Circus and Dance

The great French mime Marcel Marceau once remarked that “the circus and choreography, expressions of the same art, turn up their noses at one another today, after having been in the eighteenth century one and the same spectacle.”Senelick, L. (1998). Circus. In (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Dance. : Oxford University Press,. Retrieved 7 Feb. 2019, from http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195173697.001.0001/acref-9780195173697-e-0387. While Marceau may have been exaggerating, certainly dance acts have been involved in circuses since the 18th century, as well as equestrian ballets and rope dancing. The strength, grace, vitality, and precision necessary for such pursuits lives equally in the worlds of circus and dance.

A circus is not just the company, but also the performance itself: usually a series of acts choreographed to music, typically taking place in a ring and, since the late 19th century, mostly taking place under a tent commonly called “The Big Top.” The spectacle of traditional circus serves up drama and physical display in equal measure, thrumming with familiar characters: clowns for pathos and humor, charismatic ringmasters, acrobats atop elephants, strongmen and tightrope walkers, trained animals, and other stunt-oriented artists. Anyone who has ever seen the split-second timing of the Flying Wallendas, the unison beauty of cantering matched horses, the physical agility of a contortionist, or the smooth catch of a person from a swinging trapeze understands the implicit choreography of the circus. Historically, European circuses employed dancers and choreographers who brought simple familiar steps or dances onto horseback or highwire, especially in the late nineteenth century. By the twentieth century, argues theater historian Laurence Senelick, “dance dwindled in importance in the American circus with its competing three rings and emphasis on immediate sensation.”

Whether or not dancers remain essential to circus, the circus has been essential to dance. For example, in her 1939 work Every Soul is a Circus, choreographer Martha Graham counted on us knowing the tropes of the circus as she set herself in the midst of a love triangle with Merce Cunningham and Erick Hawkins. One of her rare humorous pieces, Every Soul is a Circus has both physical exuberance and poignant clowning. Around the same time as Graham was using the circus for narrative significance, George Balanchine went beyond the symbolic. Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey Circus commissioned Balanchine to choreograph a ballet involving the circus’s famous elephant group. The resulting 1942 work, Circus Polka, with music commissioned from Stravinsky, was first performed by elephants, and then restaged for students in the School of American Ballet (renamed Adventures in Ballet). Balanchine later remembered that he telephoned his frequent collaborator Stravinsky when the choreographic commission was offered and the conversation went something like this: Balanchine: “I wonder if you’d like to do a little ballet with me.” Stravinsky: “For whom?” Balanchine: “For some elephants.” Stravinsky: “How old?” Balanchine: “Very young.” Stravinsky: “All right. If they are very young elephants, I will do it.”

In the 1960s, a performance trend called Nouveau Cirque, or New Circus, started in France. While flippantly defined by Robert Shore in Time Out London as “Old Circus minus the animals and performed in theatres rather than big tops,”Robert Shore, Time Out London New Circus uses traditional circus skills but may also tell a story or have a theme. Theater critic David Adams defines New Circus as:

an uncategorisable mix of theatre, dance, mime, music, comedy—and circus techniques. The shows [are] pure magic, and I guess that’s at the heart of circus, old or new. Magic performed with consummate skills that can take your breath away. That idea of spectacle gives circus its roots in the oldest performances known to humankind—rituals and dances…and magic…. Many of this new generation of performers wanted to make circus more theatrical and use circus techniques to create something that was removed from the clichés of the Big Top.David Adams, “New Circus,” The Western Mail 28 October 2005 http://www.theatre-wales.co.uk/critical/critical_detail.asp?criticalID=208

After its early days in France, New Circus, also sometimes referred to as contemporary circus, took hold in Australia during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and spread to the West Coast of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Circus at the Pillow

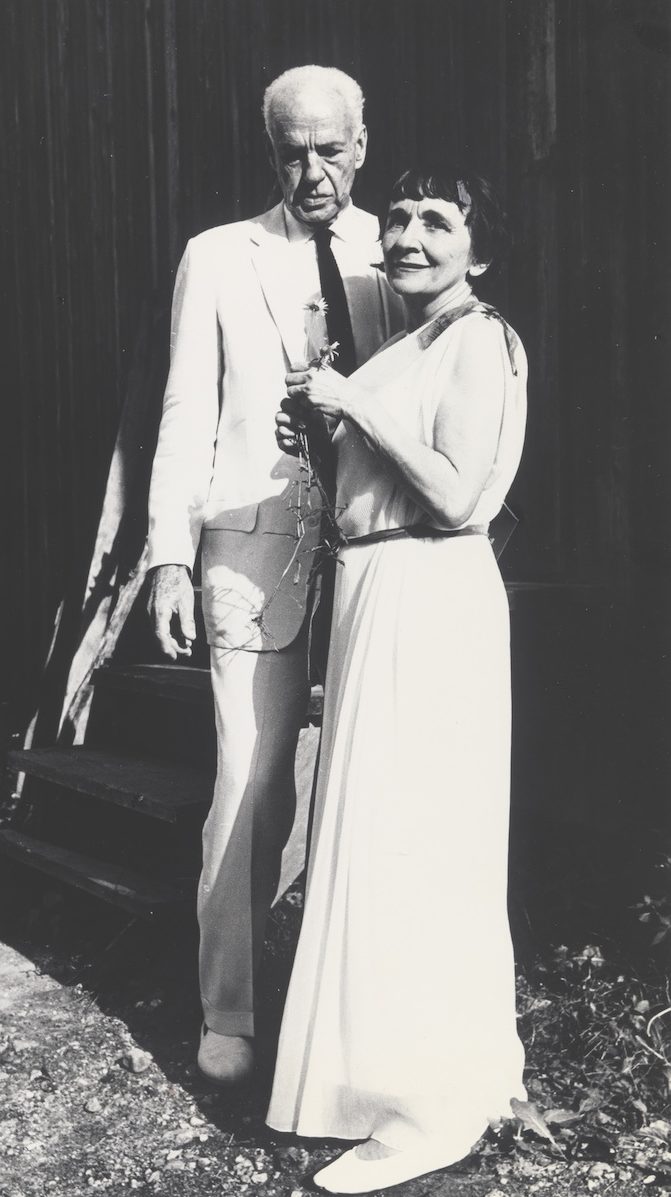

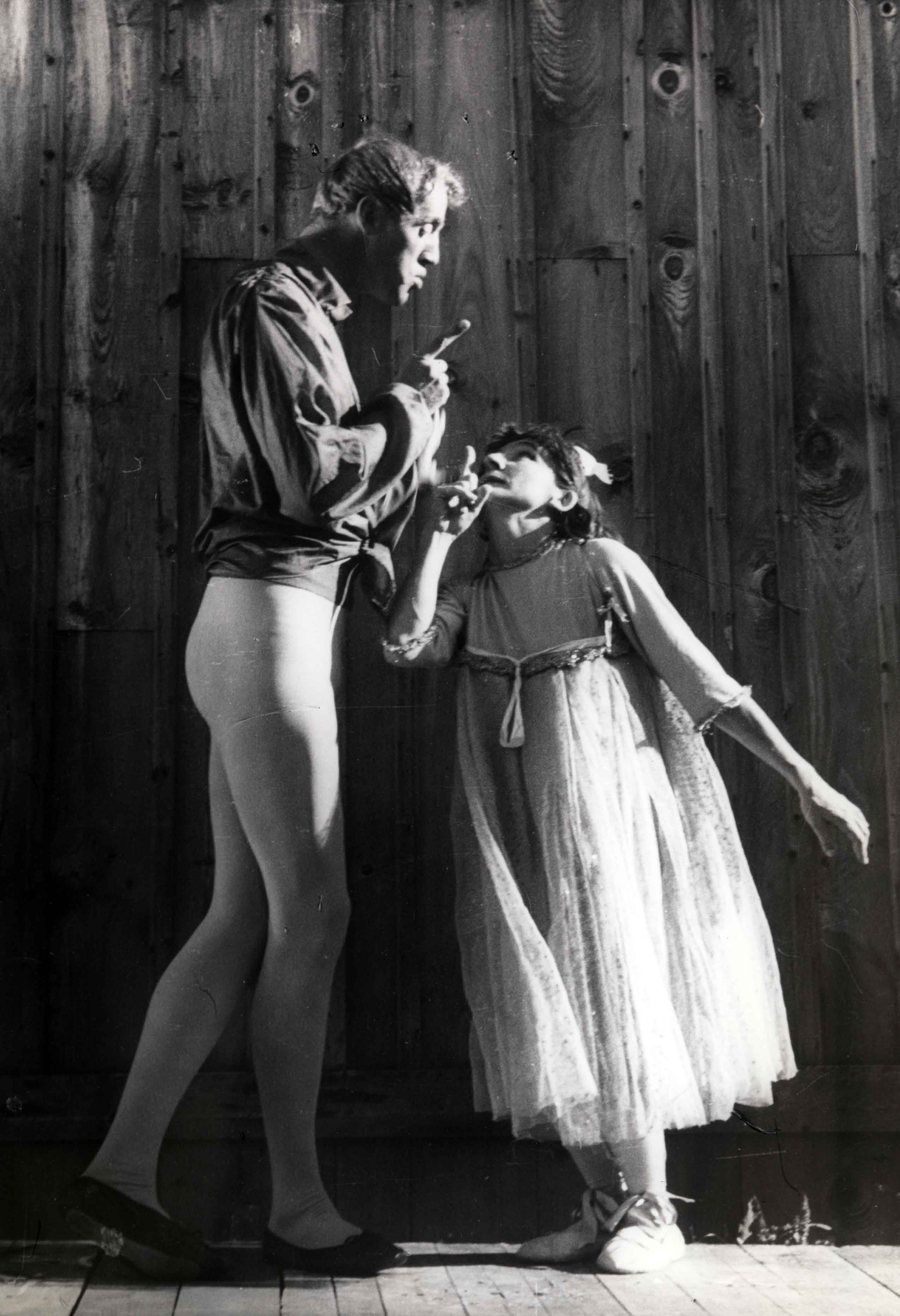

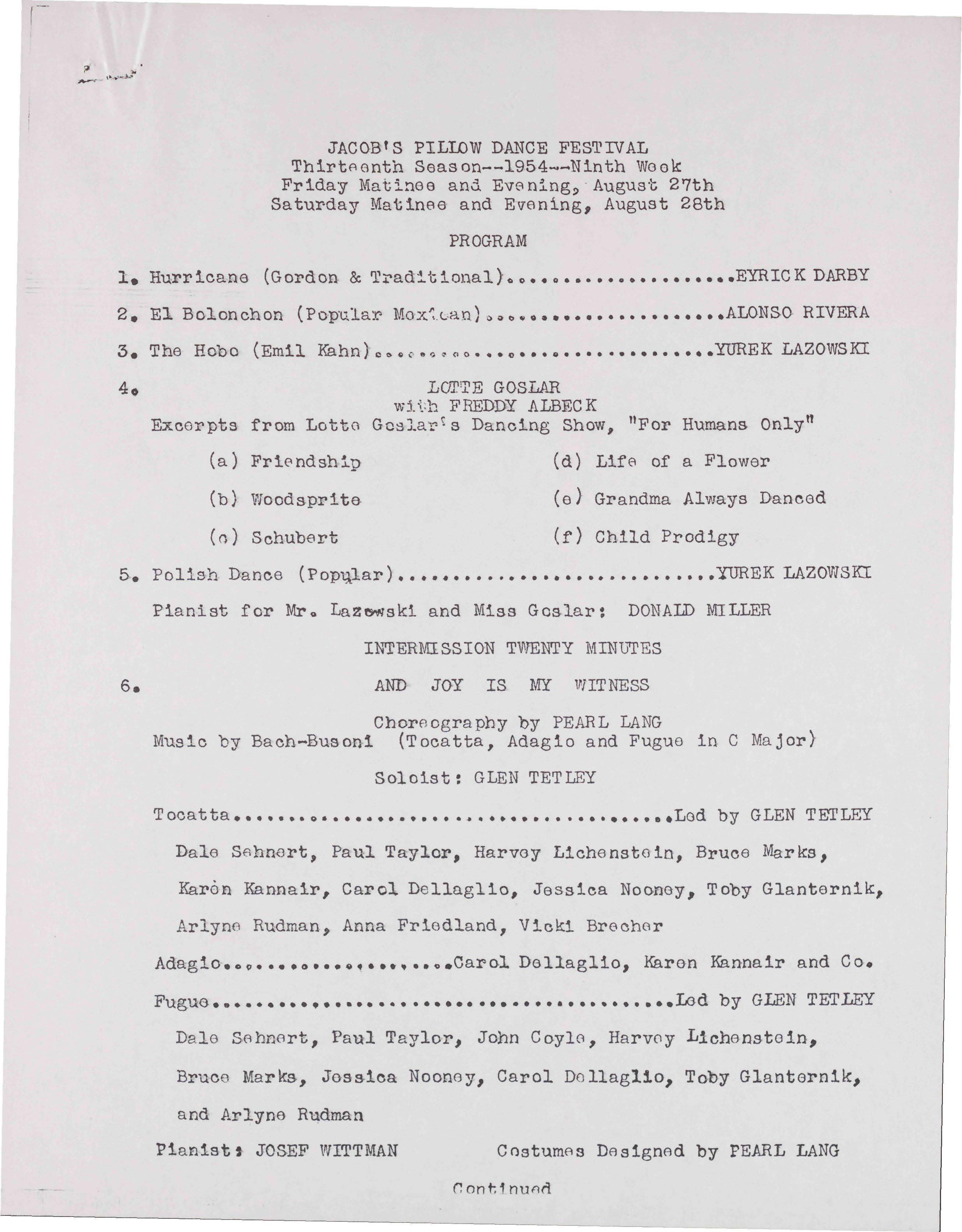

Jacob’s Pillow has presented circus within the frame of a dance festival from the very earliest days of the festival. Lotte Goslar is a notable example of Pillow founder Ted Shawn’s broad definition of dance.

Goslar, who trained as a modern dancer with noted German choreographers Mary Wigman and Gret Palucca before turning her attention to mime, frequently appeared on the mixed-bill Pillow programs.

Her company, Lotte Goslar’s Pantomime Circus also performed at Jacob’s Pillow. Appearances by noted clown Bill Irwin continued the tradition of circus at the Pillow.

In the 21st century, both circus and new circus have thrived at Jacob’s Pillow, with striking performances by companies such as Circa, Inbal Pinto, and the presentation titled Leo.

Circa

Circa. Approximately. Roughly. Around. Circle. Circus. All of these and none of these synonyms are apt metaphors for the company Circa. The members of the company more than approximate athletes, acrobats, dancers. Their works circle from circus to theater to dance and back again. The company, based in Brisbane, Australia, is led by artistic director Yaron Lifschitz. Lifschitz, who trained as a director and has worked in opera, theater, and physical theater, has found his theatrical home with circus, stating that his “passion is creating works of philosophical and poetic depth from the traditional languages of circus.” Different paths of training, all extremely physical, shaped Circa performers, some in expected ways, some less so. Training in gymnastics and acrobatics is put to use, as are backgrounds in break dancing, synchronized swimming, and modern dance. Skills on a trampoline serve alongside excellence in handstands and on teeterboards. In an interview with the Belfast Telegraph, Lifschitz described how the shows evolve, stating that he takes “all the things people do in circuses, ‘from jumping on each other, doing acrobatics, bouncing on their hands, hanging off trapezes, flying through the air, tumbling … all the languages of circus … to re-imagine these as the palette for making extraordinary works of performance.’”“A flying circus of dance and amazingly physical theatre.” Belfast Telegraph October 26 2010 https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/a-flying-circus-of-dance-and-amazingly-physical-theatre-28566814.html

Circa strips away expectations of the circus, and even the circus as it relates to dance. As James Woodall of The Art Desk writes: “Though the performers might pay tribute to circus, there’s no ‘circus’ here: no flames, no hurdles, mercifully no animals, no paraphernalia. No clowns. The guys, in cotton trousers, are bare-torsoed; the girls are in swimsuits. That’s it.”James Woodall, “Circa, Barbican Theatre.” 12 March 2010 https://theartsdesk.com/dance/circa-barbican-theatre

Once they’ve removed all of the expected trappings of the circus, what’s left? What Circa keeps and where they start is simply the human body. They trust the body’s ability to make meaning, grounding their work most assuredly in the world of concert dance. As Circa themselves explain: “In the circus we don’t need words to communicate. Instead we have the most magnificent expressive vehicle of all—the human body. Our bodies speak of pain and joy, of hope and despair, of love and loss, of courage and timidity. The list goes on and on and the words pile up.”

By stripping down their circus to a very human scale, and removing the accessories of spectacle, the resulting works become spectacular in a whole new way. These performers show that the fallible, fragile human body is not a fantasy superhero, but instead, very real, and very capable of extraordinary things.

Circa performances herald a contemporary approach to circus, focusing attention on the overall aesthetic impact, rather than episodic spectacle—though there is spectacle aplenty and theatricality. From the first explosive dive on to the stage, we know we are in for a physical adventure. We see aerial work, ring tossing, balancing, and partner work.

Former Pillow executive and artistic director Ella Baff talked about the connection between circus and dance to describe Circa.

Inbal Pinto Dance and Oyster

Israeli choreographer Inbal Pinto came to dance from a background in visual arts. Prior to joining Batsheva as a dancer, she had a job creating window displays (as did the choreographer Paul Taylor). Her interest in visual arts has had a profound influence on her choreography. In 2001, Pinto presented her circus-influenced work titled Oyster at Jacob’s Pillow.

Pinto made the work in collaboration with the piece’s director, Avshalom Pollak, whose background is in theater, film, and television. In a PillowTalk, Pinto and Pollak explained that the title comes from the sound of the word “oyster” as well as the image of an oyster as a theater that opens up and reveals a pearl inside. They went on to connect that to a metaphor for what performers do, digging inside themselves for treasure. Pinto’s visual imagination directed the work, with the performers’ physicality providing the means to explore her abstract vision. Oyster is a surreal world to observers, although it makes perfect sense to its inhabitants.

In the same PillowTalk, Pinto identified two performance traditions that influenced her in creating Oyster. First, German expressionist dance, particularly the work of choreographer Pina Bausch. And, second, Pinto was explicitly inspired by traveling circuses, which Pinto called, “a circus of life.” Pillow Scholar Suzanne Carbonneau commented in her PillowNote, “This giddiness surely owes something, too, to Pinto’s avowed interest in clowns, particularly those film comedians whose art was put at the service of disrupting social conventions and commenting on the heartlessness of modern world.” Oyster’s performers, six of whom identified as dancers and four as actors, collaborated to build both the movement worlds of the work, as well as the sense of character. The characters may feel familiar from circus acts or sideshows, with Pinto and Pollak guiding the performers to abstract them through movement investigation. Pinto is deeply intrigued by a wide array of movement possibilities, the ways in which ordinary people move, mechanistic movement, movement for overly long limbs, and movement with no limbs at all.

Like the best clowning in traditional circus, Oyster has unpredictable humor, and perhaps less familiarly, a macabre sensibility. From the movement itself, to absurd situations created through interaction, the relationships between the characters who people this world raise questions about the tenuous line between support and control. Much as a diverse group of circus performers might have found solace in a freakshow life in the past, Oyster reveals a community united by a life they’ve chosen, making them extraordinary and beautiful in this world.

LEO

When the Great and Powerful Oz instructed Dorothy to “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain,” he could well have been telling audiences how best to observe theatrical illusion. Much theatrical spectacle depends on the audience’s willingness to accept the artifice of theater, as if believing the magic of the moment means not looking at how the magic is achieved. LEO simultaneously presents the illusion and shows what is behind the curtain. Two versions of a solo performer, one in the flesh and one simultaneously projected appear. The projected image, although rotated 45 degrees, is as close to the tangible as possible, life-sized and displayed in real time. The stage is divided; each of the men in his own tiny room, but what is up and what is down becomes muddled. Set up side by side, audience members choose whether to watch the real or the illusion. Seeing the unreal only makes the real more extraordinary. The combination of the performer, the video and animation technologies, means even when the audience understands what’s going on, they still can’t believe their eyes.

LEO is new circus, it is dance, it is theater. It is the story of an ordinary man who cannot take his physical world for granted. LEO is the result of artistic and physical inquiry. Physical, creative, and intellectual curiosity. The creative team behind LEO started with a question, which one German newspaper summed up as “Have you ever tried to run up your living room walls?” and then set out to answer that question in the most impossible and slightly magical ways.

The original idea for LEO came from performer Tobias Wegner. German born Wegner’s background is in New Circus; he is a graduate of the Belgium University of Contemporary Circus Arts. Like the best of circus performers, Wegner has variously been described as an actor, trampolinist, gymnast, clown, and a dancer. Wegner and his collaborators, director Daniel Briere and creative producer Gregg Parks, brought the worlds of physical theater/circus into conversation with technology: video projections and animation technology are integral to the performance of LEO. In an interview with Vaudevisuals, Wegner explained that he got the seeds of the idea for LEO while still training in contemporary circus arts.https://vaudevisuals.com/category/leo-mind-bending-physical-theatre/ After trampoline class, he and his colleagues would literally try to run up the walls. As he noted in the interview, it was not a new idea. Fred Astaire memorably danced on the ceiling and walls in Royal Wedding (1951).

That said, it all comes back to the performer. LEO offers a new way to experience the extremes of new circus and the visceral pleasure in viewing dance mediated by technology. LEO, like works by Circa and Inbal Pinto’s Oyster, is an elixir resulting from the combination of dance and circus. They share magic, vitality, and physical spectacle, giving visceral pleasure in viewing dance.

For further viewing

PUBLISHED February 2019