Racial Proscriptions and African-American Dance Traditions

Beginning in the early 1940s, the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, under the directorship of pioneering dancer/choreographer Ted Shawn, assumed an invaluable role in the dance world by becoming a venue where artists—both well-established and emerging—could present their work, teach and choreograph for students, and generally revitalize themselves by spending time in a supportive environment. At a time when artists of color were still fighting to make inroads in areas that had stringent racial proscriptions, the Pillow extended a welcoming hand. During the decades surrounding these inclusive initiatives, black dancers and choreographers faced the same types of proscriptions as individuals in other fields of endeavor. Racial biases affected them in terms of the places where they were permitted to pursue professional training, the venues where they could perform, and the critical responses they received.

In this series of essays about black artists who performed at the Pillow, there are references to artists such as Janet Collins and Talley Beatty who attempted to find studios that would accept them as students during the early years of their training. The standard response to their inquiries was that the parents of white students would not tolerate integrated dance classes, and they would withdraw their children if a black student were enrolled. In other instances, we find that artists like Beatty, Katherine Dunham, and others were constantly searching for housing accommodations as they toured throughout the U.S., often turning to leaders in black communities to help them find lodging with local residents. Moreover—in an instance that had to do with the actual denial of an artist’s appearance on stage—Janet Collins was not allowed to tour with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet when the company traveled to the southern region of the United States. Examples such as these indicate that dance artists were engaged in struggles for equality that paralleled those that occurred in other areas of American life.

The conflation of race and class often determined which areas of the performing arts were accessible to black performers.Racial proscriptions in the arts also reflect a complex matrix of factors that has historically resulted in the exclusion of black people from certain aspects of the American experience. As discussed in other essays in this series, the conflation of race and class often determined which areas of the performing arts were accessible to black performers. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, for example, popular genres such as minstrel and vaudeville shows—“lower class” forms of entertainment—were acceptable for black performers to engage in. But, as the “high arts” continued to develop in America, during the 1920s and onward, African-Americans found it very difficult to be accepted as serious participants in arenas such as classical ballet and opera.

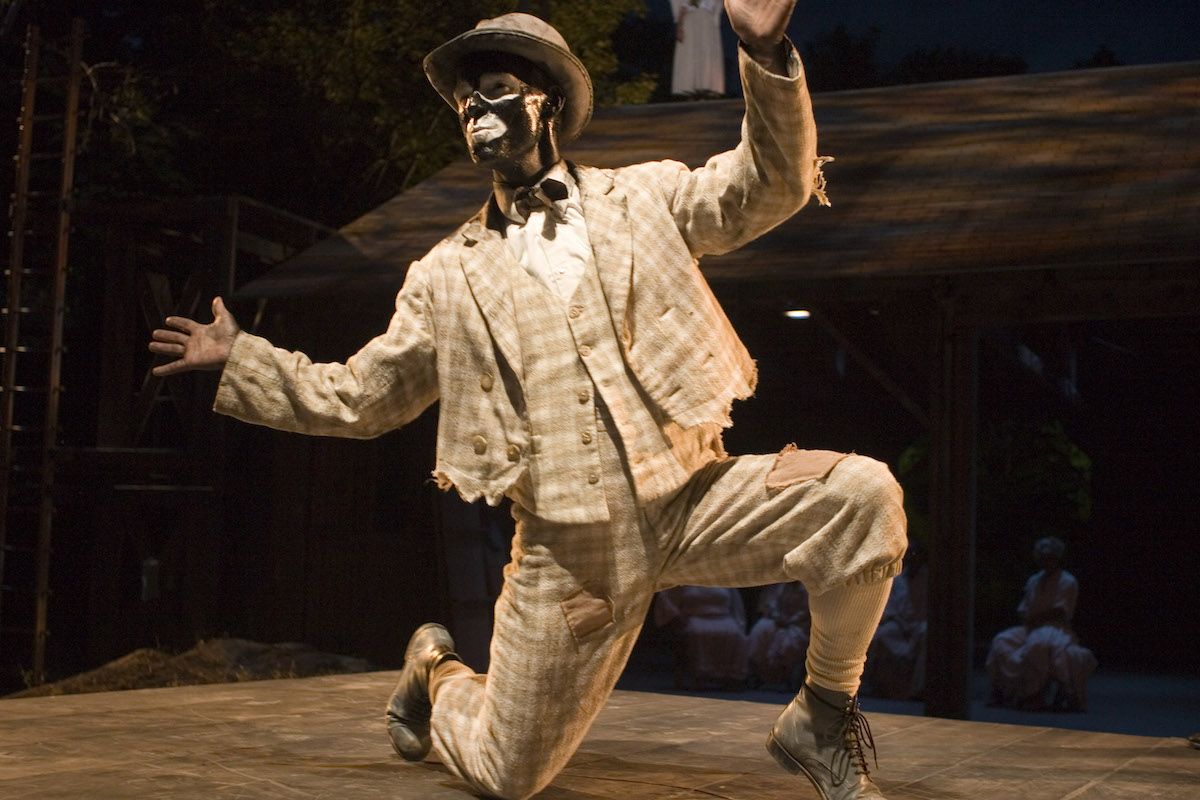

As an example of acceptable fields for blacks to engage in, minstrelsy is an especially interesting area. Its very essence was based on images of black people as comic, ignorant buffoons; and even though nineteenth- and twentieth-century minstrel companies were composed of both white performers (in blackface) and black performers (sometimes also in black face) the messages of racial inferiority were clear. As the most popular form of entertainment in America, the shows hammered home racist messages. One choreographer who created work for the Pillow—Joanna Haigood, who I will discuss in more detail later—used images of minstrelsy and popular-nineteenth century black performers in her 1998 work Invisible Wings.

In a related vein, cultural critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr. points to the period between 1890 and 1910 as a time when American households were filled with “heinous representations of black people, on children’s games, portable savings banks, trade cards, postcards, calendars, tea cosies, napkins, ashtrays, cooking and eating utensils—in short, just about anywhere and everywhere a middle- or working-class [white] person might peer in the course of a day.”Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, Thelma Golden, ed. (New York, NY: Whitney Museum of Art, 1991) p. 11-12. Here we can envision a continuum that stretches from racist ideology, to social and political practices, to material culture, to the performing arts; and we can, again, see the complexity of the situation.

During different periods, African-American artists dealt with oppressive environments in different ways. Elsewhere, I have written of how they negotiated racial proscriptions during the period that eventually became known as the Harlem Renaissance. Based on an idea called sociological positivism, the black intelligentsia of the period—roughly 1920 to 1930—believed that African Americans could improve their lot in American society by attaining recognition and success in artistic endeavors, because they belonged to a race that was innately gifted in those areas.John O. Perpener III, African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Chicago and Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001) pp. 15-16. Though the idea of “natural” racial dispositions is one that has long been debunked, it was embraced during the 1920s as a reasonable way for African Americans to pursue racial parity in American society.

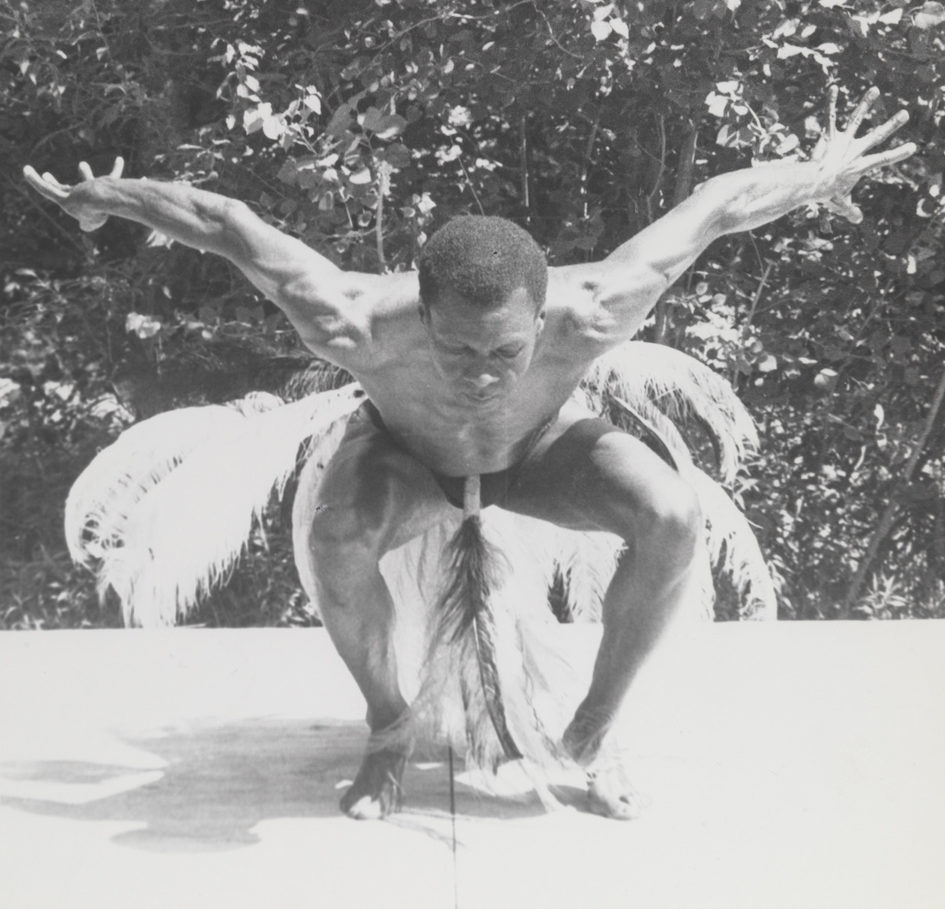

In one of this series’ essays I discuss Asadata Dafora—an African artist who moved to America in 1929—and his objective of presenting West African music, dance, and folklore in such a way that it would be appreciated as an important contribution to the world of art.

To achieve this, he presented his work in mainstream venues, before mostly white audiences, and within the purview of the New York critical establishment. Along the same lines, Katherine Dunham voiced her desire “to attain a status in the dance world that will give the Negro dance student the courage really to study, and a reason to do so. And take our dance out of the burlesque to make it a more dignified art.”Katherine Dunham, quoted in Frederick L. Orme, “Negro in the Dance as Katherine Dunham Sees Him,” American Dancer, March, 1938, p. 46. In spite of these early artists’ groundbreaking achievements and their own unerring confrontations of racial barriers, their expressions of racial uplift that centered on proving to others that black artists were worthy of acceptance eventually became anathema to the activists/artists of later generations.

By the 1960s, African-American artists were developing radically different approaches than those of their earlier counterparts. They were turning away from the accommodationist practices of their predecessors and seeking more militant solutions. Larry Neal, a poet, essayist, and primary ideologue of the Black Arts Movement, spoke of these new directions in the following:

. . . The Black Arts and Black Power concept both relate broadly to the Afro-American’s desire for self-determination and nationhood. Both concepts are nationalistic. One is concerned with the relationship between art and politics; the other with the art of politics.

Recently, the two movements have begun to merge: the political values inherent in the Black Power concept are now finding concrete expression in the aesthetics of Afro-American dramatists, poets, choreographers [my emphasis] musicians and novelists. A main tenet of Black Power is to define the world in their own terms. The black artist has made the same point in the context of aesthetics.Larry Neal, “The Black Arts Movement,” in The Black Aesthetic, Addison Gayle, Jr., ed. (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1972) p. 257

During the Black Arts Movement—roughly 1960 to 1975—artists made it a point to turn their backs on America’s arts establishments. They began to form their own organizations, open their own cultural centers, and cultivate their own critics. In their efforts to assure that their art confronted racial oppression by embracing messages of self-definition, self-knowledge, and self-esteem, they literally took their art to the streets of inner-city communities. Initiatives such as the Jazzmobile and the Dancemobile in New York City transported artists to perform on street corners, and in empty lots and playgrounds. Local residents saw serious, non-commercial art that they would not have been able to see otherwise.

In this series of essays, in contrast to Asadata Dafora, Talley Beatty, and Janet Collins, a later generation of artists who appeared at the Pillow is represented by artists like Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, the founding director of the Urban Bush Women.

Zollar began her career during the 1970s, when the influences of the Black Arts Movement were being felt throughout the country. Giving all due respect to the work of artists who laid an aesthetic foundation for her to build on, she has brought social and political commentary to the foreground to an extent that earlier black artists never dared.

Though many things have changed since the 1930s and 1940s—both in artistic arenas and in the dynamics of race relations in America—there have been underlying sociopolitical problems that continue to affect black Americans. Younger artists have pointedly used their work to frame contemporary issues. Moreover, Zollar has widened this artistic purview by choosing subject matter that includes homelessness, violence against women, and environmental issues in works such as Shelter (1987) and Bitter Tongue (1987).

Because black artists have consistently performed at the Pillow for such a long period of time, it is possible to examine both the changes and the continuities that have occurred in their artistic practices. One can see, for example, how distinctive movement vocabularies have been passed from one generation to the next. An artist like Charles Moore, who visited the festival with his company in 1976 and 1978, used movement techniques and styles he had learned from the earliest black participant at the Pillow, Asadata Dafora.

As a child, Jawole Zollar studied with Joseph Stevenson, a former Dunham dancer, and she went on to create works that drew on her ever-expanding knowledge of African-diaspora dance. Her work has also been compared to that of Pearl Primus, with whom she never studied. And I would add that dance movement languages are not only passed from teacher to student, but they are also passed through acculturation processes, as individuals are exposed to vernacular dance in black communities, or to the gestural movements, kinetic patterns, and postures that become habituated through one’s daily comings and goings in a given environment.

Dance historian Jacqui Malone alludes to the underlying dynamics of the continuity between the dances of Africa and the dances of diaspora communities, when she states, “Recognition of the strong relationship between the dances of traditional African cultures and the dances of black Americans is now a commonplace among students and scholars of American history, music, and dance.”Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance (Chicago and Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996), p. 24. She continues this idea by describing how “certain movement patterns, gestures, attitudes, and stylizations present in the body language of black Americans are assertive proof of African influences.”Ibid. And, finally, she cites music historian Albert Murray who said that African Americans “refine all movement in the direction of dance-beat elegance. Their work movements become dance movements and so do their play movements; and so, indeed, do all the movements they use every day, including the way they walk, turn, stand, wave, shake hands, reach, or make any gesture at all.”Ibid.

But, if we look again at the performances of black artists at Jacob’s Pillow over the years, we can also see aesthetic variations. As mentioned earlier, there is the evolving choice of subject matter that artists use in their works; and, there is also the ongoing exploration of new movement sources. These include the postmodern dance techniques that evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, the movement innovations of urban hip-hop during later decades, and borrowings from other movement traditions such as Japanese Butoh. The stories of the artists discussed in these essays, and their visits to America’s oldest dance festival, provide important insight into their attempts to secure a foothold in the larger arenas of American art and culture.

A Brief Look at Black Life in the Berkshires

African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley is a book that documents the African-American presence in the geographic area where Ted Shawn founded the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. It records the stories of some of the individuals who represented the earliest presence of black people in the area; it also tells the stories of African Americans who fought for their peoples’ freedom during a period that stretched from the anti-slavery activism of the eighteenth century to the civil rights initiatives of the twentieth century; and it recounts the stories of individuals who, during those same periods, made significant contributions as entrepreneurs, educators, religious leaders, and in a wide range of other fields.

The book highlights the lives of individuals such as William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, who was born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts (roughly 20 miles from the Pillow). In addition to being the preeminent civil rights leader of his time, he also served as a leader of the black intelligentsia that founded the artistic and cultural movement that became known as the Harlem Renaissance. As contributor Barbara Bartle describes it in African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley, “[T]he movement’s demise came quickly with the Great Depression. But while it lasted, it was an optimistic time, when many Harlemites thought that the race problem could be solved through art—‘civil rights through copyright’ was a popular slogan.”Barbara Bartle, “The Harlem Renaissance,” in African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley, David Levinson, ed. (Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing Group, 2006), p. 129.

Several other key individuals of the Harlem Renaissance were associated with Berkshire communities. Renowned African-American photographer James Van Der Zee was born in Lenox in 1886. Barbara Bartle also comments on his significance, “At his death it was said that he was a man who saw beauty in people and was willing to work hard to get his camera to see it. He recorded a time, place, and culture—Harlem during its renaissance—that we can recapture as vividly as any decade in our history.”Ibid., p. 132.

In the book’s chapter, “Entertainment and Social Life,” we learn that the ubiquitous minstrel show was part of popular entertainment in the upper Housatonic valley, just as it was in the rest of America, and racist performances of Uncle Tom’s Cabin also took place in area theaters.Ibid., p. 123. On the other hand, in 1926, one could see a production of the groundbreaking, all-black musical Shuffle Along, at the Colonial Theater in Pittsfield.Ibid.Shuffle Along had opened to positive reviews on Broadway in 1921 with a stellar cast that included Florence Mills, Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, and Adelaide Hall.

“Jacob’s Pillow,” an entry written by Norton Owen, Director of Preservation at the festival, provides an overview of some of the activities that African-American dancers and choreographers engaged in over seven decades. Owen quotes the Pillow’s founder, Ted Shawn, as a testament to the artist’s abiding interest in world dance:

The dance includes every way that men of all races in every period of the world’s history have moved rhythmically to express themselves.”

Shawn underscored his interest in this direction by presenting concerts that were remarkable for the diversity of their artists, including black artists from Africa, America, and the Caribbean. At the end of his essay, Owen also mentions a remarkable piece of dance theater that was not only an exceptional example of the contributions of black artists to the festival, but it also incorporated an aspect of local history that was rooted in the very ground that Jacob’s Pillow was built on.

The farmstead that Ted Shawn purchased in the 1930s as a summer home for his all-male dance company belonged to the Carter family. It has long been thought that members of that family were involved in the nineteenth-century anti-slavery movement known as the Underground Railroad, a series of routes dotted with safe-houses and other locations where escaping slaves could rest and be nourished as they traveled north toward freedom in Canada. Information about the actual locations of the stopovers is sketchy because of the secrecy surrounding every aspect of these journeys. As Barbara Bartle explains, “Often it has been difficult to document these sites because they may have been hidden rooms or chambers that have been altered, the houses may have been demolished, or sites may have consisted only of barns, caves, and secret passageways.”Ibid., p. 29.

However, she goes on to explain that researchers have recently located secondary sources indicating specific individuals in Berkshire County who were involved in the Underground Railroad, and among these she lists Stephen Carter who served as a stationmaster during the mid-nineteenth century.Ibid.

Invisible Wings: A Pillow Metaphor

In 1993, while working on another project at the Pillow, San Francisco dancer/choreographer Joanna Haigood began investigating the story of the locale’s place in the annals of African-American history. While in residence that summer, she had an experience that made her realize that the place somehow felt like a “safe haven,” and that inspired her to begin looking into the property’s history. The most striking fact she found that supported her intuitive feelings was that the Carter farm had served as a station on the Underground Railroad. That began the journey that led her to individuals like Charles Carter, the great-great-grandson of Stephen Carter.

After years of meticulous research, Haigood premiered Invisible Wings on August 25, 1998. Her extensive background in site-specific dance productions led her to use the grounds of Jacob’s Pillow as the stage on which the narrative of nineteenth-century journeys toward freedom unfolded. Her performance required that the audience travel with the performers to different sites that comprised the Carters’ old homestead, intensifying the verisimilitude of the different vignettes. She explained her use of the grounds in a talk preceding the work’s premiere:

There’s a lot of walking in this piece . . . . What I’m trying to do is bring the audience . . . to pull the audience back in time into the nineteenth century, around 1850, which was probably the active time of this station. And, to do that, it was important for me to find a way to disorient people who are obviously very familiar with this property. So . . . There is a disorientation section. . . . And, kind of a set up to give you a more sensate experience of what it might be like to be escaping; to go through the various levels of fear, of joy, of making it . . . by setting up an environment that supports some of the concepts . . . . that you have your own experience by walking through these environments.Norton Owen, Interview with Joanna Haigood, Identifier 1189, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, August 30, 1998.

The storyteller, performed by Diane Ferlatte, opened Invisible Wings with a powerful monologue that set the scene as the audience surrounded her. She recounted events that exist somewhere between truth and legend. That is, the stories have been passed down from generation to generation, by word of mouth, without the certainty of written documentation. There is a kernel of truth in them, but they have also been elaborated on, giving them a mythic patina. The first one she tells is of a slave who has escaped from his plantation, but his head is encased in a metal cage that is supported by a collar around his neck. Several bells are attached to the top of this diabolical contraption, so that his movement is always accompanied by their constant clanging. Because of the limitations of his movement and the noise that he makes, he can be more easily tracked by slave catchers.

Having set the horrific scene, the storyteller goes on to recount how a stranger finds the slave in the woods and tells him to stay where he is until he returns with a tool to free him from his entrapment. But, when the stranger returns the next day, he finds that the slave has hung himself from a tree in a fit of despair, and black birds swarm around his dangling corpse. In a final macabre irony, the birds are never able to feast on the corpse, because every time they disturb it, the clanging bells scare them away. The storyteller’s words cut through the darkening evening at Jacob’s Pillow like a stab to the heart of this darkly malevolent history.

Ferlatte continues with another unsettling story that reveals how the Underground Railroad came to have its name.

As the performance unfolds, the audience continues to move from place to place. They actually see the slave running through the woods with his head caged and witness depictions of other events that might have occurred as escapees moved northward toward freedom. One striking scene depicts how a slave-master, with the help of his black assistant wrenches a young girl from the desperate grip of her mother, so that the child can be sold to someone else. The vignette takes place high above the audience on a narrow platform that stretches the length of an old building’s roof. Haigood’s brilliant staging intensifies the effect of her work’s magical realism, the juxtaposition of all-too-real occurrences with implausible surroundings. (I think of paintings by Marc Chagall with peasants and cows flying above rooftops.) Such images create a fascinatingly ironic mix of painful truth and perplexing illusion.

In another scene, a slave is suspended upside down, like one of those barbaric crucifixions, and whipped by his mistress who is the personification of maddened power. But, there is also a kind of impressionistic minuet—between master, mistress, and slaves—in which the players trace their vexed relationships in the floor patterns and gestures they make. One is reminded of how another artist, José Limón, used this convention of figured dancing in The Moor’s Pavane (first performed at the Pillow in 1951) that delineated the relationship between Othello, Iago, Desdemona, and Emelia.

Other elements of Invisible Wings are used in such a way that they bring some welcome levity to the work. Of course, music and dance are chief among these elements. Haigood explained how she depended heavily on her music director, Linda Tillery, to gather the songs, percussive rhythms, and chants that accurately reflected African-American slave culture of the period. Their research included spending time among the Gullah people, descendants of slaves who have lived in isolation of the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia. Echoes of antebellum slave culture could still be heard in the music and speech patterns of these people. That region was also where Haigood’s family roots were, so she had personal ties to individuals who revealed fragments of cultural history. Her uncle, for example, demonstrated the “snake hips,” an undulating dance that can be thought of as part of the living history of African-American dances that are passed from one generation to the next, paralleling the oral tradition of storytelling. In the same vein, she studied the embodied knowledge of the buzzard lope, shuffling, patting and dancing juba, and the ring shout. These were elements of music and dance that often served as a kind of salve to soothe the painful wounds of slavery.

Part of the stunning humanity of Invisible Wings is its deft delineation of the darkest moments that human beings can encounter in juxtaposition with the joyous expression of enduring and surviving—perhaps even thriving. And, Haigood concludes her work with another note of magical realism by referencing a mythical story that provides the piece’s title. One of the stories passed down from antebellum slave culture was that there were individuals who had magical powers that enabled them to escape to freedom by flying away, back to Africa. Using her skills as an artist accomplished in aerial work—the use of equipment that enables performers to be suspended high in the air—she ended Invisible Wings with an incredible moment where her character, Mary, one of the escaped slaves, is suspended from a crane, high above the buildings and the woods where the preceding scenes have unfolded. This moment of breathtaking transcendence provided a powerful conclusion with a message of consummate hope.

For me—at the expense of forcing a point—Invisible Wings can be thought of as a metaphor for the participation of black artists at Jacob’s Pillow, because many of those artists’ journeys involved finding safe spaces where they could study, perform, teach, and thrive. This was especially true for those who came to the Pillow in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. As mentioned before, Beatty and Collins searched for places that would accept them as students. Dunham and others looked for places to house and feed their companies when they were touring the U.S. Well into the 1960s, even Ted Shawn ran into problems finding housing in the surrounding communities for some of his artists. Though these were not life and death situations or ones that might lead to bodily injuries, as was the case with travelers on the Underground Railroad, they were unsettling situations fraught with their own emotional and psychological trauma.

These dancers’ art was their palliative, and finding a place that supported the creation and presentation of their art provided additional solace. Joanna Haigood spoke of her initial feeling that the Pillow was a place of refuge; and she described how she set out to create a piece of dance theater that would, in a sense, help the land of the old Carter farm reveal its stories about the people who had tread it. Over the years, since the festival’s formal incorporation in 1942, black artists have also come to the Berkshires, walking—indeed, dancing—on the same land and adding their own stories.

PUBLISHED December 2017