The Summer of 1940

From 1933-1939 Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers had spent each summer at Jacob’s Pillow rehearsing, performing, creating new works, and preparing for upcoming tours. But by the late spring 1940 the company had closed, and Shawn put “The Farm,” as Jacob’s Pillow was informally known, on the market.Norton Owen, A Certain Place, 11.

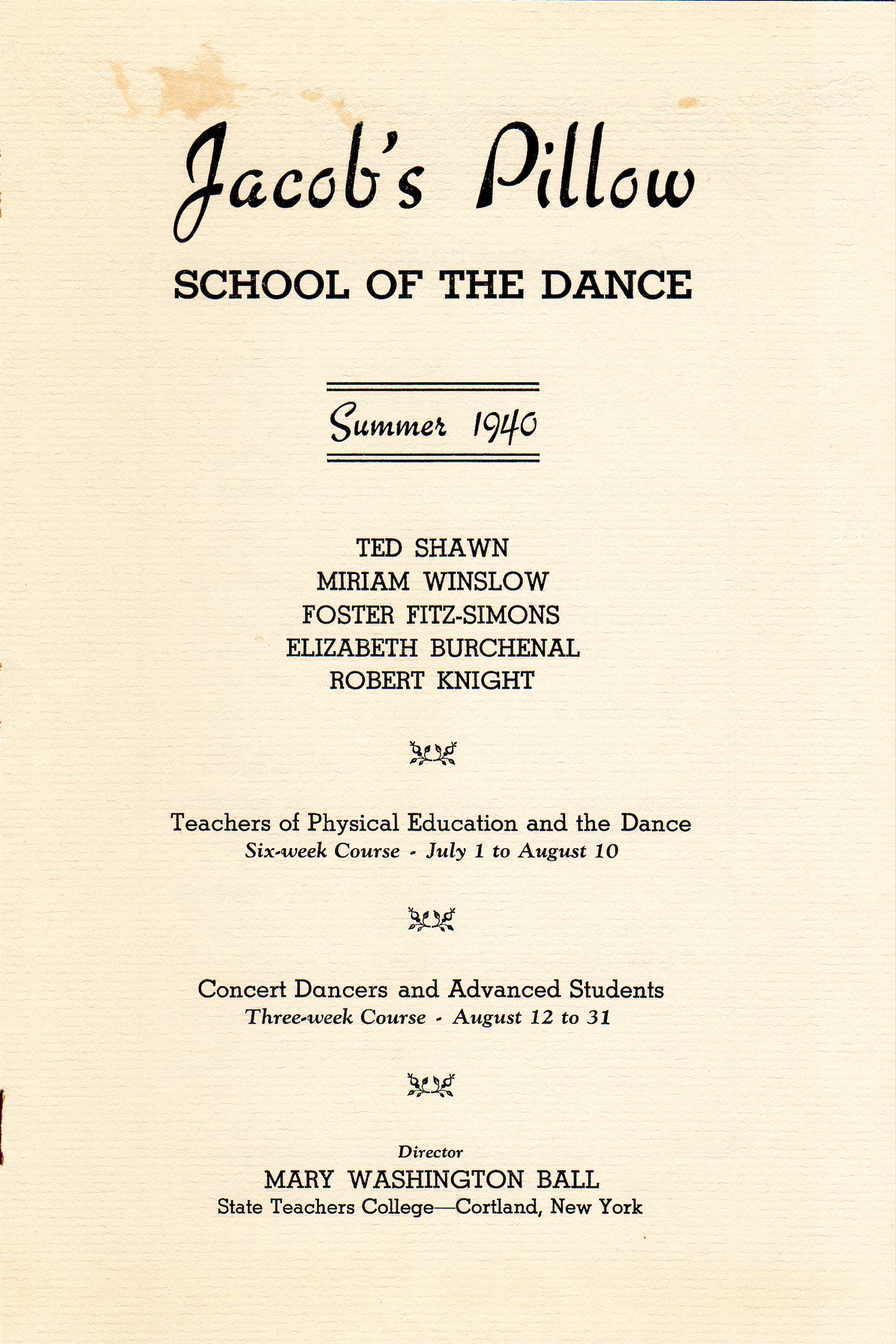

Shawn leased the property with an option to buy, for the summer of 1940, to Mary Washington Ball, an associate professor in physical education at the Cortland Normal School in upstate New York. Ball ran The Jacob’s Pillow School of Dance and The Berkshire Hills Dance Festival. The festival was modelled after Shawn’s lecture-demonstrations and was held each Saturday afternoon with tea. Jacob’s Pillow School of Dance, 1940 program, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

The festival included demonstrations of Ballet, Ballroom, and Concert Dance as well as performances by dancers including Shawn himself, Le Meri, former Men Dancer Foster Fitz-Simons and his dance partner Miriam Winslow, Barton Mumaw, and Ruth St. Denis. The final lecture-demonstration was a performance by Shawn and the Men Dancers entitled Home-coming. This performance included the whole Men Dancers group, except for John and Frank Delmar, and was the last performance by the company.Ted Shawn, How Beautiful Upon the Mountain: A History of Jacob’s Pillow

The school ran two courses. The first six-week course was advertised as for Teachers of Physical Education and the Dance. The second three-week course was for Concert Dancers and Advanced Students. The teaching staff included Shawn and Foster Fitz-Simons among others.

The festival and school were an artistic success, but a financial disaster, and Ball was unable to buy the property as hoped. Disheartened, Shawn was forced to re-list Jacob’s Pillow for sale after the 1940 season.

1941 – A new beginning

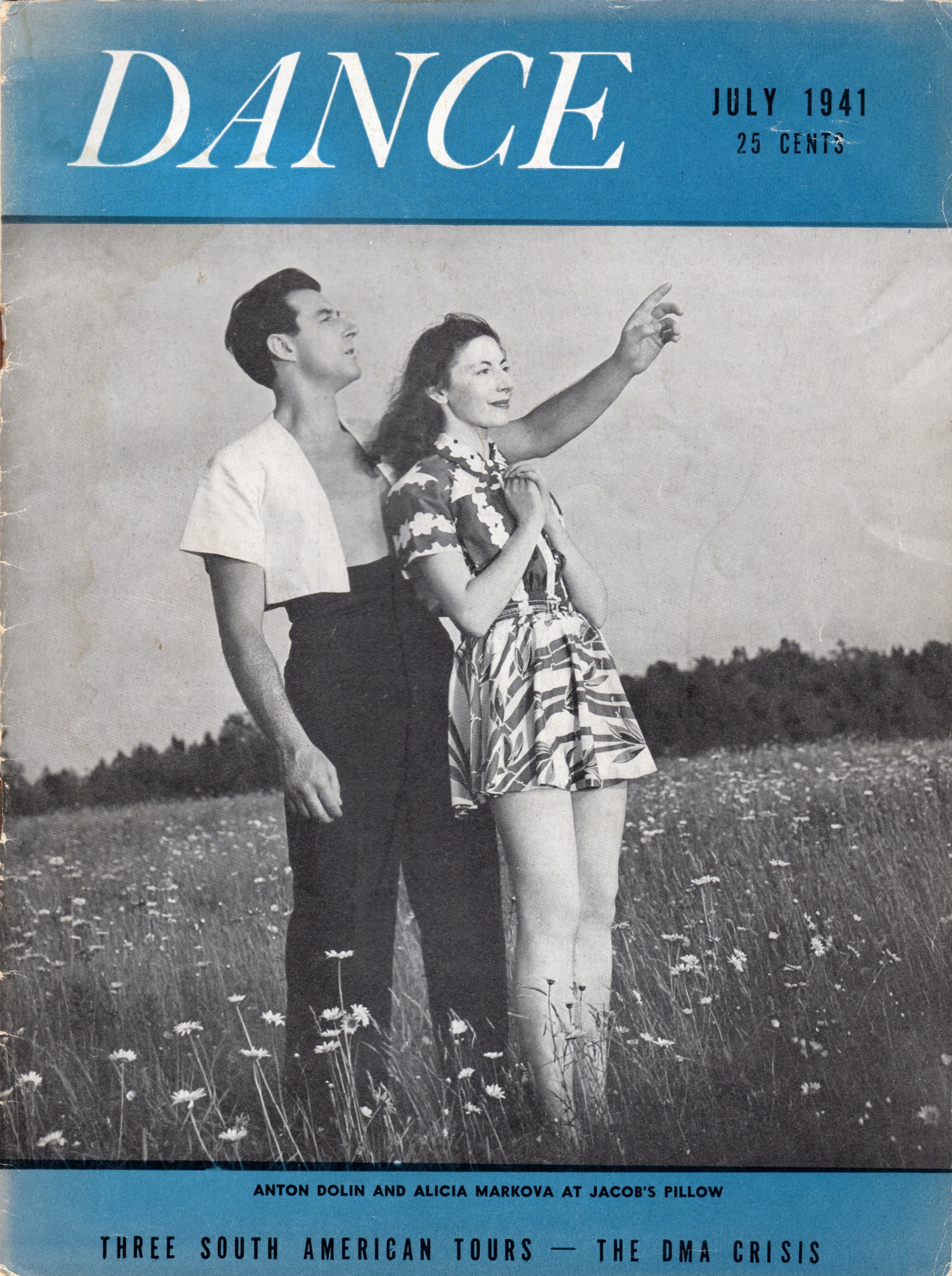

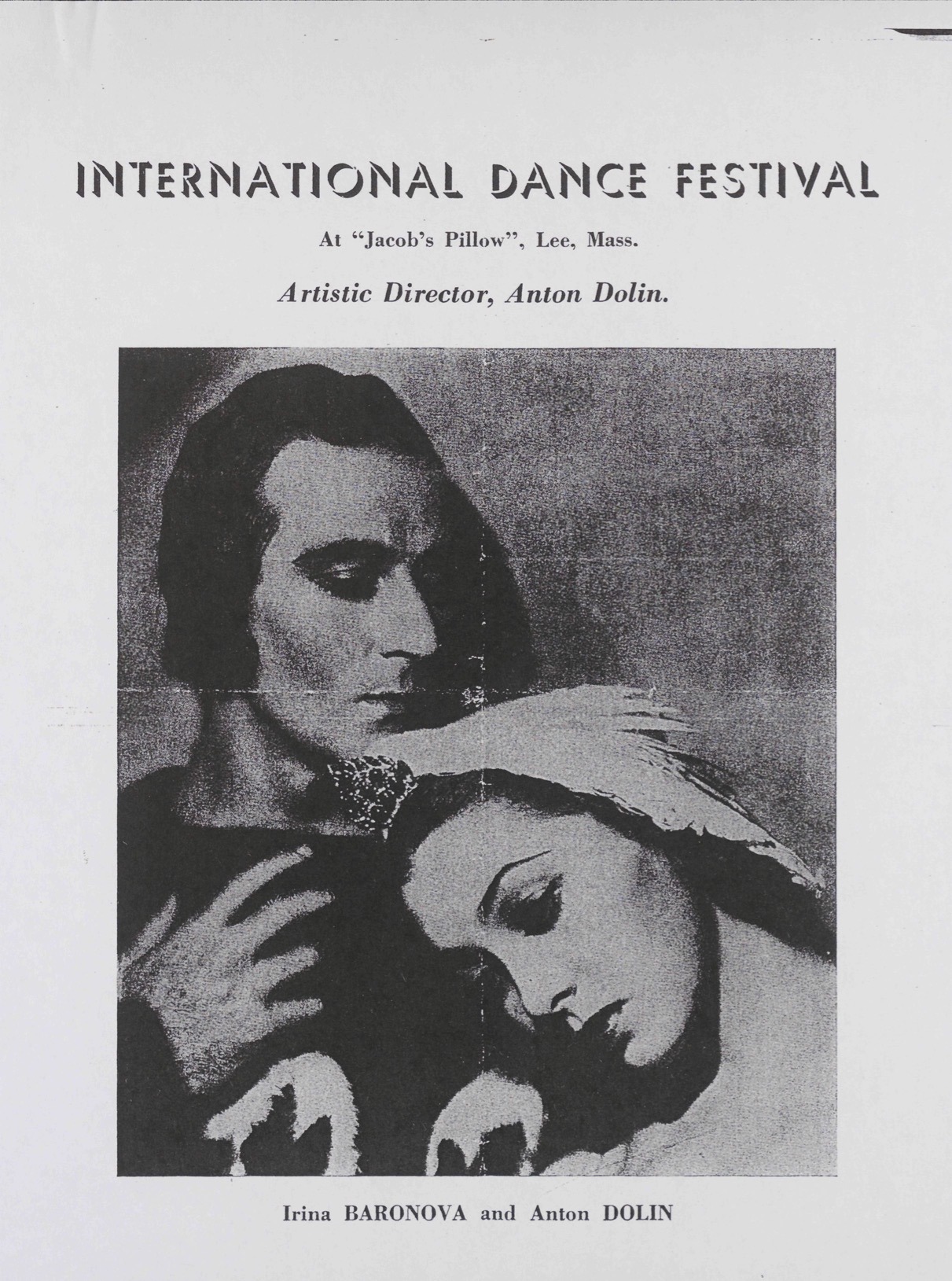

It was two British ballet dancers who brought Jacob’s Pillow back to life in 1941. Anton Dolin (1904–1983) and Alicia Markova (1910–2004) were ballet superstars. They had both danced with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and had appeared together as guests for many companies before forming The Markova-Dolin company in the mid-1930s. By the late 1930s, with World War II raging in Europe, they were both working in the USA. In 1941, Dolin was working as a dancer and choreographer for the newly formed Ballet Theatre (which would later become American Ballet Theatre) and Markova was a principal dancer with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Dolin knew that Markova’s contract with The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo would be up soon and persuaded her and several other dancers from the company to join Ballet Theatre. However, a problem soon arose. The company was about to go on an unpaid summer break and the dancers would scatter until the company resumed operations in the fall. Dolin wanted to find a way to keep the company and its new dancers together.

Dolin knew Shawn and thought that perhaps that “The Farm” might offer a solution. Dolin later wrote:

Ted was willing, quite anxious, to let me have Jacob’s Pillow for the summer at a rental of 1,500 dollars. I motored down with him… and fell in love with it at once. I felt that if I could get it, it would be a haven for Alicia and me. We could work, teach, perhaps give a few dance recitals; anyhow, we could lie there for a while.

The property was leased for the couple by a benefactor and friend, Florida-based British millionaire Reginald Wright.

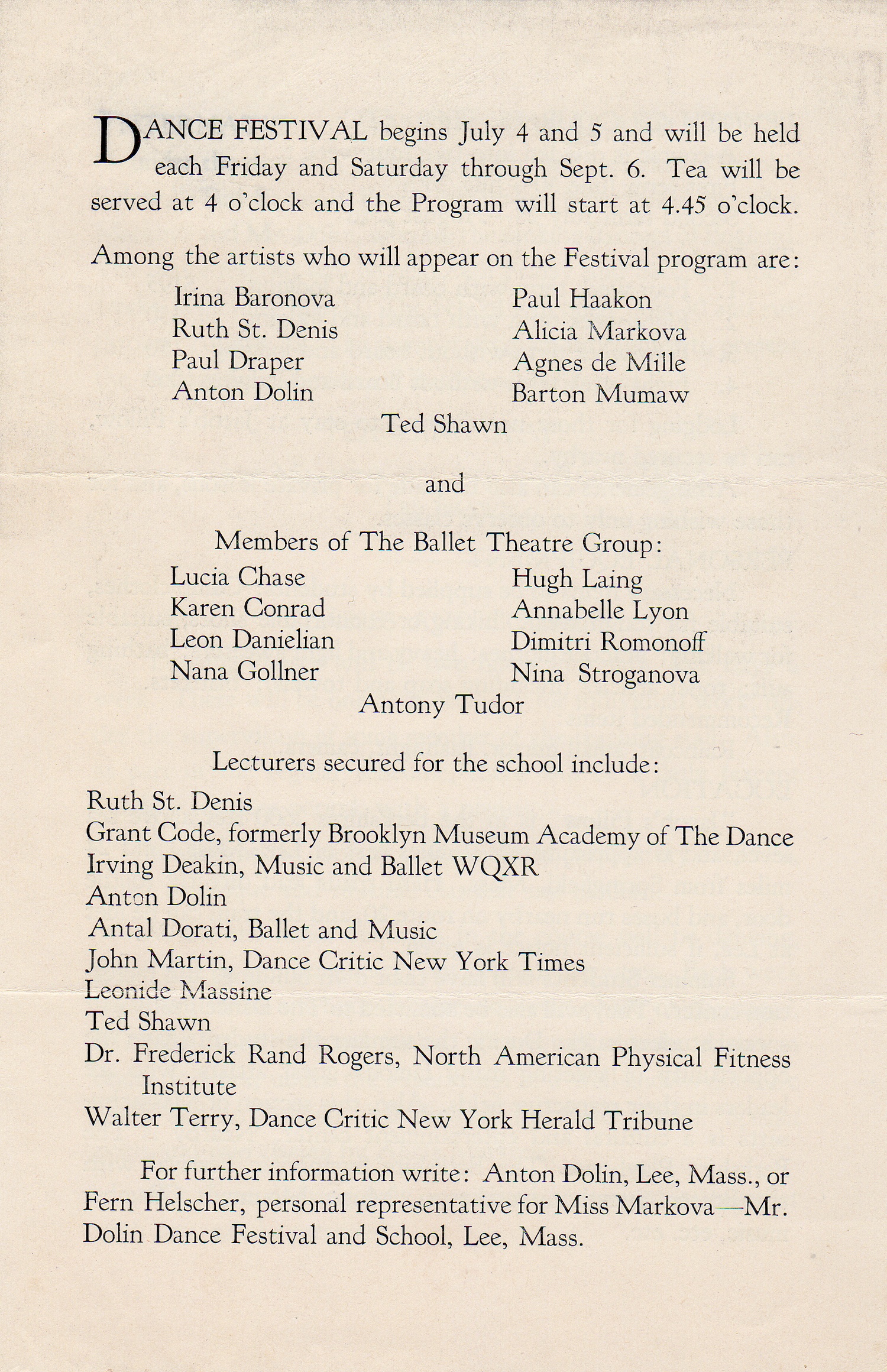

So in the summer of 1941 the ballet came to Jacob’s Pillow. Around 20+ dancers from Ballet Theatre spent the summer in the Berkshires, with others just stopping by for a couple of weeks or just a few days.Markova stated it was up to 30 dancers. The dancers were a mix of British, Russian and American and included some of biggest names in ballet at the time: Markova and Dolin, Russian “Baby Ballerina” Irina Baronova, American dancer and founder of Ballet Theatre Lucia Chase; fellow American dancers Nora Kaye, Nana Gollner, Annabelle Lyon, Maria Karniloff (Karnilova), Donald Saddler, Leon Danielian, and Dwight Godwin; Russian dancers Katherine Sergava, George Skibine, and Dimitri Romanoff; and British dancers Hugh Laing and Antony Tudor—as well as others.This list consists of the most prominent dancers whose presence has been confirmed. Among the visitors who came and went were Frederic Franklin and Agnes de Mille.

Choreographers Dolin and Tudor worked with the dancers on staging works and creating new pieces including Tudor’s Pillar of Fire which premièred the following year. In August the legendary Bronislava Nijinska, former Ballets Russes dancer, choreographer and sister of Vaslav Nijinsky, arrived to rehearse The Beloved and stage a number of other pieces.

Irina Baronova later recalled: “We rehearsed very intensely with Dolin, Tudor and, and upon her arrival, Mme Nijinska, who choregraphed my role, Lise, in La Fille mal gardeé.”Irina Baronova, Irina: Ballet, Life and Love (University Press Florida: 2005), 326.

The International Dance Festival

To keep the dancers motivated and generate income Dolin and Markova announced that they would run The International Dance Festival. The Festival ran for nine weeks on Friday and Saturday afternoons.It was at first advertised as for eight weeks but was increased to nine. The New York Times reported that: “In the tradition of the place, and certainly without violation of the English dancers’ tradition, there will be tea at 4, and the performance, beginning at 4.45, will run to 6.”The New York Times, Sunday May 4, 1941.

The performances were given in the converted barn studio previously used by the Men Dancers. Norton Owen writes that the “new directors tried to make the space more theatrical by hanging heavy draperies over the windows and door, adding a front curtain and full theatre lighting.”Norton Owen, A Certain Place, 12. The performers and audience were on the same level making it hard to see and the space become very hot and stuffy.

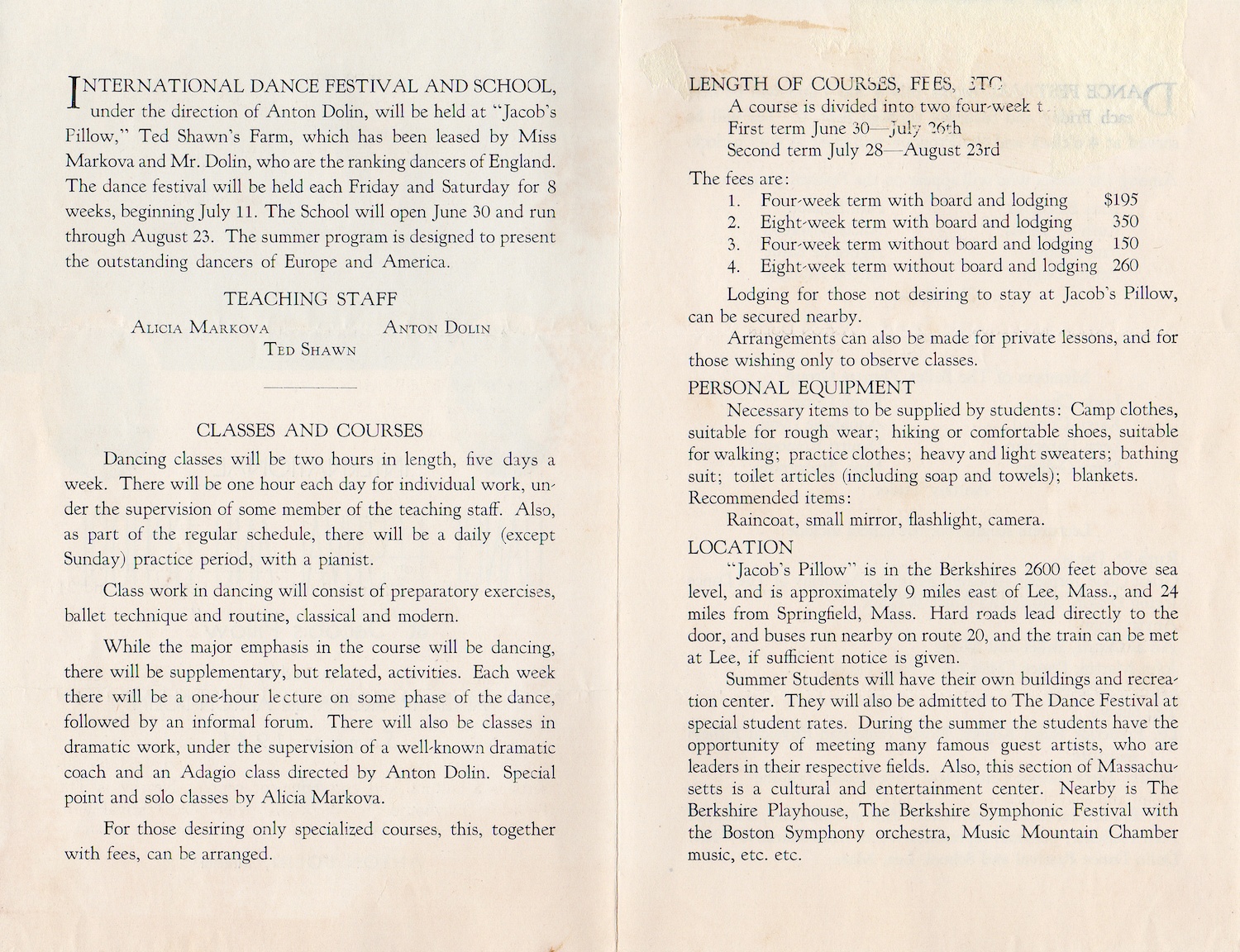

The Festival was advertised as presenting “the outstanding dancers of Europe and America” and not just Ballet Theatre.1941 School and Festival Program, The Jacob’s Pillow Archives. The 1941 International Dance Festival included Ballet, Modern Dance, Tap, and Traditional Dance styles paving the way for the range of genres performed at the Festival to this day.

The Festival brought visitors from far and wide including dance writers and critics Walter Terry and John Martin, both of whom gave lectures as well as reviewing the performance. Joseph Pilates visited, as did renowned costumier Barbara Karinska, who made a number of costumes for the company, and photographers John Lindquist and Hans Knopf documented the events.

The School at Jacob’s Pillow

As well as the festival, Markova and Dolin ran The School at Jacob’s Pillow. The School accepted approximately 20 students who took daily dance classes, sometimes joining the company class, as well as lectures and workshops. Markova, Dolin, and Shawn were listed as teaching staff. The students also helped backstage with the performances.

The students could register for four or eight weeks. Four weeks cost $150 or with board and lodging cost $195. Eight weeks cost $260 or with board and lodging cost $350.

"A Summer of Heart-aches, Bills, Works, Lessons, Rehearsals and Headaches"

Despite the Festival and the School there was little or no money. The majority of the Ballet Theatre dancers took unemployment, which was $10 a week, and contributed $1 a day to Dolin and Markova for lodging and board. In his autobiography, Dolin called it “a summer of heart-aches, bills, works, lessons, rehearsals and headaches.”Anton Dolin, Autobiography (London: Oldbourne, 1960), 120.

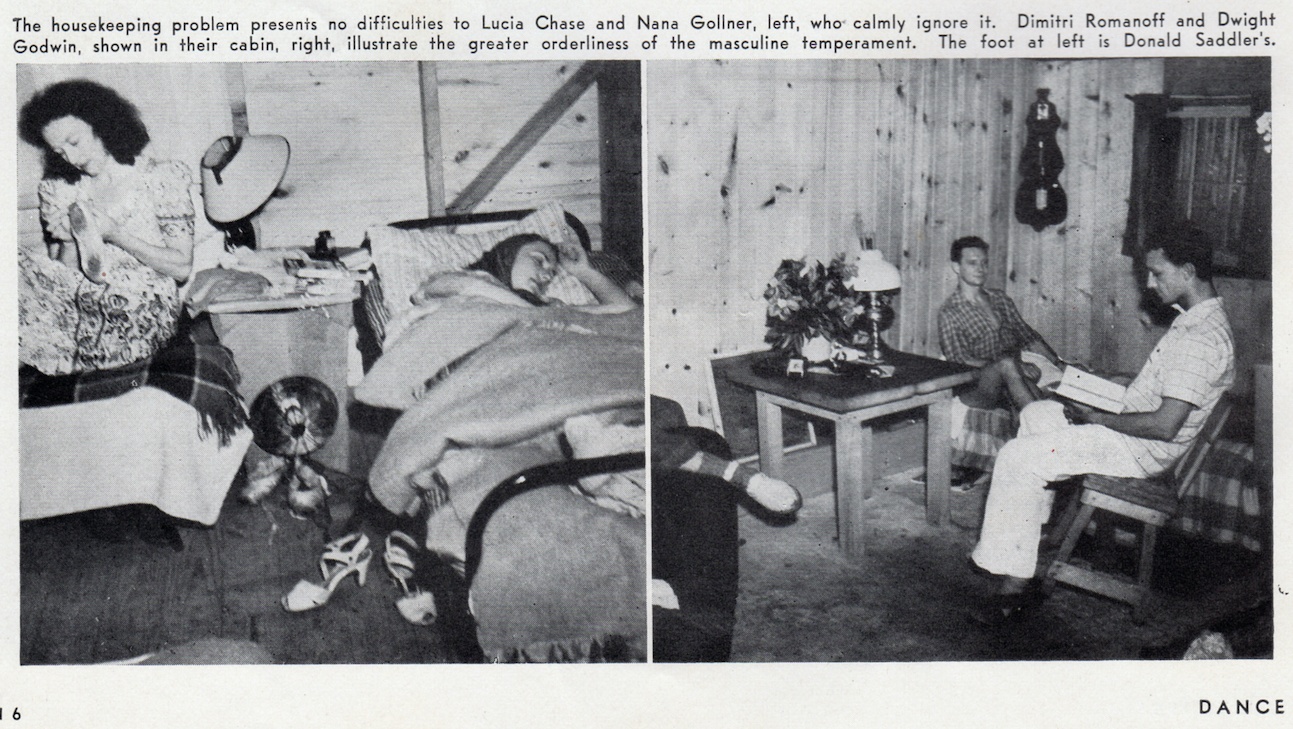

Some of the dancers stayed in the cabins built by the Men Dancers and in the barn above the office (what is The Pillow Store today) and others were lodged locally. Nijinska her husband stayed in a local hotel and brought to the Pillow by car each day.Irina Baronova, Irina: Ballet, Life and Love (University Press Florida: 2005), 327.

Baronova and her husband and Ballet Theatre Director Gerry Sevastianov together with Tudor and Hugh Laing all stayed at Derby House just down the road from “The Farm.” Derby House is now owned by Jacob’s Pillow and continues to house artists today. Baronova wrote in her memoir: “Mother Derby was quite a character – she reminded me of those cosy-looking grannies in children’s books. She fed us well and we abided by her strict rules … It was an idyllic place to work, surrounded by countryside and well away from the city. We all lived as if in a commune, taking turns at daily chores and having great fun.”Baronova, Irina, 326-327.

Markova stayed in what had been Shawn’s bedroom in the main white farmhouse (now known as Hunter House). In an interview she later stated: “I loved that room and made it like a country cottage. When I knew I was going to be there for three months I went off to New York and bought some lovely flowered curtains and a large pink rug because there were only polished bare boards. I also bought a little dressing table and a great pink eiderdown for the four-poster… I had my practice tutus hanging all round the walls.”Maurice Leonard, Markova the Legend, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995), 216-217.

Shawn was apparently not too thrilled about the transformation of his bedroom.

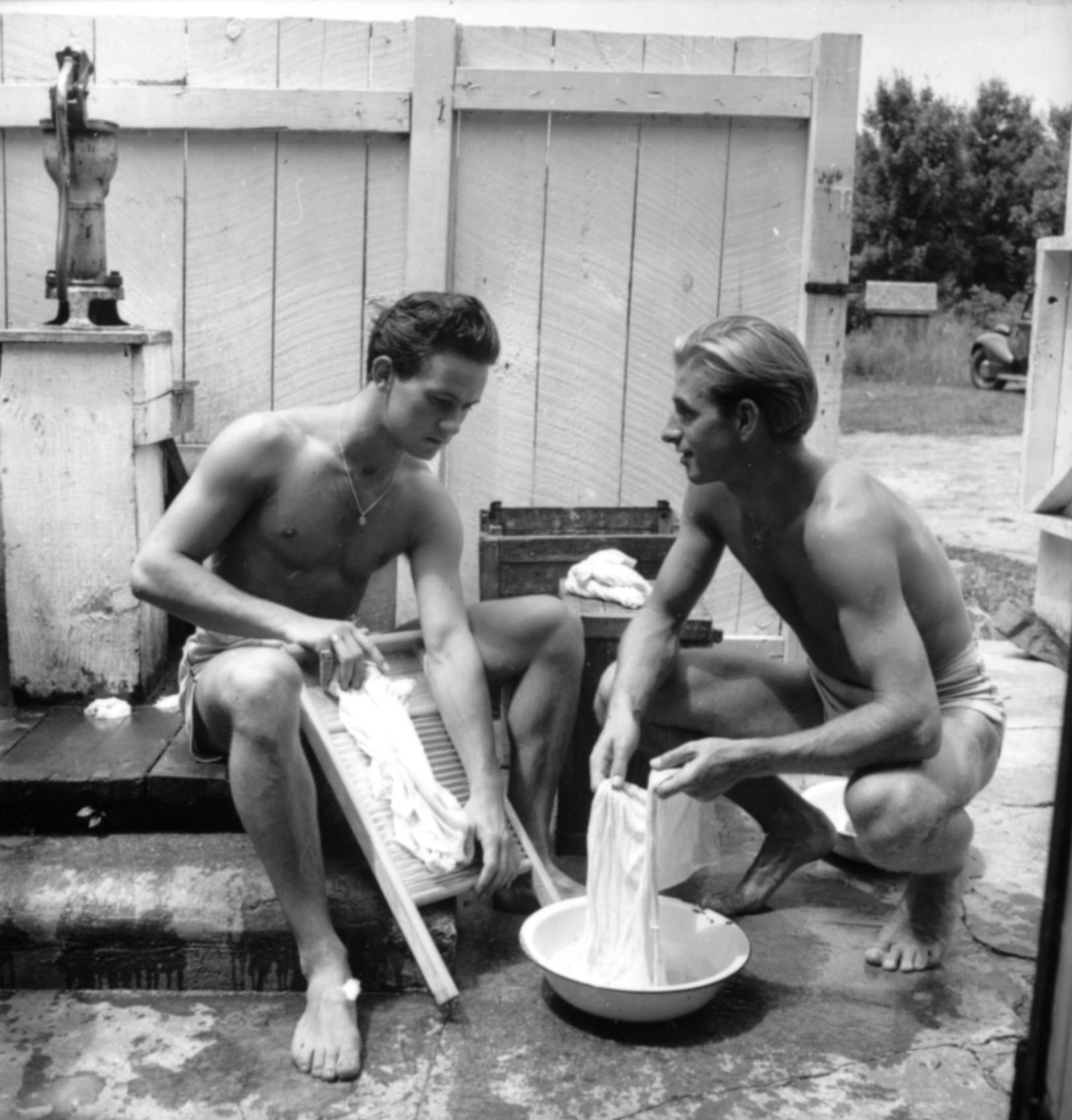

In 1941 the Pillow still had no running water. Markova, determined to make the best of the situation, went to a camping shop in New York City and bought a rubber camping bath that folded up in a zipper bag. “I could stand in it and fill it with water and get my sponge and do what I could,” she later recalled.Maurice Leonard, Markova the Legend, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995), 217.

Much like today, the dancers and students all ate together in the Stone Dining Room, which had been built by the Men Dancers. Markova was in charge of planning meals and making the limited funds stretch each week. Each Sunday, however, Markova and Dolin held an “open house” providing a traditional British Sunday Roast for, as Markova recalled, the “dancers, students, journalists and well-wishers who came to see this extraordinary new community.”Alicia Markova, Markova Remembers, (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1986), 94.

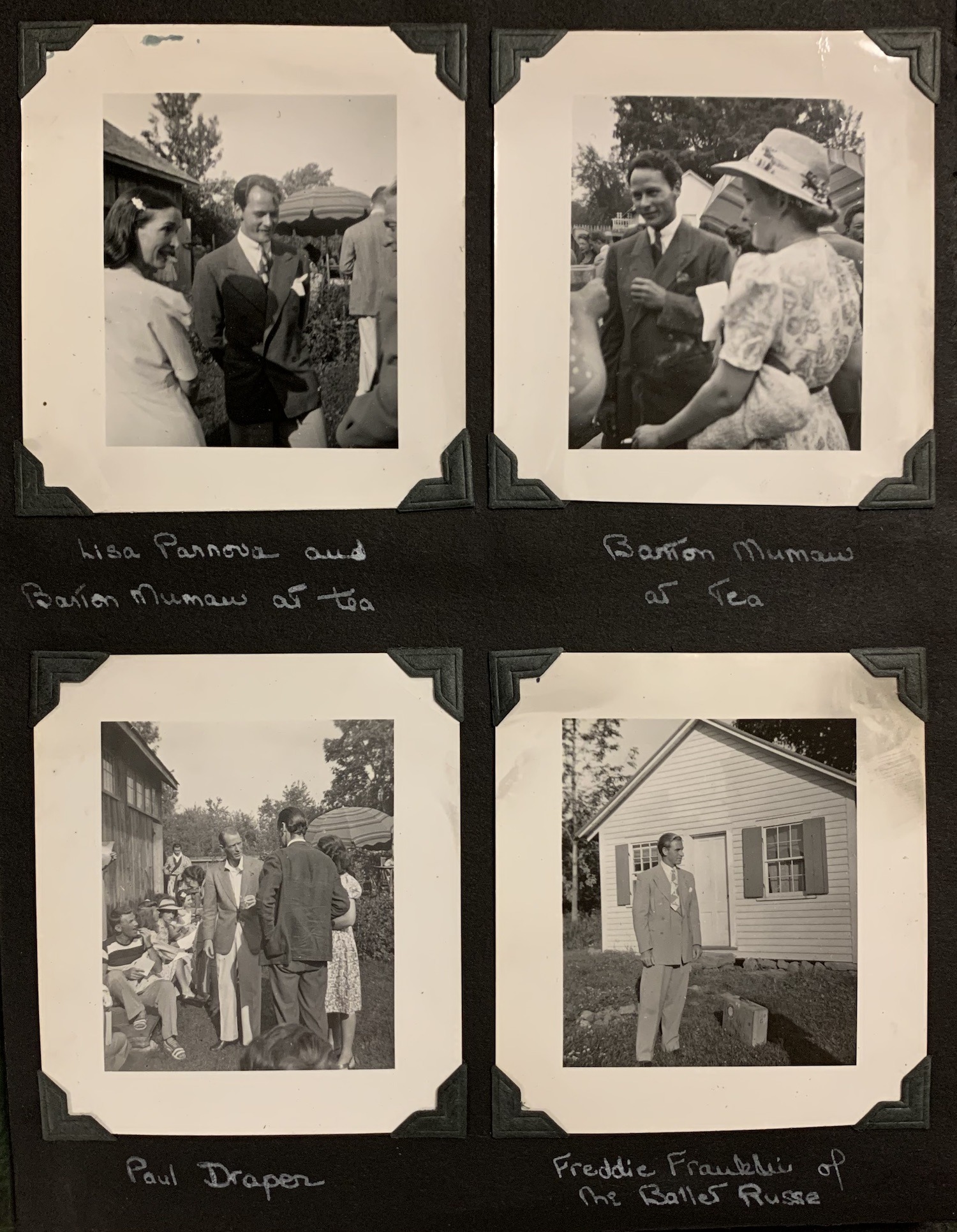

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo dancer and friend of Markova and Dolin, Frederic Franklin, was performing in New York City and came to visit one weekend.

The students were housed at a property further up George Carter Road which also had a studio (this was later moved to Jacob’s Pillow main campus and is now known as Sommers Studio). Ann Hutchinson Guest (b. 1918), was a student that summer and recalled that the “sleeping quarters were in a huge barn called The Ark, in which partitions produced cubby-holes for each student. We had an iron cot, a chair and chest of drawers… Breakfast was provided at the house where one of the staff kept an eye on us. Milk and butter were kept down the well just outside. Water was drawn from this well for washing in basins. The two-seater outhouse nearby served our other needs.”Ann Hutchinson Guest, unpublished memoir.

The Festival—WEEK ONE: July 11-12

The festival was opened by Ruth St. Denis, then in her early 60s. Dolin later wrote “I had the idea of asking Ruth St. Denis to open the Festival and re-create the performance which she had first given in New York.”Anton Dolin, Autobiography, (London: Oldbourne, 1960), 122. St. Denis performed Incense, Cobras, Nautch, Yogi and Radha. Radha was revived especially for the Festival and eight students and dancers from Ballet Theatre appeared as the Priests and High Priests. Here we see an excerpt of Radha filmed by dancer Dwight Godwin.

Former Denishawn dancers Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Pauline Lawrence drove to the Pillow to support Miss Ruth.

WEEK TWO: July 18-19

On the second weekend of the Festival, Markova, Dolin and Ballet Theatre presented a program entitled The Age of Romantic Ballet. This included a pas de deux from La Sylphide performed by Markova and Dolin and Dolin’s Pas de Quatre.

Pas de Quarte had first been created in 1845 to showcase the talents of four of the greatest ballerinas of the time, Marie Taglioni, Carlotta Grisi, Lucile Grahn, and Fanny Cerrito. The works had been recreated in 1936 by Keith Lester for the Markova-Dolin company and, in early 1941, Dolin had decided to restage the work for Ballet Theatre. He wrote to Lester for the choreographic notes, but they were detained by the War Customs authorities, as they were thought to be a coded message.Anton Dolin, Autobiography, (London: Oldbourne, 1960) Dolin therefore created his own choreography for the piece. Markova would become famed for her portrayal of Taglioni and made her debut in this role at Jacob’s Pillow.

WEEK THREE: July 25-26

The third week was a showcase of Shawn’s solo work including The Cosmic Dance of Siva, Four Dances Based on American Folk Music, Flamenco Dances, Chlamys Dance, The Divine Idiot, The Mevlevi Dervish and Invocation to the Thunderbird.

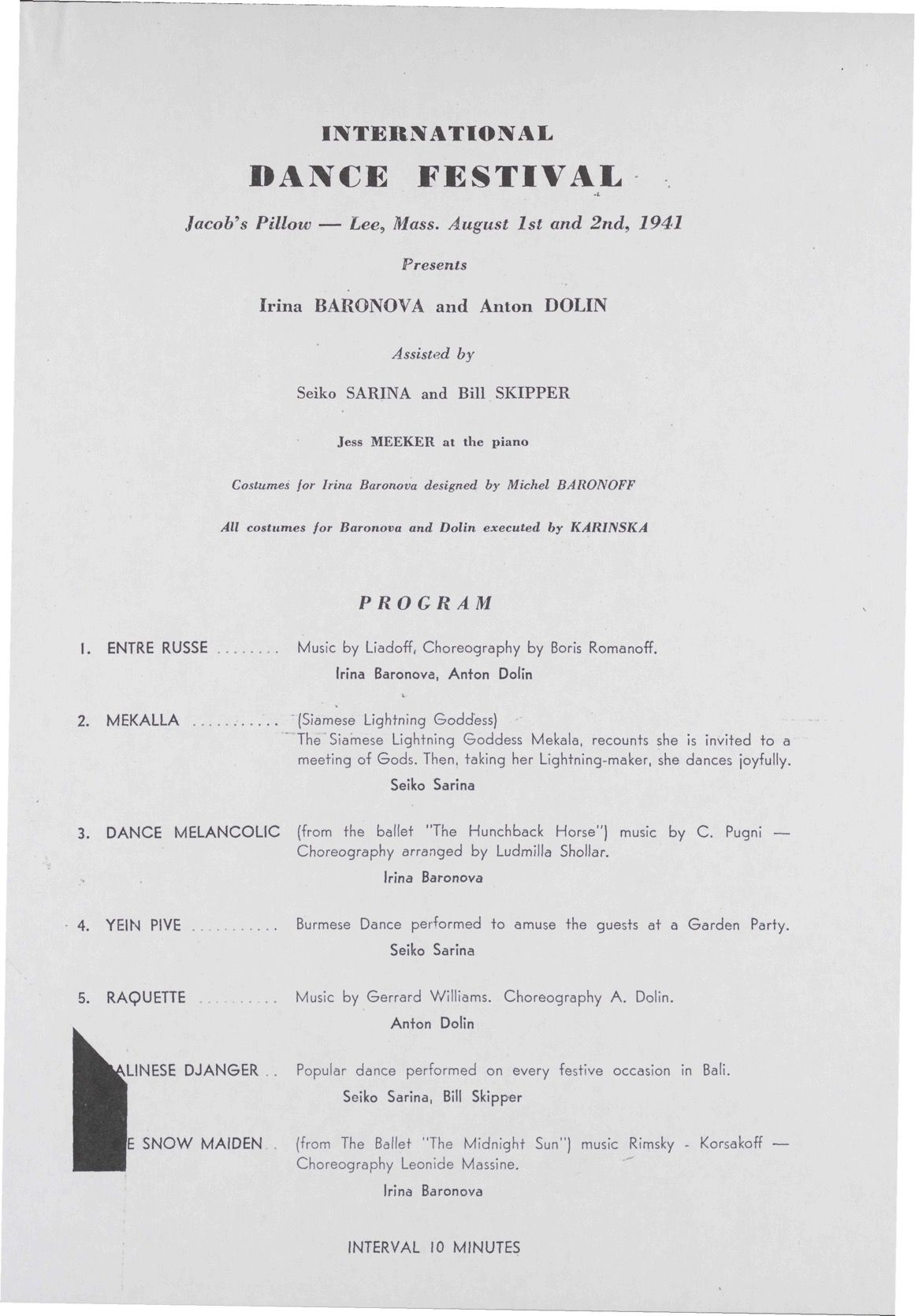

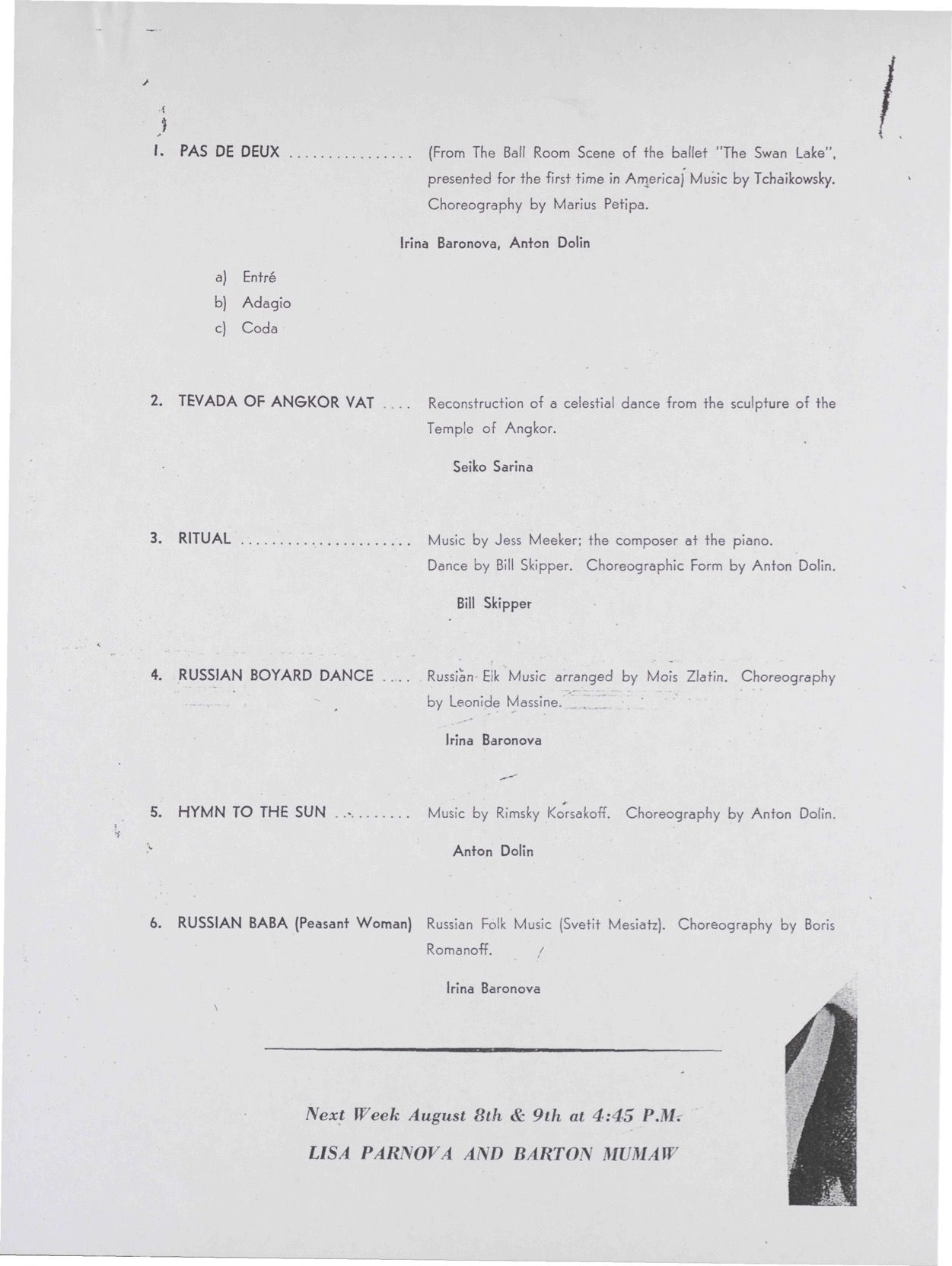

WEEK FOUR: August 1-2

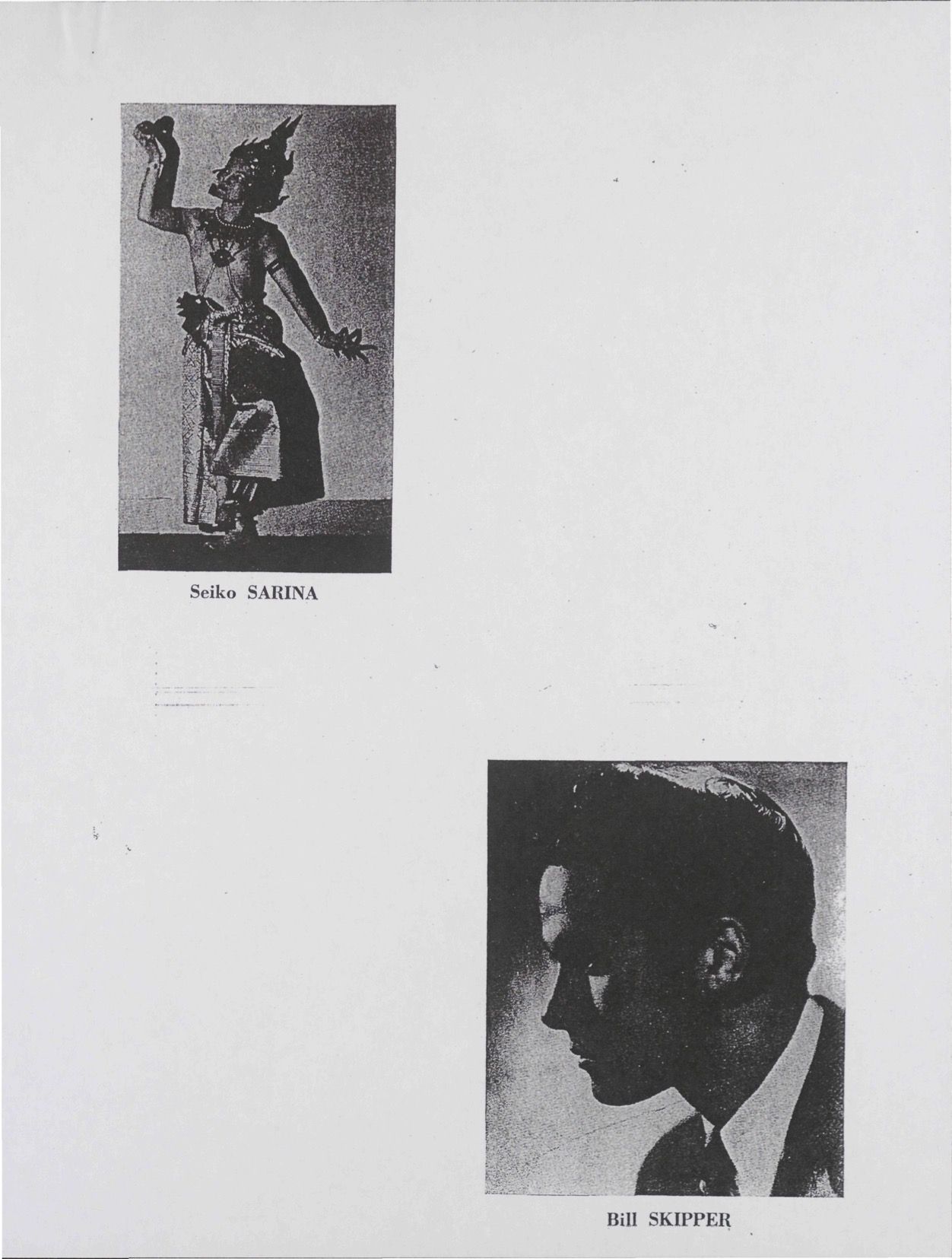

The fourth weekend saw a program of dances by Baronova and Dolin and Indonesian dancer Seiko Sarina. They were supported by scholarship student Billy Skipper.

Baronova and Dolin’s repertoire included solos and pas de deux from works including Swan Lake, The Midnight Sun and The Little Hunchback Horse (although misidentified in the running sheet as “The Hunchback House”) as well as several Russian dances. Sarina performed a series of East Asian dances including a Balinese Djanger with Skipper.

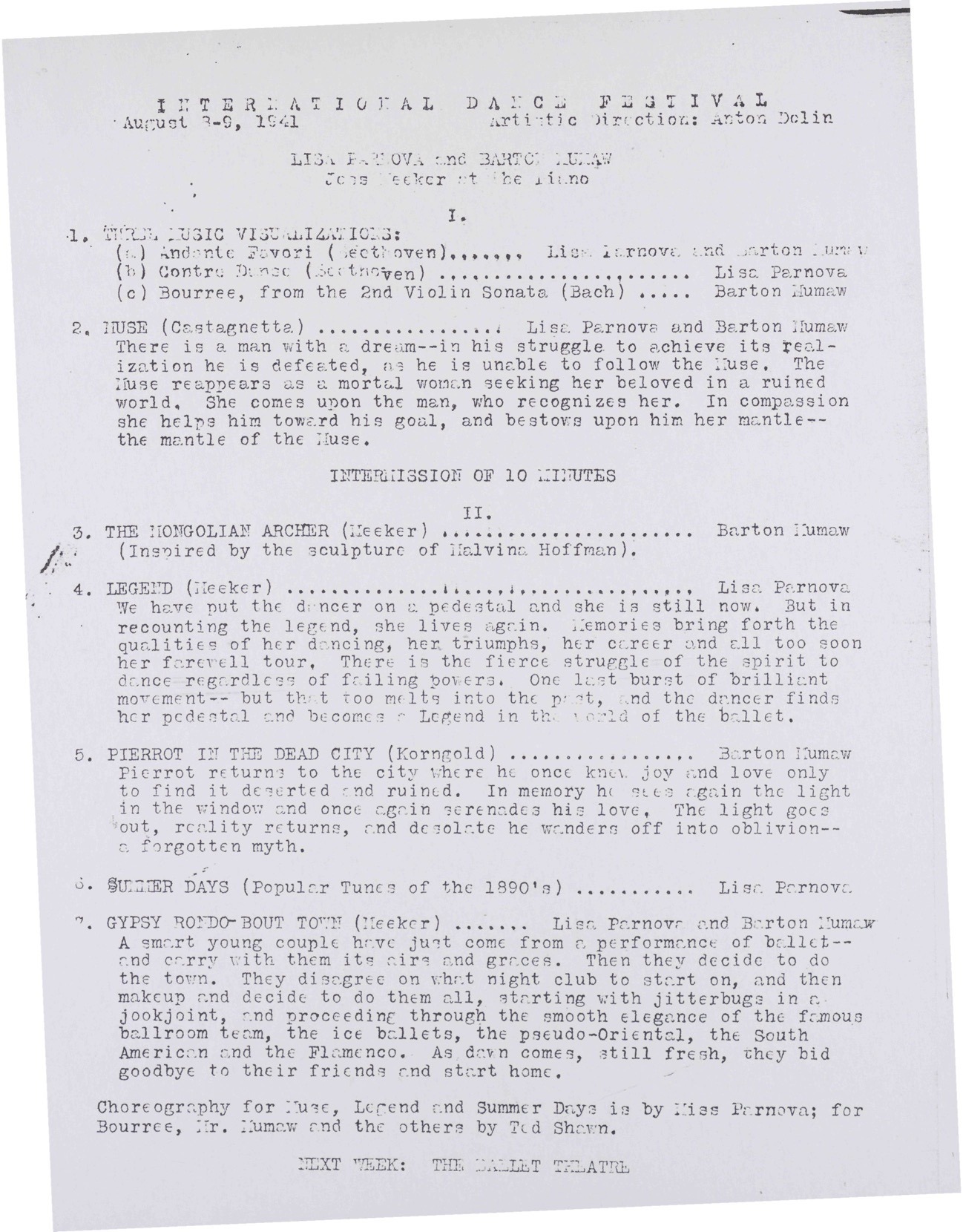

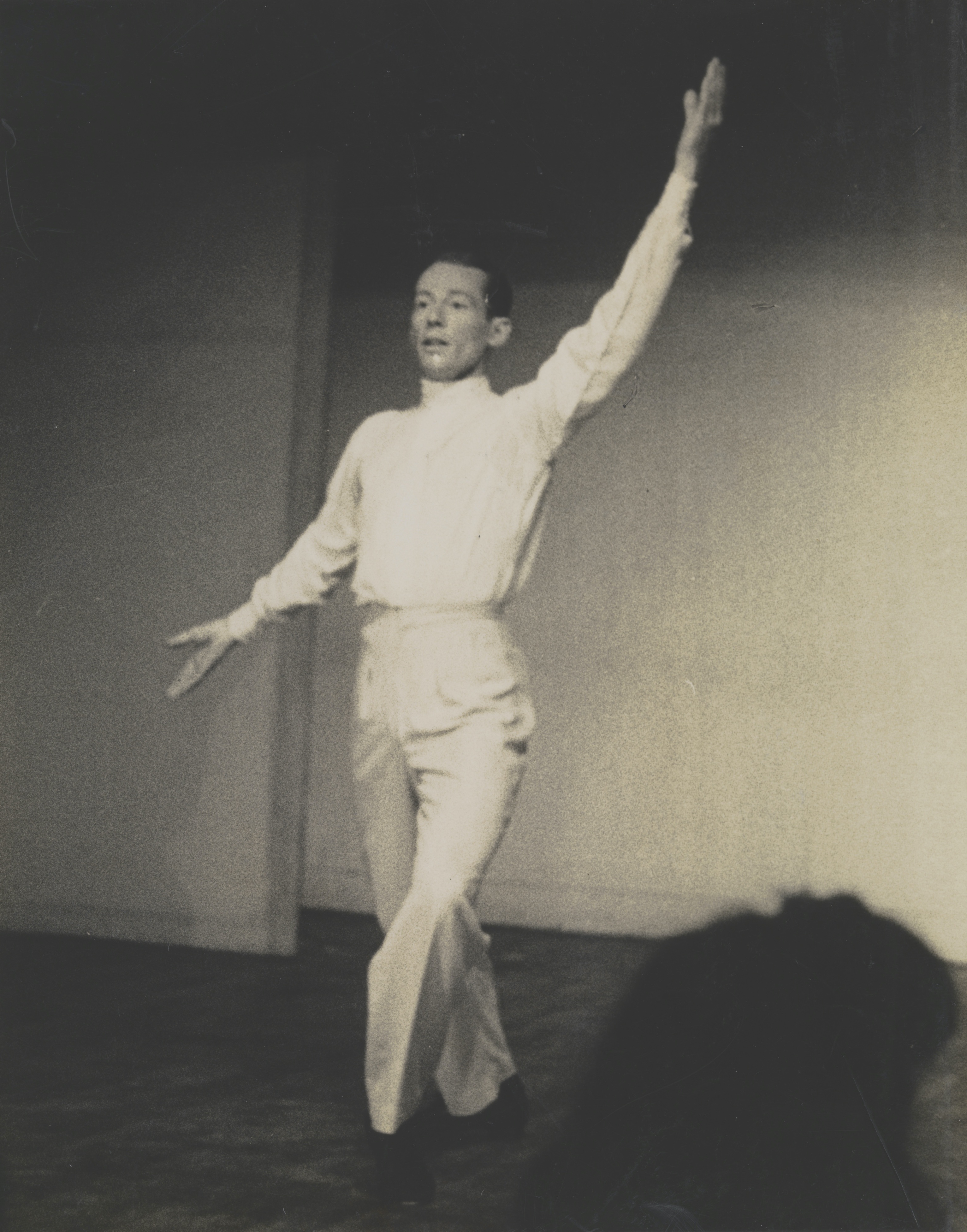

WEEK FIVE: August 8-9

Week five was a program of solos and duets by former Men Dancer Barton Mumaw and his dance partner Lisa Parnova.

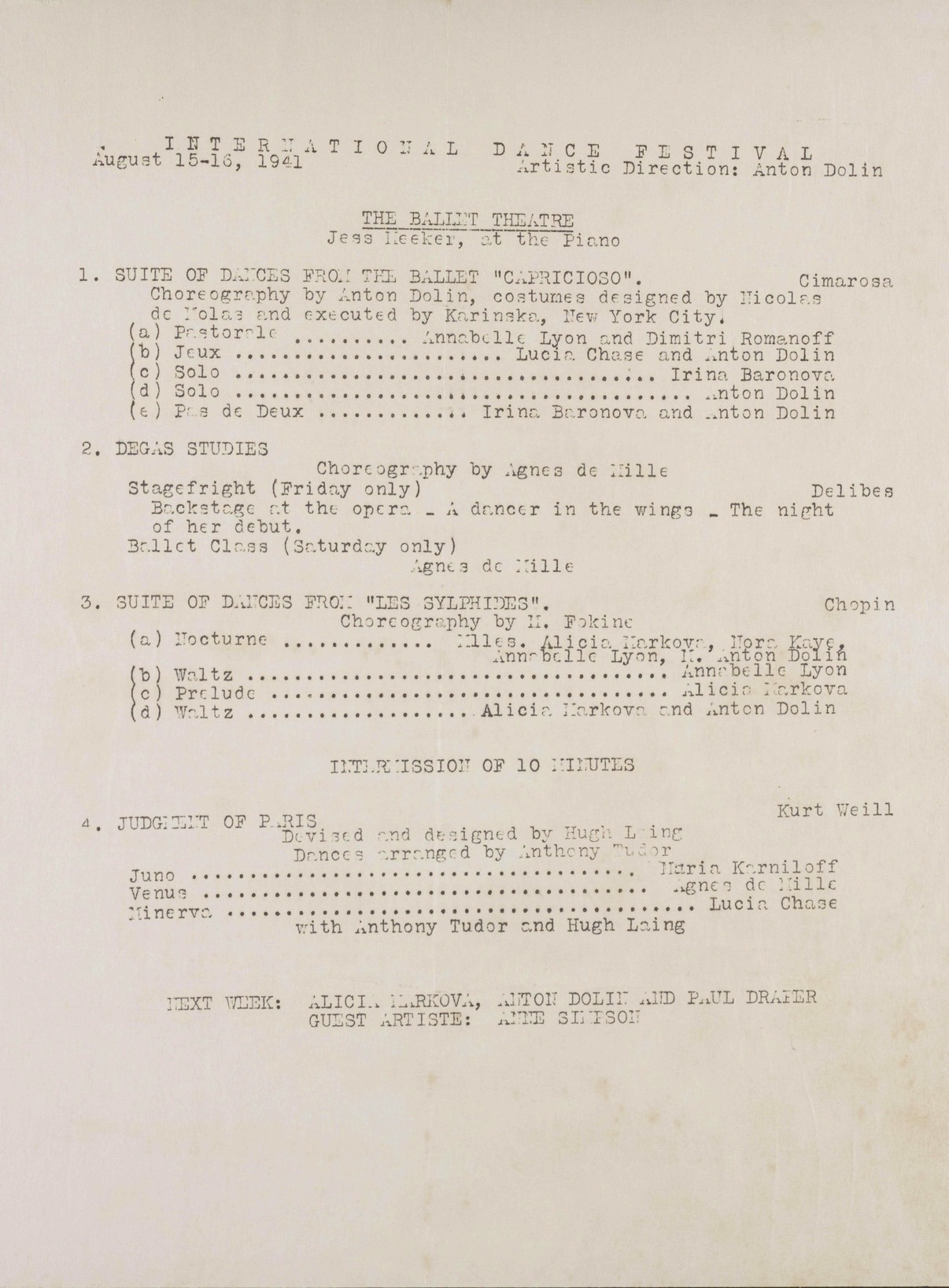

WEEK SIX: August 15-16

Week six was a full program by the dancers from Ballet Theatre including a guest appearance by Agnes de Mille. The program included Dolin’s Capricioso, Fokine’s Les Sylphides and Tudor’s Judgment of Paris. De Mille performed the work Stage Fright on Friday and Ballet Class on Saturday.

WEEK SEVEN: August 22-23

Week seven was a mixed program with Markova, Dolin, Anne Simpson, and tap dancer Paul Draper.

No printed program survives from this week but we know from Donald Saddler’s Daybook that Markova performed the Rose Adagio from The Sleeping Beauty, with Dolin and Saddler as two of the four princes. Saddler described this as “one of the most thrilling days of my dancing career.”

WEEK EIGHT: August 29-30

Week eight was a solo program performed by Barton Mumaw with works created by Shawn and Mumaw.

WEEK NINE: September 5-6

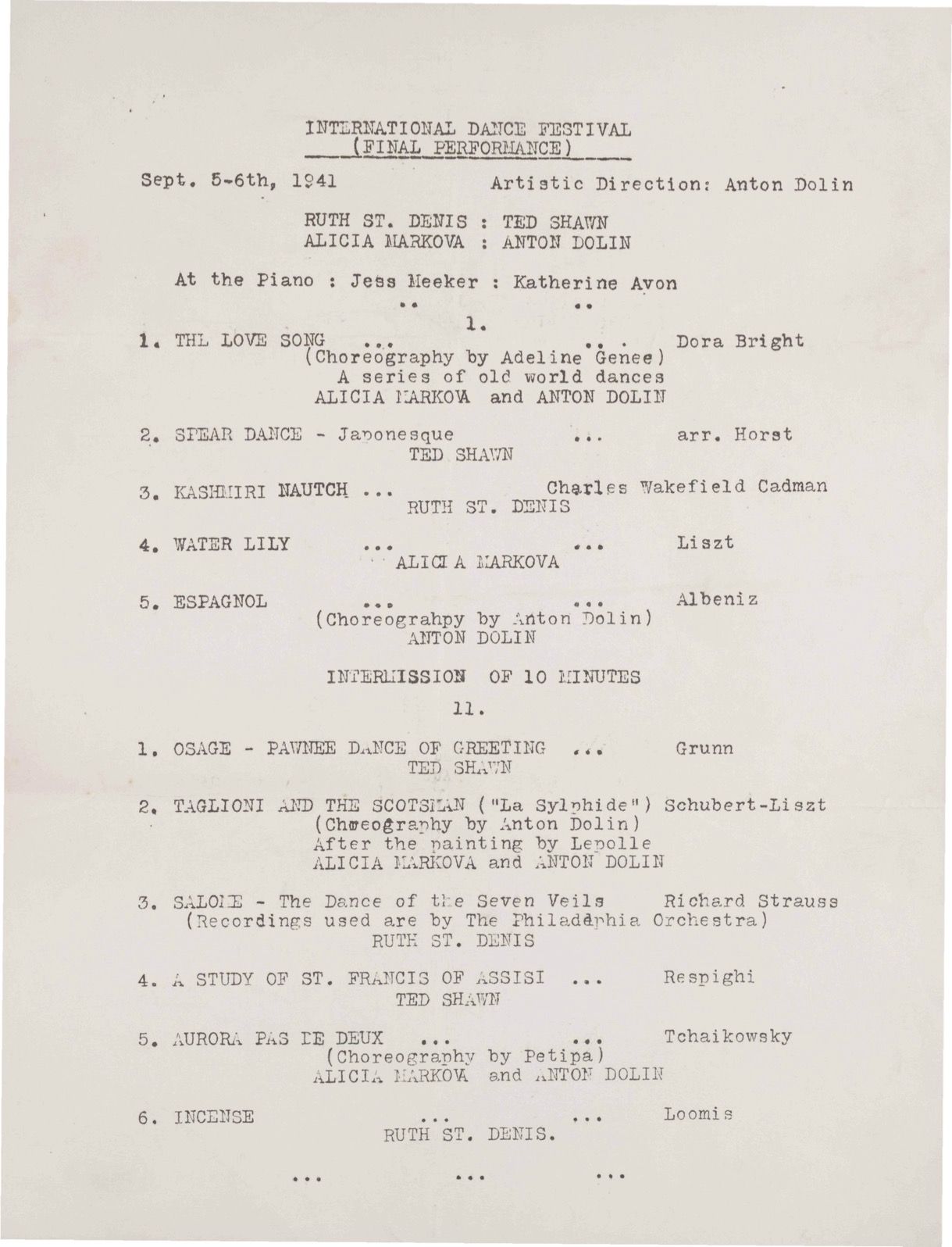

The ninth weekend and final performance of the festival was a shared bill with Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, Alicia Markova, and Anton Dolin. Markova and Dolin performed The Love Song, La Sylphide, and a pas de deux from The Sleeping Beauty together, as well as one solo each: Water Lily by Markova and Espagnol by Dolin. St. Denis performed Nautch, Salome, and Incense, and Shawn presented his Spear Dance, Osage-Pawnee Dance of Greeting, and A Study of St. Francis of Assisi.

What Happened Next?

By late August/early September the Ballet Theatre dancers had returned to New York to prepare for their upcoming season and the students had left. The fate of “The Farm” once more hung in the balance. Despite the summer’s success and requests and encouragement from patrons, Shawn could not afford to keep Jacob’s Pillow on his own.

In October 1941 a meeting was held during which a group of Berkshire people together with Markova and Dolin’s benefactor, Reginald Wright, approached Shawn with an idea. Their plan was that:

A new, non-profit-making, artistic and educational corporation be formed by them which would buy the property from me, and build a proper dance festival theatre so that dance artists could have ideal conditions in which to show their work, and audiences have ideal conditions in which to see it. They asked me whether, if this was done, and the corporation engaged me as managing director, would I consent to stay on and conduct school and festivals at Jacob’s Pillow… I consented.

The Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival Committee was formed, and they began a campaign to raise $50,000 – $25,000 to be paid to Shawn for “The Farm” and $25,000 to build a theatre.Owen, A Certain Place, 12. Construction of what would become the Ted Shawn Theatre began in the winter of 1941 despite the proclamation of war on the 8th of December. As Owen writes, “the foundation was literally and figuratively laid for the festival we know today.”Owen, A Certain Place, 12.