I am the genre."

Graduate School and Difficult Truths

While considering graduate schools in choreography, I visited the Dance Department at the New York University Tisch School of the Arts. Such tours are scripted affairs where potential students are guided along predetermined tracks, like Disney World, only in the long run more expensive. Current students are positioned at regular intervals and encouraged by faculty to emphasize their positive experiences. Meanwhile, the hopeful enrollees navigate a Potemkin department lubricated by frictionless assurances that a bogglingly costly terminal degree in an art form that arguably peaked in the mid-1900s is a good life choice. During my Tisch tour I lost my group in favor of popping into the student lounge, where I asked the occupying students if going to Tisch was worth it. My question was met by a 20-something year old Kyle Abraham, then completing his graduate studies. He told me with the respect, kindness, and candor that I have come to love in the man, that my going to NYU was almost certainly an irredeemably terrible idea.

I remember this exchange for what it reveals about Abraham’s unwillingness to tell dopey falsehoods. He, in that moment, chose to communicate a difficult choreographic truth that I wasn’t ready to hear. (Long story short, my MFA is from NYU.) Considering the episode in the context of Abraham’s long career, it seems the man has become extremely successful for his unwillingness to bend to the comfort of the easy answer. His oeuvre is populated with uncomfortable truths, messages his audience may or may not be willing or able to absorb. As Abraham left NYU I was working as a Producer for DanceNOW[NYC], and in 2006 we presented a solo of his titled Inventing Pookie Jenkins. The piece was a breakout moment for Abraham, who went on to perform the work at Jacob’s Pillow in 2010. The dance is dense, weighty with pastiched complexity, and serves as a prescient gesture of the kinetic contradictions Abraham has explored throughout his accoladed life in dance.

Inventing Pookie Jenkins

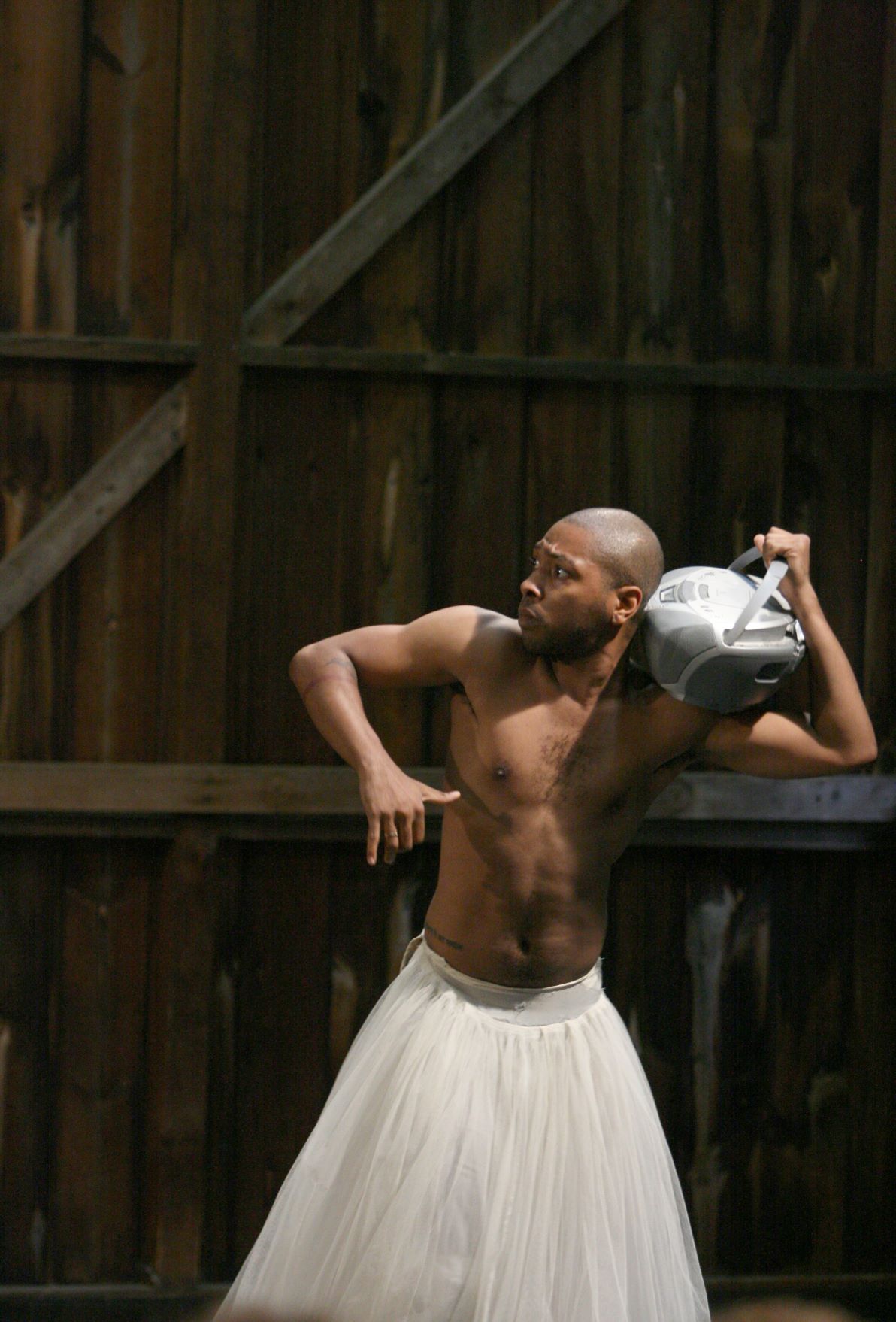

The excerpt begins with Abraham in a warm, downcast spotlight, shirtless, his undulating torso accentuated by a bright white, floor-length, tulle skirt. A simple costume element evocative of a stereotypical balletic tutu, the item’s apparent feminine signifying is in forceful contrast to Abraham’s masculine embodiment. There’s a color scheme at work as well: Abraham is a Black man with dark, plentiful tattoos, and the white blankness of the tutu forms a chiaroscuro contrast across a spectrum of masculine and feminine tropes, as well as a racially marked body partially concealed by a prototypically, historically, and literally white skirt.

The contrasts continue at the level of the movement vocabulary. The first moments of the solo excerpt encompass a heterodox amalgam of classical, postmodern, and club dance movements. At the start, Abraham waves one hand, then two, accompanied by the basso and opening plinks of Dizzee Rascal’s rap track, “Respect Me.” His hands then scrape curvilinear arcs above his head and in front of his torso, a kinespheric exploration reminiscent of William Forsythe’s improvisations on a theme of Laban. The sequence is repeated with permutations and quickening tempo, momentarily situating the gestures in the universe of the club, until with preternatural suddenness Abraham’s body is sucked down to the floor with hands braided gently over a foot and bended knee, a motif seemingly referring to ballet choreographer Michel Fokine’s infamous paean to the tragic feminine and romantic queerness, The Dying Swan.

The music is a useful guide to the complexities of the scene. Critics of Pookie in its early phases seemed disconcerted by Dizzee Rascal’s grime rap as accompanying score, with the Village Voice’s dance critic describing the accompanying track as “gangland tirades.” This reductive sentiment is unearned, and there is a lot sonically going on. “Respect Me” is a track from Rascal’s 2004 album, aptly named “Showtime,” with top notes of a digitally-processed, bamboo-flute-meets-Nintendo plink and underlying textures of a dubstep bass line. The lyrics are a study in contrasts complementary to those scenically fostered by Abraham’s choreography, ruminating on audience reception and violence (I’m going to make you respect me if it kills you) as well as questioning of the relationship between the artist’s stage persona and personal agency (If I don’t speak, who’s going to speak for me?).

The complexity of Abraham’s movement vocabulary expands as the solo edges on, virtuosically rendered on his able body. The seamless transitions between vocabularies is notable, with flawless accent and invisible segues between movement phrases, a choreographic code switching between raced, gendered, ballet historical and contemporary movements. The work is triply virtuosic: for its dense composition, its exceptional execution, and for its polyvalence which vitally complicates seemingly stable distinctions between dances for “street” and “stage.”

At around 0:50 of the above excerpt, Abraham transitions from a sequence of pugilistic nose thumbing back to “dying swan,” but unlike previous iterations, he remains there, if for a moment, in his avian pose. There is a cascading wave of energy that originates from his pelvis and reverberates through his spine, ripplingly bobbing through his arms and hands, re-energizing and reinforcing the watery, femme energy of the posture. But then, with staccato impulse, he thrusts his hands forward, a glitch in the ballet matrix, before returning to postmodern vocabularies. Abraham here evidences the lack of stability of these movement techniques, demonstrating how, through the medium of his capable personage, dance movements are always on the verge of overriding and becoming one another.

Recent Movements

After premiering Pookie, Abraham’s career took off, and he has since won most of the awards for choreographic excellence that exist. A bit over a decade later, it was announced that Abraham was to be the first African American choreographer in over a decade to create a new work on the New York City Ballet (NYCB). NYCB’s interim management (interim, because they had just removed their longtime director, Peter Martins) had selected Abraham, and the stakes of the selection were neither subtle nor lost on him. In an interview with The New Yorker, Abraham noted that, “I think some people will come to this with the expectation that I’m going to make a hip-hop dance, because I’m a black choreographer.” Similarly, in an interview with The New York Times, he states categorically that he’s not there to contribute “urban zhoozh.” Abraham seemed clearly in a position—not unfamiliar to successful folks of color—where by dint of working in an industry typically reserved for white folks, the success or failure of his labors would not only comment on his individual qualities but also, apparently, act as a litmus test for all the artists of color that NYCB had failed to equitably engage over the years.

The resulting work was titled The Runaway. It featured soloist Taylor Stanley, with his silky epaulement and arabesque, dancing two solos to neo-classicist Nico Muhly and rapper Kanye West. With The Runaway as with Inventing Pookie Jenkins, the language and trappings of classical ballet are adroitly juxtaposed with other vocabularies, which Stanley ably throws down. NYCB put out an excerpt of the dance that features a moment where, after a series of impeccably balanced ronds-de-jambe, Stanley throws in a popular social dance move, homage to Jay-Z and latter-day Fortnite meme, “the brush,” where he queerly wipes dirt off his shoulders. The audience laughs. The juxtaposition is funny, principally if one is viewing the dance with the understanding that such moves (coded as Black, effeminate, queer) are not proper in the context of NYCB in the Koch Theater. It’s funny because one of the things is not like the others.

Abraham, of course, has been playing with the aesthetic contrasts of unbelonging since at least 2009. Considered within the national conversation on race and the still largely-segregated balletic milieu, it seems that it’s the American ballet world that operates incongruously and out of place with our contemporary dance moment, not Abraham. I spoke with him by phone about his career and plans. He’s starting a series of pieces that will usher his creative process into the next decade. Dances that, echoing bell hooks, celebrate “the unseen” and make dancespace for the subject of Black love.