I’m always fascinated... by [those] trying to get robots to be human. Why don’t we get humans to get more robotic?

Dancers and Robots

Mechanical contrivances and robots that look and move like humans have caused considerable anxiety throughout recorded history. When objects without life are animated and appear human, the seemingly stable specialness of humanity is troubled: if inert objects can gain life, does that mean humans are alive, or only seemingly so? What are the conditions through which objects become real or perform as lifelike, and how can we distinguish between human-seeming automata and “real” people?

Such destabilizing questions have been explored by generations of writers, poets, artists and futurists. Consider the myth of Pygmalion, who, per Ovid, made an ivory statue so realistic he fell in love with it, or the story of Pinocchio, who, per the originating Collodi stories, was a puppet cursed with self-awareness and the ambition to become real. Capacity for movement features prominently in this literature, and science fiction films depict character choreographies and dances as tests of fealty and realness, often anticipating violence and sex. Consider the lascivious, synchronized movements of the “fembots” in Austin Powers and the title character’s deployment of a “sexy” dance that literally blows their minds. Or, consider the character “Zhora Salome,” a runaway android in Blade Runner named for the New Testament Salome (whose dancing was instrumental in the death of St. John) and whose feminist agency inspired choreographer Loïe Fuller. Zhora the robot avoids detection from human authorities by working as an exotic dancer, and an early version of Blade Runner even featured a (rehearsed but never filmed) Fuller-esque serpentine dance, to be performed with an edenic, seemingly-alive-but-actually-a-robot snake.

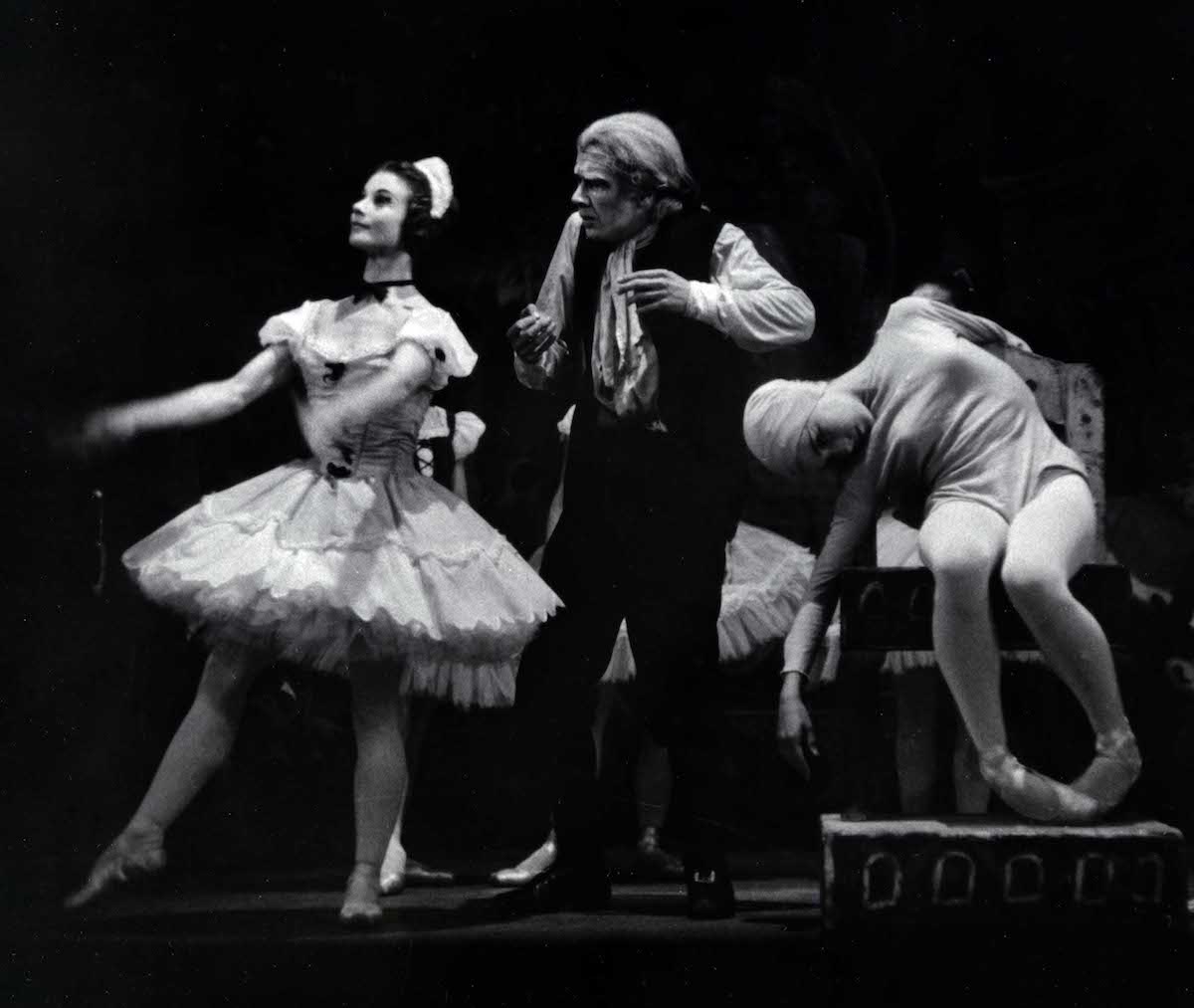

Western dance history brims with ambivalent stories about automata and their relationships with humans. Consider Coppélia, (originally subtitled, “The Girl with the Enamel Eyes”) about a lifelike doll and a man who falls in love with it.

In 2019, the ballet was remade by choreographer Chase Brock as The Girl with the Alkaline Eyes, with additional thematics lifted from the TV show Black Mirror and the science fiction film, Ex Machina. There’s also Petrouchka, which features a gaggle of haunting puppets animated, à la “Yo Gabba Gabba,” by a nefarious sorcerer. This ballet was memorably performed by actual puppets in Basil Twist’s production, seen at the Pillow in 2002.

And then, most popularly, is The Nutcracker, a racial cavalcade about a mechanical nutcracker that is, because of avuncular magic, also a handsome and eligible prince. How robots are made to seem and move like humans has been the subject of great creative exertion. Less frequently, however, is the inverse explored: how humans are made to perform more like robots.

I, John Heginbotham

In this regard, the choreography of John Heginbotham is unexpectedly instructive. In 2010, I was one of the producers for Heginbotham’s first solo show: a quartet semi-jokingly titled “One Man Show.” It was a depressive, dark cloud of a cabaret piece described by New York Times critic Roslyn Sulcas as “amateurish meandering.” (Thanks to the critical response of this early work, Heginbotham is now one of the top Google search results for the phrase, “weakly comic bad dance.”) Undeterred by this initial critical foible, Heginbotham continued making work over the subsequent decade, and since completing an accoladed tenure at the Mark Morris Dance Group has gone on to choreograph works for prestigious stages around the world. His dances have some things in common with his former boss—a shared sense of meticulousness, craft, and deep musicality—but where Morris’s works are frequently underwritten by a verging utopianism of community and visual harmony, Heginbotham frequently features dancers moving with virtuosic similitude and mechanistic quality. He easily makes the most robotic dances of any humanist I know.

Three months after “One Man Show,” Heginbotham premiered throwaway at the Dance Theater Workshop. It is a useful counterpoint to “One Man Show” in that it is short, hilarious, and free of sanctimonious pondering. The work is explicitly and implicitly about disposability, and deploys a stack of robotic referents to do so. Foremost, the dance is choreographed to “Technologic,” a clubby piece of danceable techno by the French, robot-imitating duo, Daft Punk. The music consists of dense, electrodisco percussion and an extensively digitally altered, robotic vocal line that issues some 300-odd commands having to do with technology (“Buy it, use it, break it, fix it, trash it, change it, mail, upgrade it…”) that act as a de facto choreographic score. Heginbotham’s dance features two performers (originally Maile Okamura and Brian Lawson, both Mark Morris alumni) engaged in an ironically combative gestural semaphore executed with intricate musicality and deadpan swishyness. The score, vocals, danced movements, and title situate the piece in an explicitly technologized arena: the choreography is scored by two humans with robot stage personas, while a robotic voice issues choreographic commands to two humans dancing robotically. throwaway is a dance about humans performing as robots.

Another Heginbotham duet that explores themes of duality, difference and roboticism is Twin, excerpted on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive, with music by, per the title, Aphex Twin, a famous techno influence on Daft Punk. In the clip below, we see Kristen Foote (a former Rockette accustomed to dancing as a cog within a dancerly machine) and Lindsey Jones (who works with the famously cerebral Pam Tanowitz and has performed for the Merce Cunningham Trust). Both are exceptional, of course, but they are also ridiculously smart dancers, capable of parsing—over the course of their storied careers—the most complex choreographic machinations of contemporary and historical repertory. Heginbotham puts these skills to good use in this excerpt, which consists of a minute and a half of nearly identical movement phrases, sometimes mirrored, sometimes with slightly divergent angling. The dancers move perfectly, like dazzle camouflage, leotard-clad machines, emulating each other and reproducing their choreographic commands.

And yet, while performing virtuosic sameness, the two dancers display a startling amount of base humanity. For example, at the close of the segment, Foote and Jones face the audience, pendularly swinging their left arms back and forth while shifting their gaze from one side of the stage to the other *while also* sticking their tongues out and flipping it across their face in the opposite direction of their eyes. It’s a nonsensical, Jabba the Hutt meets Kit-Cat Klock moment that brings to mind child’s play and computer code, in that both tend to be internally coherent and inordinately complex. Foote’s and Jones’s dancerly humanity is revealed through robotic gesture.

throwaway plays robotic performativity for laughs and Twin for virtuosic thrill, but both gesture to the fuzzy borders separating humans from robots acting like humans. Such dances are a means to explore the squishy boundaries between a human “us” and a robotic “them,” choreographies of difference that reflect persistent porousness and humanistic negotiation. In a telephone interview I asked Heginbotham about the relationship of his dances to our technophilic zeitgeist and the humanity of his dancers. He pointed me to a 1970s-era comedic mime team, Shields and Yarnell, who had a sketch variety show frequently featuring the duo acting like robots acting like humans, and engaging (typically, failing) at the execution of mundane human tasks such as eating breakfast. Heginbotham explains, “The thing that is so hilarious and delightful [about Shields and Yarnell] is that you know they’re people… They’re behaving like automatons, but you know they’re people… If they were actually robots, I don’t think it would be that interesting. Because they’re people acting like robots that’s more interesting, because of their humanity.”

Applying Heginbothamy Logic

There’s a scene in the sci-fi film, Ex Machina, where an obligatorily nefarious genius, (a bro computer programmer named Nathan, deliciously played by Oscar Isaac) flips a switch that instantly adjusts the lights in his lair from recessed and cool to pulsating and Prada red, like a living-room sized Studio 54. Disco classic “Get Down Saturday Night” throbs into the scene, and Kyoko (a mute, hyper-femme android played by the Royal Ballet-trained Wayne McGregor favorite, Sonoya Mizuno) bobs, bounces, and fingerguns to the beat. Nathan joins her, and the two dance an uncanny postmodern disco, executed in seamless synchrony, momentarily erasing the just-moments-ago obvious distinction between human and android. (That the classically-trained Mizuno plays Kyoko suggests possible future analysis in the shared semiosis of humanoid robots—frequently feminized, mute, eroticized objects—and stereotypes of the ballerina.)

It’s a *super* weird scene, brusquely unlike the cool, claustrophobic quality of the rest of the film. For years, I’ve struggled to understand the directorial choice, and it is only in light of Heginbotham’s roboduets that the scene makes any sense to me. Nathan and Kyoko’s dance is executed without expressed affect, and their deadpan, squarely perfect execution closely resembles Twin and throwaway. The three dances, considered together, suggest that the stylized repetition of acts that compose human identity constitutes a choreographic code base, a data set that can be used to make the robotic appear more human and the human more robotic. As such, these dances anticipate a not far-off day where casual observers will be unable to fully distinguish between a performance of robotic selfhood and its opposite.