Introduction

In 1945, Jerome Robbins wrote an OpEd for The New York Times in which he identified a significant shift in American dance: Ballet, which had been the “orchidaceous pet of the Czars,” as he described it, had found a new identity in the United States as “a people’s entertainment in our energetic land.” In other words, he said, dance didn’t have to be about swans and sylphs anymore—it could be about sailors and cowboys, too. Dance was becoming populist, and distinctly American. Robbins’ own ballet, Fancy Free, which came out a year earlier and had evolved into the hit Broadway musical On the Town, was a case in point.

A few years later, in 1949, Fancy Free came to the Pillow with the young American Ballet Theatre, sharing the line-up with founder Ted Shawn, Ruth St. Denis, and a dozen other dancers from a variety of styles. That example neatly illustrates how, from the beginning, the Pillow embraced all forms of dance, and dance for all audiences, with little regard to drawing firm lines between “orchidaceous pets” and “people’s entertainment.” As a result, the relationship between concert dance and musical theater dance has been fluid here—there’s a direct line from Jacob’s Pillow to Broadway. A proud one.

Jacob’s Pillow has long considered dance in musical theater an intrinsic part of the dance ecosystem. Though the festival has a reputation for bringing the world’s top ballet and contemporary dance companies to Becket, it has also been engaged in a vibrant two-way conversation with the Great White Way (so named in the 19th century because of the bright lights that illuminated the theater district). That has much to do with the artists themselves who, then and now, for both creative and financial reasons, have built careers that toggle between commercial theater and concert dance. Choreographers from Robbins and Agnes de Mille to Garth Fagan and Camille A. Brown have found success and built reputations in both communities, learning from and challenging the conventions of each.

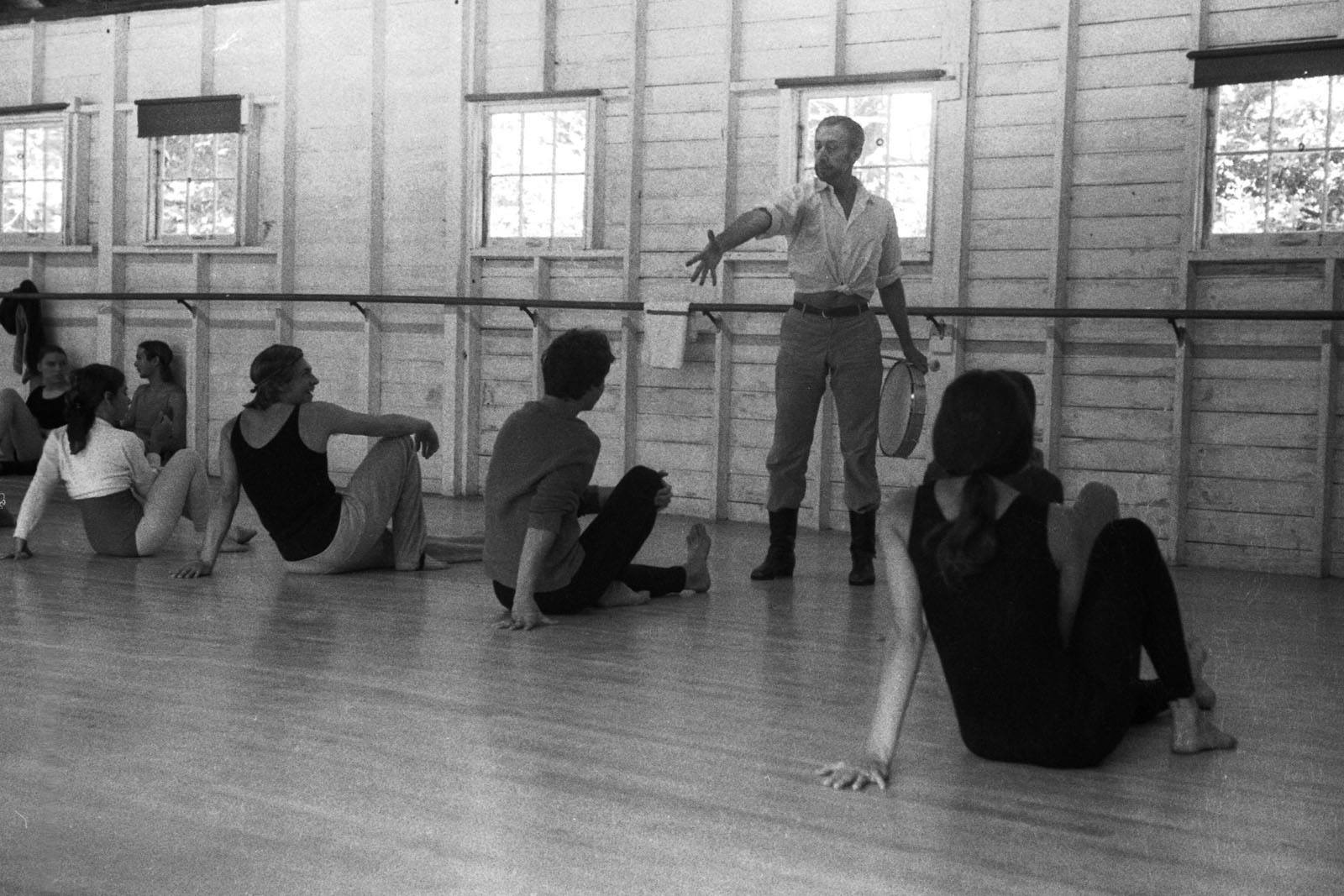

In particular, the School at Jacob’s Pillow has long sought to prepare the next generation of musical theater dancers for a robust career on stage by bringing some of the industry’s top choreographers to the festival to learn classic repertory from Broadway masters, while they are also surrounded by some of the most cutting-edge and experimental contemporary dance from around the country and the world. Those influences often bleed into one another, offering exciting possibilities for dance’s future.

In other words, Jacob’s Pillow has always put Broadway dance in conversation with other dance genres in a way that is rare and important. Musical theater dance tends to get unfairly separated from the pack, seen as a style in service to something other than itself—escapism, pure entertainment, not dance for dance’s sake—and one often caught in what some people see as the compromising glare of for-profit theater. But a look at the artists that Jacob’s Pillow has hosted since its founding in 1933 reveals that here, musical theater is part of the wider dance family.

Golden Age Pioneers

The Pillow’s relationship with Broadway can be traced back to the beginning. The Festival’s founder, Ted Shawn, was a mentor to many Broadway performers and soon-to-be stars. Among them was Barton Mumaw, an original member of Ted Shawn & His Men Dancers, who performed frequently at the Pillow in its first decades while also appearing in Broadway productions like Annie Get Your Gun and My Fair Lady.

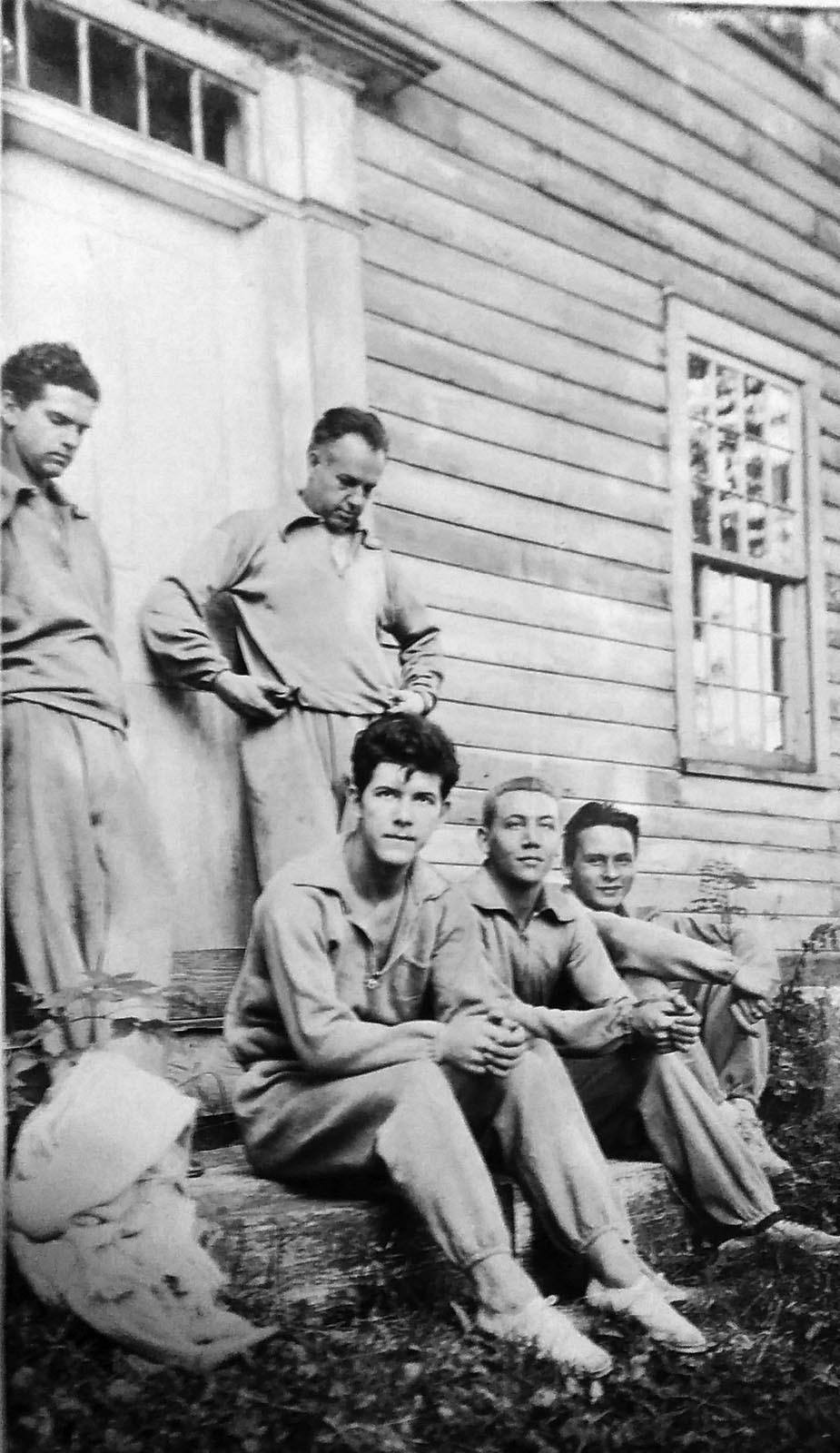

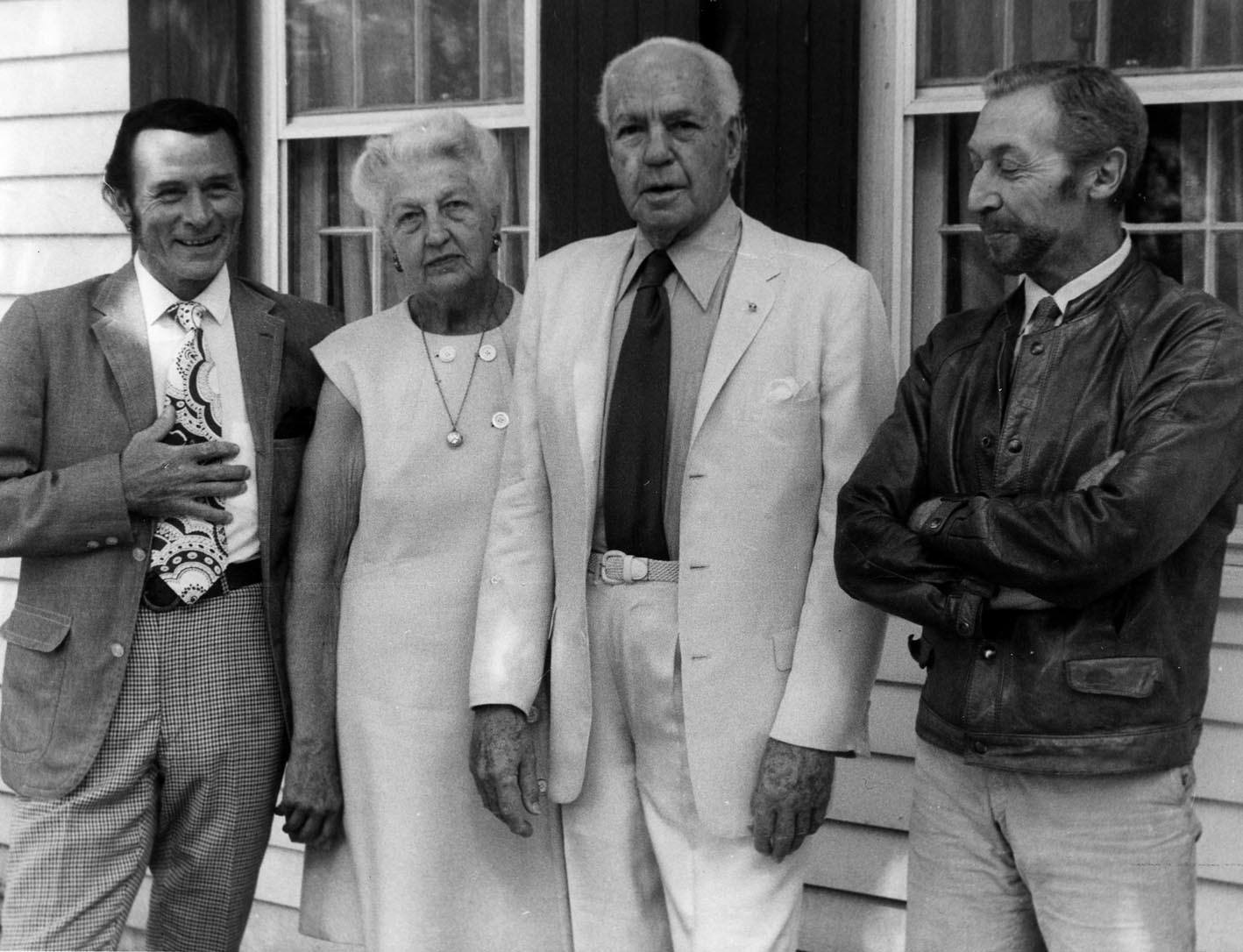

Another founding member of Shawn’s all-male troupe was Jack Cole, who helped Shawn transform the Becket farm into the dance center we know today, and performed here in the inaugural summer of 1933. But that affiliation didn’t last long, owing to artistic tensions between Shawn and Cole. Shawn’s troupe was intended to be an ensemble, but Cole wanted to be a star. In a 2010 PillowTalk, the Pillow’s Director of Preservation Norton Owen shared Shawn’s impression of Cole, as written in an unpublished section of Shawn’s autobiography. Cole, Shawn wrote, “was too much to cope with.” He made “everyone in the audience watch him.”

So Cole left the Men Dancers and the Pillow to immerse himself in all forms of dance. He launched a nightclub career and performed on Broadway before making the leap to Hollywood, where he became famous for his choreographic contributions to movies such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Some Like It Hot. After success out West, he returned to New York and worked prolifically in theater, choreographing shows like A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) and Man of La Mancha (1965).

But he maintained his relationship with the Pillow as well, returning to teach courses on American Theater Dance in 1971 and 1972. The fusion of modern dance with the intimate interactions of a cabaret paired with the polished glitz of Hollywood was a uniquely Cole concoction, and the influence of his eclecticism can be seen on screens and stages today, as well as echoed in the aesthetic of many artists that have passed through the Pillow and especially in the spirit of the students here.

Another influential choreographer to visit the Pillow on multiple occasions in its first decade was Agnes de Mille, one of the 20th century’s most famous theater choreographers. De Mille made her Pillow debut in 1941 (with Ballet Theatre), several years before she revolutionized dance on Broadway with her game-changing ballets for Oklahoma! (1943) and Carousel (1945) that positioned dance as a tool of storytelling, rather than a mere decorative pause from the plot.

As mentioned, Robbins’s work was performed here in 1949 by Ballet Theatre. Robbins would go on to become probably the most successful choreographer to conquer both concert and commercial dance as a co-director of New York City Ballet and the man behind the moves of West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof, among other stage classics. In 2014, 65 years after Fancy Free was first performed at the Pillow, Stars of American Ballet, a traveling troupe comprising mostly members of City Ballet, brought the work back to Jacob’s Pillow just months before On the Town was revived on Broadway (in a production that had originated nearby at Barrington Stage), illustrating just how close the Berkshires and Broadway have remained throughout the years.

“[He] made us build an intellectual architecture for what was happening. It wasn’t about feeling, it was about being there.”In a 2018 PillowTalk celebrating the centennial of Robbins’s birth, the ballerina Wendy Whelan recalled working with the master as a young dancer at City Ballet and his insistence, even in the abstract world of ballet, on finding a sense of place and character in dancing—characteristics of theatrical dance. “He made us think about the surroundings of our dance, as a person,” Whelan said. “[He] made us build an intellectual architecture for what was happening. It wasn’t about feeling, it was about being there.”

Other legends of Broadway have made their mark on the Pillow as well. The choreographer and director Gower Champion, known for classics like Bye, Bye Birdie and 42nd Street, had a Pillow connection through his longtime wife and dance partner, Marge Champion, a Pillow board member and frequent presence at the festival for more than 30 years. Their son was the namesake of Blake’s Barn, home to the Jacob’s Pillow Archives and numerous Broadway-related exhibitions, and in 1986, Blake danced with his mother in a Pillow Gala “Tribute to Gower Champion” to music from perhaps Champion’s biggest hit, Hello, Dolly!

Like Champion, Bob Fosse, whose stylized hips and hands radically changed Broadway movement in shows like Pippin and the film of Cabaret, never visited Becket, but his work has been performed here, notably in 1987 when Ann Reinking, one of his muses, performed Big Noise From Winnetka with Gary Chryst, which had been seen on Broadway in the show Dancin’. On three other occasions in the 1980s, Reinking returned to teach in the school’s Jazz Project. Fosse’s work also came to the Pillow in 1992 compliments of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, which performed his short, snappy Percussion Four.

In 2001, Chet Walker, the head of the School at Jacob Pillow’s Musical Theater Program and a veteran of several Fosse productions, gave an informal talk to students in which he relayed anecdotes about Fosse’s famed temper, idiosyncrasies and physical genius. “Nothing was ever right. Nothing was ever finished. Nothing was ever perfect. All things could be better,” Walker recalled. He went on: “A lot of people said he was ahead of his time and I think sometimes when people say that it’s because they can’t categorize you.”

Cole, de Mille, Robbins and Fosse: These giants of 20th century musical theater dance ensured that entertaining theatrical dance had a place at the Pillow even as the majority of companies presented here fall into the categories of ballet, modern, and contemporary dance. But that ongoing dialogue is an important part of the ethos of the Pillow, one that continues with a new generation of dancers who refuse to pick a side and instead seek multi-faceted careers combining concert and commercial work.

The Modern Revolving Door

All of the previously mentioned choreographers have passed away, but it’s clear they influenced several generations of broad-minded and curious dance-makers who don’t see borders between creating an evening-length dance piece and contributing to the storytelling of the theater.

Take Twyla Tharp: Tharp started creating quirky experimental dances for her company in 1965, and the troupe made its Pillow debut in 1973—the first of five appearances. Tharp went on to choreograph the 1979 film adaptation of the counter-culture musical Hair and in 1980 made her Broadway debut with When We Were Very Young. But it was in 2002 that she really welded the worlds of concert dance and Broadway with the acclaimed, genre-busting show Movin’ Out, an all-dance interpretation of Billy Joel’s music.

A year after Tharp first came to the Pillow, a company called Bottom of the Bucket But… Dance Theater made its debut here. That company was run by Garth Fagan, a spirited choreographer known for blending modern dance with the Afro-Caribbean rhythms and techniques of his home country, Jamaica. Since then, iterations of Garth Fagan Dance (as it’s now known) have been presented by the Pillow 10 times. In between, Fagan became internationally known for his Tony-winning choreography for the long-running smash Disney musical, The Lion King.

In a 2000 PillowTalk called “Barefoot to Broadway,” Fagan spoke with scholar Suzanne Carbonneau about the differences between making dance for his own company and collaborating with a director on a huge theater production. “In my own company, I call all the shots,” he said. With The Lion King, he was bound by set and costume requirements, as well as by the story itself. “I couldn’t go off in a wonderful field of abstraction,” he said. “I had to stay right there and tell the Lion King story.” For all the exposure that a choreographer can receive with a bigger venue and a high-profile project, the trade-off is the relinquishing of total control and a singular vision.

A significant and often-overlooked component of musical theater dance is tap, which has a long and rich history on the Broadway stage, as dance critic Brian Seibert writes in his Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive essay on the history of tap at the Pillow. Though, as Seibert points out, tap would only find a supportive home at the Pillow after Ted Shawn’s death, ever since the late 1970s it has been increasingly visible here and has become another example of the dialogue between the concert dance stage and Broadway.

The tap legend Gregory Hines made his one and only Pillow appearance in 1996, a few years after winning a Tony Award for his performance in the Broadway musical Jelly’s Last Jam. (Hines had been performing on Broadway since the 1950s.) In that production, the younger version of Hines’s character was played by a tap wunderkind by the name of Savion Glover, who had made his own Broadway debut several years earlier, at the age of 11. In 1996, Glover created the Tony-winning Broadway phenomenon Bring in Da’ Noise, Bring in Da’ Funk, and would finally come to the Pillow in 2002 with a solo performance. For a festival just warming up to tap, the Broadway credentials of Hines and Glover helped pave the way to a Pillow embrace.

Beginning in 1989, the post-modern choreographer Bill T. Jones began making regular appearances at the Pillow—a dozen to date. He has become one of the most prominent American dance-makers of his generation and known for furthering a compelling mix of lyrical dance with spoken text in his work—sometimes straightforward, sometimes poetic.

That interest in weaving words and movement has been an ingredient in his success bridging concert dance and commercial theater as the choreographer behind the 2007 Broadway production Spring Awakening and 2010’s Fela! He won Tony Awards for both.

This mix of projects, venues, styles and audiences inspired choreographer Sonya Tayeh to proclaim, in a New York Times profile by Pillow scholar Brian Schaefer, that she wanted a career like Jones.

She is on her way: After making her Pillow debut in 2018, she made her Broadway debut in the summer of 2019 as the choreographer of the stage adaptation of the movie musical Moulin Rouge! and was about to notch a second Broadway credit in the spring of 2020 with Sing Street before the Covid pandemic postponed that show’s premiere.

Tayeh is in good company as a new generation of choreographers mix and match opportunities to make work for commercial productions and for their own projects and companies. In 2018, Faye Driscoll returned to the Pillow with Thank You For Coming: Play, the second part of a three-part project. The work fused elements of straight theater with evocative gestures and outrageous physicality, which Driscoll put to use that same summer on Broadway in a cheeky dance scene for the play Straight White Men.

“My experiences in theater have really guided the way I tell stories because in theater, it’s all about the story.”Another of their contemporaries, Camille A. Brown, has long worked at the intersection of musical theater and concert dance. In a 2017 PillowTalk with Schaefer, she shared that she had grown up in a musical-loving home with Broadway cast recordings constantly in the air. The sensibility of musicals made sense to her, and that fusion of character and choreography is something that has been integral to her own work. “My experiences in theater have really guided the way I tell stories because in theater, it’s all about the story.”

She then applied it to the work she brought to the Pillow in 2017, Black Girl: Linguistic Play, a poignant portrait of Black female adolescence told in part through the language of childhood games. “In this case I wanted it to be about the story and how does this evolve and how do you see teenagers evolve into women?” Brown’s choreography has been seen at the influential off-Broadway Public Theater and on Broadway in the Tony Award-winning revival of Once on This Island and in Choir Boy.

Conclusion

The conversation between Broadway and Becket has been a consistent one driven by the artists who are interested in telling a story through movement—unafraid of, or even drawn to, the inclusion of dialogue and song—regardless of the stage it ends up on. For most of its existence, Jacob’s Pillow has hosted dancers who see dance as serving multiple purposes—sometimes as a vessel for emotion, sometimes as a way to challenge social conventions, and sometimes simply as a tool for entertainment. Broadway and modern dance audiences may expect different things from choreography, but those audiences are not mutually exclusive.

There are many of us who love both. And there are many choreographers who see no difference in the worth of a dance seen on a midtown commercial stage and one seen in a downtown nonprofit venue. It’s the power of the movement that matters. Legends like Jack Cole, Agnes de Mille, Jerome Robbins, and Bob Fosse demonstrated this maxim in the early and middle 20th century. Toward the end of the century, that baton was passed to dancemakers like Twyla Tharp, Garth Fagan, Savion Glover, and Bill T. Jones. In this century, choreographers like Camille A. Brown, Sonya Tayeh, and Faye Driscoll are taking a cue from these trailblazers to fashion careers that see every venue as a valid one, as long as their work is put to good use in the service of a good story.

And throughout, the School at Jacob’s Pillow has maintained a commitment to preparing young dancers for opportunities in musical theater, bringing in some of the industry’s top choreographers to help them become triple threats as actors, singers and, above all, dancers. In 2014, the Tony Award-winning choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler worked with students from the School at Jacob’s Pillow, teaching them a routine from a soon-to-premiere new musical about America’s founding fathers that they performed on Inside/Out and in a special presentation called A Jazz Happening. That’s right: Pillow audiences got a glimpse of Hamilton a year before it came to Broadway and became an international phenomenon. What better illustration is there of the deep bond between Broadway and Jacob’s Pillow?