Introduction

In daily life, one may experience the trend of bearing witness and responding to an action or behavior—this happens every second of every day when people ‘call-out’ one another on social media. “Call-Out” culture was a term coined several years ago by Amsterdam writer and media analyst, Flavia Dzodan, that sparked fire under the online feminist revolution. This popular term has become a way to define how activists, bloggers, academics, and any social media user can publicly condemn language, actions, or behaviors that they find insensitive or hurtful to themselves or others. Some find the practice of “calling-out” to be toxic, while others see it as a way to combat social justice issues. Poet Asam Ahmad wrote, “Call-out culture can end up mirroring what [we are taught] about crime and punishment: to banish and dispose of individuals rather than to engage with them as people with complicated stories and histories.” Asam Ahmad, “A Note on Call-Out Culture,” Briarpatch Magazine, March 2, 2015. It is that complexity of collective history, housed in the body, that we explore in this essay, as we ‘call-out’ what would be potential points of friction that come together through movement.

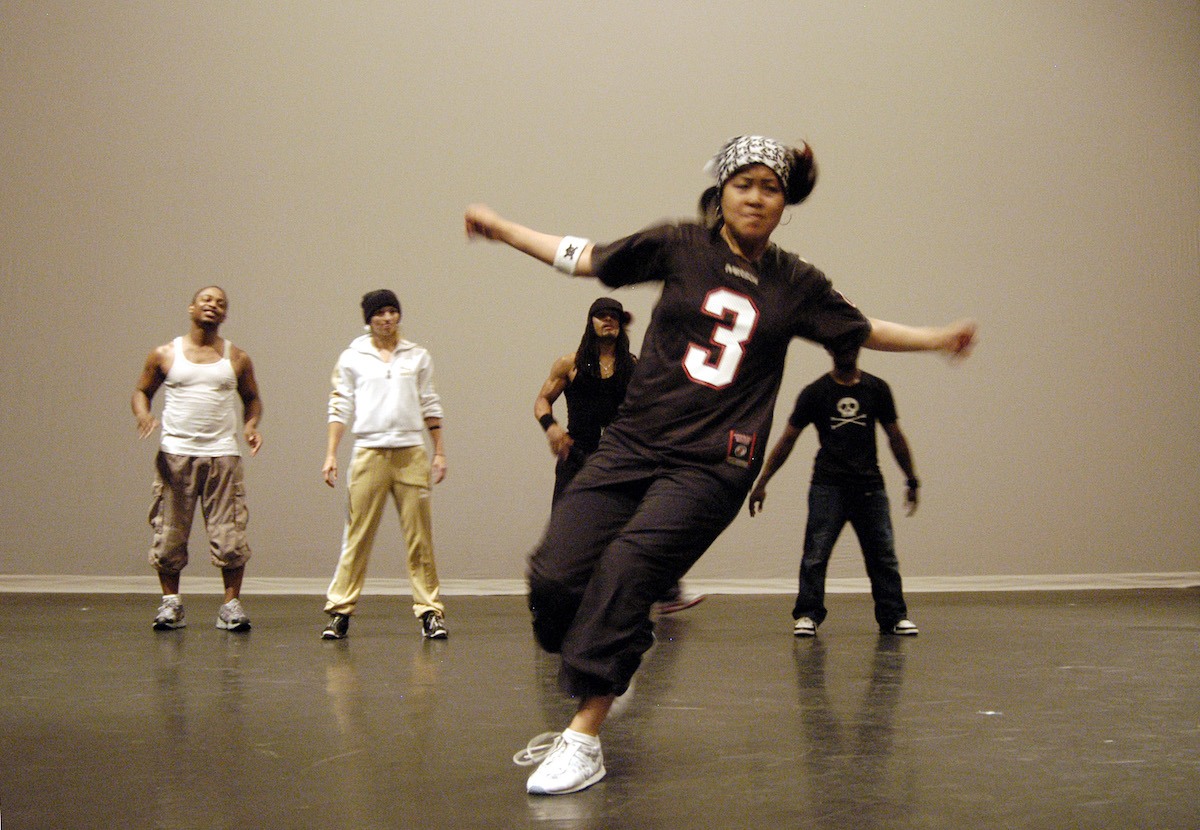

For a dancer, the moment of the physical call and response can be found in various movement lineages. We are all trying to remain authentic to the historical and cultural movement forms which we’ve spent most of our lives training and studying, but are simultaneously on a path to find what makes us unique as artists.As both a street dancer and contemporary dancer, I have witnessed the way that we are all called upon to “show and prove” in the classroom, concert stage, or the cypher: an open circle of call and response where dancers take turns expressing improvisational vernacular movement vocabulary. We are all trying to remain authentic to the historical and cultural movement forms which we’ve spent most of our lives training and studying, but are simultaneously on a path to find what makes us unique as artists. The very definition of “authentic” in the Merriam Webster dictionary illustrates the duality of the word: “Made or done the same way as an original; AND true to one’s own personality, spirit or character.” As an artist that uses street dance forms on the concert dance stage, I’ve had to make some thoughtful decisions when traversing the space between community validation and fear of said “call-out,” as well as artistic freedom. Even though these two concepts attempt to co-exist, there will always be areas of friction whether physical or metaphoric, especially if we observe the body as a living, breathing, changing document.

So what happens when a body that is steeped in rich cultural and historical movement traditions begins to venture out of the original blueprint in an attempt to find their “authentic” language? Or what happens when “authentic” movement is put on bodies that don’t speak that particular language? Are “call-outs,” whether online or in a physical space in this case, vital to keep that particular movement culture sacred? When does “calling-out” become toxic or intimidating to the makers of the work? These questions were discussed with choreographer, dancer, and colleague, Pillow Lab artist-in-residence Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie, during an interview in September 2017.

Ephrat Asherie

Ephrat describes her years of training in the New York City underground house and breaking scenes as she massages her hamstrings with a tennis ball, sore from an 8 hour rehearsal day. A story of her time with the late legendary NYC house dancer, Marjory Smarth, was the inspiration for the title of this essay, and reiterates the notion of the body as a living document or archive. Asherie passionately explained that “Marj” always believed that honesty in movement is the most important source of inspiration in your dance—honesty in this case being your cultural movement lineage, personal experience, environmental influences, and then dancing your truth in this ephemeral moment. Ephrat spent years pursuing the art of being honest not only in the clubs and breaking competitions of NYC, but also on the concert stage where she now directs six other bodies with diverse archives of their own in her new work, Odeon.

She chose these dancers because she said that they possessed a “lived-in-ness” that only comes from a strong improvisational practice in various forms of the African Diaspora. Asherie stated “we all speak the same language, but have different accents,” when describing the various authentic movement experiences embodied by each dancer, ranging from vogue to breaking to various African dance forms.

Ephrat’s relationship with Jacob’s Pillow has been symbiotic in that she has shown her work on the Inside/Out Stage in 2013, performed in Unreal Hip Hop the following year, was featured in Dorrance Dance’s ETM (in both 2014 and 2016), and has utilized the newly formed Pillow Lab to create new work for her company, Ephrat Asherie Dance. In her critically acclaimed and Bessie award winning performance with Dorrance Dance, Ephrat describes her training to be a cross-pollination of rhythm where the extraordinary tap dancers would exchange their “lived-in” percussive knowledge with Ephrat’s hard drive of embodied street dance forms. Her style, speed, and movement patterns have not only been influenced by her time with Dorrance Dance, but by b-boy mentor, Break Easy, and her work with two other Pillow-related artists, Doug Elkins and Rennie Harris.

Ephrat was able to articulate how Doug Elkins described the use of “sampling” in the body in relation to a graffiti wall. Ephrat explained that the observer may only see the top layer of the image, but all the layers of form and content are still there underneath. The metaphor of Doug’s graffiti wall concept connects to the idea of the body as a living, breathing document that contains knowledge which has been researched, proofread, and edited.

B-girls, Crossing Boundaries

When describing Rennie Harris’s work, Ephrat expressed that he was one of the first inspirations for her to create for the concert stage. As a b-girl (break girl) performing in the acclaimed Harris production Rome and Jewels, Ephrat experienced the challenging physicality that Rennie was able to clearly replicate from battles and cyphers to the concert stage. During the performance the audience was able to observe the execution of breaking vocabulary filtered through a female body. What the audience did not see was the additional process that Ephrat investigated for years prior to the performance, in which she navigated what her authentic masculine gendered expression and presentation of the dance would be, and how that language would be “called-out” from other b-boys (break boys) as well as the community.

Having trained in the b-boy vernacular myself, I have always attempted to articulate the additional process of deciphering and translating this movement language onto the female body until it feels honest, a task that most heteronormative b-boys generally don’t have to worry about. This filtering process takes several years to understand and investigate through the female body, and is a journey shared by a small group of warrior women who call themselves “b-girls.”

Wendy Whelan

We can also look to New York City Ballet principal dancer Wendy Whelan as a dissertation of performed truth. Her 2013 Jacob’s Pillow performance of Restless Creature brought together four contemporary male choreographers to collaborate on separate, diverse duets. Each duet explored the evolution of Whelan’s journey as a dancer in terms of concept and physical rigor, as well as contemporary forms of partnering. She carefully curated the younger contemporary male bodies to challenge her rehearsal process by filtering the new languages of these four men through her “lived-in” rubric of knowledge and experience. Her openness and willingness to translate these bodily archives to her own is exciting for the audience to witness, especially if they have followed her physical journey through her years as a ballet dancer. The difference for the viewer as compared to seeing Ephrat perform, is that the audience has a visual and kinesthetic memory of Whelan’s body from having access to venues where that body is publicly celebrated and supported. Audiences are able to understand and observe her language fluency over time, and then witness her attempt to speak in others’ dialects. In Ephrat’s work, the process isn’t as easily understood unless the viewer is privy to the sacred spaces of the underground street dance scene. The body’s connection to space acts as a sentence structure in which context becomes necessary to truly understand how the chapters of the body are written.

Queering Perception

The decoding of secret languages from private to public is a concept that is quite familiar to Erika Randall, a queer choreographer/filmmaker who is a professor and chairperson of dance at the University of Colorado Boulder. Randall explains that heteronormative spaces such as the symphony, opera house, university, or museum can be “bent” with subtlety to include elements of queer culture, sexualized gesture, and bodies that decode a secret language. We can witness these whispered (and screamed) ‘essays’ in the work of David Roussève/Reality, whose performance of Stardust at Jacob’s Pillow in 2014 took audiences into an intimate world of gesture, physicality, and body language that is rich with commentary on queerness, race, and generational gaps. In this work, the history of each diverse body was highlighted in relationship to technology and each other. The emotional body of each dancer took center stage, as the performers gave the audience access to sacred and intimate spaces that left us to ponder the emotional truth of our own bodies.

Being able to speak an honest truth in any space, means starting with comprehensive knowledge of a specific practice. Today you can walk past popular clothing stores and see shirts bearing slogans such as “Namaste Woke,” which makes a clever cultural pun from the Hindu word used as a salutation at the end of yoga classes, mixed with the urban vernacular of staying aware of what is happening around you. The sampling, blending, or in some cases appropriation of language and action can feel like a shallow attempt to show empathy. It seems that as a culture we have become consumed with “call-outs” rather than personal study and rigor, while we observe self-made Facebook and Twitter philosophers challenge us to find our authentic selves. Digging deep into sacred spaces, bodily archives, and personal authenticity is a practice that these incredible artists have chosen every day, and is also the reason that we as an audience can be inspired to create change in our society by starting with the daily ritual of choosing embodied truth.