Menard has (perhaps unwittingly) enriched the slow and rudimentary art of reading by means of a new technique—the technique of deliberate anachronism and fallacious attribution… Attributing the Imitation Christi to Louis Ferdinand Céline or James Joyce—is that not sufficient renovation of these faint spiritual admonitions?"

The Long Arc of Dance History

Louis Horst, longtime collaborator of Ted Shawn and author of the classic book on dance composition, Preclassic Dance Forms, wrote that “Its contemporaneousness with the tempo of our time is the gauge by which we measure the dance.” For Horst, a vital metric of any performance’s success was the extent to which it resonated with the energies of its lived moment. The more “contemporary” a dance, the more thoroughly of its time it appeared, and the more engaging it might be for its audience. In the context of the long arc of dance history, however, Horst’s tenet brings us to something of a paradox: the more timely a piece of art, the more obviously dated it becomes. With dances, as with vocal cadences and haircuts, contemporaneousness comes at the cost of having to explain oneself to future generations.

Artists cannot anticipate future contexts in which their work will be viewed, and so art produces differing, uncontrollable meanings depending on the where, when and how it is experienced. To understand historical dances requires simultaneous attention to a work’s resonance in our time, as well as those previous. Many dance historians seek to understand the original experience of a performance by reading through reviews, journals, notes from performers and audiences so as to potentially glean a work’s originating intentions and affects, rather than be bound exclusively to meanings found in one’s present. Experiencing a work out of one’s own time is impossible, of course, but the attempt to do so is a frequently generative practice in the exercise of critical empathy.

The comparison of dances from one historical epoch to another can be jarring. My dance history students, for example, accustomed to decades of normalization of the frequently emancipated, quicksilver bodies of the “Balanchine ballerina,” often find it difficult to watch archival video of the great Margot Fonteyn. One might contemporarily compare her to the ballerinas of our moment (Peck, Whelan et al.) and think Fonteyn too slow, too thick, and too smiley, and when she kicks up her leg it barely goes above her waist!

Contemporary aesthetic expectations have cultural gravity, and historical work requires contextualizing conversation about the arc of standards of beauty and technical excellence as they mutate over time. In Western dance, to talk about aesthetics is to talk about bodies—what bodies are au courant, deemed attractive, acceptable, and ideally expressive. Discussions about dance aesthetics are necessarily about physical markers of difference: race, gender, ability, and sexuality, among others.

Introducing Adam Weinert

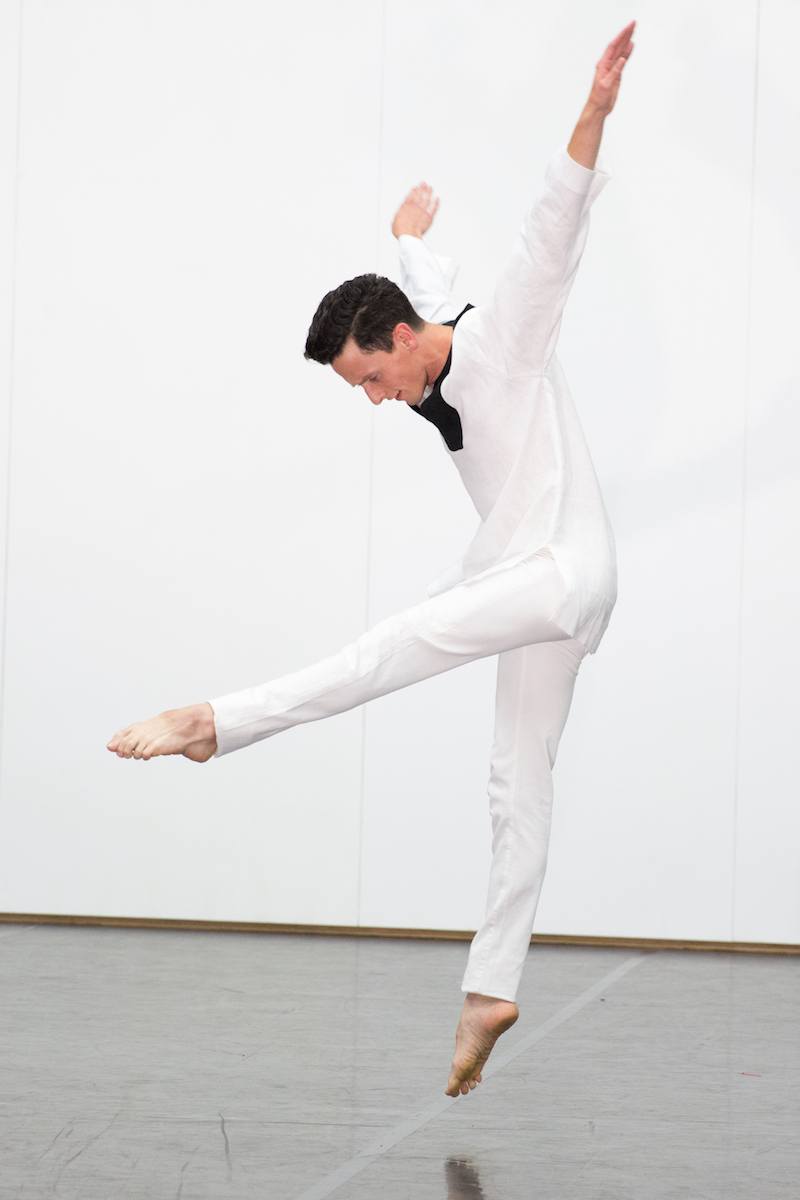

To make dances is to be in dialogue with other bodies throughout history, and no other living artist manages this discourse with the attention and acuity of Adam Weinert. Juilliard-trained and NYU-pedigreed, Weinert is a dancer and choreographer most acclaimed for his re-imaginings of the repertory of an earlier dancer and choreographer, the founder of Jacob’s Pillow, Ted Shawn. The form and format of Weinert’s work varies, and he is as fluent in proscenium performance as in emerging digital media and apparatuses of capture. A common leitmotif of Weinert’s work (arguably since he was a dance student at the Pillow in 2003) is meticulous attention to the works of the early modern dance canon, and carefully crafted interventions in their re-presentation.

Weinert is a choreographer who, in true Borgesian fashion, presents meticulous duplicates of historical repertory, lovingly forged copies of dance historical movements. Weinert draws on archival sources to exquisitely, exactingly recreate nearly century-old dances, and in presenting them contemporarily, provide new context and novel meaning-making opportunities for seldom-performed works. Weinert trucks in authentic forgeries, old dances made new, and grants new interpretive possibilities to work that might otherwise be written off as anachronistic, specious, or irrelevant. While this intentionally duplicative choreographic project has resonance with a Warholian animus, I think the alchemy of the work is more driven by deep respect for dance history and plain, unabashed love for the form—a trait that he uncoincidentally has in common with his frequent subject, Ted Shawn.

Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen

Consider “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” from Shawn’s longer work, Four Dances Based on American Folk Music. Shawn premiered the dance some five blocks from my Brown University office at the Providence Opera House in the early months of 1931, a few weeks before the building was closed and demolished. The song that lent the dance its title, “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” is an African American spiritual first printed in the mid-19th century that found mass-market popularity in the 20th. (Marian Anderson recorded a version in 1924, a lush recording of which is available online via the Library of Congress, and Louis Armstrong recorded a version in 1931, the same year Shawn’s dance premiered in Rhode Island.) Shawn choreographed the piece to a widely circulated song rooted in the experience of slavery, and intended his “Nobody Knows” to render the African American experience, to the extent possible anyway, for a privileged white man.

In this recording filmed at Jacob’s Pillow in 1938, we see Shawn clasping his hands, seemingly bound, with constrained, collapsed energy, and repeated gestures where Shawn holds head between his hands, reaches upwards with upturned palms, and returns to the ground with a sense of frailty and weakness. The lyrics to the song—unsung in performances of Shawn’s dance but likely known to his audiences—invoke suffering, faith, and eventual heavenly rest. Shawn’s movements restate these unsung motifs, and reify their meaning through the medium of his fit, white body.

Shawn did not, to my knowledge, have any particular claim to understanding the plight of millions of displaced, kidnapped, or murdered African people and their families, nor to the experience of being African American. This didn’t stop Shawn, who was well practiced in such appropriative maneuvers, and alongside Ruth St. Denis, spent much of his career presenting cultures other than his own on stage. In this way, “Nobody Knows” resembles other famed Shawn-dances-as-an-other performances, including, but by far not limited to, such works as Mevlevi Dervish (a take on Sufism), Feather of the Dawn (the Hopis) and The Cosmic Dance of Siva (the Bhahgavad Gita and Hinduism). Shawn was far from alone in his free interpretation (or wholesale invention) of the danced stories of others—there are decades of modern dance history and dozens of choreographers whose careers were grounded in the practice of broad orientalism. Shawn’s “Nobody Knows” was part of a larger suite of dances titled, Four Dances Based on American Folk Music, and there is something to be said for his curatorial inclusion of the African American experience in a dance dedicated to American themes. Shawn is appropriating, but in the attempted service of a kind of inclusivity, however problematic that may seem today. The solo represents an ambivalent mix of racist performance practices, yet gestures towards a sort of social justice that is not easily rationalized or reconciled.

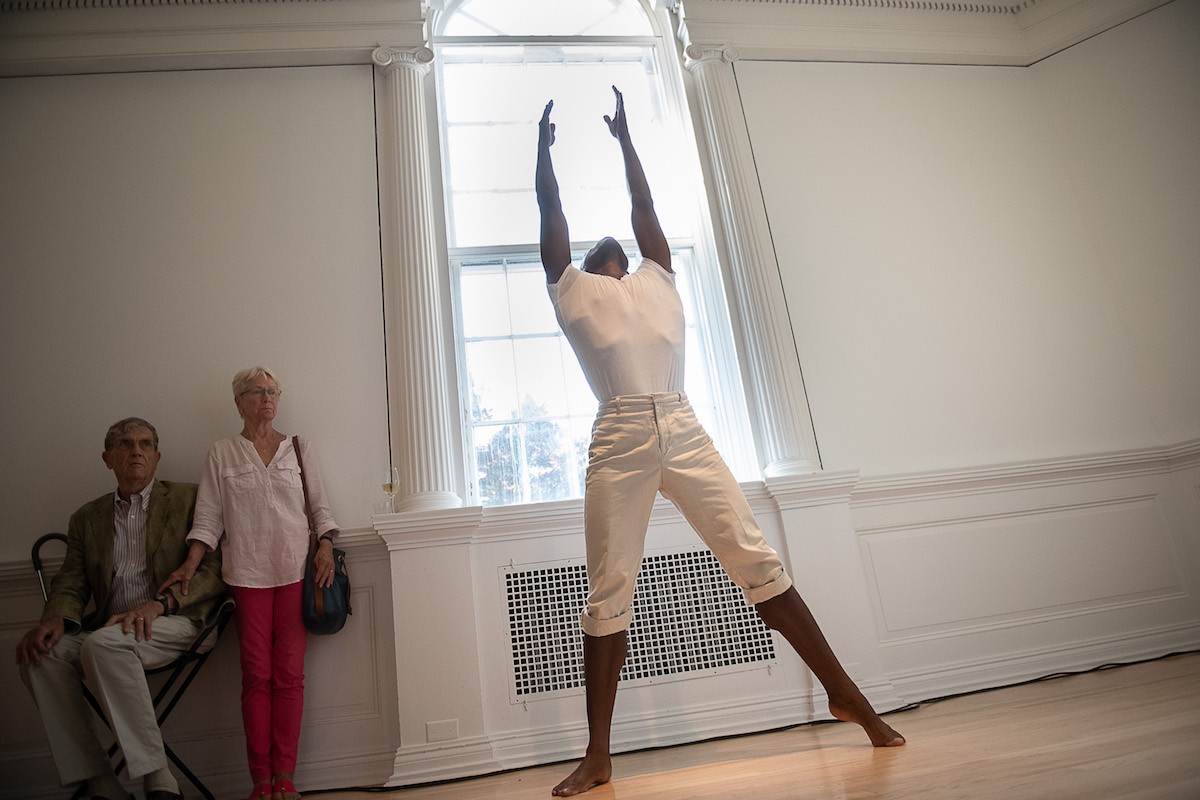

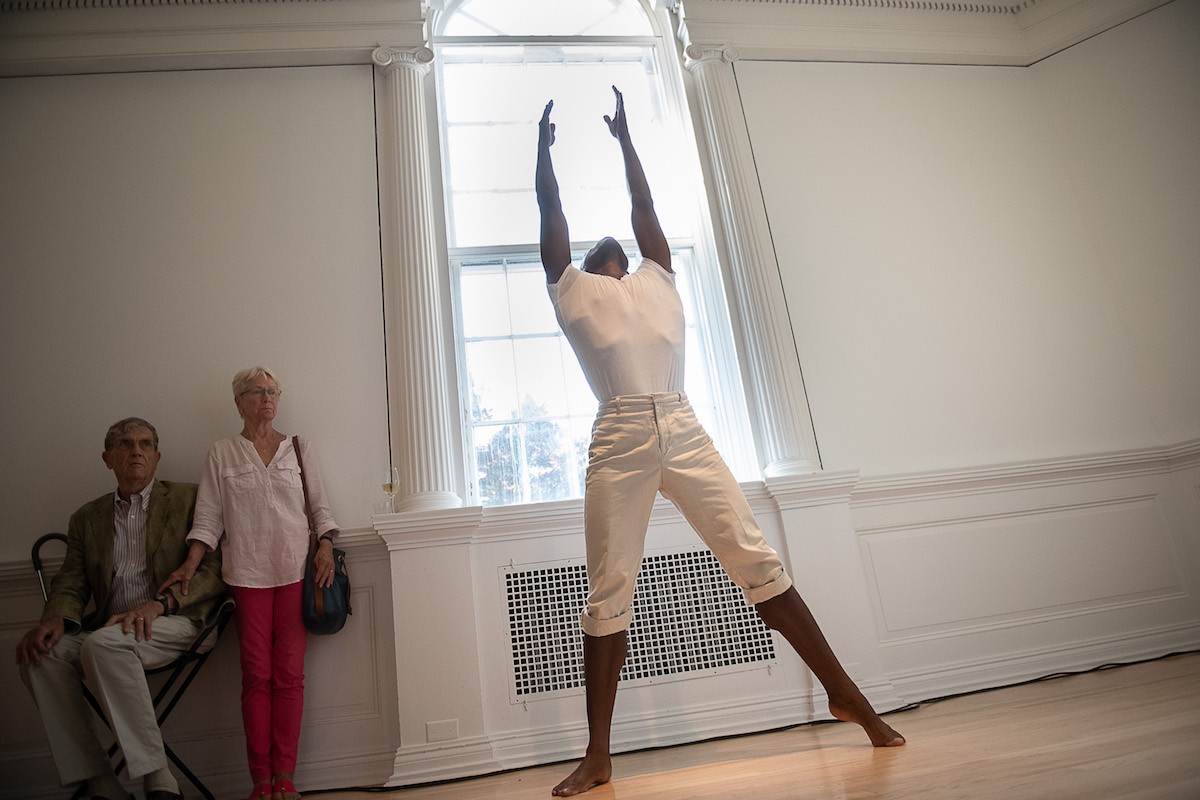

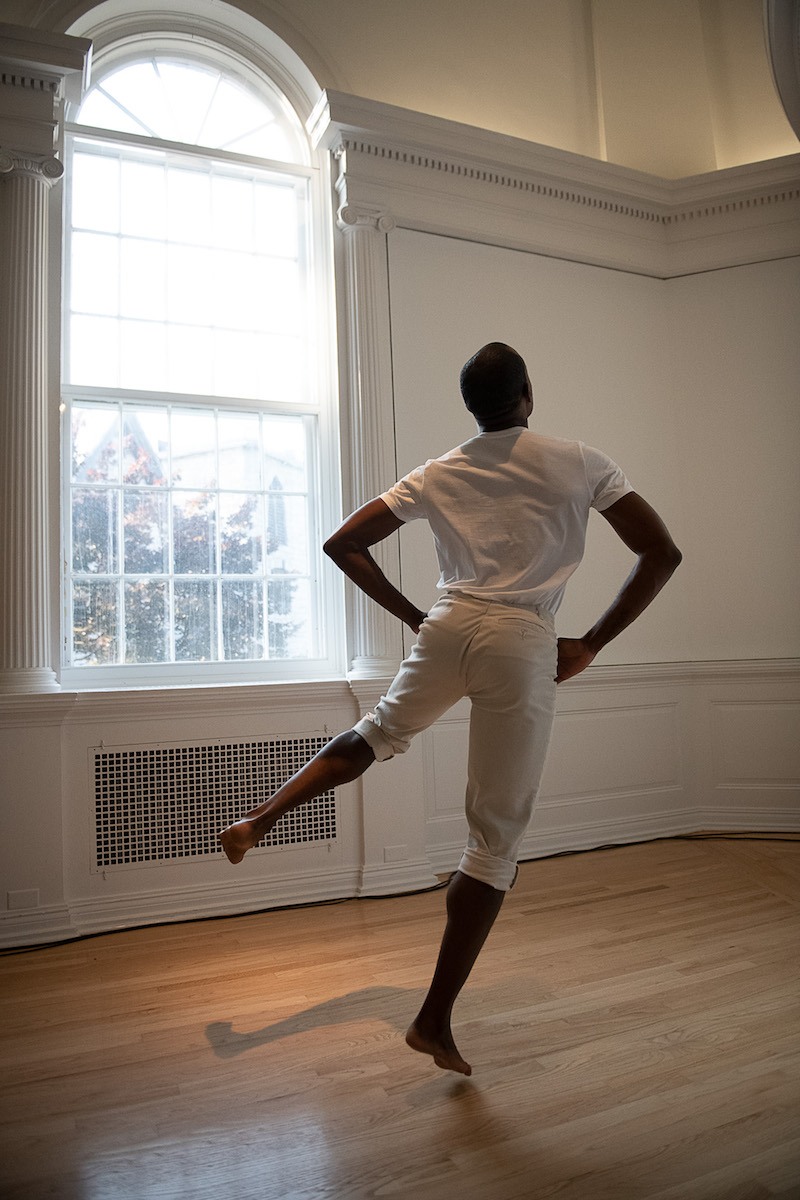

For recent performances of “Nobody Knows,” Weinert engaged the phenomenal queer black dancer and acclaimed drag performer, Davon Rainey. With this choice of casting, the original dance’s racial problematics are not resolved, but they are acknowledged and prismatically amplified. Rainey’s version of the solo—which Rainey collaboratively recreated with Weinert—is technically perfect, functionally identical to Shawn’s original, but with subtle, intentional differences in shading that markedly shift the potential meanings of the dance. The old and new dances are technically identical, but affectively distinct.

Shawn’s rendition is interspersed by frequent collapses of the head into the shoulders and his core to the floor, as though Shawn’s body were trying—and failing—to escape gravity, or ties that bind him to the ground. In Rainey’s performance, while the body still descends, it does so glidingly, in a controlled and seemingly intended descent. Rainey is—unlike Shawn—expert in mid-20th century modern techniques, and there are moments in Rainey’s performance inflected by the bodily postures and movement theories of Limón, Taylor and Sokolow, choreographers who—again, unlike Shawn—had deep relationships with The Juilliard School where Rainey and Weinert studied. Perhaps some of the different physical affects Rainey brings to the solo are the result of training and conditioning, to say nothing of the obvious striation of race. Rainey is also just more flexible, able to maintain the frontal orientation of the pelvis relative to the feet while bringing the head fully to the floor. Shawn looks more crumpled, perhaps, because he is less pliable in his hips and unable to maintain distal space between body parts like Rainey can.

Such subtle kinesiological disparities make worlds of difference in performance, as fundamentally identical choreography produces a wealth of contradictory significances. With its shaggy falls and sudden drops of weight, Shawn’s performed character reads as battered, broken, and defeated, whereas Rainey’s buoyancy and lift renders authority, agency, and inner and physical strength. In a recent interview with me, Weinert said, “You can’t separate the interpreter from what’s being interpreted.” In this light, the differences between Shawn and Rainey are palpable, representative of their individual truths and the contemporaneousness of their own time. Weinert and Rainey don’t seek to resolve the problematics of Shawn’s solo, but providing choreographic room to ruminate is a credit to Weinert’s (and Rainey’s) abundant skill.

Moving Forward

Weinert is expert at re-introducing historical dances into unexpected contemporary contexts. Most recently, he has been exploring the nascent technology of Augmented Reality (AR), where digital images are animated on top of live video through software and an intermediating screen such as an iPhone. In “The Reaccession of Ted Shawn” he used this technology to bring “Nobody Knows” (among other works) to New York’s Museum of Modern Art as part of a larger augmented reality project, and recently received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to deploy AR and the Shawn repertory to engage young men on the autism spectrum in Otsego County, New York. In 2018, he released a film, MONUMENT, that places the Shawn repertory into new filmic context for a growing national audience. The work features Rainey performing a variation of the “Nobody Knows” solo costumed in a dress and descending a staircase, richly re-imagining the solo and its queer trappings, and concluding with Rainey, radiantly lit by sunlight walking majestically away from the site of his slow-motion fall. The film closes with Weinert’s company doing a widely spaced excerpt from Shawn’s Kinetic Molpai, highlighting Shawn’s attempt to foster a quintessentially American and essentially masculine dance by performing in a baseball diamond. They move swiftly and circuitously around the pitcher’s mound, but in keeping with the anxious tenor of our time, are filmed at stunning height by a surveillance drone.

PUBLISHED January 2019