Artistic Intent and Activism

Artists create their works for many reasons. Sometimes they create them for the sheer joy the process brings to them, and at other times they create because of their desire to help others understand the world they live in. In the end, there are probably many different reasons that coalesce to form the complex underpinnings of a work of art. As I continue to examine the work of African diaspora artists who have performed at Jacob’s Pillow for over eight decades, I find myself looking through archival material that, on the one hand, reveals each artist as a uniquely expressive individual; while, on the other hand, I find thematic material that attests to the common creative ground they share.

In tracing historical continuums, I know that part of what affects my work is that I find what I am looking for. That is, I am predisposed to interpret archival material based on a wide array of information that I bring with me to any given project. That includes, of course, information drawn from my prior work. For example, my earlier mention of sociological positivism—a construct promoting racial uplift through artistic pursuits—is an idea that I came upon when I was writing about African-American artists such as Hemsley Winfield and Edna Guy who worked during the Harlem Renaissance.John O. Perpener III, African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Chicago and Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001), pp. 15-16. The idea continues to fascinate me, in spite of its outmoded ideology of racial determination. Likewise, my mention of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s relates to my ongoing research of artists who were influenced by the black nationalist ideology of the time.

Other factors, however, help allay concerns I might have about the impartiality of my approach to archival research. Over the past three decades, scholars and historians of African diaspora dance have contributed to a growing body of literature that focuses on the lives and artistic careers of black dancers and choreographers. Consequently, one can find biographies, autobiographies, theoretical studies, and other scholarly works that relate African diaspora dance to a number of fields—sociology, anthropology, and musicology, to name a few. (During my current research, I was happy to find many of these books in the Jacob’s Pillow Archives.) Because of the increased number of individuals who examine black artists’ personal histories and aesthetic concerns, as well as the broader issues that impact artists’ work, a body of knowledge has been established that can be used to reinforce ideas that might have formerly seemed to be unsubstantiated thoughts of an impartial mind. Dance historian Jacqui Malone alludes to this body of knowledge when she refers, for example, to an idea that may have been debated in the past but is now generally accepted:

Recognition of the strong relationship between the dances of traditional African cultures and the dances of black Americans is now a commonplace among students and scholars of American history, music, and dance.”

The words of Brenda Dixon Gottschild—another scholar who has made invaluable contributions to this area of study—are clearly congruent with Malone’s thinking. Gottschild says, “African-based cultural forms and practices in the Americas can be traced to Central and West African traditions and have signposts that differentiate them from European-based forms and practices.”Brenda Dixon Gottschild, Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts (Westport CT, and London: Greenwood Press, 1996) p. 7.

Gottschild goes on to discuss the differences between European-based dance forms and African-based dance forms:

In traditional European dance aesthetics, the torso must be held upright for correct, classic form; the erect spine is the center—the hierarchical ruler—from which all movement is generated. It functions as a single unit. The straight, uninflected torso indicates elegance or royalty and acts as the absolute monarch, dominating the dancing body. . . .

Africanist dance idioms show a democratic equality of body parts. The spine is just one of many possible movement centers; it rarely remains static. The Africanist dancing body is polycentric. One part of the body is played against another, and movements may simultaneously originate from more than one focal point (the head and the pelvis, for example).Ibid, p. 8.

These ideas set forth by Malone and Gottschild, as well as those of other scholars, serve as an intellectual foundation that others can build on to insure that the stories of black artists are included in the literature of Dance Studies.

One of the recurrent themes of these artists’ stories revolves around the question I alluded to above: Why do artists set out to create their work? In the series of essays I have undertaken for this project, I emphasize the idea that the African-American, African, and West Indian artists who have performed at Jacob’s Pillow were often committed to use their creative efforts for social and political purposes as well as aesthetic ones. For example, Pearl Primus clearly voiced that type of intent when she said, “I started to dance because I wanted to show the dignity, and the beauty, and the strength, and the heritage of my people.”Spider Kedelsky, Interview with Pearl Primus, African Dance and Music: Sylvia Ardyn Boone and Pearl Primus, July 24, 1987, Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

A Brief Look at Revolutionary Dancers in New York City

When Pearl Primus began to be recognized as an emerging artist in the 1940s, political and social activism was an established practice among dancers and choreographers in New York City. In her book, Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928-1942, dance historian Ellen Graff traces the different forms this activism took as it evolved over the decades. Graff sets the artist/activists’ stories within the tumultuous contexts of the time, including the Great Depression that began in 1929 and the rise of Fascism that swept Europe during the 1930s. She also notes the demographic factors that affected the activism, “An overwhelming percentage of those involved with the revolutionary dance movement in New York City were children of mostly poor Russian Jewish immigrant families. . . . A resurgent racism, directed against blacks, but also against non-Nordic Southern Europeans such as those from Slavic and Southern European countries created a climate vulnerable to anti-Jewish agitation.”Ellen Graff, Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928-1942 (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 1997), p. 19.

As Graff points out, Edith Segal was one of the earliest activists to use dance performances for the sole purpose of achieving social and political objectives. Those objectives included employing dance as an educational tool that could bring ideas concerning class warfare to working class audiences. Segal also used workers themselves as participants in performances, so that they could “express ideas of social importance and revolutionary significance.”Ibid., p. 35. Like-minded artists created dances for worker-sponsored events, at Communist rallies, and at union gatherings.

Graff also discusses the schisms that developed between artists who privileged the political and social impact of their work and those who believed that concert dance should maintain a standard of technical skill and aesthetic refinement that was beyond the purview of amateur performers who were recruited for political gatherings. Graff singles out the New Dance Group—along with another important activist/artist of the 1930s, Anna Sokolow—as being instrumental in combining a higher level of dance expertise with sociopolitical content:

For Sokolow and members of the Theatre Union Dance Group and dancers of the New Dance Group, despite their deep commitment to political issues, the embryonic modern dance was first an art form and only secondarily an instrument of social change. These dancers took the charged political atmosphere of the 1930s as fodder for artistic ambition. In many cases their impression of political issues was emotional and intuitive, but the dances always reflected their need to understand and communicate. What established their credentials as revolutionary artists was the content of the dances, the political and social commentary that emanated from the percussive thrust of a heel or a head’s abrupt turn.Ibid., p. 75.

It is noteworthy that the artists who were at the forefront of political and social activism during the 1930s and 1940s were not frequent participants at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. However, there was one artist, Helen Tamiris, who was on the activist scene and also appeared at the Pillow.

As Graff explains, Tamiris was not associated with the militant dance groups of the time, but she was active in organizing projects that benefited the larger dance community. She was also instrumental in organizing the short-lived Federal Dance Project as a part of the U.S. government’s Works Projects Administration (WPA) which was designed to create employment opportunities for Americans during the Great Depression.Ibid., pp. 76-77.

Tamiris and her husband, Daniel Nagrin, appeared at Jacob’s Pillow on August 20 through 22, 1942 and performed a duet, My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free. Additional program information stated that the work was from Liberty Song, a ballet based on Songs of the American Revolution.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Theatre—Seventh Program—August 20-21-22—1942. The same program featured a work by Don Oscar Becque, who had served as the director of the Federal Dance Project at its inception in 1936. His contribution to the Pillow program was The Banner at Daybreak.Ibid. Anna Sokolow later presented her work at the Pillow on August 24 and 25, 1956, when her Theatre Dance Company performed Poem.Program, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival—Fifteenth Season—1956.

African-American Dancers’ Diverse Activism

During the late 1920s through the early 1940s, African-American dancers comprised only a small percentage of New York City’s most active revolutionary dancers—those who participated in worker-sponsored events and political rallies. The exceptions were artists such as Allison Burroughs who performed with Edith Segal in a duet originally titled Dance of Solidarity. The work was based on the idea that black and white workers should join forces to combat their oppression, and it was first performed at a mass meeting for International Women’s Day in March 1930.Susan Manning, Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Race in Motion (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), p. 71. Dance historian Susan Manning makes a persuasive case as to why Segal later changed the duet’s cast to include a white male dancer, first Hy Boris and later Irving Lansky, and a black male dancer, Add Bates. Manning suggests that Segal very likely felt that the male performers fulfilled leftist assumptions that the universal representation of workers should be a masculine image.Ibid. pp. 71-73.

In this series of essays, I discuss a later generation of African-American dancers who actively participated in political events in instances such as Donald McKayle’s performance at a benefit in support of the blacklisted actor/singer Paul Robeson.

And, it is important to remember—though I did not mention the point in her essay—that Pearl Primus also performed at mass political rallies. Author Susan Manning observes that the artist danced before twenty thousand spectators at the Negro Freedom Rally on June 7, 1943 at Madison Square Garden, and the program included appearances by Paul Robeson, Canada Lee, and Duke Ellington.Susan Manning, Modern Dance, Negro Dance, p. 168-169. Manning goes on to say, “Just two weeks before her Broadway debut, Primus performed at a rally celebrating ‘the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Communist movement in America’ held on September 28, 1944 at Madison Square Garden.”Ibid., p. 169.

One of the most fascinating and informative sections of The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus by Peggy and Murray Schwartz is the section delving into how the Federal Bureau of Investigation closely surveilled Primus’ every move during the years 1943 and 1944. In their attempts to gather information about her suspected affiliation with the Communist Party, the FBI documented where she performed, where she traveled, with whom she met and communicated, and other details of her daily activities. Authors Peggy and Murray Schwartz reference the extensive dossier that was kept on the artist, including the FBI informants’ documentation of Primus’ statements that equated the fight against Fascism abroad with the fight against Jim Crow racism at home in the U.S.Peggy and Murray Scwartz, The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 64-68. For example, the FBI files included a statement Primus made that was published in the Daily Worker: “I am only attempting to present the Negro in his own true light, as he was in the past in Africa and as he is now, a member of a fighting democracy. . . . We will never relax our war effort abroad but we must fight at home with equal fierceness. This is an all out war; we will not stop fighting until everyone is free from inequality.”Ibid., p. 67. Primus’ strident words shed additional light on the deep convictions she felt when she first visited the Pillow in 1948.

Katherine Dunham was another important artist whose life’s work was an indissoluble synthesis of art-making, social and political activism, and humanitarian engagement. Her activism took many forms, but one of the primary differences between her and the revolutionary European-American dance artists of the 1930s and 1940s was that she had to wage a constant battle against racist practices when she sought accommodations for herself and her company members as they traveled. In other essays in this series, I have shared some of the stories of the logistical problems that faced black artists who were seeking a night’s lodging or a warm meal. In this sense, their day-to-day existence often included an element of protest.

Katherine Dunham endured pressure from U.S. government agencies that questioned the political ramifications of some of her work.Like Primus, Dunham also endured pressure from U.S. government agencies that questioned the political ramifications of some of her work. One such incident occurred when her company premiered Southland in Santiago, Chile in January 1951. Dance historian Constance Valis Hill, in her thorough examination of the significance of Southland, reminds us that the 1950s was a decade when the Cold War, a new Red Scare, and the politics of anticommunism were powerful factors that led to the categorization of many liberal social causes as being subversive.Constance Valis Hill, “Katherine Dunham’s Southland: Protest in the Face of Repression,” in Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Thomas DeFrantz, ed. (Madison, WS: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002), p. 289. Works of art, and the individuals who created them, were not exempt from examinations by U.S. government officials. The premiere of Southland came under scrutiny because the American Embassy in Chile felt that the ballet’s incendiary subject matter would cast an extremely negative light on the history of race relations in the United States. The work was set in the South, and it recounted the events that led up to a black man being lynched, including a false accusation of rape by a white woman. Many of the narrative’s violent events were enacted with intensely dramatic dance movement and mime, including a graphic depiction of the lynching.

Constance Valis Hill goes on to discuss the negative consequences that impacted Dunham’s professional career after she premiered the work in Chile, knowing that diplomatic officials were opposed to it. Due to pressures from the U.S. State Department, there was minimal coverage of the work in the local press, and the Dunham Company was forced to leave Chile a few days after the concert. Southland was not performed for the balance of the South American tour; however, it was presented in Paris in January 1953. At that time, it received some favorable reviews, but there were also those commentators who complained, because they only wanted to see the Dunham Company perform the kind of exotic and entertaining material they had become accustomed to during the group’s previous tours.Ibid. pp. 304-306.

After Dunham revived Southland in Paris, she never presented the work again, but Hill notes that the tensions surrounding her company’s South American and European tours during the 1950s led to permanently strained relationships between her and the U.S. government, as indicated by the State Department’s refusal to include her company in their early initiatives that sponsored dance companies to travel abroad as artistic ambassadors of American culture. This support was eventually extended to the companies of José Limón, Martha Graham, and Alvin Ailey. However, the lack of government support for Dunham played a large role in her decision to disband her company in 1965 because of financial problems and because of sheer exhaustion from the myriad pressures of running her company.Ibid. pp. 309-310.

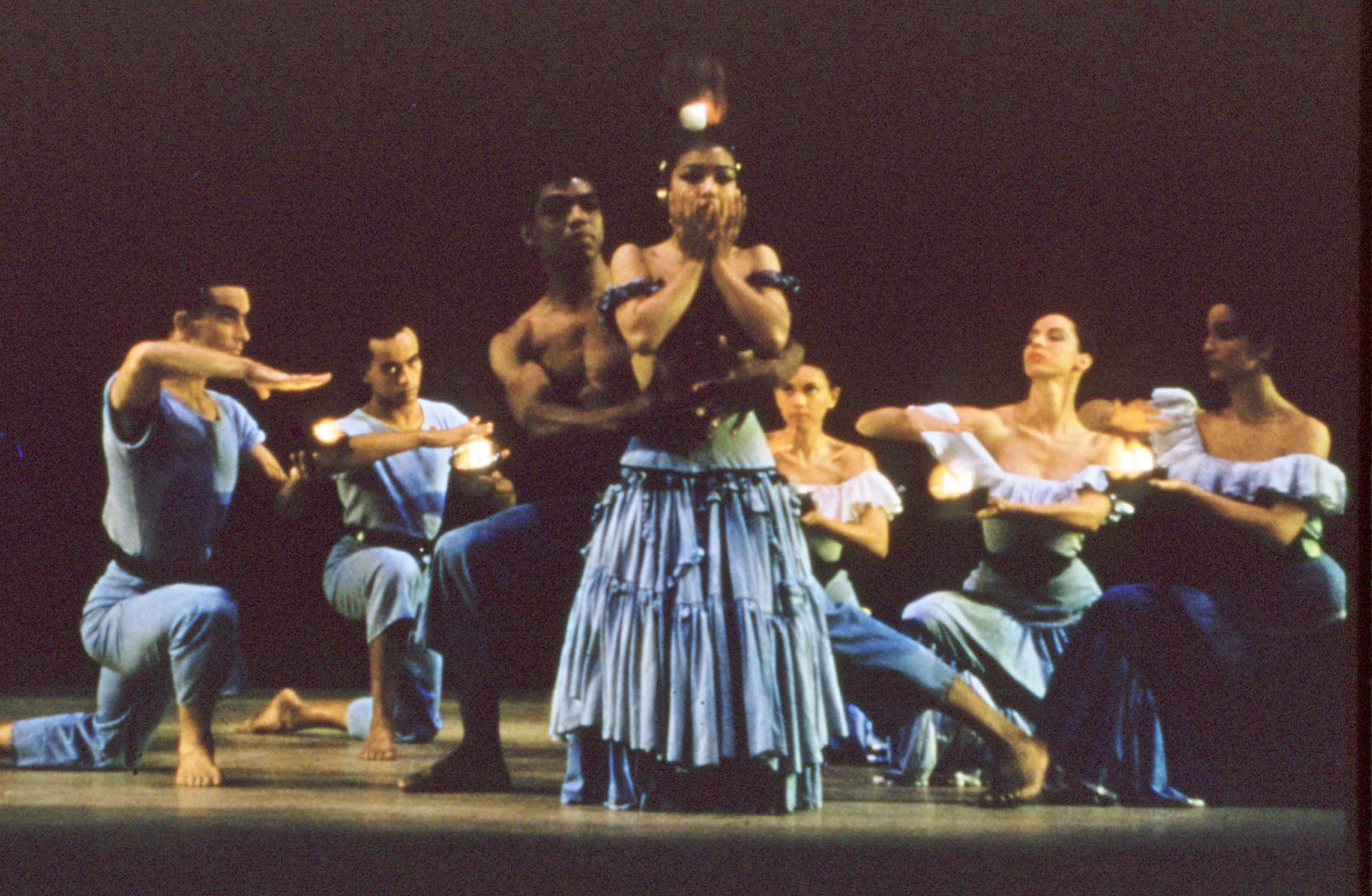

Dunham’s commitment to pursue her art, battle for social justice, and engage in educational and humanitarian projects is a story that is beyond the scope of this essay, but her incalculably rich contributions through a wide array of endeavors certainly led to her being honored at Jacob’s Pillow on June 24 through 27, 2002. While she never performed at the Pillow, a letter from Dunham in April 1947 answers an invitation that had been issued two months earlier, stating “I have wanted to appear at Jacob’s Pillow for a long time but find it impossible to make a definite commitment.” Even so, A Tribute to Katherine Dunham was a homecoming in the sense that former company members, friends, and supporters gathered to celebrate her phenomenal life. The gathering included a younger generation of dancers who took classes, performed, and attended lectures and seminars.

Former company members present included Walter Nicks and Julie Belafonte (who, decades earlier, had performed the role of the white female accuser in Southland). Among the groups that performed on the closing concert were the Pan Caribbean Dancers, the Ghana Dance Ensemble, Ballethnic Dance Company, and Ronald K. Brown/ Evidence, and the speakers that evening included Harry Belafonte and Danny Glover.Program, A Tribute to Katherine Dunham, June 24, 2002, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Dunham was, of course, the pivotal force at the center of the activities that included a celebration of her ninety-third birthday.

She also had the opportunity to reflect on her life and her career in a PillowTalk, where one member of the audience asked what it had been like to dance against racism. She answered in her inimitably direct way:

It was at sometimes not easy at all. But, let me tell you something. If we’d be perfectly honest about it, it was a good thing. It gave me impetus. It aroused my adrenaline; and, uh, gave me a focal point that I might not have had, had I been just one of those, you know, pale-faced, easy-going people. I always had something to fight for, and I thank racism for that. I don’t thank it for what it’s done for some people who haven’t been able to rise up and above it. But, for those of us who’ve been able to stand up and say “fuck it,” we made it . . . . Sorry, you know, sometimes there are no words except the “word.”Katherine Dunham, Pillow Talk, moderated by Reginald Yates, June 22, 2002, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

Her comments resonate with a point I made earlier concerning the difference between the protests of European-American artists and those of African-American artists who had different battles to fight. She validated her work—and that of other black artists—by embracing the racial conflicts that made her fight even harder to achieve her goals.

In addition to outspoken artists like Katherine Dunham and Pearl Primus, I believe there have also been black artists whose creative efforts have had sociopolitical impact whether they clearly intended it or spoke of it at all. In other words, I believe that the very nature of black artists’ historical struggles to present their work in mainstream venues has often been motivated by their sometimes silent determination to gain entrée into artistic arenas that have been surrounded by racial proscriptions. In this sense, their work accrues social and political overtones whether that is their stated intention or not.

Alvin Ailey was not as forthcoming about the social and political intent of his dances as artists like Primus and Dunham.In my book, African-American Concert Dance, I use Alvin Ailey as an example of the type of artist who was not as forthcoming about the social and political intent of his dances as artists like Primus and Dunham were. With the exception of Masekela Langage—his commentary on apartheid in South Africa—Ailey created few dances that included intentional sociopolitical messages. I proposed a different way of looking at the political impact of Ailey’s work:

The political nature of Ailey’s work lay in the effect that it had on reshaping the aesthetic paradigms of those who saw it. It forced critics and audiences to broaden their perceptions of art and consider with new eyes the possibility that African-American dance could be cast in the mold of serious art. By valorizing his African-American cultural heritage and challenging existing aesthetic hierarchies, Ailey was effectively usurping the social and political power that was attached to privileged categories of art and claiming it as his own.John O. Perpener III, African-American Concert Dance, p. 201.

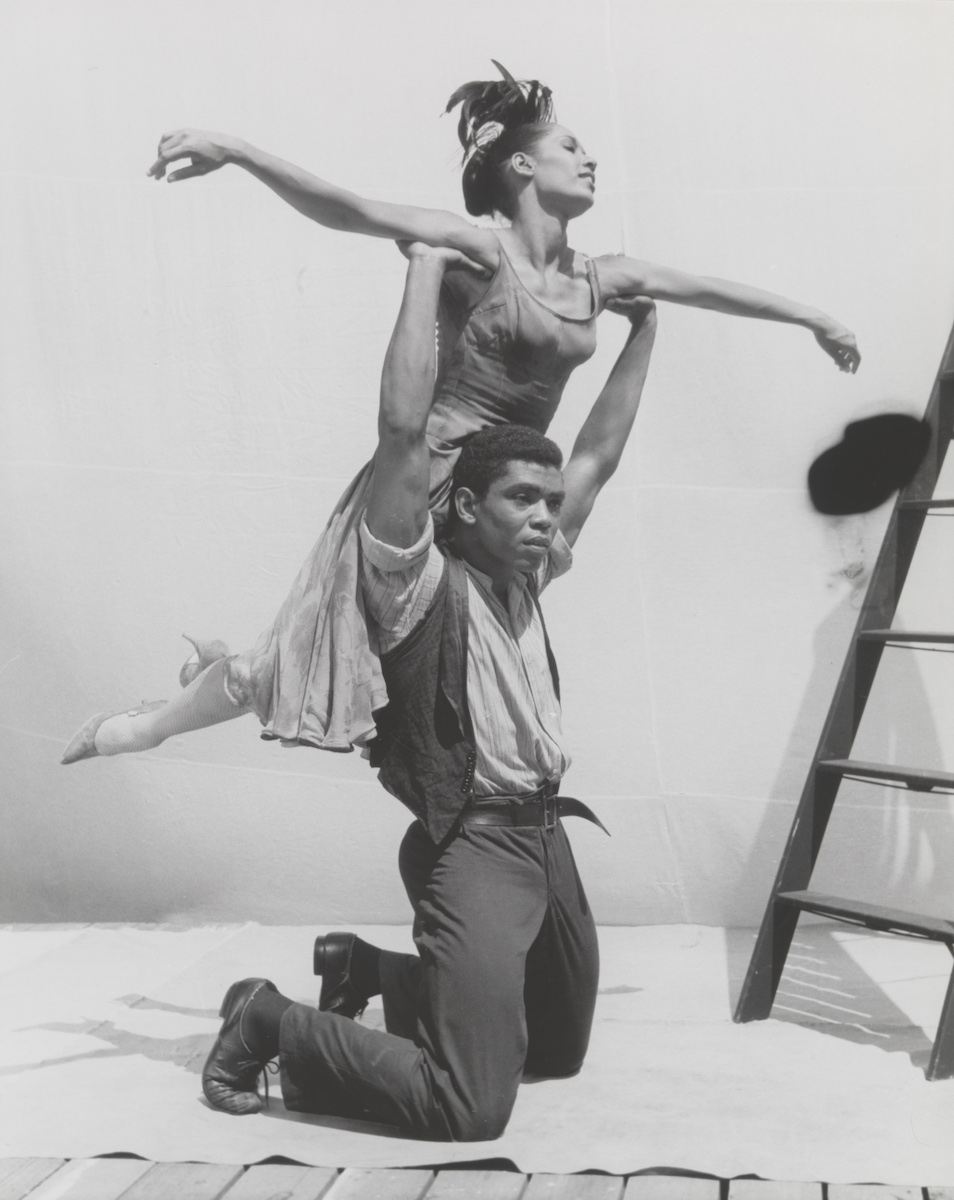

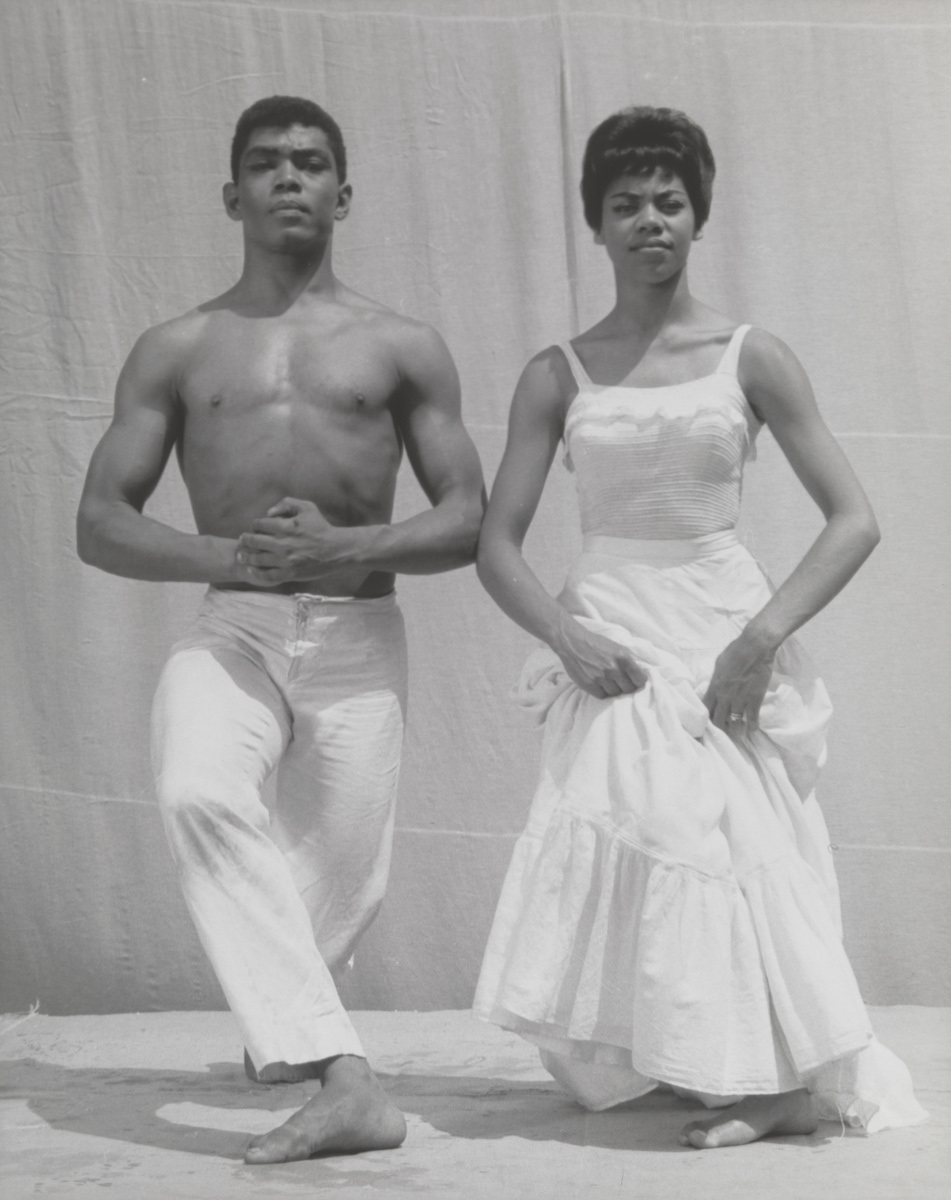

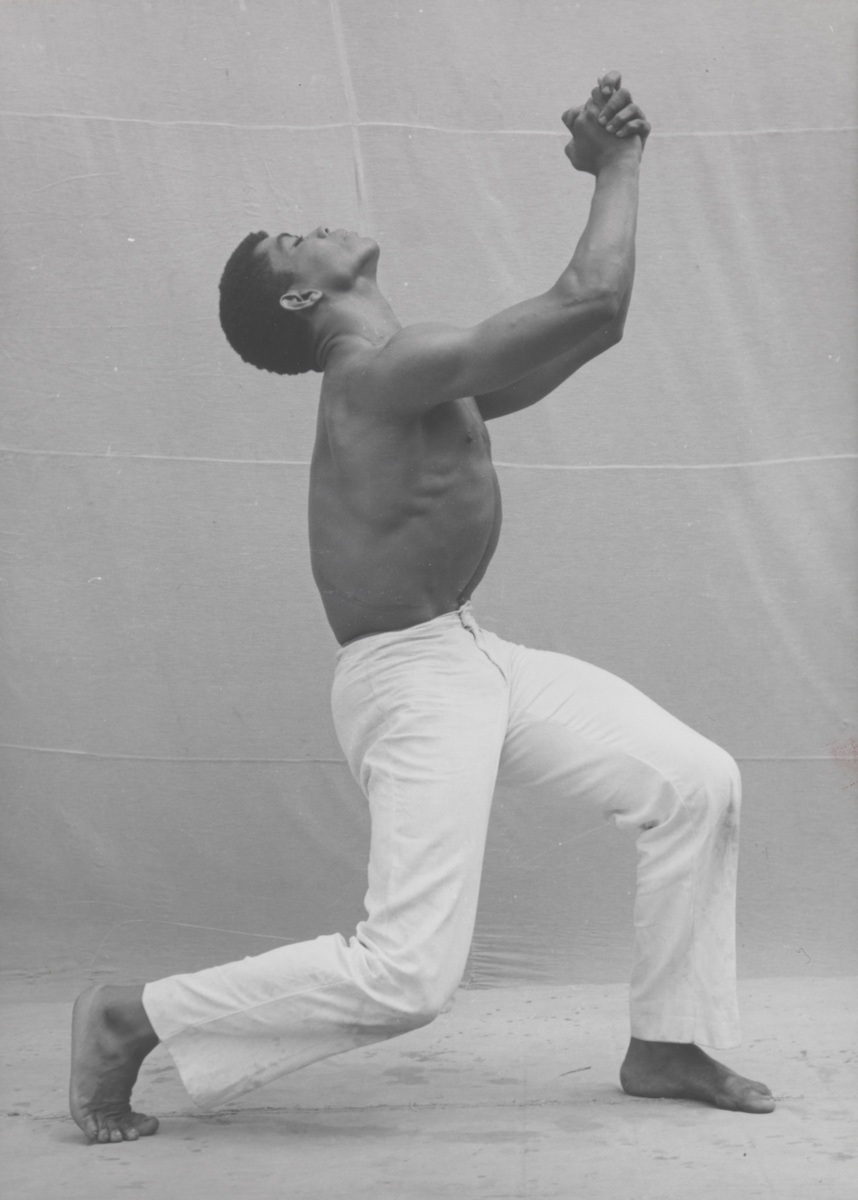

Ailey began his association with the Pillow when he first visited the festival in 1954 with the Lester Horton Dance Theater.

When the company performed on July 22 through 24, Ailey presented one of his earliest choreographic undertakings, According to St. Francis. His first exposure on the east coast was not, however, warmly received by critic Walter Terry who found Ailey’s choreography naïve and poorly developed, while Ted Shawn felt that the young artist knew nothing about choreography.Jennifer Dunning, Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1998), p. 77. Those initial negative reactions were eventually smoothed over, and Ailey’s company returned several times over the years, beginning with their June 30 through July 4 performances in 1959. At that time, they performed Blues Suite, bringing Ailey’s colorful and theatrical dance aesthetic to audiences in the Berkshires.

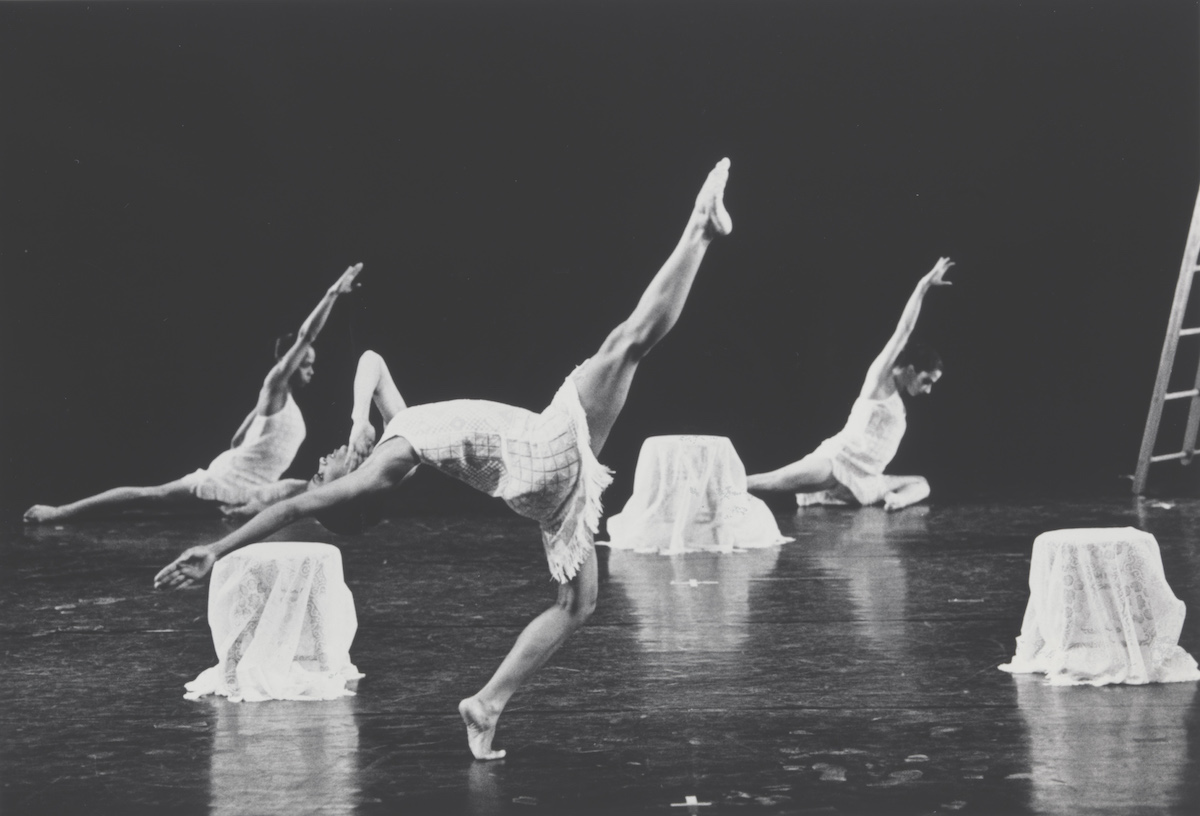

During the company’s next visit to the festival, July 18 through July 22, 1961, Ailey presented his most iconic work, Revelations.

The company’s other appearances occurred during the summers of 1963 and 1988; and the festival played an important role in their development, as it had in the maturation of other fledgling dance companies over the years. Moreover, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater went on to become a foremost arts institution, representing the uniqueness of American culture to diverse audiences. In works like Blues Suite and Revelations, Ailey summoned his exceptional creative energies to present his vision of African-American cultural heritage in national venues like the Ted Shawn Theatre and on stages around the world.

It is apparent that Ailey’s artistic trajectory shares common elements with other choreographers discussed in these essays. I have discussed Pearl Primus’ Strange Fruit and Hard Time Blues, Talley Beatty’s Southern Landscape, Donald McKayle’s Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder, Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s Praise House and Joanna Haigood’s Invisible Wings. The artists purposefully used their choreography to tell the stories of African Americans who survived under the pressures of America’s unique racial constructs. It follows that they would create a kind of dance theater that privileged narrative structures, as it recounted particular times, and places, and events. Their choices of subject matter and use of narrative appear as a strong common denominator that has been revealed at Jacob’s Pillow over the decades. Consequently, I can extrapolate that the slaves who fly away in Haigood’s Invisible Wings are related to the mischievous angels that haunt Hannah in Zollar’s Praise House. I can see that Primus’ Strange Fruit and Dunham’s Southland are cut from the same cloth. Such observations are not an attempt on my part to force the artists into a kind of essentialist mold. It is simply to acknowledge a tradition of African diaspora storytelling through concert dance that was brought to the Berkshires over a period spanning eight decades.

PUBLISHED November 2017