Introduction: Convergent Histories—Dance and the Visual Arts

The experimental climate of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States is often cited as the midcentury apex for socially transgressive and politically progressive art. Allan Kaprow’s Happenings and the experimental performances of Judson Dance Theater were among the counterculture movements that energized and engendered social, aesthetic, and political challenges to the status quo, questioning formal properties of artmaking. Radical arts practices imploded the boundaries of movement and form, drastically reconfiguring aesthetic conventions in dance and the visual arts. During this period, artists expressed anti-authoritarian commitments by creating works that exposed exclusionary politics at institutional levels. Institutional critiques offered across places of production questioned the right of the establishment to define the limits and location of artmaking, and to determine who qualifies as being an artist. As visual artists began questioning the institutional stronghold of galleries and museums, choreographers challenged the so-called decontextualization of the proscenium stage. Social situations produced by artists in alternative spaces sought to blur art and the everyday, calling upon the energy of civic participation to collectively create and/or sustain the work, while simultaneously reconsidering how bodies within artistic contexts interact with their environments.

Stephanie Rosenthal, curator of the ground-breaking 2012 exhibition Move: Choreographing You, addresses these convergent histories writing, “The interest—shared by an entire generation of visual artists—in the unique event, in playfulness and an exploration of one’s own body, was reflected in the developments in postmodern dance.”Rosenthal, Stephanie, Susan Leigh Foster, André Lepecki, and Peggy Phelan. 2011. Move: choreographing you : art and dance since the 1960s. London: Hayward Pub. Visual artists like Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, and Dan Graham, to varying degrees, rejected object-based practices, instead turning their bodies or the bodies of their viewers into the foundational material of artistic inquiry. Arguably, visual artists began making dances. And, as choreographers began developing work for museum settings and unconventional spaces, dancemakers like Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and Simone Forti developed installation pieces and site-specific works that explored pedestrian movement and everyday activity. The choreographies produced were de-theatricalized and task-oriented, which often resulted in the suppression of any clearly identifiable linear structure and an embrace of multiple meanings. As disciplinary boundaries began to deconstruct, new directions in the fields of dance and the visual arts multiplied.

Of course, the proliferation of interdisciplinary collaboration and creative cross-currents taking place between the visual arts and dance during the 1960s and beyond is not without precedent. Collaborations between choreographer Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage, and visual artist Robert Rauschenberg preceded and deeply informed the postmodern experimentations of Judson Dance Theater. The collaborative relationship between Cunningham-Cage-Rauschenberg began in 1954 with Theater Piece No. 1, an untitled event organized by Cage at Black Mountain College. Rauschenberg would go on to design sets, costumes, and lighting for over twenty of Cunningham’s choreographies including Minutiae (1954), Summerspace (1958), Antic Meet (1958), and Travelogue (1977). A notable Cunningham-Rauschenberg collaboration that premiered at the Pillow was Nocturnes (1956). In addition to his long-term collaboration with Cunningham, Rauschenberg also designed sets and costumes for Trisha Brown and Paul Taylor. Set and Reset (1983), choreographed by Brown with designs by Rauschenberg, is indicative of the sensuous saturation that can take place when dance and the visual arts converse. The creation of the work was supported by Jacob’s Pillow through the Massachusetts Council on the Arts and has been presented at the festival several times.

For more information about the collaboration between Brown and Rauschenberg, explore Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive: Women in Dance essay on Trisha Brown by Maura Keefe.

The convergent histories between dance and the visual arts are extensive, yielding creative collaborations that continue to impress upon artmakers, audiences, and curators alike. For a deeper look into some of these iconic partnerships, see Dance Chronicle’s “Kinetic, Mobile, and Modern: Dance and the Visual Arts.”Meglin, Joellen A., Karen Eliot, and Lynn Matluck Brooks. 2017. “Kinetic, Mobile, and Modern: Dance and the Visual Arts”. Dance Chronicle. 40 (3).

Given the shared creative cross-currents, this essay explores the interplay between dance and the visual arts through a discussion of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival performances taking place between 2002 and 2017. The central works discussed—Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan’s Songs of the Wanderers (1994) and Jonah Bokaer’s CURTAIN (2012)—offer a particular lens to consider the relationship between dance and the visual arts. Each choreography crafts a stage design that incorporates natural elements as transformative agents in the space. Rice. River. Fire. Trees. Sand. These works bring the outside in to create a theatrical environment that makes the architecture stutter. In doing so, they converse with Jacob’s Pillow as a site deeply connected to the history of the land. As you journey through the select choreographies, consider how the interplay between movement and design stimulate the imagination, symbolically offering acts of transformation.

Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan’s Songs of the Wanderers (1994)

Lin Hwai-min, Founder and Artistic Director of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan (hereafter referred to as Cloud Gate), choreographed Songs of the Wanderers after returning from his pilgrimage to Bodhgaya in Northern India, the location where the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama Sakaymuni, achieved enlightenment.Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan. 2002. Songs of the Wanderers. Program. <http://archives.jacobspillow.org/index.php/Detail/objects/45023> The various sections that comprise the evening-length work reveal much about the human condition and essence of life.

In the program note “Journey to Bodhgaya,” Lin recalls his pilgrimage, writing “[o]n the bank of the Neranjra River, I for the first time in my life realized that Buddha was an ordinary mortal who also endured human confusion and struggle.”Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan. 2002. Songs of the Wanderers. Program. <http://archives.jacobspillow.org/index.php/Detail/objects/45023> From this episode in Lin’s life, Songs of the Wanderers was birthed. The choreography theatricalizes quiet moments of reflection obtained by the side of Neranjra River, captures the grandeur of seeing the Mahabodhi Temple for the first time, and remembers meditative states gained under a Bodhi tree. Set designer Austin Wang and props designers Szu Chien-hua and Yang Cheng-yun collaborated with Lin to create visual effects that enliven the stage as the choreographic awakening unfolds. In 2014, Wang was awarded the National Award for Arts, one of the highest artistic achievements bestowed in Taiwan. Tagged the “magician of the theater” by Taiwan Today, he repeatedly establishes atmospheres that transport viewers to alternative realities.Her, Kelly. 2015. “Magician of the Theater.” Taiwan Today. Online. <http://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=20,29,35&post=26520> Together the stage and prop designs play a significant role in enacting the abstract representations of religious rituals present in the work.

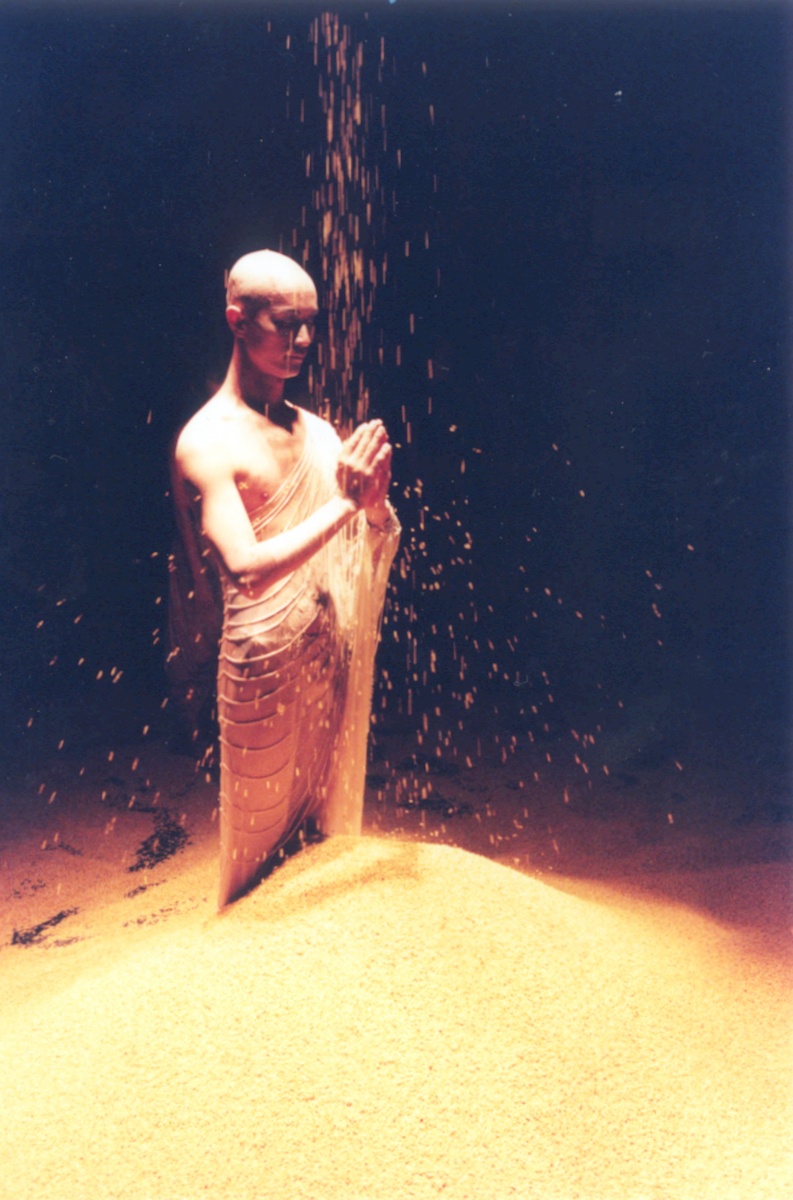

Cloud Gate’s Songs of the Wanderers opens with a lone Buddhist monk standing still under a steady stream of golden colored rice. For nearly 70 minutes, a pool of amber lights bathes Wang Rong-yu—the performer who originated the part of the monk—as grains of rice cascade from the sky, falling upon his head. In an astonishing display of determination and concentration, Rong-yu remains seemingly motionless with hands held in a prayer position, eyes closed, and head slightly lowered. Gradually a mound of rice gathers around his lower body. The spatially isolated narrow stream of rice turns into an aggressive showering that covers every inch of the stage space. In fact, over 500 pounds of rice are used to create shifting landscapes throughout the work, forming mountains, deserts, and rivers through which the dancers enact a spiritual pilgrimage.

Commenting upon the cultural and personal significance of rice, Lin remarks “[r]ice is sacred in Asia. When we were children, rice was everything. Farmers would spread the rice in the courtyard or even on the road to let it dry. It held such a great fascination, but if you were caught playing with it you really got in trouble, because you were ruining the food.”Sims, Caitlin. 2000. “The Serenity Of Meditation On the Move”. New York Times. 150 (51556). Online. <http://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/29/arts/dance-the-serenity-of-meditation-on-the-move.html> In Songs of the Wanderers, the rice remains sacred, but the hesitation to handle it disappears as dancers playfully animate the grains, tossing them into the air in a manner that extends lines of energy infinitely into space. The video clip from Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive below elucidates the powerful partnership between the movement and design elements.

Songs of the Wanderers premiered in Taiwan in 1994 and was performed at Jacob’s Pillow in 2002. Founded in 1973, Cloud Gate is considered Taiwan’s first professional contemporary dance company.

Jonah Bokaer’s CURTAIN (2012)

A fortunate stroke of serendipity brought Jonah Bokaer and Daniel Arsham together. Bokaer, an alumnus of the School at Jacob’s Pillow, is a choreographer and media artist who became the youngest member ever to join the Merce Cunningham Company in 2000. During Bokaer’s seven-year stint with the company, Cunningham invited Arsham to create the stage design for eyeSpace (2007). Arsham would later go on to design for Cunningham’s Tour de Paris and Park Avenue Armory Events. The design for the latter was informed by the former. As audience members entered the cavernous space of the Park Armory’s Drill Hall, they were met with beams of white light that projected upward and fell upon Arsham’s installation looming in the sky; clusters of gray polyethylene balls hung in cloud formations. As described by Ted Loos of the New York Times, “The shape and color of the clouds, which took six months to construct, are based on pixelated photographs of clouds [Arsham] has taken around the world while on tour with the company.”Loos, Ted. 2011. “Cunningham Fostered Serendipity in Set Design.” New York Times, 161 (55634). Online. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/29/arts/dance/daniel-arsham-on-designing-sets-for-merce-cunningham.html> The shared sensibilities forged by these overlapping experiences and common histories, undoubtedly, continue to influence the collaborative partnership between Bokaer and Arsham.

The ghostly presence of Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg, who served as resident designer of the Cunningham Company from 1954-1964, make it impossible to restrain oneself from projecting into the future, prematurely identifying Bokaer and Arsham as among the most influential collaborative partnerships of the twenty-first century. The two began collaborating in 2009 with the work Replica; later creating Why Patterns (2010) and Recess (2010), each having their U.S. premieres at Jacob’s Pillow in 2011. With an interest in the intersect between movement, visual arts, and architecture, this collaborative pair reconfigures theatrical spaces through innovative experimentations with form and matter. For Why Patterns, seen below, the artists incorporate over 10,000 ping-pong balls that pour from above, imposing their own random design onto the work.

For Bokaer, “[t]he act of combining visual arts and dance has initiated [his] entire oeuvre. This is a life-long project which continuously questions and challenges the role of a choreographer’s participation in fine art.”Bokaer, Jonah. <http://jonahbokaer.net/> With CURTAIN, Bokaer and Arsham continue to probe the potential of incorporating fine art and physical objects into choreographic structures.

CURTAIN commences with a curious image—Bokaer stands with his back to the audience opposite a decaying human-sized figure rising out of a sand pile. There is something defiant about Bokaer’s stance. His right arm hangs straight with fist clutched, as his left arm caresses his lower back to grasp the other elbow. Despite the energy of resistance, the movement that unfolds is tender with Bokaer using self-touch to explore the architecture of his body. The atmospheric composition by Chris Garneau lulls the audience into a meditative state as fellow performers James McGinn and Adam H. Weinert enter the space, intriguingly wearing headphones. For fleeting moments, the trio’s movement overlaps and yet they seem to exist in disparate worlds.

Bokaer dispenses a moment of shock when he circles the human-like figure, delivering an aggressive blow which brings the statue to its knees. He assumes the empty void left by the fallen creature. Stepping into the pile of sand, Bokaer once again turns his back to the audience and extends his arms stiffly to the side. A mysterious white substance begins a slow descent from the ceiling. In a review for the Miami Herald, contributor Jordan Levin contemplates this curious moment writing, “CURTAIN sets up all sorts of fascinating questions about the way we define the qualities of things. The white stuff moves, but it’s not alive. Is it fluid or solid? How can it be both?”Levin, Jordan. 2015. “Bokaer and Arsham’s Curtain—Mater meets Movement.” Miami Herald. Online. < http://www.miamiherald.com/entertainment/ent-columns-blogs/jordan-levin/article13023851.html> Throughout its duration, the work encourages spectators to question the relationship between agents—liquid and solid, human and non-human, organic and inorganic—in manners that challenge any clear distinction between perceived dichotomies. Even the dichotomous relationship between nature and culture seems to be challenged as the entirety of this performance event seeps beyond the theater walls after enormous barn doors situated upstage open to the wooded world yonder.

The following clip from Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive captures the quality of contemplation established through Arsham’s design and Bokaer’s movement vocabulary.

Arsham and Bokaer returned to Jacob’s Pillow in 2017 to present their newest work, Rules of the Game (2016). As scholar-in-residence Maura Keefe discusses in the PillowNote for the production, Luigi Pirandello’s 1921 absurdist play Six Characters in Search of an Author inspired this collaboration. An original score by GRAMMY Award-winning artist Pharrell Williams, arranged and co-composed by David Campbell, accompanies the choreography. Bokaer considers his work to be a “cross-over” between dance and the visual arts. With this collaboration, might there also be room to consider a cross-over between the avant-garde and popular?

Outside/In: Four Examples

The Inside/Out performance series at Jacob’s Pillow has a long history of presenting dance against the natural landscape of the Berkshire mountains.

Choreographies like Cloud Gate’s Songs of the Wanderers (1994) and Bokaer’s CURTAIN (2012) offer an inverse to this experience, bringing elements of the outside into the performance space. Both works combine dance and the visual arts through scenography that harkens to life-giving sources. Compagnie Jant-Bi’s Le Coq est Mort (The Rooster is Dead, 1999), Company Wang Ramirez’s Monchichi (2011), LeeSaar The Company’s Grass and Jackals (2013), and MadBoots’ Beau (2015), among other works, join Songs of the Wanderers and CURTAIN through their incorporation of natural elements as transformative agents in the space.

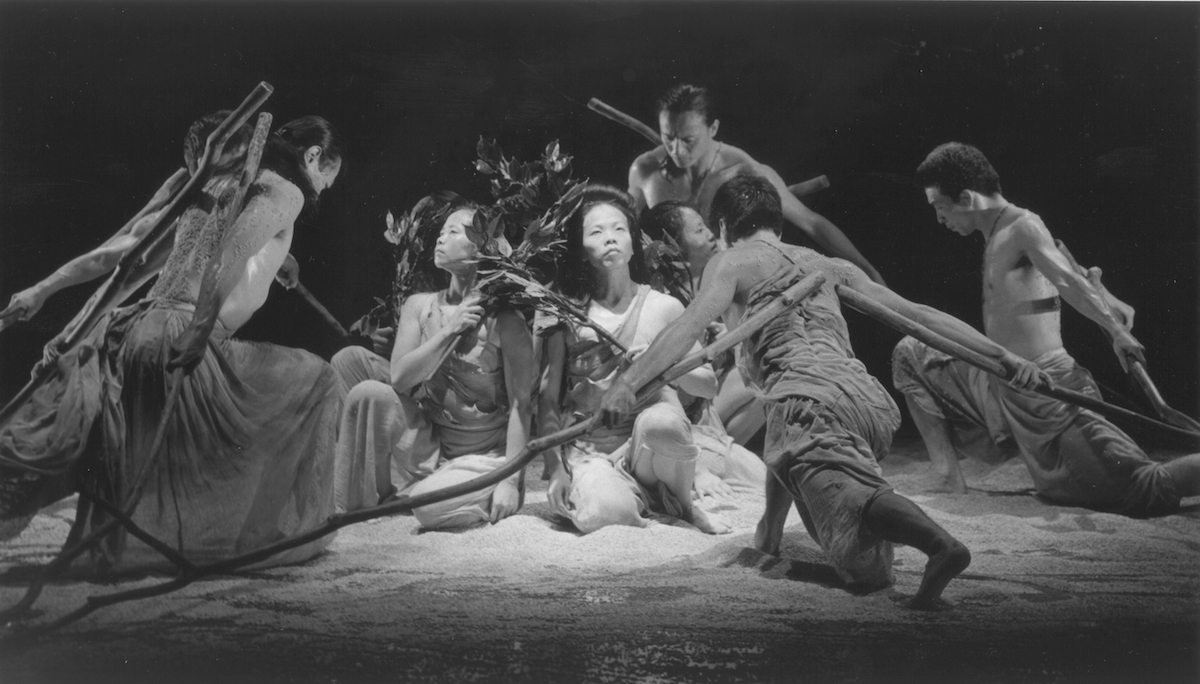

An intercultural collaboration between Germaine Acogny’s Senegal-based company Jant-Bi, German choreographer Susanne Linke and her assistant, Israeli Avi Kaiser, Le Coq est Mort (The Rooster is Dead) fills the stage with sand.

Designer Ida Ravn helps establish the environment for Honji Wang and Sebastian Ramirez’s Monchichi by creating a barren birch tree that the dancers partner with throughout the work.

When asked “What will we see in Grass and Jackals?,” Israeli choreographers Lee Sher and Saar Harari respond stating, “I think life. You know. Our life. Our sensation or wills, or desires.”The Dance Enthusiast: Dance Up Close. 2014. “Grass and Jackals w/ LeeSaar The Company.” Online. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mT2Bky3zA3M> Visions of isolated and lonely creatures resolve in the work’s concluding moments with lighting and stage designer Bambi’s curtain of rain.

Choreographers Jonathan Campbell and Austin Diaz’s MadBoots stages “[m]an’s alienation from the sources of life—nature, earth, water—[as] an analogy for his alienation from his own physicality” in the work BEAU.MadBoots. 2015. BEAU. Program. <http://archives.jacobspillow.org/index.php/Detail/objects/53997> A neatly assembled arrangement of fallen flowers contained within the confines of a square box outlined on the floor slowly exceeds their boundaries in a gesture of sweet release.

Conclusion

Choreographies that use space in unconventional ways, in these instances by opening the theater to the outside, not only make the architecture stutter, they cause all those contained within it to stutter too. Following philosopher and scholar Elizabeth Grosz, these dances ask: “What is it to open up architecture to thought, to force, to life, to the outside?”Grosz, Elizabeth A. 2001. Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. In these choreographies, the partnership between dance and the visual arts renders visible energetic forces that bodies and environments possess, highlighting the transformative capacities of each.

PUBLISHED April 2019