Introduction

Few dancers, in their debut performances at Jacob’s Pillow, can have made an entrance as head-turning as Jason Samuels Smith’s. It came at the end of the season-opening gala in 2009, and for much of the audience, the dance began as a sound. People had to twist in their seats to find the source: Smith ringing complex music off the theater’s wooden aisles, testing out the whole of the theater before sliding smoothly down to the bottom of the raised stage and tapping up the stairs, alluding to the stair dance of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson as he ascended. Dancing onto an amplified wooden platform, Smith asked, “How y’all doin’ tonight?”

What followed was a feast of rhythmic brilliance, a nearly fifteen-minute flow of ferocious technique and astonishing invention. Such a variety of tones and tactics and modes of attack: pounding, lightening up, pausing wittily. Smith’s attitude was cool, in control, but his was a mind operating at lightning speed, releasing a reservoir of hard-won material, one idea igniting the next. As both his body and the beats it was throwing down doubled back on themselves, old steps were transformed and reanimated, new patterns and pathways blasted open. Amid waves of applause, even Smith had to stop and acknowledge the awesomeness of it with a sly smile.

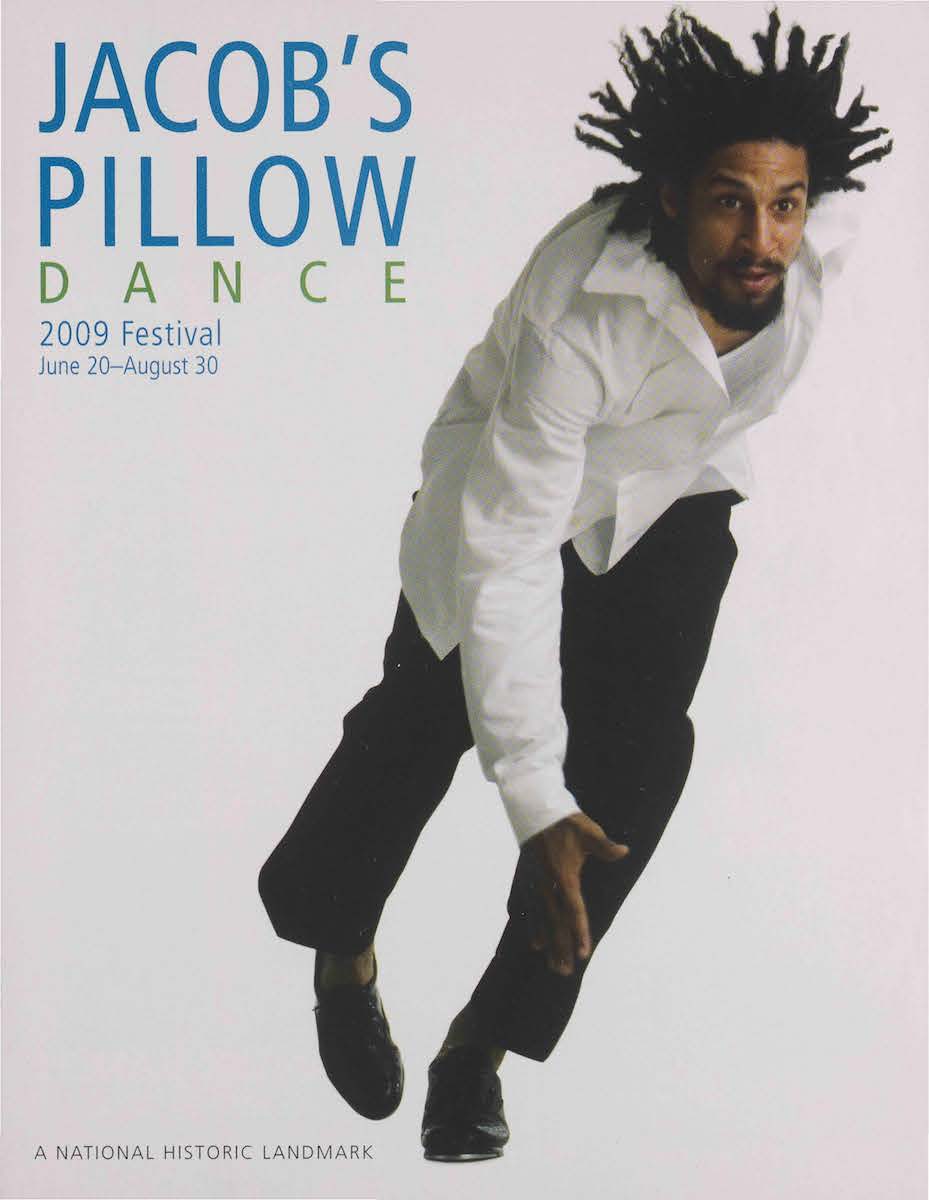

“I knew the theater was made of wood,” Smith would recall, “and I wanted to use as much of it as possible.” It’s not so often that tap dancers are invited to play on such a fine instrument, much less allowed free rein. It meant something for a tap dancer, especially a black one, to occupy the Ted Shawn Theatre, named after the Pillow founder who had labeled tap “the invention of the devil,” defined its African-American origins as “alien to American nature and temperament,” and deemed it unworthy of admittance to his home for dance. But the 29-year-old Smith was no thief in the temple. His photo was on the cover of the season brochure. His company was about to command a two-week run.

The Kid from Hell’s Kitchen

Smith was born into dancing. His father, Joseph “Jo Jo” Smith, was a noted jazz and disco dancer, the proprietor of Jo Jo’s Dance Factory, a training ground for Broadway and television performers. His mother, Sue Samuels, had been a student of Jo Jo’s before she became his wife, assistant, and co-director of the studio. Even after the studio shifted names and ownership—eventually becoming Broadway Dance Center—she continued to teach Jo Jo’s style of jazz. Jason and his sister, Elka, grew up around the studio, absorbing information daily, in and out of class. For a New York City boy who identified as black, this in-the-family exposure to dance made it seem a natural activity but perhaps not a very cool one. That is, until he was eight and a black kid just a few years older started teaching tap.

The older boy was Savion Glover. In the reawakening of tap that was unfolding in the 1980s, Glover had become the chosen one. He was the child picked to inherit the knowledge and experience of aged hoofers who had danced with the great jazz bands of the 1930s and 40s, had struggled as the commercial demand for tap dried up, and had recently emerged from semi-retirement. Glover had danced alongside these men and learned from them in the Paris revue Black and Blue and would again when the show transferred to Broadway in 1989. Already, Glover was transmitting this knowledge to people his age and younger, making tap look like a young person’s art again in challenging classes and on Sesame Street, where Smith joined him for several episodes. When Glover went away, touring with the Broadway show Jelly’s Last Jam, Smith’s interest in tap waned.

Smith was part of a generation of tap dancers inspired by Glover, a generation that would confront the difficulty of developing their own individual styles under his dominating influence and of pursuing careers in the shadow of his stardom. That influence and fame swelled greatly with the 1996 Broadway show Bring in ‘da Noise/Bring in ‘da Funk, choreographed by and starring Glover. The show connected tap history, reaching back to slavery, with African-American history extending into contemporary discrimination. Glover’s choreography drew a line from tap’s beginnings to his own style, fast, loud, and aggressive, akin to bucket drummers and attuned to hip-hop.

The production needed to train young black men to do that choreography. Smith became an understudy at fifteen. At first, the other dancers called him “Mudfoot” on account of his sloppy footwork, but he worked harder to improve than almost anyone. Eventually, he stepped into most of the roles, including the lead. The show was “my college, my university,” he remembered.

After Bring in ‘da Noise closed, Smith joined Glover’s company NYOTs (Not Your Ordinary Tappers). They appeared in the opening credits for Monday Night Football, in Glover’s ABC special (with Puff Daddy, among other celebrities), and in a PBS performance at the White House. And then Glover moved on to other projects, other dancers.

Rather than giving up, Smith dug in. Obsessively studying such jazz legends as Charlie Parker and footage of great hoofers, he gleaned not just steps and rhythms but also style, reaching past Glover into tap history to find materials and inspiration so that he might create and discover his own style in the present. Smith tried to learn from everyone, and he put in the work, hours upon hours of solitary practice to master what everyone else could do and invent variations and devious maneuvers no one else had even imagined: high-powered, rapid-fire steps turned inside out and relocated to uncommonly used edges of the feet.

At tap festivals around the world, he overtook Glover as the most copied dancer, the archetype of an era. He became a teacher and a leader, co-founding the Los Angeles Tap Festival in 2003. At tap festivals around the world, he overtook Glover as the most copied dancer, the archetype of an era. His choreography for the Jerry Lewis/MDA Telethon was the first tap number to win an Emmy Award since a Fred Astaire special in 1959. He was invited to participate in the popular “Fall for Dance” festival at City Center in New York, and a 2007 appearance on the hit TV show So You Think You Can Dance? brought him wider fame. The dancewear company Bloch started selling a Jason Samuels Smith tap shoe designed by him. A chance meeting at the American Dance Festival led to India Jazz Suites, a concert tour and documentary film with Chitresh Das, a venerable master of the Indian percussive dance form Kathak. The project and the friendship at its heart said much about Smith’s wide-ranging curiosity, his hunger for information and fresh challenges (such as Kathak’s fractional meters and rhythmic cycles), his humility and respect for his elders.

Impressed and energized by the younger dancers he met at jam sessions he organized in Los Angeles, Smith formed his own company. The name of the troupe, Anybody Can Get It, was a nod to the friendly exchange of steps and ideas in jam sessions, a group ethos. But it was also the welcoming gesture of a tap evangelist. “Don’t be afraid of tap,” it said; “come with an open mind and enjoy.” The company’s two-week run at the Pillow in 2009, which coincided with the announcement that Smith had won a Dance Magazine Award, was a good chance to show what he meant.

Anybody Can Get It at the Pillow

It was a family affair. Along with his company, a pianist, and a bassist, Smith brought along his father on percussion; they traded beats to Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father.” His cousin rapped, and Smith dropped some rhymes, too. Significantly, three of the company’s four dancers, apart from Smith, were women: Chloe Arnold, Melinda Sullivan, and Sarah Reich. During a post-show discussion, Smith asserted that some of the best tap dancers of the day were women. The ones he brought to the Pillow, present and future leaders of tap, proved the point nicely. (The other guy, the tall and quick-witted Lee Howard, was no slouch, either.)

The group had emerged out of jam sessions, and so Smith included two jam sessions per show: three dancers trading impromptu ideas and challenging one another. Track the interplay here among Smith, Reich, and Howard:

Each dancer was an accomplished improviser, yet Smith also wanted to show their tight coordination in choreography that was rhythmically and physically complex. In his New York Times review, Alastair Macaulay noted: “It’s already a pleasure when five dancers establish one rhythm together; it’s another when they embellish it together; and yet another when the unison is sustained as it keeps changing in meter, emphasis, and texture.”“Where a Week’s Typical Fare Is Beyond a Standard Plié” by Alastair Macaulay in The New York Times, July 26, 2009

Macaulay also praised Smith as “an easy enthusiastic communicator.”“Where a Week’s Typical Fare Is Beyond a Standard Plié” by Alastair Macaulay in The New York Times, July 26, 2009 Listen below as Smith, during a post-show discussion, explains improvisation (“I may have an idea of where I’m going to go but I don’t know how I’m going to get there”) and how, through improvisation and shared invention, the vocabulary of tap is always expanding:

“Last week, I fell,” Smith says here. “But I was reaching.” You can sense that unceasing search, that constant striving, every time that Smith takes a solo. It’s true whether it’s his turn in a group relay (pay attention to the awed pleasure in his company members’ reactions—that’s an indicator of fresh creation) or time for him to spread out in a number all his own, ruminating, experimenting, pushing the envelope of his art.

In his program note, Smith honored “dancers who didn’t get to the Pillow” and stated his hope that he “wouldn’t have to wait years to get invited back.” It took seven. In 2016, he returned for And Still You Must Swing with Dormeshia and Derick K. Grant, old friends from his Bring in ‘da Noise beginnings. These dancers were peers, all in their prime with decades of devoted study of tap under their belts. For the choreography that Smith contributed (below) he knew he could be as intricate and subtle as he liked, sure that his colleagues could keep it swinging and keep upping the ante for one another in improvisational exchanges. Their mutual delight is part of the dance.

In his solos, Smith was still reaching. In the final show of the run, he recognized the presence in the audience of the tap doyenne Dianne Walker, saying that the show was “all about you and everyone else that got us here.” And then, weaving together worshipful invocations of past masters with his own latest innovations, Smith showed, once again, what “here” meant: not just Jacob’s Pillow but an American tradition, an American art, that Smith and his colleagues had inherited and were extending into the future.

PUBLISHED June 2017