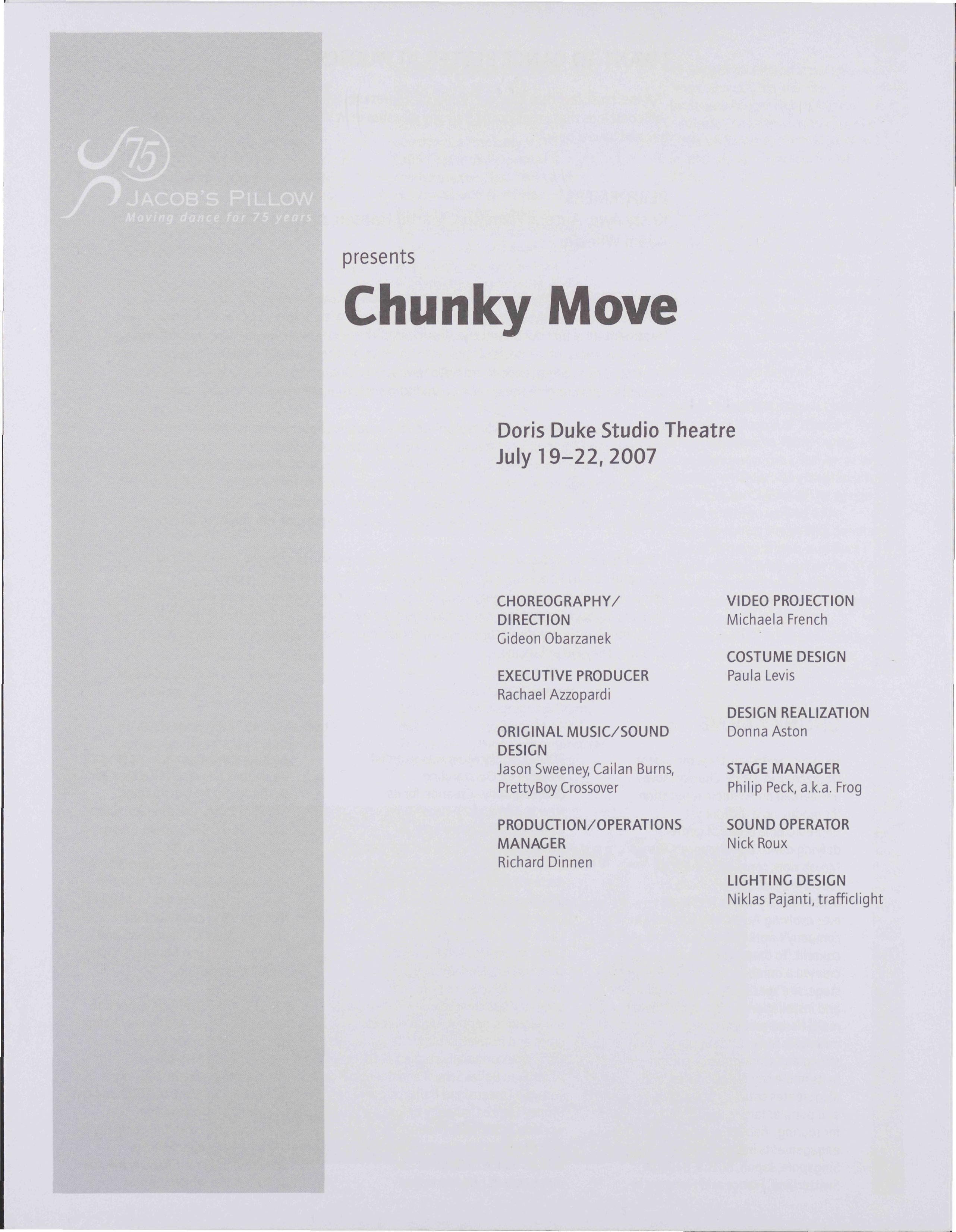

As though to synesthetically ascribe color to the ambivalent emotional state depicted by the performers, the stage scrim is lit in a deep, coagulated red, a Rothko-esque saturated field interspersed with the five rectangular projection surfaces. The dancers, now backlit, move to the sounds of 16-bit disco while a man’s doughy face (Rose) is projected onto the stage. He appears to watch the goings-on without particular affect, his pallid neutrality a massively expanded mirror of Serle’s earlier internalized panic. This juxtaposition of forced facial neutrality alongside recorded personal narratives of shame and awkwardness situates the onstage performance as reenactments colored by heightened emotionality. The other dancers then effortlessly move through a series of abstracted line dances while Serle, in a pedestrian mode, reverts to a sequence of coping strategies to get through the awkwardness. He stares, drinks a beer, sits, crosses his legs, tinkers with a flip phone, rolls a cigarette, and walks offstage as the Rose audio describes the feeling that “others are judging me.”

I Want to Dance Better at Parties is filled with many such dense, associative scenes, constellating affective states ranging from anxious dread to awkward obligation. Later in the work (set against a monologue describing a man’s reluctance to dance because the “faces all [seem] like they’re staring”), Serle again stands to face the audience, shrugging his shoulders to his ears in a contorted posture of uncertainty. Other onstage dancers execute a liquid, silky phrase while a woman, Jo Lloyd, gently places Serle’s hands on her swaying body as though to teach him how to partner dance. In response, Serle widens his eyes and puffs his cheeks, a micro-facial expression of gross fear writ large. The grotesqueness of the scene increases: Serle bends up his nose with a finger and palms his crotch, further uglying up his masculinity in opposition to the Travoltaian disco ideal. Lloyd—seemingly unperturbed by Serle’s bizarre behavior—gently removes his hands from face and crotch and places them on her hips. The distended face, however, remains until the end of the episode.

Perhaps there is a touch of irony in the choreographing of amateurish awkwardness onto professional dancers. In I Want to Dance Better at Parties the performers vacillate between monstrously physical, abstract movement phrases (executed with abandon and obvious skill) and such claustrophobic scenes of gendered panic as the above. Indeed, much of the theatrical tension of the work results from uncertainty as to when (or on whom) an awkward scene will play out.

The Closing Party

At the conclusion of their performance run, Jacob’s Pillow threw a party for the cast of I Want to Dance Better at Parties. The proceedings were recorded, and documentation of the evening resides in the Pillow Archives, along with video of virtually every other party thrown at the Pillow over the last twenty years. The best dancers in the world can be found in this awkward archive, not in their onstage element but in its aftermath, socializing, consuming wine and cheese, and dancing dorkily with one another. These videos of dancers dancing at parties aren’t intended to be watched by anyone in particular, but the fact of their existence means that anyone who ever attended a Pillow party can be reasonably assured their experience was surreptitiously captured. Indeed, I’m confident that somewhere in the Pillow archive there is footage of a younger me, dancing terribly. Still, having reviewed their performances both on and offstage, I don’t think the cast of I Want to Dance Better at Parties need worry. At the party thrown in their honor, nobody danced better or more confidently than they did.