“She’s never heard of Denishawn,” Myra said. She remained seated, smiling up at her daughter,

expectant. Cora felt the first rising of strong dislike.

“You’ve never heard of Denishawn?” Louise, too, seemed confused.

“No,” Cora said. She hoped that if she were clear on this they would perhaps stop asking.

Introduction

I was an undergraduate choreography student when I first learned about Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, and the dance company they shared in the early 20th century called Denishawn. I remember being struck by the vowelly ease of the name, a portmanteau smashup of Shawn and St. Denis. I confess I felt a narcissistic kinship, and considered them dance historical precedents to the feminist intervention of my own last name—Skybetter—which combined my parents’ last names, bucked the patronymic trend (and Florida state law) and demonstrated the equal partnership between them. In 1915, fully five years before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote in the United States, St. Denis and Shawn were joined as lovers and business partners, on seemingly equal terms, with gender politics embedded quite literally in the name of the entity they created together.

The truth to Denishawn and its various afterlives is, of course, more complicated. The name of the company was coined in a competition run by a theater manager in Portland, Oregon, and wasn’t catalyzed by any particular political consciousness. There were feminist trappings to aspects of Shawn and St. Denis’s partnership—St. Denis refused to wear a wedding band and omitted the word “obey” from her marital vows—but the apparent symmetry and gender neutrality of the name Denishawn is in pointed contrast to Shawn’s lifelong fight for the visibility and credibility of men—specifically and especially men—in American dance.

The privileging of men in dance is so common as to be basically ubiquitous today, but this was not always the case. The American dance tradition originated from the minds, bodies, and labor of brilliant women, and was popularized and institutionalized largely by their efforts. Men played a role in these processes, of course, but it is not a coincidence that as the dance field gained institutional credibility and financial solvency, positions of power increasingly came to be occupied by men.

The subject of men and dance is thus an invitation to, yes, think about male-identified actors through dance history, but also an opportunity to contemplate how sex, gender, and power are enacted in the dance field. It is my hope that, far from being an idle historical exercise, this work will enable more fruitful ponderings of the gendered inequities of our contemporary moment. The study of history (or the act of writing, for that matter) is never a neutral task, and as such I am cognizant of a certain piling on of privilege here. As a man in dance writing about men and dance while curating essays by two other men in dance, there is a risk of a certain recursive, self-aggrandizing navel-gazing. Thus I—and my fellow writers—hope to consider how certain artists associated with Jacob’s Pillow work on notions of gender, as well as complicate them, render them ironic or reject them outright. We thus consider the subject of men and dance with a wink, as so many of the men lionized and canonized in our field have an, at best, un-straightforward relationship to masculinity and its presentation on stage.

The Career of Ted Shawn

The career of Ted Shawn reveals much about the historical progression of men and dance, and as he also founded Jacob’s Pillow, it seems appropriate to begin this series with him. Shawn was born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1891, and studied to become a Methodist minister at the University of Colorado. A bout of diphtheria brought on temporary paralysis, which caused him to redirect his energies to dance therapy, and he pursued dance professionally thereafter. In 1914, he met choreographer Ruth St. Denis, who he promptly married, and the two shared a touring dance group (Denishawn) until 1930, at which point the couple separated and the company disbanded. From 1933 until 1940 Shawn lead a new venture, Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers, which performed Shawn’s repertory and sought to dispel the notion that men who danced were “sissies” or effeminate. In the last decades of his life, Shawn took on the role of impresario, and produced the works of many artists including Carmen de Lavallade, Lester Horton, Merce Cunningham, and Pearl Lang at Jacob’s Pillow, the enclave for dance that he built, literally, with his (and his company’s) bare hands. He passed away in Florida in 1972.

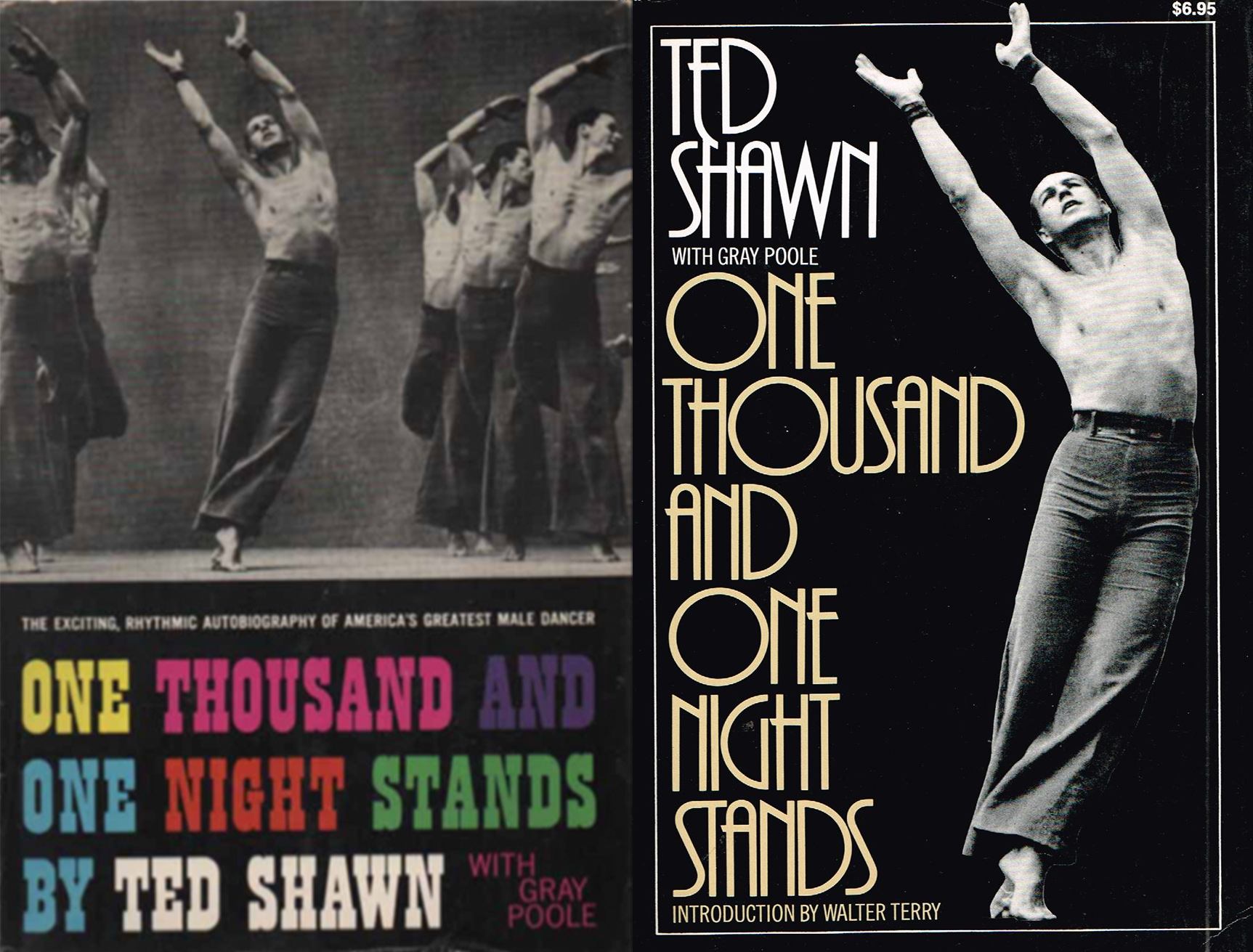

Shawn is described by his biographer, Walter Terry, as an “American Prometheus,” a titanic and near-divine figure who brought the sacred modern dance to humanity. Shawn indeed toured dances and dancers exhaustively around the world, and brought his choreography to myriad locales that had never been exposed to such material. Shawn’s autobiography, somewhat tellingly titled One Thousand and One Night Stands , is full of anecdotes of touring leading to teaching and teaching leading to students becoming professional dance artists, thus begetting still more touring, teaching, and proselytizing for dance around the country.

Shawn was instrumental in bringing modern dance to broader audiences in America, by his own labor as well as through the generations of artists he trained to do the same, a cohort notably including acclaimed choreographers Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey.

In keeping with the ambivalent myth of Prometheus (who brought fire to humanity only to be punished by being chained to a rock and subjected to an eagle who ate his liver for all eternity) the spreading of dance across the country was not without unanticipated consequences and complications. Shawn was absolutely a passionate advocate for the art of dance, but his own choreographic practice dabbled in orientalist fantasy, gendered stereotype, and nationalist posturing. He was one of the few early 20th century dance presenters to support artists of color through Jacob’s Pillow, but his own company only ever had white dancers. The reasons for this are complex, as it is not always possible to distinguish between an individual and their implication in structural inequality.The “America” in “Father of American Dance” has never been equally accessible to all who sought it. Many of Shawn’s dancers were drawn from colleges who didn’t admit people of color, and southern theaters to engage companies that broke the color line. The utopian, promethean spirit and historical aura of Shawn, the “Father of American Dance,” is tethered to the segregated reality of his time, a reminder that art with pretensions of universality only ever succeed inasmuch as “universal” is delineated with deliberate narrowness and specificity. The “America” in “Father of American Dance” has never been equally accessible to all who sought it. The same, of course, is true for training in the arts.

The Issue of the Male Dancer

Shawn dedicated much of his life to addressing (and, in his view, correcting) the image of the male dancer in the American zeitgeist. He attempted to provide counterexamples to stereotypes of the effeminacy of men who danced, while simultaneously espousing stereotypes of the relative weakness of women as a category. This critical move was urgent for Shawn in the early 20th century, as there didn’t seem to be much of a role for men in dance at that time.Shawn’s work is thus thoroughly enmeshed in questions of gender, and preoccupied specifically with the embodied presentation of masculinity on stage. Shawn’s work is thus thoroughly enmeshed in questions of gender, and preoccupied specifically with the embodied presentation of masculinity on stage. In his lectures at the Peabody Institute in 1938 (later turned into a volume titled Dance We Must) Shawn elaborated on the ostensive differences between male and female movement: “[W]omen’s movements are conditioned by cooking, sewing, tending babies, sweeping, etc., small scale movements which use comparable little stress through the trunk of the body and a greater use of the small arm movements, with resultant greater flexibility of wrist and elbow.” Men, meanwhile, deploy “movement impulses from forefathers who wielded scythe, axe, plough, oars, etc., and the masculine movement stress from the ground up through the entire body, culminating in big arm movements from the shoulder out, and with much less flexibility of elbow and wrist joints.”This selection is quoted from Julia Foulkes’ excellent text, Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism from Martha Graham to Alvin Ailey. Shawn, in attempting to escape the confines of the popular stereotype of sissy dancers reinforces stereotypical differences between men and women to put his dancemaking in masculine context.

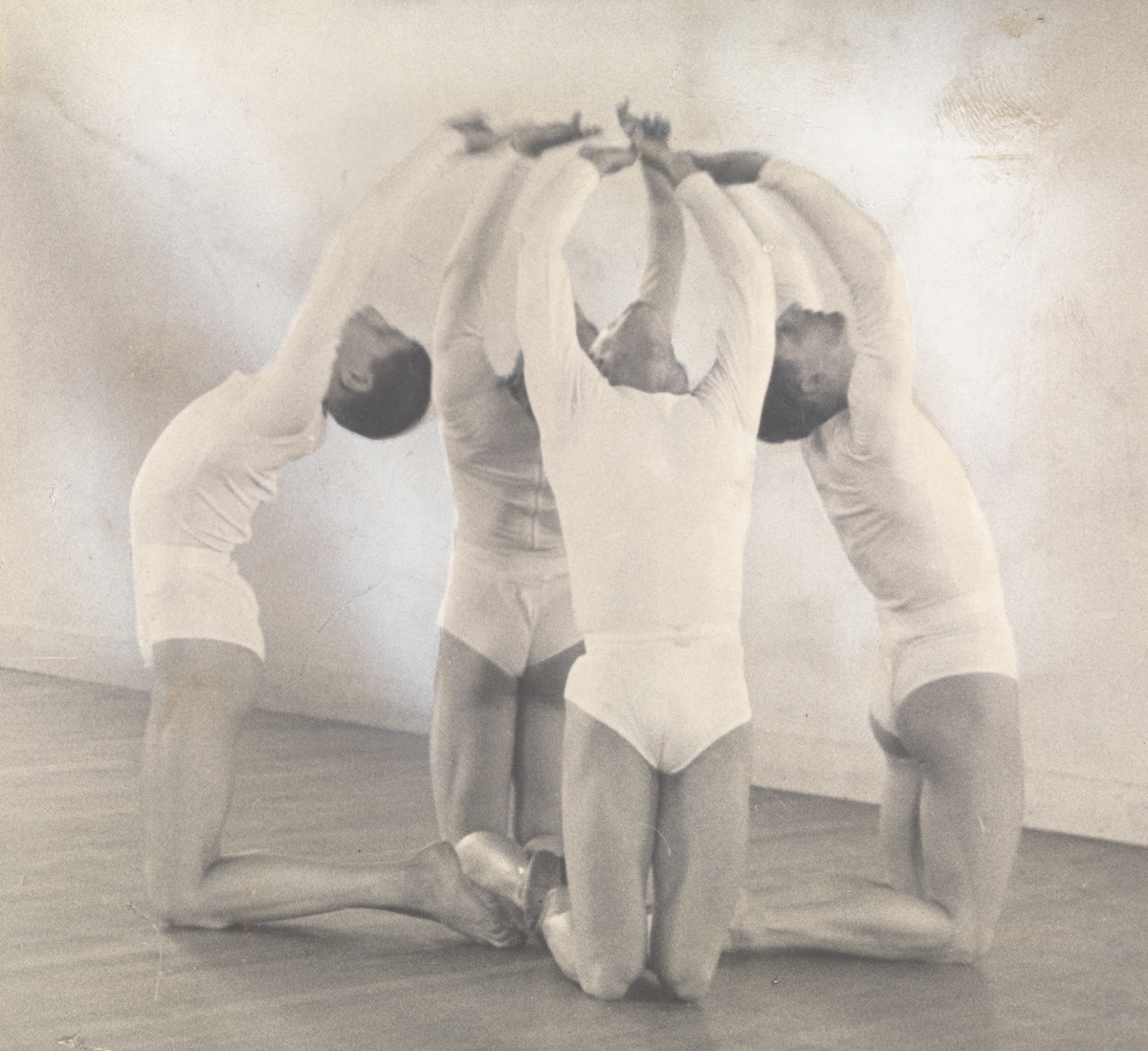

Much of Shawn’s choreographic output is marked by the performance of such stereotypically manly movement. In this excerpt from Kinetic Molpai, a dance inspired by ancient Greek ceremony, one can observe fists clenched in pugilistic form, broad-chested, decisive movements across space, and weighted, grounded call-and-response. There is plenty of gripping, hoisting and confrontational action. No sissies or “small scale movements” to be found here.

Shawn could be a paternalistic egoist, but he was a paternalistic egoist responsible for the launching of hundreds of dancerly careers, and catalyzed a near-century of institutional sustenance for work of men and women across color and cultural lines. This ambivalence can be read simultaneously with generosity and criticality, and arguably serves as an inflection point in a history of cultural gatekeeping and toxic masculinity as old as the western dance tradition. Shawn’s preoccupation with maleness and power resonates contemporarily in the struggles of such organizations as The New York City Ballet, which, at the time of writing, is grappling with the legacy of decades of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of male artistic directors. If there is any benefit to looking back at Shawn’s complicated legacy at this particular historical moment, it is with the hope that no dancer, choreographer, director, or administrator should ever be so beloved or so renowned as to absent the possibility of rightful criticism.

The legacy of Shawn continues healthfully in the form of the school and dance festival at Jacob’s Pillow, as well as its archives and grounds. Shawn’s repertory and imprimatur is resurgent as well. His dances have been performed with increasing frequency thanks to the close study, reanimation and interpretation by brilliant dancer / choreographer Adam Weinert, whose work is the subject of another essay in this series. Shawn has also entered the universe of contemporary pop-culture as a prominent character in Laura Moriarty’s bestselling work of historical fiction, The Chaperone, which has been filmed from a script by Julian Fellowes, the creator of Downton Abbey.Check out Variety for more information about The Chaperone The role of Ted Shawn is played by dancer and former New York City Ballet principal, Robert Fairchild.

PUBLISHED November 2018