America demands masculinity more than art."

Father of American Dance

There is perhaps no person more closely associated with the topic of men in dance than Ted Shawn (1891-1972), one of the founders of a theatrical dance tradition in the United States. Shawn’s lifelong mission was to establish dance as a respectable profession for men, or in his words, “a legitimate medium for the creative male artist.”Shawn, Ted. “Dancing Originally Occupation Limited to Men Alone,” Boston Herald, May 17, 1936. His crusade began between 1915-1930, when he and his dancing partner Ruth St. Denis helmed Denishawn, the first modern dance school and company, a venture that established him as one of the first internationally acclaimed male dancers, or as Shawn later proclaimed, the “Father of American Dance.” The moniker stuck. Achieving and maintaining that status required that he contend with a pervasive societal perception that dancing was a woman’s pastime or a degenerate form of entertainment. To that end, he drew upon some of the most progressive scientific ideas—as well conservative dogma—about gender and sexuality in order to mount a robust “defense of the male dancer” through the press, from the pulpit, in the museum, and above all, at the theater, where he presented a broad range of dances that demonstrated his vision for men in theatrical art dance outside of ballet.

Shawn’s defense of the male dancer was largely a religious one, namely that men had an ethical, moral and sacred imperative to dance. Before Shawn devoted himself to dance, he had studied to become a Methodist minister at the University of Colorado and based on his theological studies, he surmised that dancing was originally part of the Christian liturgy until the Middle Ages, when ascetics condemned beauty and pleasure from Christian ceremony. To demonstrate the ways dancing might revitalize the modern liturgy, Shawn choreographed and performed an entire church service in dance, an experiment that drew both praise and dissent from critics and clergy alike. In the ensuing years, Shawn’s religious argument broadened to include all religions, helping him to frame the dancing profession as a type of secular vocation. In fact, he wrote an editorial for the Boston Herald on the topic, declaring, if not overstating, that “A study of the dancing primitive peoples and of the civilizations of the past proves beyond question that it was largely and sometimes exclusively, a man’s occupation.”Shawn, Ted. “Dancing Originally Occupation Limited to Men Alone,” Boston Herald, May 17, 1936.

In one of his first publications on the topic of men in dance, Shawn predicted that the future of dance belonged to the “the freed vigorous expression of the superman.”“Dancing for Men.” Physical Culture (July 1917): 14-17. Indeed, many of the signature roles he would go on to create included religious figures, charismatic leaders, and even gods. Among the most popular of Shawn’s religious dances were Invocation to the Thunderbird (1918), his version of a Native American medicine man’s rain dance and The Cosmic Dance of Siva, (1926) a theatrical rendition of the sacred postures, gestures, and rhythms associated with the Hindu “Lord of the Dance.”

Shawn performed the dance about the god’s powers of creation, preservation and destruction on a platform with a life-sized “ring of fire” and other symbols associated with Siva iconography. In the final section, Shawn ignites incense to create plumes of smoke, invoking Siva’s favorite dancing place, the burning ghats of the Ganges, the site of ceremonial cremation.

In addition to aligning dancing for men as a form of religious expression, Shawn explored dancing as a martial art, especially in the years following his year of service in the U.S. Army during World War I. Leveraging his lieutenant status, he furthered the cause for men in dance by offering his unique perspective that military training and dance training were comparably rigorous. Shawn established himself as a dancing warrior, appearing in dances such as his solo Japanese Spear Dance (1921) and a group number, Maori War Haka (1934).

Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers (1933-1940)

Following the dissolution of Denishawn, Shawn gambled his entire artistic, financial and social worth on a venture to form the first-ever all-male dance company. Between 1933-1940, Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers toured theaters, colleges, and gymnasiums throughout the depression-era United States with a repertory of dances that dramatized Shawn’s contention that dancing shared an affinity with revered spheres of physical activity, such as the military, religion, labor, and sports. The company rode a wave of interest piqued by Muscular Christianity, a Progressive era social movement that emphasized the links between patriotism, athleticism and religiosity. In the U.S., Muscular Christianity promised to rescue “Christian manliness” from the supposedly enervating effects of modern and urban living.”Putney, Clifford. Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2001: p. 1. The doctrine undergirded the foundation of the Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) in the U.S., perhaps most especially a branch in Springfield, Massachusetts, that later became Springfield College, which by 1930 had become a preeminent center for training physical educators. In 1933, at the invitation of the Springfield College president, Shawn began to teach dance classes to the physical education students and successfully recruited several into his fledgling men’s company. His association with Springfield’s excellent program paved the way for booking the company at local high schools and colleges across the country. Moreover, the company’s affiliation with Springfield attracted the attention of sports writers who reviewed their concerts in local newspapers, many of which printed a variation of Shawn’s press release that his company represents “the right kind of dance for American men…and will give satisfaction to all American men either as spectators or participants.”“‘Music and Ballet’ [sound recording]: Commentary and Music.” (Radio interview with Irving Deakin and Ted Shawn), March 10, 1938. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library. Most writers assured readers that Shawn’s dancers were “normal athletic men” and not “St. Petersburg prancers in disguise,” emphasizing how whenever they were not dancing, they were involved in physical labor—from farming to cabinetry, stonework, cement, chopping trees, firewood—at Jacob’s Pillow, where his men’s company spent the summer months rehearsing and running a training camp. One of the most successful tools for recruiting young athletes to Shawn’s camp was Olympiad (1937), a suite of dances based on various sporting events—the decathlon, basketball, fencing, and boxing as well as cheerleading and color guard—most composed by the athlete-dancers in Shawn’s company.

Yet another influence on Shawn’s exploration of masculinity in dance were the radically transforming principles and practices of modern labor. Even as Shawn upheld dancing’s spiritual dimension as an antidote to the encroaching mechanization of the modern world, he also presented his Men Dancers as ideal embodiments of Taylorism—efficient, reliable, durable laborers. Programs for the Men Dancers’ first tour included two spectacles of labor: Cutting the Sugar Cane (1933), a study in the choreography of agricultural work and Japanese Rickshaw Coolies (1933). Shawn’s fascination with the intersection between labor and dance received its fullest exploration a year later with Labor Symphony (1934), a four-part dance that explores the choreography of physical labor—in the fields, forest, sea, and factory.

The final section is a stunning “machine dance” wherein the dancers perform elaborate sequences patterned after automated pistons, cogs, and gears. In one section, the dancers form a living telegraph: their lower bodies create the machine’s pulsing rhythm with stringent sideways strides as their sleeve-covered arms slide across their bare chests, giving the appearance of spewing dots and dashes of a ticker tape.

Credo: Male Dancer as Creative Artist

Shawn sought to legitimize the male dancer by framing him as a clergyman, a warrior, an athlete, and a worker, though he was ultimately most invested in convincing the public that dancing was an art and the male dancer, a creative artist. Some of Shawn’s most significant dances were based on literary or philosophical sources. For instance, O, Libertad! (1937) Shawn’s first full-length dance, took its name from a poem by Walt Whitman, a constant source of inspiration for Shawn.

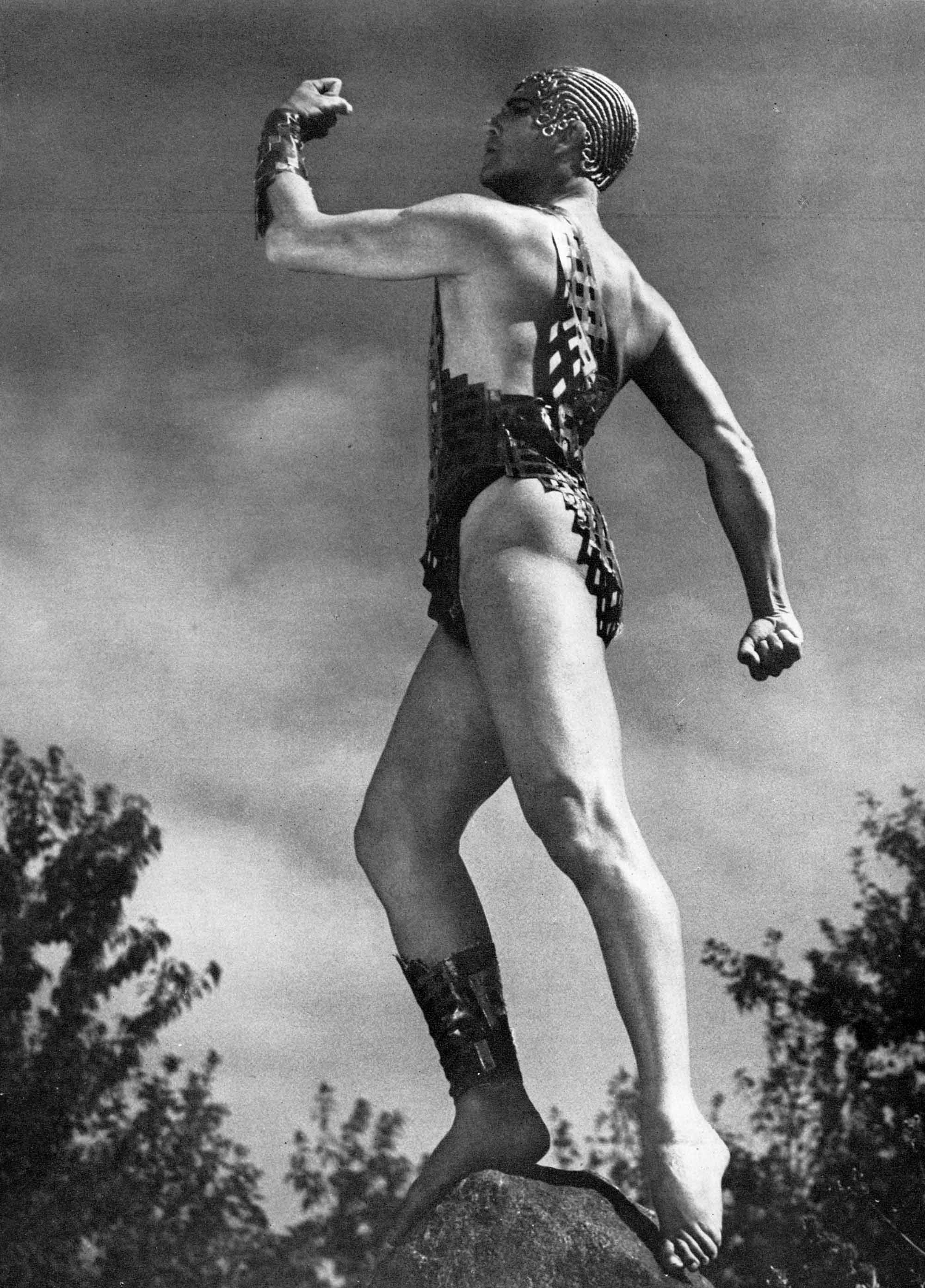

A “rhythmic biography of America” in three acts, the dance dramatized moments in the history of the Americas from Montezuma to modernism. The dance’s dramatic turning point were two related solos “Modernism” and “Credo” performed by Shawn. In the program notes, Shawn remarked that it was no coincidence that the “peak of modernism in the dance” coincided with the depression. In “Modernism,” he appears as a masked hag wearing a cloak emblazoned with a graph the plummeting line to symbolize the stock market crash of 1929. A disturbing convergence of two exemplars of modern dance, Mary Wigman’s Witch Dance (1926) and Martha Graham’s Lamentation (1930), Shawn’s “Modernism” is a hostile choreographic rejection of expressionism in dance in general and Graham and Wigman specifically, both of whom leveled criticism at him and his work. Immediately following “Modernism,” Shawn disrobes, revealing himself in a strongman’s one-shouldered singlet and arm and leg cuffs performing a sequence of poses, twirls, and militaristic gestures, as if he were a futuristic messianic figure leading the masses to its future. Shawn described “Credo” as his “autobiography in movement” and that the dance was meant to convey his personal belief about dance’s capacity to heal physical trauma and social upheaval. Ironically, here he performs his dance as a weapon against modernism, a vital social and aesthetic movement that he himself helped to vitalize, giving choreographic form to his belief that the male artist can rescue dancing from the degeneracy of modernism: “Only where dancing has degenerated has it become dominated by women, who have used it largely to express the trivial, the superficial and the merely pretty. But the dance, in its fullness, demands strength, endurance, precision, perfect coordination of mind, body and emotion, clarity of thinking, creative power, and organizing genius—all distinctively masculine qualities.”Shawn, Ted. “Principles of Dancing for Men,” The Journal of Health and Physical Education, vol. 4, no. 9 (November 1933): 27-29, 60-61. On some level, Shawn’s defense of the male dancer was an offense on women dancers that belied his full-throated admiration for Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, whose dances, he thought, were ideal expressions of beauty and the divine.

In several other dances, Shawn’s played a version of his “Credo” character, a misunderstood visionary who is ostracized or otherwise repudiated for his capacity to live on a more enlightened plane. This was the theme of The Divine Idiot (1930), Shawn’s choreographic treatment of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, wherein he plays the philosopher who becomes undone by his attempt to convince the citizen-slaves that a world of reality that beyond their comprehension.

He also adopted a similar persona in the culminating section of Dance of the Ages (1938).

Inspired by Edward Carpenter’s Toward Democracy (1883), the gay writer’s prose poem that celebrates society’s march toward a cosmic “freedom,” Shawn created a dance in four sections, each dedicated to a different element (fire, earth, water, air) and an affined principle of leadership, power and social formation. As soloist, Shawn often appears as a leader among men, cajoling his followers into “a higher existence and a life of greater dimension.”“Commentary: Dance of the Ages” (sound recording). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library. *MGZTL 4-44)

Though Shawn imbued his dances with elaborate cultural, religious, and historical references, his ultimate pursuit was creating dances for aesthetic experience, convinced that he could encourage modern audiences to appreciate the male body as an object of beauty. In Death of Adonis, (1923), a “sculpture plastique,” Shawn appeared on a plinth in the nude but for a fig leaf and a thin coat of white body paint that gave the illusion that he was a “living sculpture,” as he made his way through a series of poses.

The dance fulfilled a promise Shawn had made in 1917 that American audiences would be prepared to tolerate nudity on stage: “To see the naked body of one who is healthy, strong, symmetrical and of noble proportion is to experience a sense of divine revelation, and one is moved to something akin to exaltation.”Shawn, Ted. “Is Nudity Salacious?” Theater Magazine, November 1924, 12.

Rhapsody Op. 119 No. 4 (1933), was one of Shawn’s early “music visualization” dances for men.

Its success proved significant to Shawn’s decision to form an all-male company. A modern exercise in male bonding, the dance is composed of a series of intricate figures and formations that evoke maneuvers of soldiers on a covert mission. They lead and follow one another, shoulder each other’s weight, retreat blindly in phalanx, and form human chains that twist and knot yet prove resilient under stress. The dance had its first audience at the posh Surf Club in Miami Beach, as the entertainment for a special dinner hosted by the President of the Woolworth Company and his guests, most millionaire captains of industry, who had expected to see dancing girls for their entertainment. Shawn was shocked to learn the positive reaction to his new work and that audiences might actually tolerate—perhaps even take pleasure in—his vision of male beauty on stage.

Shawn upheld his defense of the male dancer for over a half century—from his earliest years as a dancer to his final days as an internationally renowned legend. His effort unquestionably opened the door for generations of men to enter the professional dance world, among them Gene Kelly, who once confided to Shawn that his decision to become a dancer was inspired by his experience seeing Shawn and His Men Dancers when the company performed at the future movie star’s high school. Over the years, Shawn championed the careers of several men, above all his lover and protégé Barton Mumaw, as well as ballet stars Erik Bruhn and Edward Villella, each of whom appeared regularly at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Though a stalwart proponent of men in dance, Shawn did not support all male dancers. Indeed, he openly repudiated those he deemed effeminate or flamboyantly homosexual, even though Shawn acknowledged his own homosexual tendencies since adolescence. Unwilling to compromise his impeccably rehearsed embodiments of masculinity both on and off the stage, Shawn distanced himself from dance icons such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Paul Swan, and later, Rudolf Nureyev, whose extravagant personalities and stage presences raised the specter of homosexuality, which Shawn considered a serious threat to the strides he had made toward establishing acceptance for the male dancer with middle America, not to mention a threat to his own status as the “Father of American Dance.”

A New Ted Shawn Biography

PUBLISHED July 2019